This story was published in partnership with The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence.

Adrienne Rodriguez held her head high as she walked to the front of the courtroom. On her right, her friends and relatives filled the three wooden pews in the back of the room. To her left, the rows on the defendant’s side sat empty.

Rodriguez was at the DeKalb County Courthouse in Georgia on that muggy Wednesday morning in August to give a victim impact statement. The room was quiet as she took the stand. Her eyes focused on the accused, whom she once considered a son, now seated next to his public defender. Rodriguez fixed the top button of her pink blouse and took a deep breath before speaking to the charges: second-degree murder and feticide. She would tell the judge she did not think it was right for the man before her, her daughter’s long-term boyfriend, to go free before his trial.

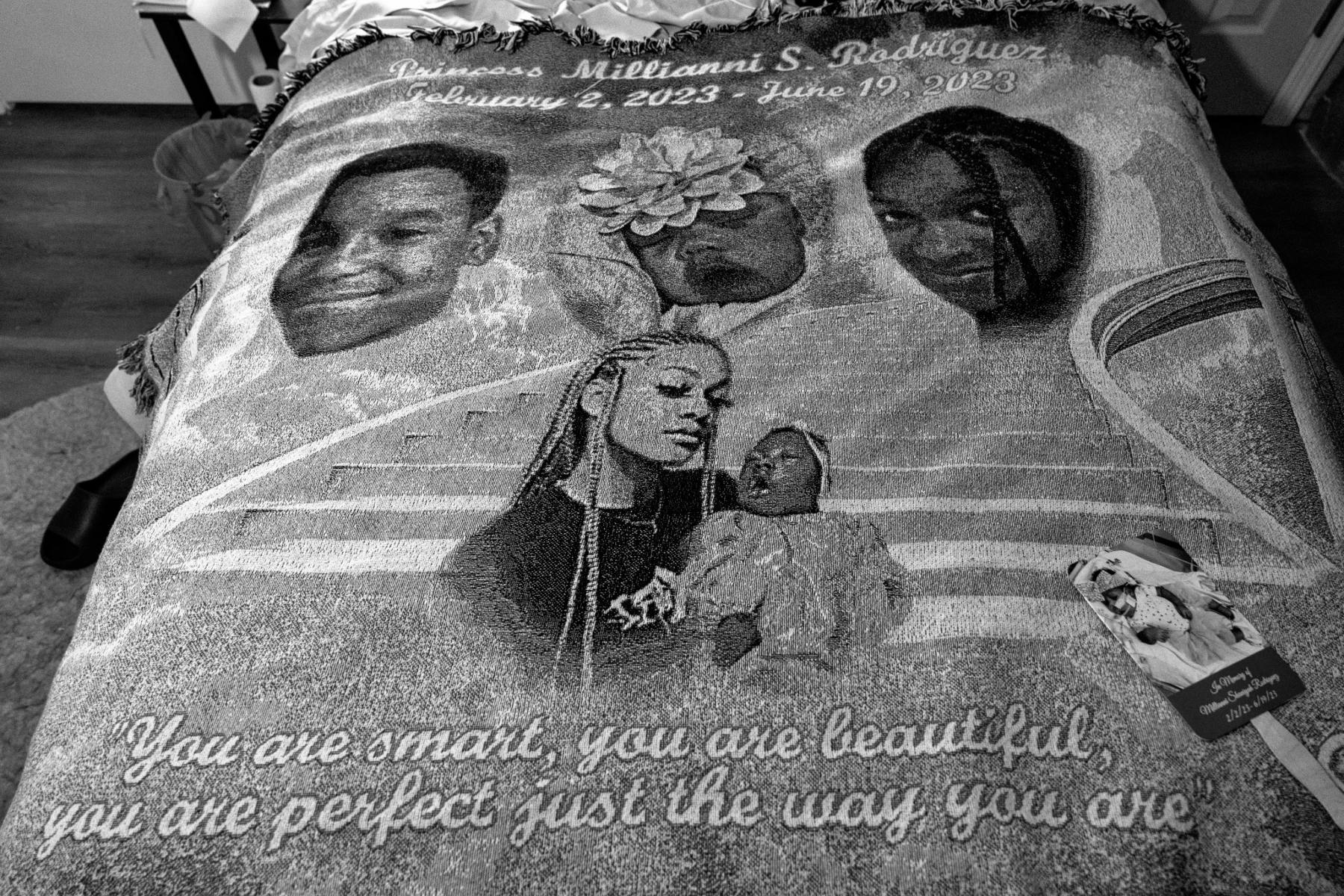

More than a year earlier, in February 2023, Rodriguez’s only daughter, Shaniyah Rodriguez, was shot and killed, leading to the premature birth and eventual death of her child. The baby had depended on a respiratory machine for 137 days, during which her grandmother hardly ever left her side. She had named her Millianni.

“Shaniyah wasn’t just my daughter, she was my best friend, and I know that Millianni was my grandchild but she was my daughter, too,” Rodriguez told the court, struggling to continue. “Millianni took her last breath in my arms, but she was supposed to make it. She is supposed to be here.”

Twenty minutes after Rodriguez returned to her seat, the judge denied bond. Shaniyah’s family clapped and cheered. It was a welcome moment of relief from the grief they’d carried since the shooting. They had each struggled with nightmares and doubt, but perhaps none more than Rodriguez, who was racked with guilt, unable to sleep or work as she fixated on the events that led to her daughter’s death.

She is not alone. For decades, researchers, epidemiologists, domestic violence advocates, and media reports have been sounding the alarm on a longstanding American reality: Pregnant women and birthing people are more likely to die by homicide than any obstetric-related cause. At the center of the crisis is the firearm — used in a majority of these killings, most often at the hands of intimate partners. Young women under the age of 25 and Black women bear the brunt of this violence but are often overlooked in efforts meant to address it.

The startling reality of pregnancy-related and postpartum killings by firearm dates back decades, but a full picture of the crisis is still evolving alongside the growing national tumult over reproductive rights.

“Women experiencing intimate partner violence are not who are immediately thought of when discussions of gun legislation or changes in reproductive access come up,” said Rebecca Lawn, a public health scholar at Harvard University who studies interpersonal violence. She was shocked when she first learned the extent to which pregnant women are at risk. “But, the bottom line is, these deaths are preventable.”

For the families who are coping with this kind of loss, the pain and guilt can be immense. They mourn not only who their daughters were, but who they were or could have been as mothers. And, had the children they were carrying lived, those same families can only imagine who they might have grown up to become.

“I was so hopeful that Millianni would survive,” said Rodriguez. “People around me were like, just give up, but I was like, ‘no, she has to make it, I can’t lose them both.’”

The stories numbers can’t tell

When Shaniyah Rodriguez was born in the Atlanta area in the fall of 2002, local obstetric specialists had just published one of the city’s first, most comprehensive studies of maternal death records. By analyzing the deaths of pregnant and postpartum women in one of the area’s hospitals from 1949 to 2000, the study found that a spike in homicides, first apparent in the 1970s, was outpacing other obstetric causes of death.

The Atlanta study was ahead of its time. In the mid-1990s, more researchers began to examine the maternal homicide crisis on regional and local levels, often by gathering death records and autopsies to parse out connections to criminal outcomes. Those efforts unveiled key aspects of the crisis: in Maryland, vulnerability was shown to be age-specific; in North Carolina, homicide accounted for the most injury-related maternal deaths; and in Illinois, more than half of the state’s fatal pregnancy shooting victims resided in one county. The availability of national data only emerged in 2003, as states began to slowly share statistics with national agencies. It took years for pregnancy-related homicides to be recognized as a form of maternal death by obstetric leaders, but in 2018, due to a revision of the death certificate used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a national death rate could finally be calculated.

The nationwide data showed the same patterns first revealed in the more granular studies: a majority of these deaths were intimate partner-related and took place in the victim’s home. All told, 60 to 80 percent of pregnancy-related homicides are by gun.

Even as a clearer quantitative picture came into view, almost all of the research published on perinatal homicides in recent decades has lacked qualitative detail. Firsthand accounts of frontline clinicians, family members, survivors and medical practitioners are rare, obscuring ground-level similarities in the circumstances and outcomes of pregnancy-related violence, and their differences.

Research is vital, but the stories of these women paint a more complete picture not found in the data. In the details of the lives of young women like Shaniyah, and her mother who survived her, the scope of what has been lost comes into focus. The ties between these shootings and the criminal legal system can be better understood through surviving family members’ search for justice, as in the efforts of one mother in Florida who buried her teenage daughter two years ago, or a Wisconsin mother who celebrated her daughter’s pregnancy one week before losing her to a fatal shooting. The story of one shooting survivor in Louisiana, who has been paralyzed from the neck down for 12 years and is still racked with guilt, lays bare potential prevention strategies.

The study on maternal deaths in Atlanta, published the year Shaniyah was born not too far from the city, was updated four years before her death. By then, homicide had become the leading cause of pregnancy-associated death at Grady Memorial Hospital. Shaniyah would die there of a gunshot wound in 2023. She was 20 years old.

Gaps in the system

Adrienne Rodriguez recalled the morning of February 2, 2023, vividly. Her phone flashed a number that she didn’t recognize but felt compelled to answer. The operator said her daughter’s name and told her to get to Grady Memorial right away; she thought Shaniyah must be in labor. As she rushed to the hospital, she said she repeatedly called Shaniyah’s boyfriend to check on her condition, but he didn’t answer.

Shaniyah had given birth, by emergency C-section, delivering a 5-pound, 2-ounce baby girl who lay in the newborn intensive care unit, experiencing rounds of seizures. But Rodriguez wasn’t taken to see the baby. Instead, she was directed to a hospital room where her daughter lay unconscious, bloody bandages wrapped around her head, a single gunshot wound to her left temple.

“When I saw her, I just started screaming and was asking where was the baby,” said Rodriguez. “When she got shot I wondered if she was thinking, ‘Where is my mom,’ because I am the one that’s supposed to protect her, that’s my job.”

Pregnancy can often be the most dangerous time in a birthing person’s life. Pregnant and postpartum women are 16 percent more likely to be homicide victims than their non-pregnant women peers, and the CDC estimates that 6 percent of people who have recently given birth experience some form of intimate violence. The number is an estimate, and likely an undercount. There is no national agency monitoring domestic abuse during prenatal and postpartum care — still just a fraction of the 1.5 million women who are exposed to this type of violence annually. Despite the urging of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, around half of the pregnant people who experience intimate partner violence are not screened for it during or after their pregnancy.

“The challenges in building trust, and slowing down enough to think about the pregnant person in the context of their relationships, is not done in modern pregnancy care in this country, and it’s a missed opportunity,” said Dr. Amrapali Maitra, an internist at Stanford University. “New moms don't have time to access the health care system, and the health care system doesn’t come to them, so you are left with people in an incredibly vulnerable time, who don't have consistent contact with the healthcare system if violence is escalating.”

Medical students in the U.S. are not typically trained in how to recognize domestic abuse and lack access to tools that have been shown to support patients, such as connecting with domestic violence advocates who can help provide safe housing or childcare. An already strained system is being stretched further by a growing shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists, and fewer medical students applying for residency in gynecology after Roe v. Wade was overturned, a potential void in care that could worsen outcomes for those experiencing interpersonal violence.

Rodriguez has spent the time since her daughter’s shooting searching for the signs of abuse she could have missed. Having had her own first child the week before turning 16, she remembered being happy that her daughter had graduated from high school before she’d become a mother. “Shaniyah was not excited to be pregnant at first. She was asking me, ‘Ma, can you send me out of the state to have an abortion,’” Rodriguez said. In Georgia, a six-week abortion ban has been the status quo since 2022. “But around the fifth month, she got more excited and prepared herself to become a mother.”

Teenage motherhood was an experience that Paula Davis knew well. She was 17 when she became a mother for the first time, forgoing a college soccer scholarship to have her baby. When her daughter De’Shayla became pregnant at 15, she didn’t want her to have to make the same sacrifices she had.

“I talked to her about things like abortion, but I just know how hard it is, so I just wanted her to know all her options,” she said from her home in Orlando. But her daughter was adamant. “She wanted to have her baby, so I supported her.”

But on an October night in 2022, as Davis had just finished an eight-hour restaurant shift and was driving home with her oldest daughter, their phones rang and chimed simultaneously.

“Mama, somebody shot Shayla,” yelled Davis’s daughter. Davis’s heart raced, her vision blurred by tears as they drove to the scene of the shooting.

“I could feel the air leave my body, I just needed to get to Shayla and make sure that she was okay,” said Davis, recounting the scene. “And I get there, I just see Shayla’s body lying on the ground and I know that she’s dead. I screamed a scream that I didn’t know I had in me.”

It was four days after De’Shayla’s 16th birthday. She had been five months pregnant. The man believed to be the father of De’Shayla’s unborn child has been charged with committing second-degree murder and feticide.

Deadly disparities

For young women like De’Shayla and Shaniyah, their age significantly contributes to their likelihood of being shot while pregnant. For pregnant people under the age of 25, there is a more than 65 percent increase in homicide rates. But age is only part of their vulnerability. Research also shows that their race placed them at a higher risk.

Between 2008 and 2019, Black women represented half of pregnancy-related shooting victims, despite making up only about 13 percent of women of reproductive age. A more recent analysis of all forms of homicide found a similar figure. A 2021 report led by researchers at the University of Indianapolis found that peripartum Black women were eight times more likely to be homicide victims than their non-pregnant counterparts.

Nationally, Black women are three times more likely than white women to die of obstetric-related causes, such as hemorrhaging or sepsis, regardless of income or education. The root causes of these maternal death disparities, experts said, should be addressed by public health interventions that combat structural racism, such as the expansion of Medicaid, which would make abortion more accessible and increase access to prenatal services.

“We are starting in a place where Black women walking into medical systems are already up against insurmountable medical racism,” said Maeve Wallace, a reproductive epidemiologist at the University of Arizona who has studied pregnancy-related homicides for more than a decade. “So, when people are fighting to be heard when they are communicating that my blood pressure is too high, imagine having to say, ‘there is something not right, I am experiencing violence,’ or other things that are extremely sensitive.”

In Wisconsin, the state with the highest femicide disparity gap in the country, Black women were 20 times more likely to be murdered than white women in 2020.

“It is not surprising, but it is striking, that this type of harm is being done to pregnant Black women but is unfortunately consistent with the fact that Black women are often the most vulnerable in many health disparities,” said Antonia Drew Norton, director and founder of the Asha Project, a domestic violence organization based in Milwaukee that provides transitional shelter and trauma support to Black women.

Norton is working with Carrie Hickles, the mother of a 28-year-old pregnant Black woman who was fatally shot in February. Kuvina Hickles was 33 days pregnant — an early stage in which potential victims are the most vulnerable to violence. The Asha organization is working to support Hickles as she attempts to get her daughter’s case solved. Hickles, who suffers from various health issues, said the pain of losing a pregnant child violently is only intensified by the lack of answers. The organization has been “a lifeline” as she has struggled to get answers from the district attorney’s office or the Milwaukee Police Department, which would not comment on an open investigation.

“To them, she is just another Black statistic. They don’t care… because they haven’t lost a child like this,” said Hickles tearfully as she tried to catch her breath. “Kuvina was so happy when she found that she was pregnant, and this would have been my first grandchild. We had so many plans.”

Where reproductive rights intersect with the gun

As race, age or economic status consistently contribute to rates of gun homicide among pregnant people, another risk factor is emerging: access to reproductive care. A study published earlier this year showed that in states with restrictive abortion policies, the rate of peripartum homicide was three-quarters higher. Another published last month similarly found that states that limited divorce during pregnancy had higher rates of pregnancy-related homicide than states without such policies.

“[The results] confirmed my concern that women, especially young and Black and Hispanic women, would be endangered by laws that restrict their reproductive care access and rights,” Kaitlin Boyle, a criminologist who led the study, told The Trace via email. “Pregnancy is a vulnerable time in which partner abuse may start or escalate,” so in states where women cannot easily divorce violent partners or are prevented from seeking reproductive care, Boyle added, they are more at risk for fatal violence.

In Florida, where De’Shayla was killed, there is a six-week abortion ban. A ballot measure to protect abortion rights fell short in November’s elections, with 57 percent of Floridians voting in favor of the amendment, short of the 60 percent majority needed for it to pass. In Wisconsin, where Kuvina was shot and a temporary 20-week abortion ban is in place, Medicaid is not permitted to cover most abortion care, and the state Supreme Court is considering enforcing an abortion ban dating back to 1849.

(Asher Imtiaz for The Trace)

In Georgia, where Shaniyah Rodriguez died along with her premature daughter, there is a six-week abortion ban. For her mother, though, it is not only reproductive laws that need to be called into question, but also the state’s firearm laws, which allow for concealed carry but lack background checks, secure storage, and extreme risk protection orders. These laws hit home for Rodriguez, who has now lost two of her three children to firearms. In 2014, on the eve of his 13th birthday, her son Nizzear was shot to death as he slept at his father’s house.

“When I lost my son to gun violence, it destroyed me. I lost myself,” said Rodriguez, who would lose her daughter to gun violence nine years later. “The pain of losing a child in such a traumatic way really took something out of me, and for it to happen again, I don’t know how I will be able to find myself again.”

Research has shown that in scenarios where abusers have access to a firearm, victims are five times more likely to die. Experts are beginning to explore the relationship between firearm access and perinatal deaths. Earlier this year, Wallace, the researcher from the University of Arizona, received a grant to study pregnancy violence and extreme risk protective orders (ERPOs), commonly referred to as red flag laws, which temporarily seize the firearms of a person deemed a potential threat to themselves or others.

“For a pregnant person in an abusive situation who knows that pregnancy is a risky period, maybe a solution is them filing an ERPO as opposed to a restraining order,” Wallace said. “They may not want their partner removed from the home as they prepare to have a child, but to have their firearms temporarily removed as they get through this stressful time, and hopefully with that comes resources to prevent violence in the first place.”

A mother's grief

Most of the media reports and attention have focused on the victims of deadly pregnancy-firearm violence, but the voices of the rare survivors are often unheard.

In June 2012, while four months pregnant, 23-year-old Kayla Lee Atkins’ estranged husband shot her four times as she sat in a car, paralyzing her from the neck down.

Atkins, a mother of two, lay in her hospital bed at a Baton Rouge hospital weeks after the shooting — still 23 weeks pregnant — when she felt a familiar pain. Her mother lifted her blanket and gown and saw the head of a baby easing out.

“Her eyes weren’t completely developed, and she was blowing bubbles like she was trying to breathe, and we just started screaming,” recalled Jewel Lee, Atkins’ sister. “That is a sight that I will never forget.”

Charitee Shyne lived for three-quarters of an hour — during which Atkins was sedated — but her aunt remembered how the baby lay on her mother’s chest as she took her last breaths.

“We dressed her in babydoll clothes,” Lee said. “She was so tiny that she couldn’t fit any of the baby clothes yet.”

Her family buried Charitee on her big brother’s fourth birthday, her tiny body placed in a brown box padded with some cloth. As the family gathered to say goodbye to Charitee, the birthday boy pointed, smiling, and asked, “Is that my birthday gift, Mama?”

The guilt weighs on Atkins daily. “I blame myself, because of the person that I dated. There were signs and I kept going back because I felt like it was love. I put us in this situation,” she said. “My mom has stopped her life for my kids and for me, so my kids wouldn’t have to go to foster care, or I wouldn’t be left in a nursing home. No one treats me like my mom.”

The immediate aftermath of Atkins' shooting received local media attention, and even the district attorney came to visit her during her 10-month hospital stay, which she saw as an acknowledgment that the system had failed her. Yet data shows that pregnancy-associated violence in her home state, and nationwide, has only increased. The community of survivors that Atkins represents is uncounted, as there is no available data on how many pregnant people and their fetuses survive firearm violence, according to the CDC.

But Atkins is grateful that her shooter has been brought to justice; in 2014, her estranged husband was found guilty of attempted murder and second-degree murder, and sentenced to life plus 50 years. But she doesn’t feel that she will ever get closure. “Even if I get an apology from him, what is that going to do? It’s not going to make me walk again and it’s not going to bring my child back.”

As the years pass, her family still finds themselves envisioning a different reality.

“I see other people doing things with their mom, and I wish we could do those things like dance together, or go shopping or even swimming, and I will never get that chance,” said Atkins’ 14-year-old daughter, Zerrani, as she held up the neck rest on her mother’s wheelchair to make her more comfortable. “And I always wonder what it would be like if my little sister survived.”

Exactly 11 years to the day Kayla Atkins was shot, in 2023, Adrienne Rodriguez dressed her granddaughter in a white gown and white bow. She was aware that Millianni didn’t have much time left to live, but wanted to make sure that she was baptized. The hospital staff came in to make sure that she had everything that she needed, and Rodriguez smiled as her granddaughter’s little frame was gently dipped in the lukewarm water. Shortly after, Rodriguez held her granddaughter in her arms for the last time and played a song that her daughter Shaniyah recorded before her passing.

"She didn't fully coo, but she made an ‘ahh’ noise, and that was the first time I heard her little soft voice.” As the song finished, Millianni took her last breath.

This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2024 National Fellowship, through the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.