CINCINNATI — The Ohio Lesbian Archives in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood started with a friendship.

Phebe Beiser said that when she and co-founder Victoria “Vic” Ramstetter met in the 1970s, they bonded over being “hidden, secret, teenage lesbians,” growing up in what was then a conservative city and region where there were few gay role models. For a time in their 20s, they shared group houses in Clifton, where they now joke that they “survived the lesbian commune together.” They were young and idealistic. They wanted to “turn being an activist lesbian into something fun and interesting, and maybe help change the world.” Beiser, now in her mid 70s, told The 19th that they had a mantra: “We never wanted to be invisible again.”

When the Crazy Ladies Bookstore, named for the women who history brushed off as “crazy,” opened in Northside in 1979, it became the center of gravity in the Cincinnati lesbian community of which Beiser and Ramstetter were a part. Women bought homes in the neighborhood, gathering at the feminist bookstore for coffee, tea and conversation about being women, and about being gay. In 1989, the Archives opened on an upper floor.

It seemed that the visibility of the Crazy Ladies Bookstore and the Ohio Lesbian Archives — and of the women who made them happen — would be cemented in history in 2023, when the Ohio History Connection, the state’s nonprofit historical society, “embarked on a three-year project to diversify Ohio’s historical markers to include ten new stories of LGBTQ+ Ohioans” via its Gay Ohio History Initiative, or GOHI. At the time, there were roughly 1,800 historical markers in Ohio’s program, but only two commemorated places, events or people from the state’s queer history. A third, recognizing Summit Station, a lesbian bar in Columbus that operated from 1970 to 2008, was dedicated during Pride Month that year. The Archives and bookstore were selected for joint recognition.

That long-overdue acknowledgement has been derailed by the Trump administration’s sweeping war on DEI, which extends beyond diversity, equity and inclusion programs to seemingly include anything that acknowledges the country’s diversity of experience. But the archives — and the volunteers who sustain it — are undeterred, carrying on as the queer community has throughout history, documenting their existence.

We never wanted to be invisible again.”

Phebe Beiser

The Marking Diverse Ohio program was financed by a $250,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, an independent agency created by a Republican-led Congress in 1996 that is the main source of federal funding for libraries and museums. Beiser and Branstetter were interviewed for an oral history. Ohio History Connection researchers visited the Archives to peruse the collection. A location was secured in a city park near where the since-shuttered Crazy Ladies Bookstore once was. By early this year, preparations to forever commemorate the Archives and bookstore with a plaque were all but complete. Its installation was expected in June, Pride Month.

Then, in late March, President Donald Trump issued an executive order regarding “The Continuing Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy,” singling out seven agencies for elimination — including the Institute of Museum and Library Services, or IMLS. Nearly all of its employees were put on leave and their emails were disconnected. Days later, his administration’s Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, canceled $25 million worth of already-awarded IMLS grants, including the $250,000 for Ohio History Connection’s Marking Diverse Ohio program. The federal agency’s seemingly final Instagram post stated: “The era of using your taxpayer dollars to fund DEI grants is OVER.” The last photo listed erecting “LGBTQIA+ historical markers across Ohio” among the alleged government excesses that would be cut.

-

Read Next:

Svetlana Harlan, a former project coordinator for Marking Diverse Ohio, recalled that when she looked at the list, and saw the program with other projects she admired, “it almost seemed like a positive thing, I was like, ‘Oh yeah, these are nice initiatives!’”

“And it turns out that [DOGE] was just taking over the account. So then I was like, ‘Oh, they’re cutting those. Oh, our name is on the list,’” she said.

DOGE’s cancellation of the $250,000 IMLS grant to Ohio History Connection threw into question the future of the markers that were supposed to ensure that Ohio’s public displays of its history include LGBTQ+ people. Along with the Ohio Lesbian Archives and the Crazy Ladies Bookstore, there were markers in the works for an LGBTQ+ district in Akron; the first professor of gay and lesbian studies at Kent State University; 19th-century sculptor Edmonia “Wildfire” Lewis; LGBTQ+ journalism in Ohio; Toledo’s first LGBTQ+ member of city council; a Columbus hospice care center for HIV and AIDS patients; an open lesbian pastor in Athens; the screen-printing company Nightsweats and T-Cells in Lakewood; and the Rubi Girls, a Dayton-area drag group that has raised more than $3 million for HIV/AIDS and LGBTQ+ causes since the 1980s.

(Courtesy Ohio Lesbian Archives)

Preservation on hold

Marking Diverse Ohio and other programs recognizing specific communities weren’t the only programs impacted in the state when DOGE cut IMLS grants and the federal agency essentially shuttered. And, given that more than $250 million is granted annually to libraries and museums nationally, the economic chaos at the country’s museums, libraries and historical institutions wasn’t confined to Ohio.

In Ohio, other entities that received recent IMLS funding include the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Westcott House in Springfield, for post-pandemic, on-site programming; the Cincinnati Zoo for a big cat breeding program; Dayton Metro Library programs that helped low-income Ohioans secure Internet access; and Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center, which lost $175,000 slated for programming aimed at the 3,000 or more teens it serves each year.

Institutions in Pennsylvania warned the economic upheaval could scuttle the digitization of The Rosenbach museum’s collection of rare books and manuscripts; the Woodmere Art Museum was mid renovation on a building to house its collection and expected to be reimbursed. In Wisconsin, small-town libraries said without the $3 million from the IMLS they’d received the year before they would have to reduce staff and therefore services. The American Library Association, or ALA, and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, the labor union representing government workers, sued the Trump administration. ALA President Cindy Hohl said at the time that, “Libraries play an important role in our democracy, from preserving history to … offering access to a variety of perspectives.” AFSCME President Lee Saunders added: “Libraries and museums contain our collective history and knowledge.”

Earlier this month, a federal judge ruled that the Trump administration could continue dismantling the Institute of Museum and Library Services as the case continues.

-

Read Next:

For now, Ohioans who want LGBTQ+ history represented among the 1,800 markers in the state will not get the federal funding that was granted and must search for alternative resources in their communities. A couple of the markers look poised to move forward with outside funding from community foundations and other organizations. Others, like the Ohio Lesbian Archives and the Crazy Ladies Bookstore, are still waiting. The remaining cost to install the marker would likely be $3,000-$5,000.

When The 19th reached out to Ohio History Connection to ask if any alternative funding sources were being explored to install the Archives’ marker, spokesperson Neil Thompson said that he was “not able to provide any additional information for an Ohio Historical Marker application that is not in the public domain” and that it is only considered in the public domain once “the markers are finalized, cast and ready to be installed and dedicated.”

‘A reflection of themselves’

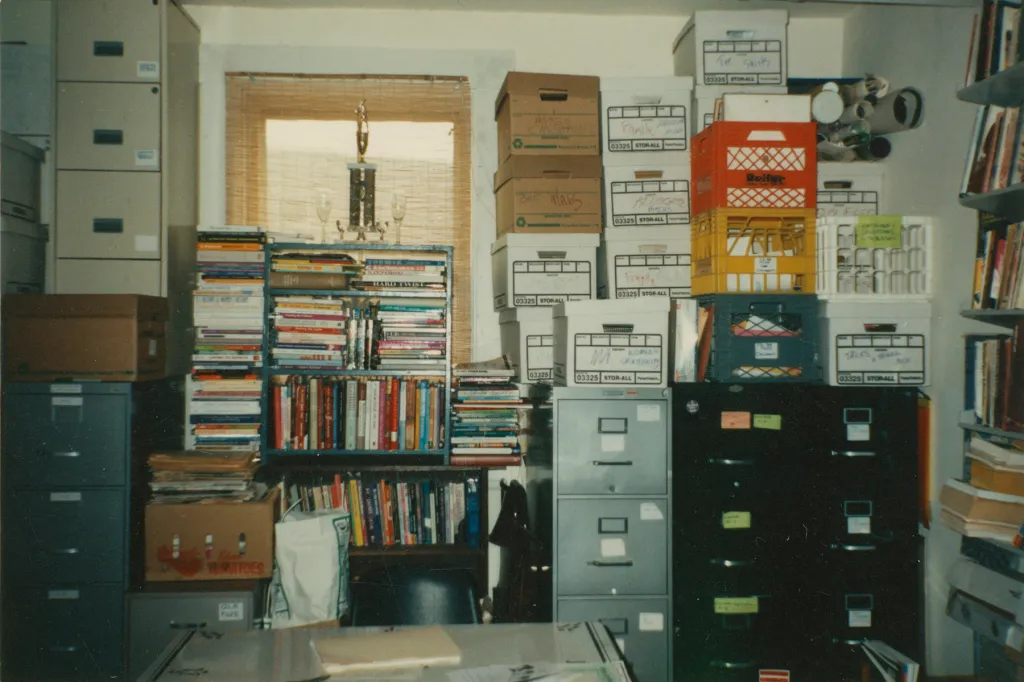

The Ohio Lesbian Archives has always been a DIY endeavor, powered by a group of passionate volunteers.

When the Crazy Ladies Bookstore’s founder, Carolyn Dellenbach, moved out of the area, she handed it over to its patrons to be run as a feminist collective. A lesbian newsletter called Dinah operated out of the upper floor — they referred to the National Organization for Women’s Task Force on Sexuality and Lesbianism, established in 1973, as FOSAL, or fossil, and Dinah was a play on dinosaur. Beiser laughed explaining the name: It was the 1970s; maybe there were drugs involved. For a time she wrote for Dinah and loved interviewing famous arrivals from the “women’s music circuit” when they came to town.

At some point, the women working shifts at the bookstore, writing for Dinah and organizing talks and other events related to feminist and lesbian issues, realized that the community they had built, and the ephemera they were collecting and creating, were an important part of history — theirs, lesbians,’ Ohioans,’ and women’s.

“We held on to them because we knew they could not be replaced,” Beiser said of the collection. “It’s proof of our existence … so we held on to these things to never be invisible again.”

We held on to them because we knew they could not be replaced. It’s proof of our existence.”

Phebe Beiser

In a 1991 issue of Dinah, letters to the editor included one from “Ma” who updated the “wimmin” in the community — they often spelled variations of their gender in ways that did not include “man” — that she was homesteading outside the city with her partner and building a log cabin. Another was from a woman who said she was “shocked” to find out that her being fired for being a lesbian was not a violation of civil rights laws and she was disappointed that the LGBTQ+ community did not come out to support her recent picket, writing: “I hope that in my lifetime I will see the gay and lesbian community get off their asses and together start fighting for their rights.”

Across from the metal filing cabinet at the Archives that houses the Dinah issues, a modern-looking poster from before the Supreme Court decided Bostock v. Clayton County in 2020, which extended employment protections to LGBTQ+ Americans, reminded Ohioans that it was still legal for them to be fired for their sexual orientation or gender identity. Today, Trump’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is aiming to curtail those hard-won workplace protections established by Bostock.

Lüdi Rich, a 27-year-old librarian, was working a recent Sunday afternoon at the Archives’ twice-weekly open hours, organizing books and research materials while the space was open to members of the community to drop in.

-

Read Next:

When Rich moved to Cincinnati nearly two years ago, she didn’t know anyone in the area, so she looked online for queer spaces so she could start building her community. When she attended a panel on local queer history, one of the speakers was Beiser, a longtime librarian herself in the country’s second-largest public library system.

Beiser mentioned at the panel that the Ohio Lesbian Archives would be having an open house that night at its new location next to Over-the-Rhine’s Washington Square Park, where Beiser was among those who met to march in Cincinnati’s first Pride Parade in April 1973. Rich asked Beiser how she could volunteer.

A couple months later, Rich showed up for her first shift, “And I’ve been here working ever since,” she said.

Nancy Yerian, the 34-year-old president of the Archives’ board, said that when she graduated from college in Massachusetts, she didn’t know if she could return to Cincinnati, where she grew up — until she discovered the Archives. “I thought that to live the kind of life I wanted to lead, I had to get out of what I thought was a very conservative place,” said Yerian, who has been volunteering at the Archives in some capacity since shortly after she finished school.

“Finding the Archives and the people I’ve met through the organization and the community we’re creating, as well as the history we’re preserving — it gave me a lot of hope that I could create a life for myself here,” she added.

It really is just us, preserving our history.”

Lüdi Rich

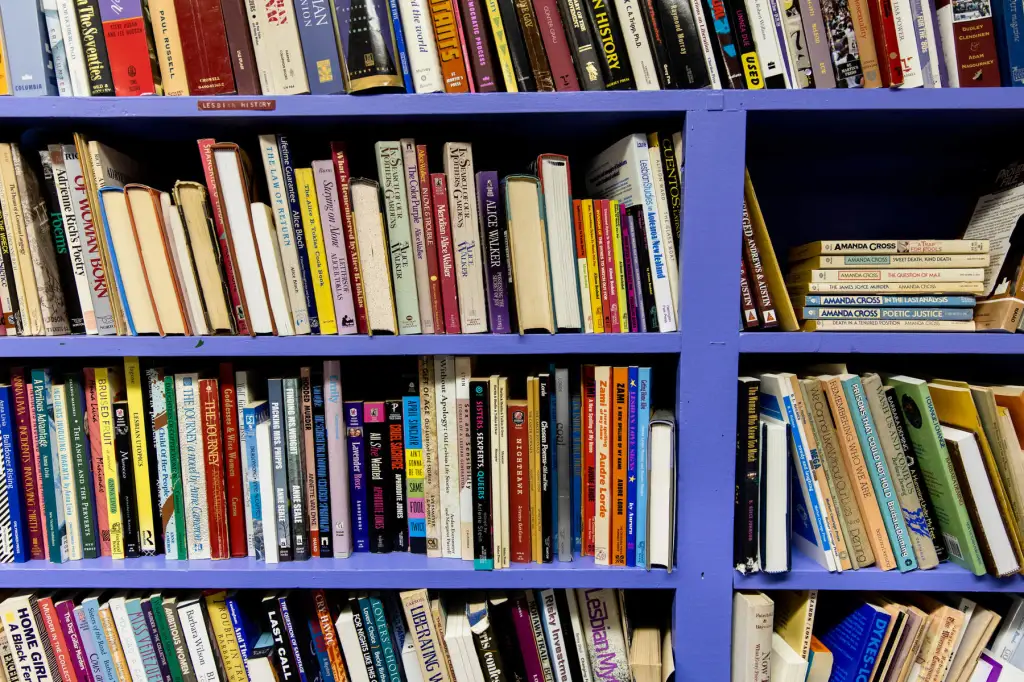

The Archives’ volunteers have helped digitize old photos, some of which are now in a collection at the Cincinnati Public Library. They organize the books, arranged by first names instead of last, since so many women, especially in those early years, published works after taking on their husbands’ surnames. There are filing folders of Dinah newsletters. A cabinet holds multiple VHS and DVD copies of the early aughts television drama “The L Word.” A collection of buttons includes those from past Pride marches; supporting Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaigns; and one with “REMEMBER” and an inverted pink triangle, the Nazi symbol that Adolf Hitler used to identify gay and trans people. There is also one with the logo of the Crazy Ladies Bookstore, the silhouette of a woman reading while reclined in a chair, a cat by her side.

“Many people who are coming to the archives are looking for a reflection of themselves and in many ways that’s why Vic and Phebe started it. It shows models of ways to be in the world and a feeling of not being alone and not being the first queer person or lesbian,” Yerian said.

The Ohio Lesbian Archives, marker or not, is and will keep doing what it always has: making sure that lesbian Americans are visible in the country’s historical record.

“It really is just us, preserving our history,” Rich said.

Feeling overwhelmed by the news? The 19th is considering new ways to keep you informed. But we need your input! Fill out this quick survey to share your thoughts.