Republicans who control Congress are reportedly weighing cuts to Medicaid, the popular federal-state insurance program that provides health and long-term care to millions of Americans. Lawmakers have indicated the cuts would help pay for President Donald Trump’s tax policy, which is expected to include permanent tax breaks for wealthy Americans.

On January 31, Trump said he would “love and cherish” Social Security and Medicare — two programs that disproportionately provide financial support and care for older Americans — as well as Medicaid.

“We’re not going to do anything with that, unless we can find some abuse or waste,” the president said. “The people won’t be affected. It will only be more effective and better.”

Nearly two weeks later, House Republicans formally tasked lawmakers who oversee the Medicaid budget to slash at least $880 billion in spending over 10 years.

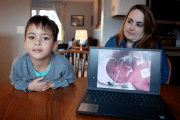

Medicaid serves about one in five Americans, and its supporters note it was not a key policy discussion between the major party candidates during the 2024 presidential campaign. On the receiving end of potential reductions to Medicaid are people: families — in particular pregnant people, mothers, caregivers and children. Some of these children also have complex medical needs and disabilities that advocates say could be impacted if the federal government halts some of its existing financial support.

As the future of Medicaid funding continues to be a part of the national conversation, here’s what you need to know about how it currently ensures quality health and long-term care for large swaths of people.

How many people are on Medicaid, and who are they?

About 72 million people are enrolled in Medicaid, a program created by law in 1965 that is funded by both the federal government and states to provide health insurance to low-income people, children, individuals with disabilities and some older Americans. Enrollees pay little to no money in premiums or fees because they struggle to afford health care.

In addition, there is the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, which ensures children whose parents earn too much to qualify for Medicaid — but are also priced out of affordable private insurance — are still able to access health care. That group represents about 7.2 million children, for a total of just under 80 million people on Medicaid.

Combining Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, nearly half of all people on Medicaid, 37.6 million, are children.

Here is a breakdown of other enrollees, according to available data:

- Parents and other adults under 65: 27.8 million

- People with disabilities: 7.8 million

- Individuals who are 65 and over: 5.6 million

The impact of Medicaid on women’s health is in the data. The program covered 19 percent of adult women ages 19 to 64 in 2023, compared to 14 percent of men. One in five non-elderly women in the United States are enrolled in Medicaid. Low-income parents who are on Medicaid are disproportionately women, according to Joan Alker, executive director of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

“There’s a lot of ways in which gender, and women in particular, are at risk when we have these kinds of proposals for broad cuts,” she said.

-

Read Next:

What services does Medicaid offer for pregnant people and new parents?

Medicaid provides health care coverage to low-income pregnant and postpartum people, a staple of the program since its inception nearly 60 years ago. Under Medicaid, pregnant people who need prenatal care are generally able to access vitamins, doctor’s visits and ultrasounds — benefits that improve the health of mothers and other caregivers.

“People of reproductive age really can benefit from having that steady coverage and going into pregnancy healthier,” said Laura Harker, a senior policy analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “So we really look at Medicaid across the reproductive journey.”

The program is credited with covering more than 40 percent of all births in the country. There are many variables to how much an uninsured person will actually pay for a birth, but experts estimate that a person with private insurance incurs an average of nearly $19,000 in health costs related to pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care — and that can translate to nearly $3,000 in out-of-pocket costs.

In short, Medicaid has served families for decades.

“It’s really hard to overstate the importance of Medicaid for kids and families,” said Maddie Twomey, communications director with Protect Our Care, a health care advocacy group. “You could rely on it at any point in your life.”

Under a provision in former President Joe Biden’s 2021 American Rescue Plan Act, states have recently been able to provide postpartum coverage for 12 months — up from a mandatory 60 days that had led about 45 percent of postpartum people to become uninsured shortly after the birth of a child.

More than half of pregnancy-related deaths in America occur in the first year after a birth, and these disparities disproportionately impact Black women.

To date, most states have agreed to expand postpartum coverage, which experts believe could help address health disparities that cause pregnancy-related deaths. A year of postpartum coverage can also help parents address postpartum depression, which may not appear for months, as well as medical debt.

Some policy experts caution about drawing definitive conclusions yet on the effects of the extended postpartum coverage period but agree that the U.S. maternal mortality rate remains stubbornly high — one estimate by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put it at 23 deaths per 100,000 births between 2018 and 2022 — compared to other countries.

Health advocates worry that general cuts to the Medicaid program would inevitably impact whether as many states offer extended postpartum coverage as they try to offset the federal government reducing any matching funds it has provided.

What does Medicaid do for children?

Through Medicaid and CHIP, millions of the nation’s children are able to access a range of health care: checkups and emergency care, dental and vision, laboratory and X-ray services, vaccine immunizations, mental health and other services.

That results in better overall health as children age into adulthood. There are other benefits, too: a lower high school dropout rate, higher college enrollment and completion rates and higher wages later in life.

“It’s one of these things that works so well, it’s ultimately a really good investment,” Twomey said.

Medicaid also plays a major role in care for children with complex medical needs and disabilities. Data from 2019 estimated there are 13.9 million children with special health care needs in the country. Medicaid covers almost half of them, according to KFF, a health policy research nonprofit.

Children (and adults) with such special health needs may require what’s known as long-term services and supports — which includes home and community-based services. Those services can include attendant care, assistive technology, case management and private duty nursing which allows children to live at home with their families instead of institutionalized care. Depending on the state, Medicaid pays for many of those services when private insurance often does not.

“It is the lifeline for children with complex medical needs and disabilities, unless you’re independently wealthy,” said Elena Hung, executive director and co-founder of Little Lobbyists, a national advocacy organization for children with such needs.

School districts also use Medicaid dollars to provide certain medically-necessary services to eligible students under a federal disability law aimed at addressing education needs. Medicaid dollars pay for professionals like speech-language pathologists, audiologists, occupational therapists, school psychologists and school social workers who provide services to eligible students.

-

Read Next:

How else does Medicaid impact overall caregiving?

Medicaid covers half of all long-term care spending, according to KFF. That care is key for women, who live longer than men. In 2021, 20 percent of women were dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, a supplemental coverage setup that helps them and others pay for more of their care needs.

Medicaid pays for more than 60 percent of long-term care residents in nursing homes, a population that is heavily women. Many in the care workforce are also women, and largely women of color. Their low wages mean many rely on Medicaid for their own health care coverage.

“It’s permeating so many different aspects of our health care system that relate to caregiving,” said Alker, who noted just over half of Medicaid spending goes to seniors and people with disabilities.

Over several years, most states and the District of Columbia have also expanded who qualifies for their Medicaid programs under the Affordable Care Act. Getting rid of that expansion is among the proposed cuts by congressional Republicans, to the tune of $561 billion over 10 years. Alker said overall reductions to the program is likely to impact all enrollees and that it would be detrimental to children.

“They’re not protecting children by pulling out hundreds of billions of dollars from the most important program there is for children’s health, because states would not be able to make up for these kinds of losses,” she said. “States would be left in an extremely untenable position. So fiscally, it’s a huge risk to children.”

Is Medicaid popular?

Yes, it’s a popular program among a majority of Americans, according to KFF polling that was conducted in January ahead of Trump’s inauguration. The findings show 77 percent of respondents view the Medicaid program favorably. That included 63 percent of Republicans.

The poll also found nearly half of all people say the federal government is not spending enough on Medicare and Medicaid.

Is there fraud in Medicaid?

There are reports that Elon Musk, designated by Trump to cut the size of the federal government even though those efforts so far include trying to halt the flow of money already appropriated by Congress, has been given access to technology and spending information on Medicare and Medicaid — programs housed under the federal health department. Musk claimed on X: “Yeah, this is where the big money fraud is happening.”

The scope of fraud in health care is nuanced but is not often committed by regular people who are Medicaid enrollees. According to an estimate by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, 95 percent of Medicaid payments are proper payments for care. There are also already systems in place, including through the federal government, to catch and prosecute fraud and forms of mismanagement.