This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

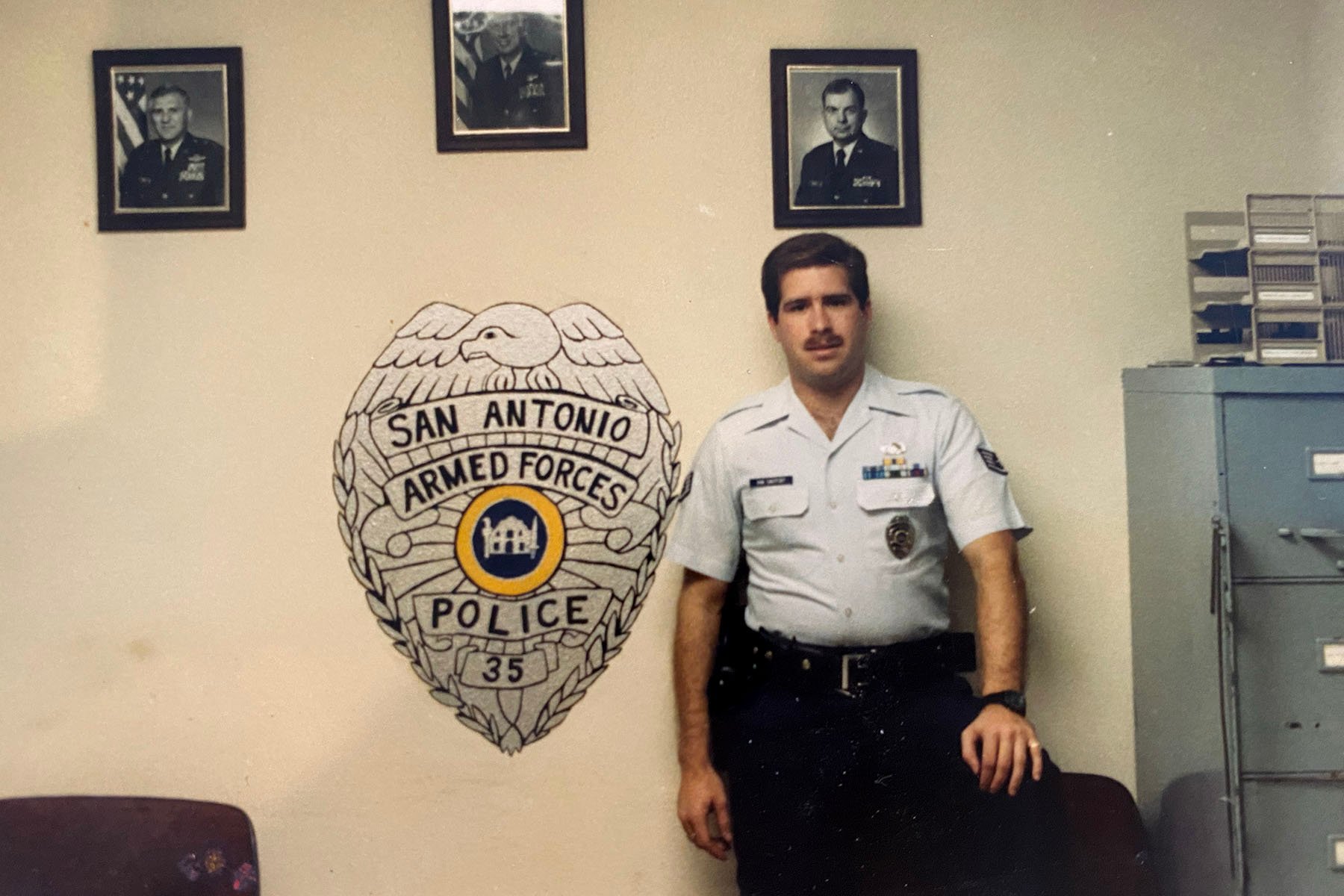

On weekends, Staff Sgt. Todd VanCantfort, an armed forces police officer in San Antonio, Texas, targeted gay bars in search of anyone in the military. One time, at the direction of his supervisor, he ditched his light blue and navy uniform to “dress gay.” He chose tight jeans, cowboy boots, and an open button-down shirt, advertising a burst of chest hair.

It was 1985. San Antonio was dotted with several military installations and even more bars, many of them rowdy dance clubs where VanCantfort would break up fights or drive slurring servicemembers back to base.

At the gay clubs, though, his orders were clear—round up anyone in the military and turn them in, so leadership could kick them out.

“Victimizing the people for no reason,” is how VanCantfort now describes it.

Forty years later, those witch hunts sound archaic. But they cast a long shadow over a military still struggling to make amends—and now serve as a reminder of a disturbing legacy as Donald Trump returns to the White House next year. His now-embattled choice to lead the defense department, Fox News host and former National Guard soldier Pete Hegseth, has declared a war on “woke.”

He’s railed against women in combat, transgender rights, and diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts that he insists have demoralized troops and weakened our fighting forces. Whether the controversial Hegseth is confirmed or not, his nomination has rekindled the question of who is welcome to serve in the United States military. And Trump’s ties to the authors of Project 2025, a conservative and controversial blueprint for his second term, adds to the uncertainty.

For those caught up in the witch hunts that rooted out LGBTQ service members, the disgrace is everlasting.

“I don’t know how to explain to somebody what it feels like when your own military that you volunteered to fight for your country doesn’t want you,” says Elaine Rodriguez, who was outed as a lesbian and kicked out of the Navy in 1991. She still mourns the military career taken from her and the self-worth that never fully rebounded.

Stories like Rodriguez’s have recently inspired pardons and other actions by the White House and the Defense Department. But, as The War Horse has reported, those efforts have benefitted only a fraction of the tens of thousands of gay and lesbian veterans who were kicked out. Still, advocates hoped that the small gains made under President Biden would lead to more sweeping action. That now seems unlikely.

It’s not exactly deja vu, said Rodriguez, now 58 and living in Jacksonville, Florida, but it is “scary” that once again people who want to serve may be forbidden from doing so, much like in the 1980s.

She and VanCantfort are sharing their stories with The War Horse—from opposite sides of the witch hunts—to shed light on a painful and calculating discriminatory past that they say must not be forgotten.

How the raids went down

VanCantfort, now retired and living outside Washington, D.C., was among a cadre of police officers, criminal investigators, commanders, and JAGs across the globe who executed the military’s anti-gay policies that stretched from the 1950s through the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” in 2011 and resulted in the dismissal of about 100,000 servicemembers.

In those days, when the staff sergeant pulled up to a gay club, it often would unfold like this:

Intimidate the crowd just by walking in, ask for the military IDs of people they recognized or suspected were in the military, and haul those folks back to their base, outing them to their commander. License plates with military decals in the parking lot were jotted down and reported.

On occasion, though, things went sideways. One night, he remembers arriving with two or three other officers at a smoke-filled country western lesbian bar on the outskirts of San Antonio. When they entered, the twangy band stopped playing. The lights popped on.

Someone—the bar owner—barked into the mic, telling her patrons to protect their friends in uniform.

The women stood shoulder to shoulder, forming a wall, allowing any scared service member to flee through a back exit. Because most of the women in the bar were civilians, they knew the armed forces police wouldn’t arrest them. They inched so close to VanCantfort, he could feel their anger and their message was clear—get the fuck out; leave us alone.

Making her family proud

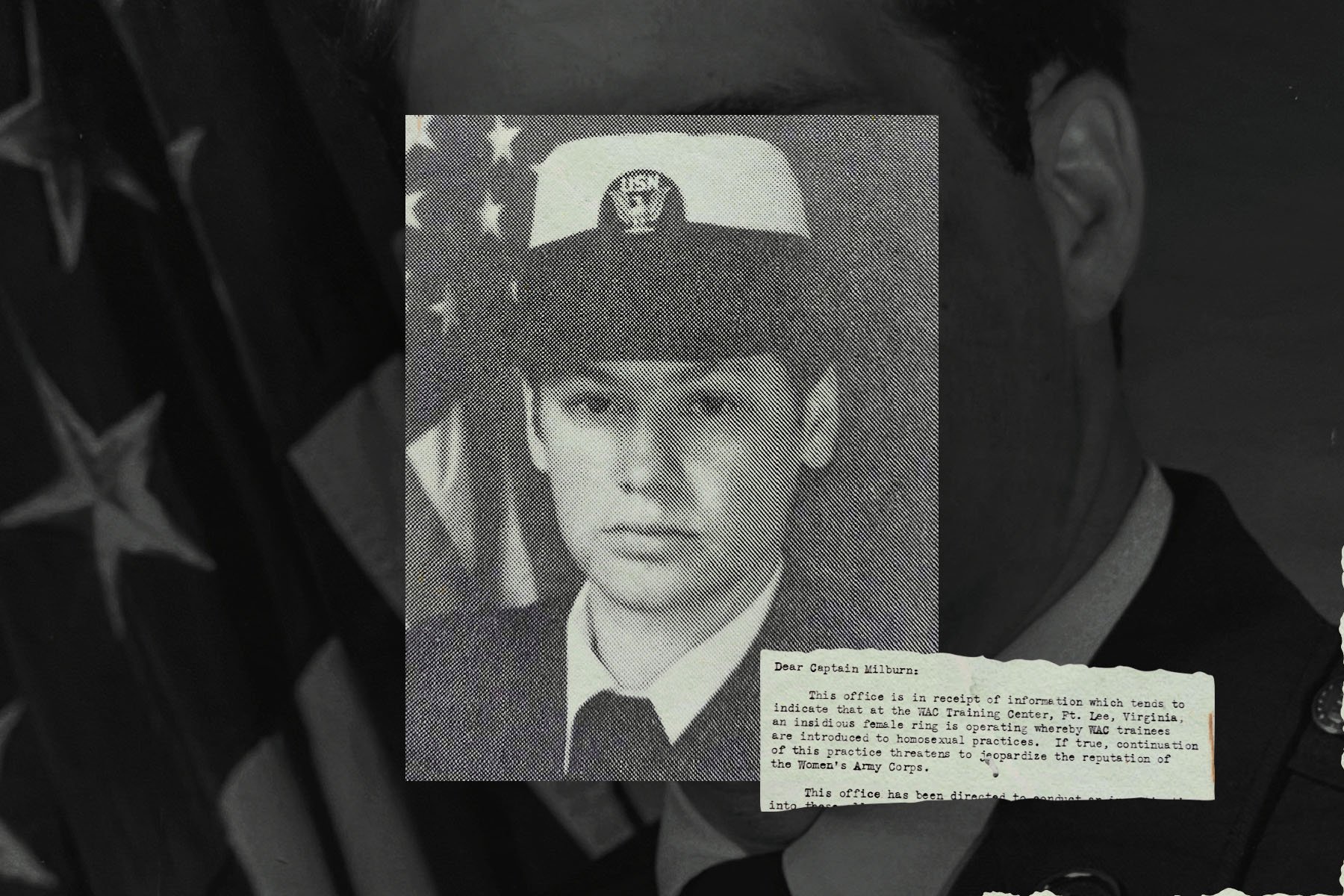

In December 1989, Elaine Rodriguez joined the Navy, following in the footsteps of her Navy veteran father and her older brother, a Marine.

She was 23 when she left her hometown of Jacksonville, Florida, to begin boot camp in Orlando, Florida.

In her official boot camp photo, she appears so serious that she almost scowls. The military’s strict rules, she says, were “a shock to the system.” But she endured—“I’m not a quitter”—only landing in trouble once for giggling with a friend during physical training.

When boot camp graduation day finally arrived, her family came to Orlando to celebrate. Rodriguez’s father beamed in the family photos. It was the proudest Rodriguez had ever seen him. From Orlando, Rodriguez went to Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois to train as an electrician’s mate.

Having grown up in a protective, Catholic, Puerto Rican family, Rodriguez was on her own in the Navy for the first time and loved the independence. “I was doing my own thing,” she says. “I was happy. I guess I could compare it to going to college but getting paid.”

She made friends easily. She studied when she had to and stayed out late at bars when she wanted. Before the military, she had imagined that at some point, she’d find a husband and have kids.

In Great Lakes, away from her home state of Florida, unexpected feelings found the space to emerge. “Am I gay?” she’d wonder.

Origins of the military’s witch hunts

When VanCantfort gets going on his military career, he’s a fast talker, and on a humid September day in Washington, D.C., he’s a conveyor belt of memories. He starts in the early ’80s when he was a military dog handler (13 dogs, many bites) and winds up in Germany and then Greece during the first Gulf War when he’s helping secure military facilities and receiving slaps on the wrist for his hard-charging, eff-the-bureaucracy-and-get-it-done attitude.

His tales, however, lose color and momentum when the era of “anti-gay stuff” in San Antonio surfaces. His manner becomes careful, even procedural. The ’80s were the era of the new AIDS epidemic and a conservative, Reagan-era Defense Department. In 1981, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger made discharge mandatory for gay service members, solidifying a practice that had already been established but was inconsistent among the branches.

The military’s anti-gay policy dates back to World War I’s Articles of War, which implemented a ban that prohibited gay sex. And in 1951, the Uniform Code of Military Justice outlawed sodomy with Article 125—a ban on oral and anal sex—which resulted in gay and lesbian service members being pushed out and occasionally prosecuted. It’s unclear how many gay service members were court-martialed, and in September, The War Horse filed a lawsuit to compel the branches to turn over those records.

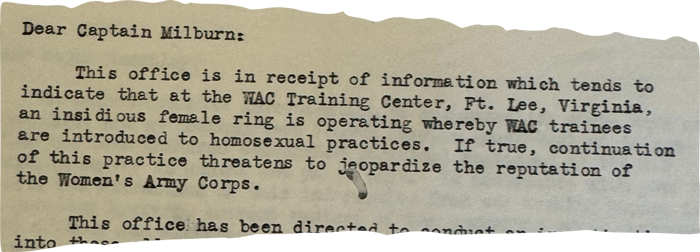

In the years after World War II, the military sought to expel some of the hundreds of thousands of women who had enlisted as part of The Women’s Army Corps or WAC (originally the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps or WAAC) and the term “witch hunt” emerged.

Details of a few of those witch hunts are spelled out in formerly classified documents from 1950-1951 that The War Horse learned had been anonymously surrendered to a museum in Hawaii.

In a December 1950 memo, for instance, a military investigator focuses on an “insidious female ring” that military leaders believed was introducing homosexuality to new WAC trainees at Fort Lee, Virginia. “The homosexual road is not only down, it is always a continuous road from the first homosexual act to the end of the road—the brutal sex crime,” a different investigator later wrote.

A “modus operandi” document described how investigators compiled allegations and rumors, secured and maintained an informant system, inspected mail, and interrogated and polygraph-tested women in the ranks.

Women soldiers admitted under interrogation to letting loose just like their male counterparts—drunken nights, parties. A few reported suspicions of certain women being “that way.” Others reported that they had witnessed women “petting” or kissing or involved in a “lovers quarrel.”

Nobody got off easy. In a document that included notes from a meeting between an Army colonel and a general, a colonel wrote: The Army would “build a case against the guilty that will STICK.”

Sticky note waiting on her door

Within a year of enlisting, Rodriguez was on track to become an electrician’s mate. One afternoon, right before Labor Day weekend in 1990, she was heading to a night class when a lieutenant commander came into a common area of the barracks with an order: If the women knew of any homosexual activity, they better report it.

This visit came a few years after a notorious witch hunt involving Marines at Parris Island. Almost half of the 246 women in a unit were questioned. Sixty-five of them subsequently were pushed out of the Marines.

But Rodriguez wasn’t too worried. She wasn’t going to “narc” on anyone. A few weeks passed and she assumed the whole thing would blow over.

However, one night, when she returned from a class, she was told she had to go to the Navy’s on-base legal department. A stern superior in uniform was waiting for her. He grilled her about alleged homosexual activity that he had heard about.

“He said, ‘This isn’t a witch hunt,’” Rodriguez recalls. “And in my mind, I said, ‘Well, I didn’t say it was. So it must be.’” It was the first time she had ever even heard that phrase.

Rodriguez denied going out to gay bars and being attracted to women, and he let her go. She put the ordeal behind her and looked forward to shipping out to her first duty station in Hawaii.

A few weeks later, though, a sticky note on her door told her to go to the Naval Investigative Service. She headed to the NIS building. The walk was short, but dread warped time into a long and withering few minutes.

When she got there, two Naval investigators knew everything. Her girlfriend? A civilian named Marty. Her favorite gay bar? River’s Edge. Overwhelmed and crying, Rodriguez confessed.

“I was in shock. The only thing that had ever happened to me prior to this was a speeding ticket,” she says. “I literally felt like a criminal.”

The Navy kicked her out with an other than honorable discharge—a common practice that not only marred the records of thousands of service members but denied them access to veterans benefits such as health care and the G.I. Bill. Rodriguez’s commander wrote in her exit paperwork that her behavior “is not compatible with the lifestyle of a service member and will not be tolerated.” The governing body that determines whether a servicemember deserves being kicked out, decided she had committed a serious offense. And with that, the Navy emptied out her plan for the future.

Silence proves the safest bet

Rodriguez isn’t sure how investigators gathered intimate details about her. This was before cell phones and social media. She suspects either someone in her unit ratted her out or someone spotted her at River’s Edge, the gay club outside Chicago.

VanCantfort knows that both scenarios are probable. In the early 1980s, in San Antonio, the Armed Forces disciplinary control board would create the list of bars he and his fellow officers had to scope out on weekends.

He also remembers times when service members who were in trouble would offer intel (with or without evidence) on gays and lesbians in uniform in exchange for a lighter punishment.

“It creates a whole class of people that are victimized with no way to get help,” he says, “because the system is so secured against them.”

It’s why gay people in the military lived quiet, closeted lives, the sword of Damocles hanging above them should they share the truth even with close friends. In a system built entirely on power imbalance, silence proved the safest bet.

VanCantfort said he learned all of this a few months into his enlistment at 19 years old.

One night after a barracks party, with a few beers in him, he crawled into bed. At some point, he stirred awake and found someone standing in the dark beside his bed. The man, who VanCantfort recognized as living in the barracks, was naked.

Shocked, VanCantfort recalls stammering—How did you get in my room? Get the fuck out.

He had honed scrappy fighting skills as a kid growing up poor in Texas and Massachusetts. He attended a dozen schools and didn’t flinch at throwing a punch or insult to defend himself.

As the man moved toward the bed, VanCantfort said he fought him off. For weeks, though, the man taunted VanCantfort, daring him to report the attempted assault. “Making sure I understood, he would flip the story and claim I was a ‘fag’ and was trying to hit on him,” VanCantfort recalls. So he stayed quiet.

A couple of years later, as an armed forces police officer engaging in witch hunts, VanCantfort stepped into a role that gave him all the power.

Little changes under ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’

After Rodriguez learned in late 1990 that she was getting kicked out with an other than honorable discharge, the news spread around Great Lakes. Stares and slurs followed her for the 45 days it took to process her discharge. Sailors taunted her with catcalls. “Take her out back,” they’d say. She was assigned to clean the barracks.

One day, a female sailor in the barracks called out—“Rodriguez!”—and demanded that she repair something in her room. Rodriguez walked in, and the woman shut the door and sexually assaulted her.

Rodriguez never told anyone. Who would believe her?

Homophobia was rampant in the early 90s and continued into the “don’t ask, don’t tell” era, which ended in 2011. President Obama repealed the policy, which was intended as a compromise to an outright ban on gays in uniform, allowing them to serve as long as they kept it hidden. Witch hunts slowed, but did not disappear.

Since then, the Pentagon has invited gay and lesbian service members who were discriminated against to apply for a discharge upgrade, an often cumbersome process that only about 1,700 service members have pursued, according to the Defense Department. Most have received an upgrade.

In October, the Pentagon announced that it had identified 820 veterans who were kicked out of the military because of their sexual orientation under “don’t ask, don’t tell,” and that those veterans would now receive honorable discharges.

And over the summer, President Biden announced pardons for gay and lesbian veterans who were convicted in a military court for consensual sex. But as The War Horse has reported, the narrow confines of the pardon exclude thousands of gay and lesbian veterans who were forced out of the military but didn’t wind up in court. As of November, only 14 veterans had applied.

Dixon Osburn, an attorney who helped orchestrate the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” in 2011 supports all this federal action, but says gay service members who were kicked out in the ’90s and earlier, like Rodriguez, often don’t have records that clearly indicate the true nature of their dismissal from the military.

This leaves the Department of Defense with a tricky choice. “Are you just going to carte blanche, get rid of all the derogatory records, because the system is so flawed?” Osburn says. “That might be the easiest thing to do, but the military, I think, is trying to be exacting and making sure that they don’t overturn appropriately recorded bad conduct.”

Osburn and other advocates don’t know what to expect from President-elect Trump when it comes to reparations for veterans kicked out of the military because of their sexual orientation.

Hegseth provided some clues during an interview that aired just two days after the election on The Shawn Ryan Show, a podcast hosted by a former Navy SEAL and CIA contractor. “The dumbest phrase on planet Earth in the military is our diversity is our strength,” Hegseth said, pumping his book The War on Warriors.

He lamented the military’s slide into wokeness, beginning, he said, under President “Clinton with the tinkering of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’” and really accelerating, he said, under President Obama. He talked about frequent conversations with veterans and active-duty service members complaining that “standards are dropping, the woke stuff is everywhere,” and telling him, “I feel like I’m walking on eggshells.”

About a week later, Trump announced he was tapping Hegseth to lead the military. But as controversy swirls around Hegseth’s character, reports surfaced Wednesday that Trump is considering another veteran with a well-established track record of policies decried by the LGBTQ communities: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

‘Didn’t want to be gay’

According to Department of Defense statistics, a majority of gay and lesbian servicemembers who were kicked out before 2011 were quietly discharged with an honorable or general discharge.

Rodriguez wasn’t as lucky.

After the Navy booted her with an other than honorable discharge, she returned home to Jacksonville and lied to her family, telling them a fistfight led to her dismissal. “I didn’t want to be gay,” she says. “I started dating a guy. I would hide my paperwork, my DD 214, and everything, I would hide it under my mattress.”

She tried to become a detective. But a police academy wouldn’t accept her because of the “commission of a serious offense” on her record. She eventually got work at a medical supply company, which she’s grateful for, but it’s not the career she wanted. She also, eventually, confessed to her family that she was gay, and that’s the reason the Navy disposed of her.

For three decades she largely kept her past military service to herself, ashamed of her short time in uniform and her unceremonious exit. About 21 years ago, though, at the urging of her family, she decided she’d try to get her discharge upgraded. Military review boards denied her upgrade application three times for various reasons, including her admission of lying all those years ago. But with the help of a lawyer, earlier this year Rodriguez finally received an honorable discharge.

“It’s bittersweet,” she says.

Her parents have died, and she can’t share her victory with them. Rodriguez turned 58 in November. Her childhood dream of becoming a cop after religiously watching the tough New York female officers on Cagney and Lacey is long gone.

In the last two years, her fight to get that honorable discharge has revived old memories she thought she had wiped away, like the sexual assault. In the last year, she has had trouble falling asleep. She started relying on alcohol to doze off and is now on medication to cut that craving.

In the middle of the night, her wife will occasionally find her in the fetal position with blankets over her head.

“I don’t like to say they screwed up my life,” Rodriguez says, referring to the Navy. “But they screwed up my life.”

What’s next after Trump’s victory?

Rodriguez and VanCantfort have never met. But when The War Horse told her about the former military police officer who participated in witch hunts, she was taken aback. Why would he do it? She wondered.

“I just can’t even imagine having that type of job,” Rodriguez said. “I actually feel bad for him.”

At the time, VanCantfort was young and following orders. Even back then, he said, he disagreed, but disobeying was not an option.

“That’s insubordination,” he says. “And that’s grounds for getting kicked out of AFPD [Armed Forces Police Department] as well as not getting any other good assignments.”

After a year with the San Antonio Armed Forces Police, VanCantfort left the witch hunts behind for a new assignment. He ascended in the military, eventually retiring as a master sergeant. His license plate reads “USAF 23,” honoring the 23 years he spent in the Air Force. And outside of the military, he compiled nearly two decades as a cop and intelligence expert.

VanCantfort, 61, is not a big feelings guy and speaks matter-of-factly. When asked how he believes a Trump presidency will impact a “woke,” more inclusive service, he offers a belief he repeats often: Anyone who is mentally and physically fit to commit themselves to their country should have the chance. And the military should stick to being nonpartisan.

The Trump transition team did not respond to questions about whether the new administration plans to keep Biden’s pardons for convicted gay veterans intact, or eliminate policies it considers “woke.” It also failed to respond on whether the Trump White House will reinstate a ban on trans servicemembers enlisting. According to a recent Newsweek article no decision has been made on a potential trans ban.

On the day after Trump’s victory, Rodriguez decided to display her honorable discharge for the first time on Facebook. In the post, she congratulated Trump voters while thanking Presidents Biden and Obama for trying to right the wrongs of the past. “If it weren’t for them, I would not be getting what I deserve as well as many others,” she wrote.

Some of her Trump-voting friends liked the post, and perhaps that should’ve heartened her that the chorus of anti-woke talk will soften now that the election is over.

She can’t help but worry, though, for one of her male cousins who is in the Army and married to a man. And when her wife wants to hold her hand or kiss in public, she still looks around, paranoid, worried that the affection is somehow wrong. Something to be punished.

This War Horse investigation was reported by Anne Marshall-Chalmers, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.