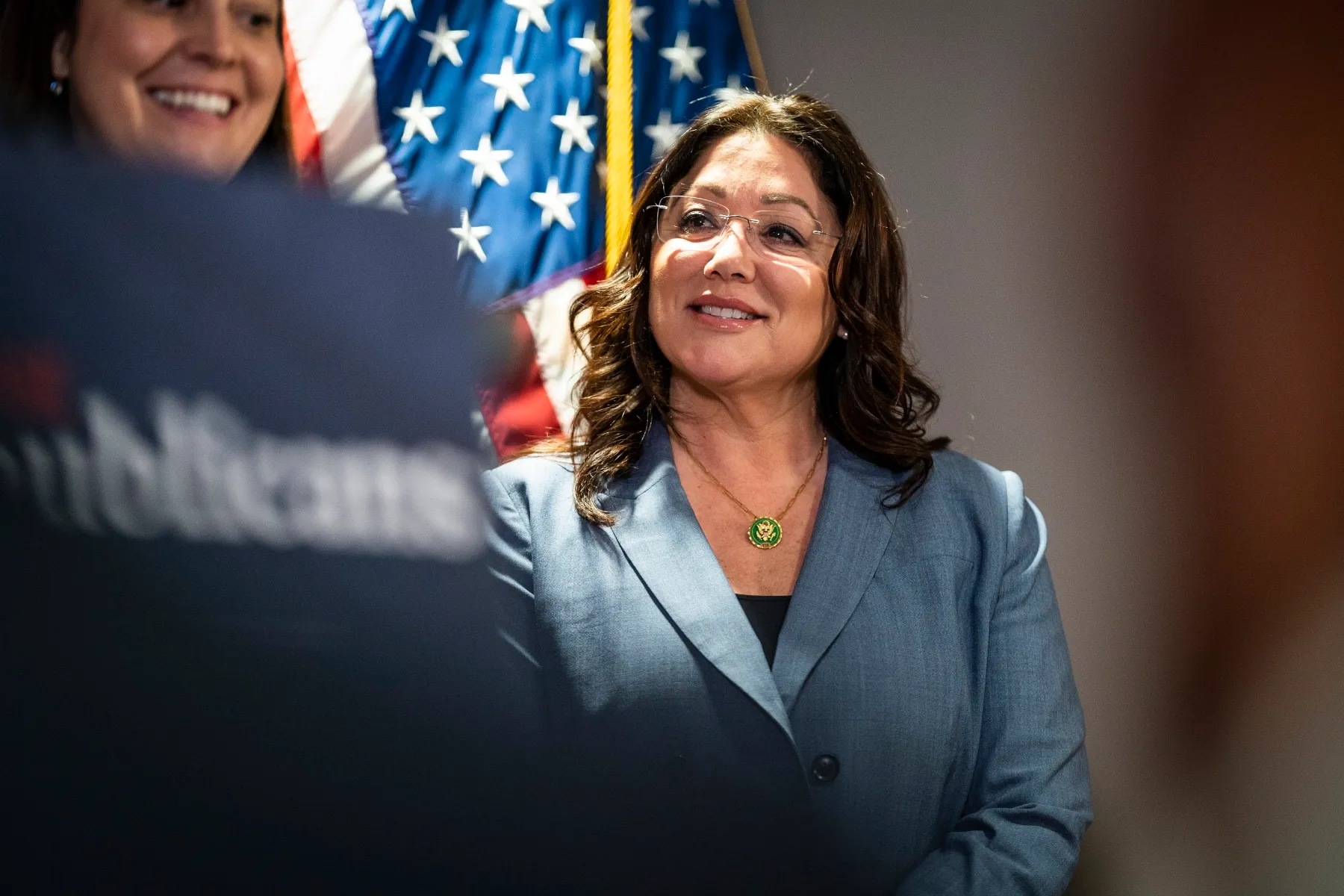

President-elect Donald Trump has chosen Lori Chavez-DeRemer, one of most pro-union Republicans to recently serve in Congress, to be his Labor secretary.

Chavez-DeRemer lost her reelection bid to represent Oregon in the House by a narrow margin. Her campaign was backed by about two dozen unions, including those representing flight attendants and grocery store workers.

Sean O’Brien, the president of the influential International Brotherhood of Teamsters union, pushed for Chavez-DeRemer’s nomination.

In Congress, she was one of three House Republicans to support the PRO Act, one of the most substantial union bills in recent years that would strengthen workers’ rights to organize and limit retaliation from employers. She was also one of the few House Republicans to support the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act, which would expand collective bargaining rights for state and local government workers — positions predominately held by women.

Chavez-DeRemer has advocated for improvements to the child care system. Last year, she was one of only five Republicans who responded to The 19th’s questions about the kind of child care policy they’d support, saying she was in favor of expanding a tax credit for employers who offer child care.

She has spoken about the importance of the Republican party being the party of workers “with President Trump leading the way.”

“Lori has worked tirelessly with both Business and Labor to build America’s workforce, and support the hardworking men and women of America,” Trump wrote on Truth Social, his social media platform.

On X, O’Brien, of the Teamsters union, thanked Trump for “putting American workers first” with Chavez-DeRemer’s nomination.

“Nearly a year ago, you joined us for a Teamsters roundtable and pledged to listen to workers and find common ground to protect and respect labor in America. You put words into action. Now let’s grow wages and improve working conditions nationwide,” O’Brien wrote.

If confirmed, Chavez-DeRemer would follow Biden’s first Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, a longtime union leader, and acting Labor Secretary Julie Su — the former California labor secretary and commissioner, as well as a former labor attorney — in the role.

The pick represents something of a break for Trump, who has typically chosen pro-business leaders to head the department.

Now the question is how Trump’s approach could evolve with Chavez-DeRemer at the helm.

It was expected that Trump’s Labor Department would undo some regulations from past administrations. Likely on the chopping block is an Obama-era overtime rule that administrations have been fighting over ever since.

During the Obama administration, the Department of Labor expanded the number of workers eligible for 1.5 times pay if they work more than 40 hours a week to those earning up to about $47,000 a year — about 33 percent of people, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank that focuses on the needs of low- and middle-income workers.

But the rule was blocked in court, and when Trump took office, his Department of Labor proposed a new rule with a lower threshold at about $35,500, gutting the impact. About 8 million workers — 4.2 million women, 2.9 million people of color, 2.7 million parents — were cut out as a result.

The Biden administration then pushed back, raising the threshold back to those earning up to about $43,800. An estimated 4.3 million workers, more than half of whom are women, were impacted. A Trump-appointed federal judge in Texas recently blocked that expansion, teeing up Trump’s Labor Department to take over from there. The threshold is set to go up again to $58,656 in 2025.

During the president-elect’s first term, the department also rolled back the Fair Pay and Safe Workplaces executive order issued during the Obama administration that required federal contractors to comply with 14 labor and civil rights laws, including a paycheck transparency rule. Biden issued a new rule last year that bars more than 80 federal agencies from considering workers’ current or past pay in setting their salaries, a practice that has suppressed wages for women by carrying inequities from one job to the next and one that is considered key to closing the pay gap between men and women.

It’s likely the Trump administration will want to revisit those policies again.