This story was published in partnership with LOOKOUT, a nonprofit news outlet focused on LGBTQ+ accountability journalism in Arizona. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Nova Galloway graduated from Grand Canyon University with one goal: become the kind of teacher students would not only be excited to learn from, but also feel safe enough to confide in.

Galloway, who lives in Tempe, a city neighboring Phoenix, said the first few years of teaching were manageable. But then the pandemic hit, and frustrations grew over the lack of resources provided to teachers, the little technology offered to students to learn from home, and backsliding on in-person schooling despite rising COVID numbers in the state. At the same time, the state legislature was passing stricter laws on how teachers could address student issues, particularly around sexuality and gender.

Teachers across the state — and the country — were starting to be called “groomers” by school board officials and parents for discussing sexual health issues, utilizing books with LGBTQ+ characters, or even teaching proper pronoun usage. In Arizona, one teacher had a rock thrown through a window at their home after a school board member posted their address, allegedly targeting them for being nonbinary, and another had death threats after her phone number was leaked by local far-right media because they lead a local group for parents of trans youth.

Galloway believed in keeping a low profile. But in the past few years, Galloway also began to recognize they didn’t feel comfortable with their sex assigned at birth. They started using different pronouns and a new name outside of school, which students caught wind of when they found Galloway’s TikTok account.

-

Read Next:

Afraid of broaching subjects that could land her on leave or dismissed from their position, Galloway continued to try to keep to themself. But the stress of closeting themself has been too much. And after years of a brewing — and arguably successful — culture war against gender and sexuality in public schools, Galloway is moving toward a new future outside of teaching, and out of Arizona, entirely.

“I just feel like anything can happen, and I don’t want to be here for it,” Galloway said.

Galloway is one of many LGBTQ+ people fleeing Arizona, where LGBTQ+ rights are hotly contested. LOOKOUT spoke with more than a dozen queer individuals over the course of two months who have either recently left the state, wanted to move, or are planning to move out of Arizona due to concerns about what the next four years or longer might look like. Their reasons for leaving vary, from health care to protecting their marriages. But there was one common thread:

Arizona is no longer safe.

Arizona has built a reputation for its independent political streak. Former Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, originally a Democrat, often clashed with her party’s efforts to enact sweeping changes. The late Sen. John McCain, a Republican, faced backlash from MAGA-aligned lawmakers for blocking his party’s attempt to repeal Obamacare during Donald Trump’s first term. Meanwhile, current Democratic Sens. Ruben Gallego and Mark Kelly have recently voted in near lockstep with Republicans more than other Democrats on key Senate bills and Trump-era confirmations.

At the state level, Arizona politics reflect a similar centrist trend. In the 2022 election, voters elected Democrats to the state’s three most powerful positions: governor, secretary of state and attorney general.

In the 2024 general election, voters approved a ballot measure adding abortion protections to the state constitution and rejected far-right Senate candidate Kari Lake. However, in that same election, Republicans — including far-right conservatives — won key positions that were seen to be safe for Democrats, securing seats in Maricopa County’s Attorney’s Office, Sheriff’s Office, school superintendent, and the state’s Corporation Commission.

And while Republicans previously held only a narrow majority by one vote in both chambers before this year, the party now has a four-seat advantage in the Senate and six seats in the House of Representatives. Though not a veto-proof majority, it’s enough to pass state resolutions and place measures on the 2026 ballot. Some of those proposals already under discussion target LGBTQ+ rights, including pronoun usage and bathroom bills.

While Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs still holds the power to veto bills targeting queer people — and she’s vetoed every one that’s come across her desk, so far — living at the mercy of someone else’s pen stroke has not provided a sense of safety for many Arizonans.

And the governor’s vetoes aren’t a guarantee: Last session, when Republicans attempted to bypass the governor’s veto regarding pronoun usage in schools and a bathroom ban for transgender children, Sen. John Kavanagh (R-Fountain Hills) introduced a Senate resolution that would have gone to voters. It failed by one vote — cast by moderate Republican Sen. Ken Bennett of Prescott, who was later defeated in his primary, largely due to that decision.

As a result of those political shifts, many Arizonans who were once proud to be part of a devil-may-care and Wild West state are now fleeing to other parts of the nation — and the world — where they foresee a more secure future.

In the past decade, multiple states across the South and Midwest passed laws banning drag from public spaces, hanging LGBTQ+ flags in schools or on public grounds, pushing for parental rights in schools, setting up tip lines for people to report teachers instructing “gender ideology,” and banning transgender students from playing in sports. Multiple LGBTQ+ advocacy groups advised queer people to avoid traveling to states such as Texas or Florida over safety concerns.

In that time period, there was an influx of stories where people — particularly parents of trans youth — moved their kids out of unsafe states to places where their children could live without politics bearing down on their lives.

Arizona was one of them.

“I couldn’t imagine moving back,” said Robert Chevaleau, who left Arizona for California in 2020 with his wife and two queer children.

While in Arizona, Chevaleau sought help with school policies that discriminated against one of his children, who is transgender. But no matter where he turned — from administrators to elected officials — he faced resistance.

“I expected my daughter could have long hair at school, wear a dress, wear earrings — I’m not even talking about bathrooms, just a dress. Surely that’s not unreasonable,” he said. He went from teachers to principals to school boards and finally the CEO of his daughter’s charter school to find someone to reason with. “And I was really surprised it wasn’t there.”

After multiple attempts to meet with local lawmakers in the House of Representatives and trying to negotiate with school leaders who were pushing anti-trans rules in schools, he and his wife decided it was time to leave.

“We’ve lived all over … you move for work or family and say, ‘OK, this will be a new adventure,’” Chevaleau said. “This was the first time we felt like we had to move. If we don’t move, our kids will not grow up to be confident and secure people.”

Shortly after the family moved, former Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed two bills targeting transgender children — banning surgeries and barring transgender girls from playing in girls’ sports.

Now, Cheveleau said both of his children are thriving away from the politics of Arizona, and doesn’t question his move. “When you have no one in leadership supporting you, it’s hard to get ahead and it’s hard to find your feet,” he said. “It’s just hard to catch your breath, which is really important when you’re a kid.”

But the attacks on trans people are extending beyond that community with conservatives who have long argued against same-sex marriage and legal protections for LGBTQ+ people. In Arizona, that would have far-reaching consequences if those were ripped away.

In 2022, 16 states had adopted marriage equality laws through legislation or voter initiatives. Today, 29 states — including Arizona — still have anti-LGBTQ+ laws, including same-sex marriage bans, in their constitutions or state statutes that have not been removed since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in 2015 with the Obergefell v. Hodges ruling.

That Supreme Court decision established that states had to recognize same-sex marriages and grant all people with marriage licenses the same state rights as everyone else, including property rights and rights of survivorship. In 2022, when the Supreme Court ruled in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization to overturn abortion as a right, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in a concurring opinion alongside the majority that the same reasoning for overturning abortion should be applied to same-sex marriage as well as sodomy laws.

Since that ruling, LGBTQ+ advocates have been bracing for a worst-case scenario of seeing a same-sex marriage case make its way to the Supreme Court.

In Colorado, voters amended the state constitution to allow same-sex marriage in the 2024 general election. In Virginia, lawmakers are advancing a resolution to place a similar measure on the 2026 ballot.

However, in Arizona, efforts to remove the ban from the state constitution have been blocked by Republican lawmakers, who have refused to allow bills on the issue to be heard in committee or receive public input.

Rep. Oscar De Los Santos, a Democrat from Phoenix and the state House minority leader, introduced a bill last year that would have put the issue before voters in the general election, but it was never given a hearing. This year, Rep. Brian Garcia, D-Phoenix, is attempting the same ahead of the 2026 midterms but has faced the same roadblocks of not being heard in a committee, which is the first step to getting a bill passed.

There is a stop-gap Arizonans are leaning on: Congress passed the Respect for Marriage Act in 2022, requiring states to recognize marriage licenses from other states. The federal law allows couples to leave their state to marry and return with their union recognized. But it remains unclear what would happen to marriages in Arizona and other states where bans are still in place.

Some advocates believe existing marriages would be grandfathered in, but no further marriage licenses would be issued. But others believe state bans could void marriages, stripping couples of key rights, including property ownership, medical visitation, automatic parentage and wrongful death claims, unless they marry outside the state. That outcome is less likely, they say.

The concerns extend beyond same-sex marriage. Arizona has no hate crime statute, despite multiple attempts by lawmakers to pass one. While there is broad support for nondiscrimination protections across Arizona, the state has no law preventing LGBTQ+ people from being evicted, fired or denied services. Protections exist only through a patchwork of city ordinances and an executive order shielding state employees — an order that a future governor could reverse.

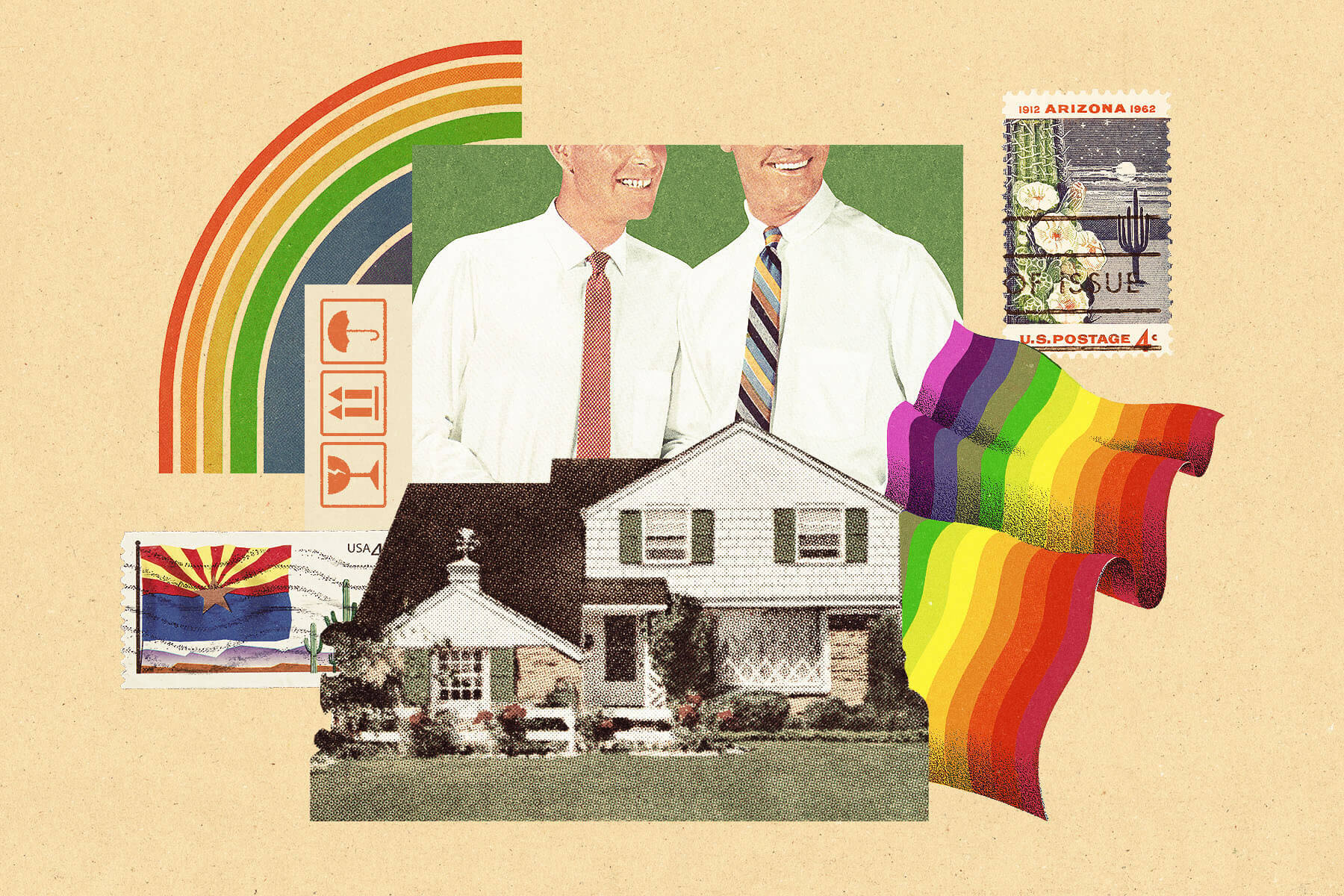

Married couple Blake Reeves and Nick Earl say they see “the writing on the wall” and are choosing to leave before their marriage rights could be challenged by the state.

Both men grew up in Arizona: Reeves in the Phoenix suburbs, Earl in Lake Havasu City in northwestern Arizona. When they bought their home in Phoenix’s midtown area, they intended to make it their forever home.

“We always joked about leaving, but we really like Phoenix,” Reeves said, explaining that they had no plans to leave the mid-century home they had renovated.

Both men’s families and all their friends still live in the state. They feel an affinity for the desert heat and the beauty of Arizona — to which Earl said he feels a “spiritual connection.” They never considered how politics might affect their lives as a couple.

“This is home, even if it comes with flaws we were OK with pushing through,” Earl said.

That is, until now. Reeves and Earl said they feel in limbo, unsure of what to do if the U.S. Supreme Court were to overturn its 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, which granted them the right to marry in their home state.

With Trump’s second term, they’ve noticed how emboldened conservatives have become in trying to reverse that decision. And their concern is not unfounded: In Idaho, the state’s Republican legislature filed a letter with the Supreme Court asking them to reverse the Obergefell ruling.

The Arizona-based Alliance Defending Freedom, which helped get Roe v. Wade overturned and lobbied for the Supreme Court case that removed discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people, is pushing to overturn same-sex marriage.

Late last year, Reeves received an offer to relocate his job to San Francisco, and the couple saw it as an opportunity to escape.

“I don’t want to sit around and wait for something to happen and it’s too late,” Reeves said.

What’s worse, they said, is that they don’t know if anyone with power in the state would — or even could — stand up for them.

“After the election, we saw officials in other states really take a stand and say that LGBT people would be protected,” Earl said. “It’s been crickets in Arizona.”

It’s unclear how many people are actually trying to flee Arizona. While there is a growing body of data analyzing LGBTQ+ migration into the United States and certain states, research on migration patterns of queer populations between states is not as robust.

The Trevor Project, a national LGBTQ+ advocacy group, identified in 2022 that Arizona was one of 10 states where transgender people, specifically, had moved out of due to state laws that targeted them or their families. Out of more than 90,000 transgender respondents, 5 percent said they had already relocated out of states such as Alabama, Arizona, Texas, Florida, Georgia and Ohio.

Last year, Data for Progress surveyed 1,036 people and found that 5 percent of all LGBTQ+ people surveyed across the nation had moved out of a state because of anti-LGBTQ+ laws. For people who identified as nonbinary or transgender, the number rose to 21 percent.

And just this year, The Trevor Project and Movement Advancement Project found that many LGBTQ+ young people and their families have had to consider leaving their state. Nearly two in five young people reported thinking about moving, and 4 percent of all respondents relocated.

But overall numbers are difficult to obtain: Other data, such as real estate listings, are less revealing since records only reflect a small portion of queer people who are married, own property together, and might be selling their homes. They don’t account for renters or unmarried couples looking to sell or rent out their homes.

To gauge the exodus in Arizona, there are only anecdotes from those who have already left or are planning to move.

But moving isn’t easy, and some people LOOKOUT spoke with have encountered roadblocks, whether due to a lack of finances to relocate to a safer place or, for those trying to leave the United States, immigration issues.

Galloway, the teacher from Tempe, is renting out their home and plans to move to Uruguay by the summer. However, before doing so, they need to renew their passport, which still lists their sex assigned at birth. Due to a new executive order and Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s decision to freeze applications with an X gender marker, Galloway has come to terms with the fact they won’t be able to change the legal documents to reflect their gender or name on their passport — a personal goal they had for the year. LGBTQ+ advocacy and civil rights groups, including the ACLU, are advising people who need gender markers changed on their passports to not do so right now.

For others, such as Jo and their wife, Cristine, the decision to move was complicated by finances. Both asked that their last names not be used, as one works for the federal government and fears retaliation.

The couple moved back to Arizona during the pandemic and had plans to stay. But with the recent election, they planned to use savings from moving home to buy a place in Northern California. They contacted a real estate agent and had put a bid down on a home close to San Francisco, but the house they were under contract with required extensive repairs — more money than they had.

When they were looking at other places they could afford in more rural areas, the people and politics of the region reminded them of the same areas they wanted to leave behind. So, they’re staying.

“The universe was just telling us things, and we decided to stay in Arizona, put our head between our knees and hunker down,” Jo said.

Because Arizona has community property rights for married couples, they felt the need to buy a home in Arizona to secure their financial future in case their marriage was no longer recognized. The only place they could afford was Florence, Arizona — a rural and bright red town that is mainly known for its state prison and famously MAGA-friendly Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb.

“Not all of us queers can afford to live in the Melrose district,” Jo said, referring to Phoenix’s de facto gayborhood. “You’ve gotta be a certain kind of queer to afford that, and we’re not those queers.”

Buying a house should have been a celebratory moment, Jo said. “It’s sad. It’s surreal. We’re first-time homebuyers, and we should be ecstatic about it, but I can’t even enjoy it because I don’t know what’s going to happen to us.”

Recommended for you

From the Collection