Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, tens of thousands of people in states with abortion bans have continued to access the procedure through telehealth. But two separate cases targeting a New York physician could test the laws put in place to protect doctors who prescribe and mail abortion medications, jeopardizing the future of abortion access across the country.

Dr. Margaret Carpenter has allegedly prescribed and mailed abortion pills to patients in Texas and Louisiana, both states where abortion is almost completely illegal. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has filed a civil lawsuit accusing Carpenter of practicing medicine in Texas without a license and violating the state’s abortion ban. In Louisiana, a grand jury has indicted Carpenter on criminal charges for allegedly violating the state’s abortion ban.

The cases test statutes known as shield laws, which have been passed in eight states since the end of Roe. The laws — enacted in California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington — say that the state government will not comply with civil or criminal prosecutions targeting health care providers who perform abortions from their home states, including mailing medication to patients in places where the procedure is outlawed.

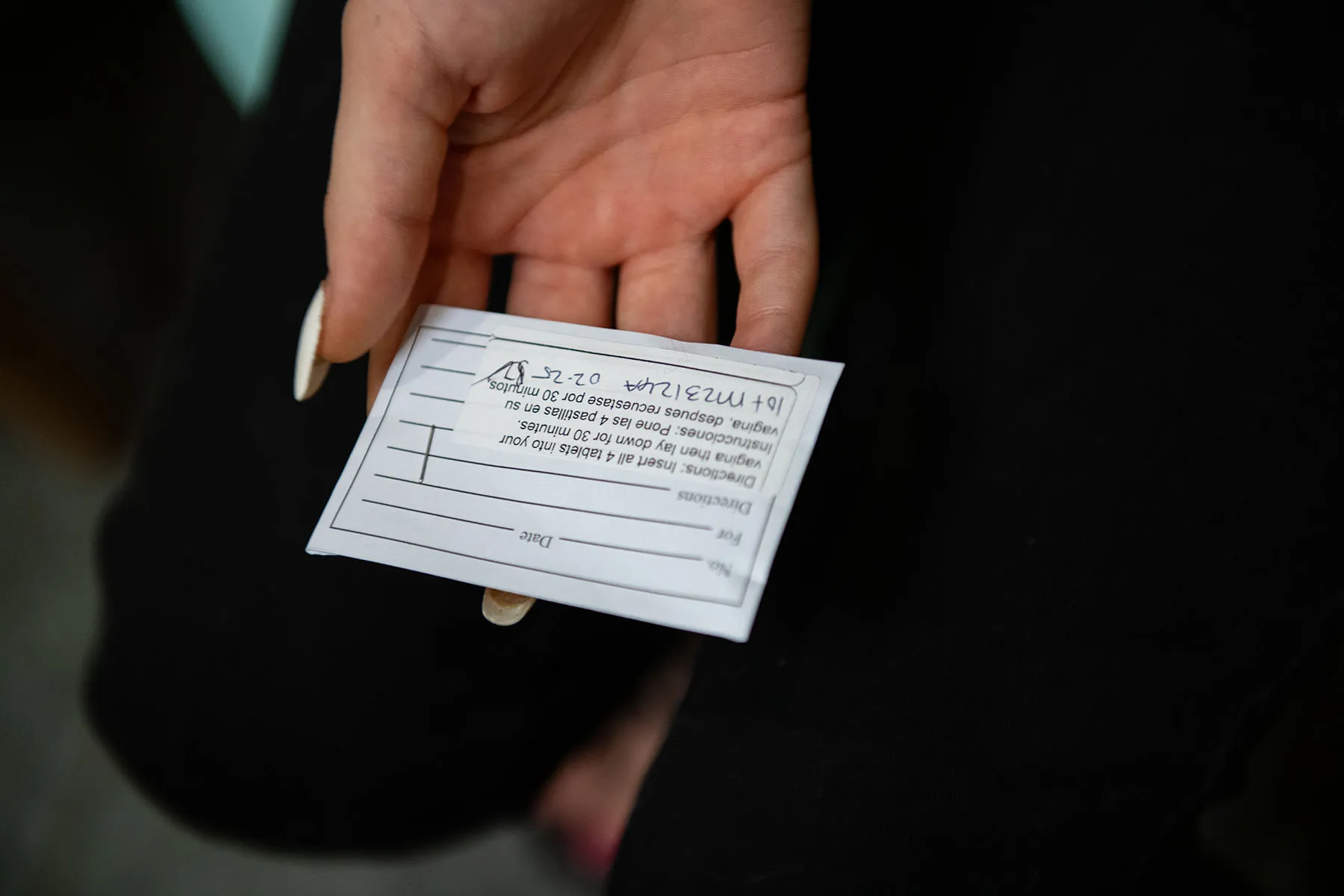

Those laws have enabled many people to receive abortions despite living in places with abortion bans. The Society for Family Planning estimates that close to 10,000 people in states with bans or restrictions get care through shield laws each month; between the start of 2023 and March 2024, it was more than 65,000 people. Research shows that providing abortion through telehealth, using the medications mifepristone and misoprostol, is highly safe and effective through the first trimester.

In Texas, a county judge issued an order Thursday blocking Carpenter from sending abortion medications to the state and fining her $100,000. Carpenter did not attend the hearing. The same day, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, in compliance with her state’s shield law, rejected a request from Louisiana’s Republican governor to extradite Carpenter.

“The ruling in Texas does not change that under Shield Laws, patients can access medication abortion from licensed providers no matter where they live. New York, led by Governor Hochul, remains committed to protecting this care,” Julie Kay, a lawyer who, along with Carpenter and New York-based shield law provider Dr. Linda Prine, co-founded the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine, said in a statement. Carpenter has not been reachable for comment. Prine declined to comment. Kay’s remarks were in a written statement.

Kay added that the Louisiana case is “inconsistent with New York state law,” and said the coalition will keep defending shield laws like New York’s.

The cases represent a remarkable evolution from less than three years ago, when, soon before Roe’s overturn, Republicans argued that they would not support policies that could put doctors in prison.

“The attempts to punish a provider who was providing what I understand to be legal care in her state for a patient who desired an abortion is aggressive and threatening,” said Dr. Jonas Swartz, an OB-GYN and abortion provider in North Carolina. “We’ve become desensitized to it, but it’s a really big deal.”

What comes next is the first test of the relatively new shield law infrastructure and the health care model it has enabled. These cases likely will not halt telehealth abortion immediately. But they are expected to yield complex, drawn-out legal battles — one that could end up in the U.S. Supreme Court — with vast possible ramifications.

The broader impact

Abortion opponents have voiced frustration with the prevalence of shield laws, and the workaround they’ve provided for patients seeking abortions. In Texas, anti-abortion activists are pushing for legislation to stop this practice. John Seago, the head of Texas Right to Life, has suggested that more cases, similar to the one against Carpenter, are in the pipeline.

There is a risk that cases like Louisiana’s and Texas’ could deter some providers from offering care through shield laws, Swartz suggested. But others who have been providing telehealth abortion — and relying on shield laws to do so — said previously that individual state-based legal actions would not necessarily stop them.

“We all have gone into this eyes wide open that we knew there would be legal challenges,” Dr. Angel Foster, a physician who co-founded a shield law practice called the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Project, told The 19th in early February. “We’re so confident what we’re doing is legal in the state of Massachusetts. Our practice complies with all laws, policies and regulations in the Commonwealth, so we continue to provide legally compliant, high-quality affordable abortion care, and will continue to do so.”

A California-based shield law physician, who asked that his name be withheld because of threats of violence against abortion providers, expressed similar confidence.

“I comply with California law to the letter and the spirit,” he said. “As long as it’s legal and ethical to provide these services, I can do so irrespective of other states’ actions.”

The legal battle

New York’s law is likely to prevent enforcement of Texas’ judgment, as long as Carpenter physically stays out of the Lone Star State, argued David Cohen, a constitutional law scholar at Drexel University who has advised many states on the construction of their shield laws.

“This case is very clear,” he said. “Dr. Carpenter would be on incredibly strong ground here and never have this judgment enforced against her in New York state court.”

New York’s shield law clearly says that the state will not extradite someone for providing an abortion if they did so while physically in the state. Because Louisiana alleges that Carpenter mailed medication to the patient — and did not come to Louisiana to do so — the Empire State is unlikely to comply.

Still, Carpenter could be at risk of extradition to Louisiana if she goes to another state, Cohen said, because the shield law’s protections only apply within New York’s borders. “If I were Dr. Carpenter, I would not leave the state of New York,” he said.

The Texas and Louisiana cases will likely progress to other courts.

Texas could ask a New York state court to enforce its judgment against Carpenter. But New York will likely argue that the shield law prevents it from doing so. The case would likely continue to progress through the state’s courts, and could possibly then be litigated in federal court — one with jurisdiction over New York.

Louisiana’s case would likely take a similar route, Cohen said. The state could pursue its extradition request in New York state court or, eventually, in federal court. Lawyers for the state could seek intervention from the Supreme Court as well.

That process could take months or even years, involving questions of state extradition and jurisdiction that have not been litigated in more than 150 years. Some observers believe the case could be resolved at the Supreme Court.

Federal involvement

Some suggested that a greater threat to broader telehealth than these court cases would be any federal action meant to disrupt shield laws. When federal and state laws conflict, federal laws typically triumph.

President Donald Trump said on the campaign trail that he did not want to take federal action to restrict abortion, saying instead that the issue should be left up to individual states. But earlier this month, Attorney General Pam Bondi said she would “love to work with” Louisiana prosecutors to stop shield law-backed health care.

It’s not clear what that might look like in practice. The Justice Department does not play a role in resolving disputes over extradition, Cohen said, and could not on its own compel New York to satisfy Louisiana’s request.

But one avenue for federal action could be launching a separate case and invoking an 1873 anti-vice law called the Comstock Act, which has not been enforced in decades but was never repealed. Anti-abortion activists believe it could be used to halt mailing of abortion medications.

Under President Joe Biden, the Justice Department said it did not believe Comstock prohibited mailing these pills. But abortion opponents have been pressing the Trump administration to change that policy. The Supreme Court’s most conservative members, Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, have also expressed openness to that legal interpretation.

That approach, too, could spark its own legal battle.

“If there was any meaningful reinterpretation [of Comstock], I think lawsuits would be fast and furious,” Foster said.