In 2019, Cristina Iglesias filed a lawsuit that changed the course of treatment for herself and other transgender inmates in federal custody.

Iglesias, a trans woman who had been incarcerated for more than 25 years, was transferred from a men’s prison to a women’s one in 2021. And in 2022, she reached a landmark settlement with the Federal Bureau of Prisons to receive gender-affirming surgery, which the agency said it had never provided for anyone in its custody.

By the time she got the surgery 10 months later, another federal inmate had also received a procedure to align their body with their gender identity. No other such surgeries for people in federal custody are publicly documented, although some people in state prisons have also received gender-affirming surgery, including at least five in Illinois and 20 in California within a U.S. prison population that tops 1.25 million people.

Still, those procedures loomed large in the 2024 presidential election. Political advertising for President Donald Trump and other Republicans included $215 million on anti-trans ads, according to media tracking firm AdImpact. One such ad declared that Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris supported “taxpayer-funded sex changes for prisoners,” and concluded, “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you.” Some Democrats bemoaned the ads as having helped tip the election.

In the run-up to the November 5 election, 55 percent of voters felt support for trans rights had gone too far, according to VoteCast, a survey by The Associated Press and partners including KFF, the health policy research, polling and news organization that includes KFF Health News.

On Inauguration Day, Trump issued a flurry of executive orders that included a directive to bar federal spending on gender-affirming care in federal prisons and to “ensure that males are not detained” in federal women’s facilities.

“President Trump received an overwhelming mandate from the American people to restore commonsense principles and safeguard women’s spaces — even prisons — from biological men,” White House spokesperson Anna Kelly wrote in an email. “Forcing taxpayers to pay for gender transition for prisoners is the exact sort of insanity that the American people rejected at the ballot box in November.”

But for Iglesias, 50, Trump’s order was a shocking reversal.

“It puts someone’s life in danger being in a men’s prison as a trans woman,” she said from Chicago, where she’s lived since her release in 2023. “It’d be like putting sheep in a hyenas’ den.”

-

Read Next:

Iglesias said she faced emotional and physical abuse from her father for her desire to be female. When she was 12, she said, he put a gun in her mouth after finding her wearing her sister’s clothes. Iglesias said she ran away from home, stole checks, cars and jewelry, and ended up in jail.

Lockup was not fun, Iglesias said, but it was the first place she got to be treated as a woman. So, she said, she wanted to stay. In 1994, she landed in federal prison after writing threatening letters to federal judges and prosecutors, according to court filings. In 2005, records show, she pleaded guilty to sending a letter to British officials that she falsely claimed contained anthrax. She told investigators she hoped to get extradited.

“I was reading these things where they were allowing trans females to start living with females,” Iglesias said.

She said her outlook changed after the death of her mother in 2010, which prompted her to get serious about having a life outside of prison, and about improving her life inside it.

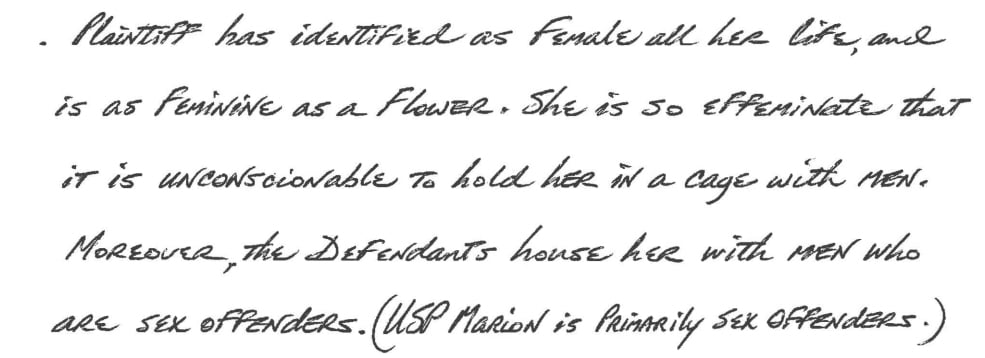

She began requesting hormone therapy in 2011 and was approved for it in 2015, according to court records. The 2019 lawsuit that led to her transfer to a women’s prison and her surgery was initially handwritten and prepared with the help of only another inmate.

“The lawsuit was the foundation for everything that I am today,” Iglesias said. “For the first time in my life, instead of digging myself in these holes, I was digging myself out.”

Along with her settlement, Iglesias received a commitment from the Federal Bureau of Prisons to create a timeline for considering other inmates’ requests for gender-affirming care, and to recognize permanent hair removal and gender-affirming surgery as medically necessary treatments for gender dysphoria — a medical condition in which the discrepancy between a person’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth causes significant distress.

In February, in response to Trump’s executive order, the bureau issued new guidelines requiring prison staffers to refer to inmates’ “legal name or pronouns corresponding to their biological sex,” and ending clothing requests “that do not align with an inmate’s biological sex.” The guidelines end referrals for gender-affirming surgery but allow inmates already receiving treatment, such as hormone therapy, to continue.

However, in a lawsuit filed March 7, a trans prisoner alleged the hormone therapy she had been receiving since 2016 was stopped on January 26.

Spokespeople for the bureau did not respond to requests for comment.

The bureau spent $153,000 on hormone therapy in fiscal year 2022, its former director told Congress, 0.01 percent of its total spending on health care.

The new guidelines on trans inmates say that Trump’s executive order “does not supersede or change” the obligation to comply with federal regulations. But the executive order calls for amending them to prevent trans women from being housed in women’s prisons.

“It hurt my heart when I seen that because I do know other girls that are still in prison,” said Iglesias, who spent more than 25 years in male facilities. “Female prison is safe for a trans woman, and you can be who you are. You’re not penalized because you’re feminine.”

But requesting a transfer to a facility matching inmates’ gender identity had not been easy, and few prisoners had been moved before the order. A 2025 government court filing said that federal prisons house 2,198 trans prisoners out of over 155,000 inmates. Of those, the filing said, 22 are trans women housed in female facilities and one is a trans man in a men’s facility. Although courts have blocked attempts to move that small subset of trans prisoners after the order, The Guardian reported that a trans prisoner not included in those suits had been relocated.

A Department of Justice report from 2014 estimated that trans inmates in state and federal prisons were 10 times as likely as other prisoners to report incidents of sexual victimization.

Iglesias said she experienced such violence firsthand. Included in her suit was a copy of a 2017 psychological report that said Iglesias reported being the victim of sexual misconduct or abuse in 1993, 2001, 2013, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Later filings included allegations of having been raped in 2019 and 2020, and a series of rapes, threats and other abuse in 2021 before she was transferred to a female facility. Iglesias said she faced more abuse than she officially reported.

“Just because you commit a crime doesn’t mean you deserve to have violence against you,” said Michelle García, deputy legal director of the ACLU of Illinois and one of the attorneys who ultimately represented Iglesias.

Federal law requires all inmates to be protected from abuse. A 1994 Supreme Court decision acknowledged trans inmates as particularly vulnerable to attack. Regulations from the Prison Rape Elimination Act, passed unanimously by Congress in 2003, contain specific provisions for trans inmates, including allowing them to shower separately from other inmates and requiring prison officials to consider their health and safety when deciding whether to house them in male or female facilities.

Courts also have ruled that “deliberate indifference” to an inmate’s “serious medical needs” violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual” punishments. The quality of overall medical care for federal prisoners has come under scrutiny amid reports of inmates going without needed medical care and preventable deaths.

Iglesias successfully argued in court that gender-affirming surgery was necessary for her gender dysphoria. She was diagnosed with what was then called “gender identity disorder” soon after entering federal custody in 1994, according to court filings. Her diagnosis was updated to gender dysphoria in 2015.

Iglesias’ court filings documented her having been assessed for the risk of suicide 33 times and placed on suicide watch 12 times, as well as an attempt at self-castration in 2009.

“Defendants are aware of Iglesias’s suffering, but have delayed her treatment without evaluating her medically,” the judge in her case wrote.

García called the Trump administration’s targeting of care for trans inmates cruel, unnecessary, and illogical.

“They’re not assessing the constitutional rights of people,” García said. “They’re making choices because this is a vulnerable community that they can rally people behind to hate.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.