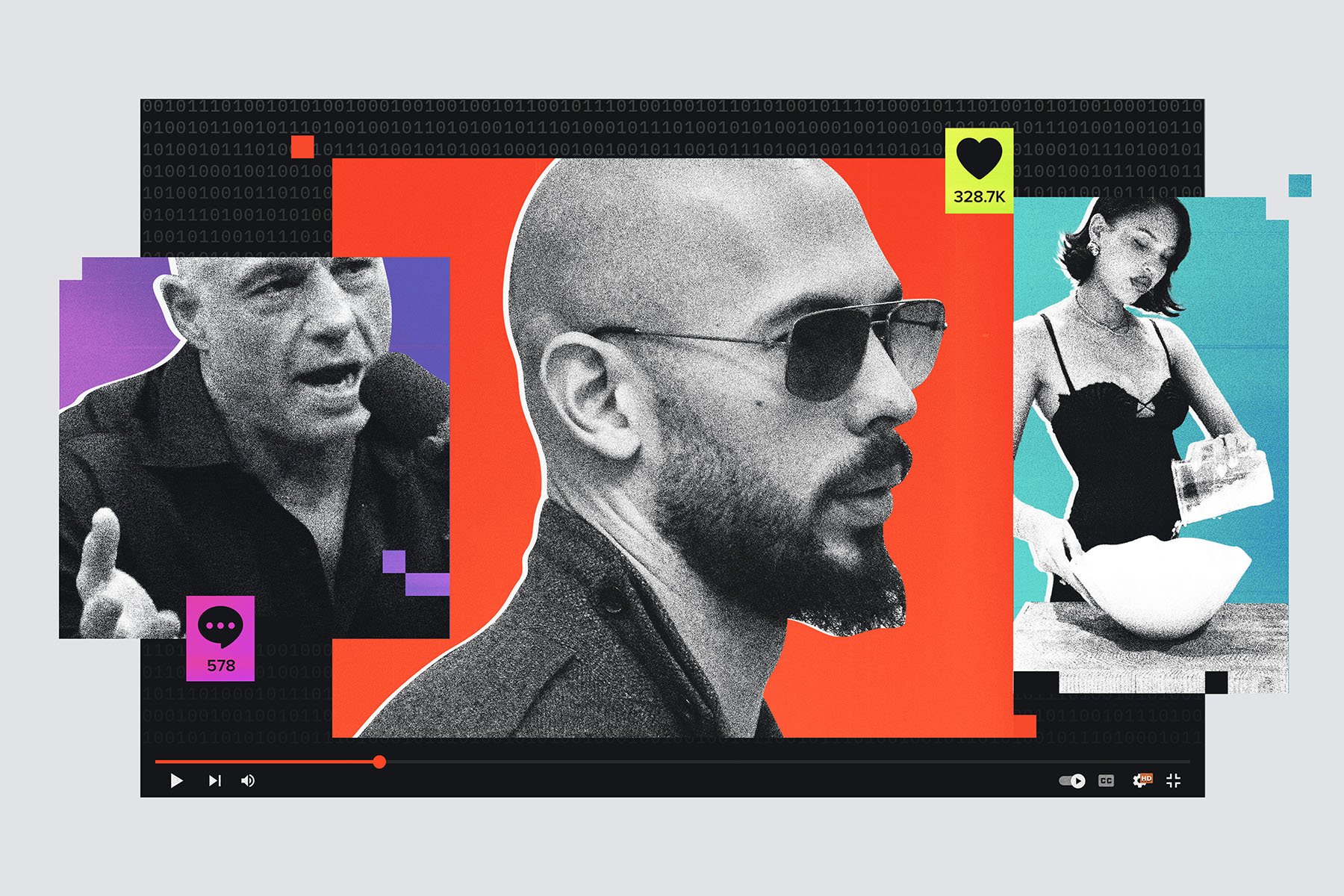

Aarush Santoshi struggled for words when a preteen boy approached him on a New Jersey street, shoved a phone in his face and asked: “What are your thoughts on Andrew Tate?”

The kid’s smirk and the fact he was recording rattled Santoshi, a high school junior at the time. Santoshi worried that the tween viewed Tate — an influencer accused of sexual assault and trafficking — as a joke to spring on strangers.

“This kid was engaging with content that promotes blatant misogyny, and he didn’t even realize how harmful it was,” said Santoshi, now 18 and the national political director of Feminist Generation, a youth-led organization that opposes authoritarianism. The encounter was a chilling sign of how deeply the “manosphere” — a network of online influencers promoting male supremacy and far-right ideologies — had infiltrated popular culture.

The manosphere and parallel trends like the tradwife (traditional wife) movement — led by influencers who idealize marriage, motherhood and domesticity — are impacting even socially conscious students who say it’s hard to avoid this content brimming with toxic messages about gender. Over a half-dozen students told The 19th that after the 2024 election, which saw the manosphere blamed for young men’s rightward shift, they noticed changes in their classmates’ behavior — an uptick in sexist remarks, a sense of entitlement to girls’ attention and schadenfreude that yet another woman lost the presidency.

Now, educators, parents and advocates are racing to counter the manosphere’s influence by addressing online gender dynamics with students — while youth themselves are pushing back through activism, their studies and debates with their peers.

Santoshi’s introduction to the manosphere came via YouTube. Fifty-two percent of young men ages 18 to 23 are on that platform, according to 2023 report “The State of American Men” by the nonprofit Equimundo: Center for Masculinities and Social Justice. In eighth grade, Santoshi discovered YouTube’s Jubilee channel, which presents discussions between people with opposing political views.

“One of the topics was men’s rights activists versus feminists, and one person on the men’s rights activist side was a self-proclaimed incel,” Santoshi said, referring to the term used by men who resent being “involuntarily celibate” — many of whom have connected with likeminded individuals on platforms like Reddit. “He was saying all these objectively horrendous, terrible things about women, very infantilizing, very paternalistic.”

-

Read Next:

-

Read Next: The state of American men is — not so good

The manosphere — which dates back to the Y2K era, when anti-feminist men began to gather online — includes incels and men’s rights activists who feel disadvantaged by women’s social progress. Also involved are men going their own way (known by MGTOW), who have sworn off relationships with women; and pick-up artists who manipulate women into sex. The Equimundo report found that nearly half of young men trust at least one manosphere influencer. They have swallowed the “red pill” — a manosphere metaphor for embracing a reactionary and male supremacist worldview.

“Similar to white supremacy, male supremacy can be an extremist ideology or movement in and of itself, but it’s also sort of embedded in American society,” said Rachael Fugardi, a senior research analyst with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, which tracks extremism.

An outgrowth of male supremacy, the manosphere’s dangers are too often downplayed, said Santoshi, who credited growing up in an egalitarian household with preventing influencers from enthralling him. Recently, his philosophy class at Stanford University discussed the toxic masculinity of Elliot Rodger, an incel who died by suicide after his 2014 rampage near the University of California, Santa Barbara, left six people dead and 14 injured.

“People think it’s just these influencers who are trying to sell patriarchy to young men,” Santoshi said of the manosphere. “Elliot Rodger was a case study for what happens when male entitlement, white supremacy and these different entitlement ideologies combine and actually result in political violence.”

The gateway drug to the manosphere: algorithms

The vast majority of young men stumble onto the manosphere through innocent online queries, and algorithms set the trap, explained Geoff Corey, director of Advocates for Youth’s sex education project AMAZE.

“They are looking to make friends, to look better, to win over girls or become better people,” Corey said. “Then, they discover that it seems like the only people creating content geared towards men are people who give them an easy answer for what they want, and that easy answer somehow leads to trickery, violence, unhealthy behaviors, bottling up emotions.”

A teen might watch “gym-bro” motivational content or videos on “looksmaxxing” to enhance his appearance, only to be steered toward posts about the pitfalls of being a weak “beta male” instead of a dominant “alpha male.” Before long, the algorithm offers more of the same, ensnaring him in the manosphere’s quagmire. Social isolation makes youth more likely to get bogged down, according to Equimundo’s report. It found 65 percent of young men say no one knows them well.

Fugardi said that algorithms force-feed sexism to young people. “So much of this misogynistic content isn’t being searched out,” she said. Research from the United Kingdom revealed that 10 percent of boys ages 11 to 14 encountered harmful content, such as misogyny and violence, within 60 seconds of going online.

More than a particular political ideology, boys and young men are drawn to humor online, according to Corey. Comedic content creators may not peddle toxic rhetoric initially but simply behave in boneheaded ways that rack up page views. They go on to promote everything from extreme diets to polarizing politics.

Sam Dyer, a recent graduate of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, pointed to the viral fitness influencer Togi, a beefcake who recorded himself slapping a woman’s backside in one video and insulting WNBA fans in another. Dyer served as the fraternity caucus chair for It’s On Us, a nonprofit that fights campus sexual assault in stark contrast to the manosphere’s rape culture.

Togi’s content, which routinely mentions steroids and betting, is largely humorous, Dyer said, but that doesn’t mean the influencer’s fans view him as a joke. “He just constantly records his lifestyle, which seems to be a lot of drugs and a lot of gambling and drinking and working out,” Dyer said. Given the Pew Research Center’s finding that 43 percent of teenage boys feel pressure to be physically strong, it’s no mystery why fitness influencers resonate with them.

As a fan of the Ultimate Fighting Championship, which promotes mixed martial arts matches, Dyer is also familiar with Joe Rogan, a former commentator for the sport. Now host of “The Joe Rogan Experience,” the podcaster is linked to the manosphere because he leans into gender essentialism and conspiracy theories, a focus of the movement. Rogan welcomed Donald Trump to his show in October but reportedly refused to make arrangements for Kamala Harris to appear, going on to endorse Trump for president.

Arguably no manosphere leader is as polarizing as Tate, whose prominence on social media has made him hard to ignore, Dyer said. More young men ages 18 to 23 (20 percent) trust Tate than rival manosphere figures like Rogan and Jordan Peterson, a Canadian psychologist, according to the Equimundo report. The often shirtless influencer’s misogynistic posts — referring to childfree women as “miserable stupid bitches” and suggesting that women must “take some degree of responsibility” to avert rape — have seen him banned on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram. Still, his content has spread like butter, finding fans in young viewers like the president’s son Barron Trump.

Tate emerged as a manosphere leader, Dyer contends, because his social media posts appealed to broad audiences. “He would gamble, he did kickboxing, so there were a variety of ways that he could interact with various people’s internet feeds,” Dyer said. “That became a way for people to get exposed to his more radical ideologies, especially towards women.”

Performance art or propaganda: the impact of tradwives

Just as young men wrestle with the manosphere, young women are confronted with male supremacy through the tradwife trend.

Tradwife influencers like Nara Smith, who films herself cooking in expertly applied makeup and flawlessly coiffed hair, insist they’re simply sharing their passion for homemaking. Many of Smith’s followers regard her content as performance art. Her meal-prep wardrobe features dreamy blues and cherry reds in sequins, chiffon and faux fur — all while she whips up snacks like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, bread included, entirely from scratch.

Tradwife critics, meanwhile, argue that influencers like Smith, Hannah Neeleman and Estee Williams are anti-feminist since marrying young and having gaggles of children appear to be prerequisites to the lifestyle.

“Male supremacy appeals to women as well. And, of course, the white supremacist project demands the participation of White women in the production of White babies,” said Pasha Dashtgard, director of research at the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University. The tradwife movement “is for men,” he stressed. “It’s not for women. It’s cosplaying what men think would be the ideal woman.”

Tradwife and manosphere influencers communicate that marriage and children aren’t optional, according to their detractors and some of their impressionable teen viewers.

“The manosphere — I think that is just such nonsense,” said Sreshta Erravelli, 17, who recently finished 11th grade in New Albany, Ohio. “I can speak for so many girls I’ve talked to that it is really promoting just the worst culture ever for so many guys. Then, when you couple that with the whole tradwives trend, it’s definitely hard to reconcile both things at the same time.”

Boys learn to be rugged alpha males from the manosphere, while girls learn to cater to men from tradwives, Erravelli has observed. Rather than teach that rejection is a part of life, the manosphere links rejection to weakness, causing boys to lash out when girls don’t reciprocate their feelings, she said. “You’re calling girls weird names just because she didn’t give you her number the first 20 times you asked.”

-

Read Next:

During the rollout to the 2024 election, the gender divide among Erravelli’s classmates became clear. Some of them argued that a woman shouldn’t be president, an attitude that reflects the manosphere’s chauvinism.

“When it came down to kids who were in favor of Trump, I think that they were definitely a little too gleeful about the fact that it was a man winning over a woman, which is just so weird to say in 2025,” she said. “It was just a conversation of, ‘Why are you so happy that a woman lost?’”

While the manosphere elicits discomfort, she and her friends joke about Nara Smith whenever they cook. Threaded through their humor, though, is uncertainty concerning what tradwives signify about women’s roles in society.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, you don’t know how to make your own butter at home. How are you gonna run a house?’” Erravelli said. “It’s kind of funny to look at this all from the perspective of a teenage girl. You get told not everything you see on the internet is real, and that’s true. But when you see that these ‘trends’ are just totally affecting everyone you know, it’s kind of hard to believe that they’re not.”

The teacher helping students counter the internet’s gender cues

Some educators like Jessica Berg are helping students navigate toxic internet culture. Her gender studies class at Rock Ridge High School in Virginia covers everything from ancient civilizations to the present-day backlash against feminism to help students understand how patriarchy became the norm. As part of the course, students learn about digital misogyny and the tradwife trend.

Berg launched the course after the 2016 election, when students kept asking her why Hillary Clinton, widely considered one of the most qualified presidential candidates in history, lost the race to a man who had never held public office. Since then, she’s seen a resurgence of sexism. Fifty-five percent of young men agree that “men have it harder than women” and just under half agree that feminism has bettered the nation, the Equimundo report found. Berg suspects the manosphere bears some responsibility for misogyny’s growth. After the 2024 election, far-right influencer Nick Fuentes’ post mocking women’s reproductive rights — “Your body, my choice” — spread among students. “Young males were texting that, DMing it, posting it to young women,” Berg said.

Her class teaches students, mostly girls, to challenge sexist messaging. Blessing Amuga, one of her students, confronted a male acquaintance who claimed women were “too emotional” to be president. “That doesn’t even make sense,” Amuga said of that sexist stereotype. She went on to point out how Trump, who has lost his cool in office on multiple occasions, supports policies that are actively harmful to women, including controlling women’s bodies. His policies reinforce “the idea that men should control what you do, what you eat, how you act,” Amuga told him.

Her classmate Isabella Hasbun noticed boys parroting Trump’s insults toward Kamala Harris, mirroring the manosphere’s misogyny. “Them seeing a White man calling a Black woman dumb and saying that she has no qualifications just enhances their own [preconceived] thoughts,” said Hasbun, a recent Rock Ridge graduate, like Amuga.

-

Read Next:

-

Read Next: Classrooms are dominating the culture war

Hasbun has seen more tradwives on her TikTok feed than manosphere influencers. She questions anyone who suggests she should spend her time cooking at home. Of them, she wonders: “What are you doing with your life?”

Rianna Abdelhamid, who also took Berg’s class, said domestic life is fine for women who enjoy it. “But not everybody is like that,” she said. To those expecting her to be a tradwife, she offered three words: “No, thank you.”

It’s the manosphere, though, that Hasbun objects to most. “That is the worst type of man you will ever find,” she said of the trend’s followers. Post-election, she’s faced repeated harassment from boys, she said, recalling a group of them circling the car she and a friend were in at a drive-thru — “thinking that they had the privilege of actually talking to us.”

Being in Berg’s class has empowered Hasbun and her classmates to advocate for women, and, in turn, themselves. Abdelhamid now speaks up instead of staying silent when she’s concerned about sexism. Hasbun has grown more confident. When she has a disagreement related to gender, she trusts her perspective: “I’m well aware of what’s actually happening instead of just basing my opinion on what some random dude on TikTok said.”

Is there an antidote to the red pill?

Influenced by social media, young people may not only slip into the manosphere but become radicalized to the point of performing extremist acts. As research director at PERIL, Dashtgard designs tools, guides and resources to obstruct that pipeline using a public health approach.

“We work with all levels of civil society — teachers, parents, faith leaders, small business owners, any kind of trusted adult in the life of a child,” Dashtgard said. “We want to help understand the nature of radicalization and what they can do in order to disrupt that.”

PERIL, in partnership with the Southern Poverty Law Center, released a guide last year called “Not Just a Joke.” The goal, Dashtgard said, is to arm the public with the knowledge needed to recognize radicalization before it occurs and engage youth without condemning or humiliating them. These resources, if distributed, can become a preventative model scalable in communities nationally.

Fugardi, of the SPLC’s Intelligence Project, said social media platforms could provide another avenue for solutions.

“We should be looking for social media companies to do more as they’ve grown in influence in our society,” she said. “We should have high expectations for them to not just enforce their own rules [around content moderation], but also to release transparency reports about how they’re protecting young people over prioritizing profit.”

-

Read Next:

The AMAZE project, which posts animated sex ed videos to YouTube and other platforms, presents youth with alternatives to the manosphere’s messaging about manhood — including its framing of issues like relationships and sexuality. Through Equimundo’s Link Up Lab — a hub that allows organizations to test different digital strategies to provide young men with healthy ways to pursue belonging — AMAZE consults with youth on the materials it develops for the web.

“We have videos on the stuff that a sex educator might cover in class, but we also try to answer a question that a young person is really searching for,” Corey said. “One of our most popular videos is ‘Does Penis Size Matter?’ That is not going to be in the health education curriculum, but it is what someone is searching for, and we create animated, funny content about that.” In the fall, AMAZE plans to release a video on looksmaxxing, a dangerous trend linked to steroid use and do-it-yourself body modification that feeds off teen boys’ insecurities about their physiques, jawlines and even their hair.

Julie Scelfo, founder of the grassroots group Mothers Against Media Addiction, urges caregivers to co-view content with kids. Check their browser history, and if they repeat sexist ideas, ask where they heard them.

“If your kid is exposed to Andrew Tate-type influencers, it’s critical to have conversations about who he is and what you think about the messages that he’s espousing,” she said.

Early discussions about toxic content are key. Once youth enter college, they’ve already absorbed gender constructs, Corey said.

“AMAZE is unique in the sex ed space in that we offer health education, relationship education, puberty education that is targeted towards adolescents because we think that’s when they actually start developing their opinions and their views on the world.”

So, for that kid who confronted Aarush Santoshi, there’s still time. Parents have more sway than influencers, Corey contends — if they act before harmful ideologies take root.

Feeling overwhelmed by the news? The 19th is considering new ways to keep you informed. But we need your input! Fill out this quick survey to share your thoughts.