When Vanessa Lynch learned that a fracking well pad would sit right next to the park where her two kids used to play soccer, she began to research potential health hazards. The more she learned, the more alarmed she became.

Though it is most commonly discussed as a climate change contributor, fracking is also linked to a host of health issues, including an increase in childhood asthma, childhood cancers and adverse birth outcomes.

“To know that area, which had been such a huge part of my children’s childhood, was now going to be a place where local community members would be exposed to the pollution coming from oil and gas — that was upsetting,” she said.

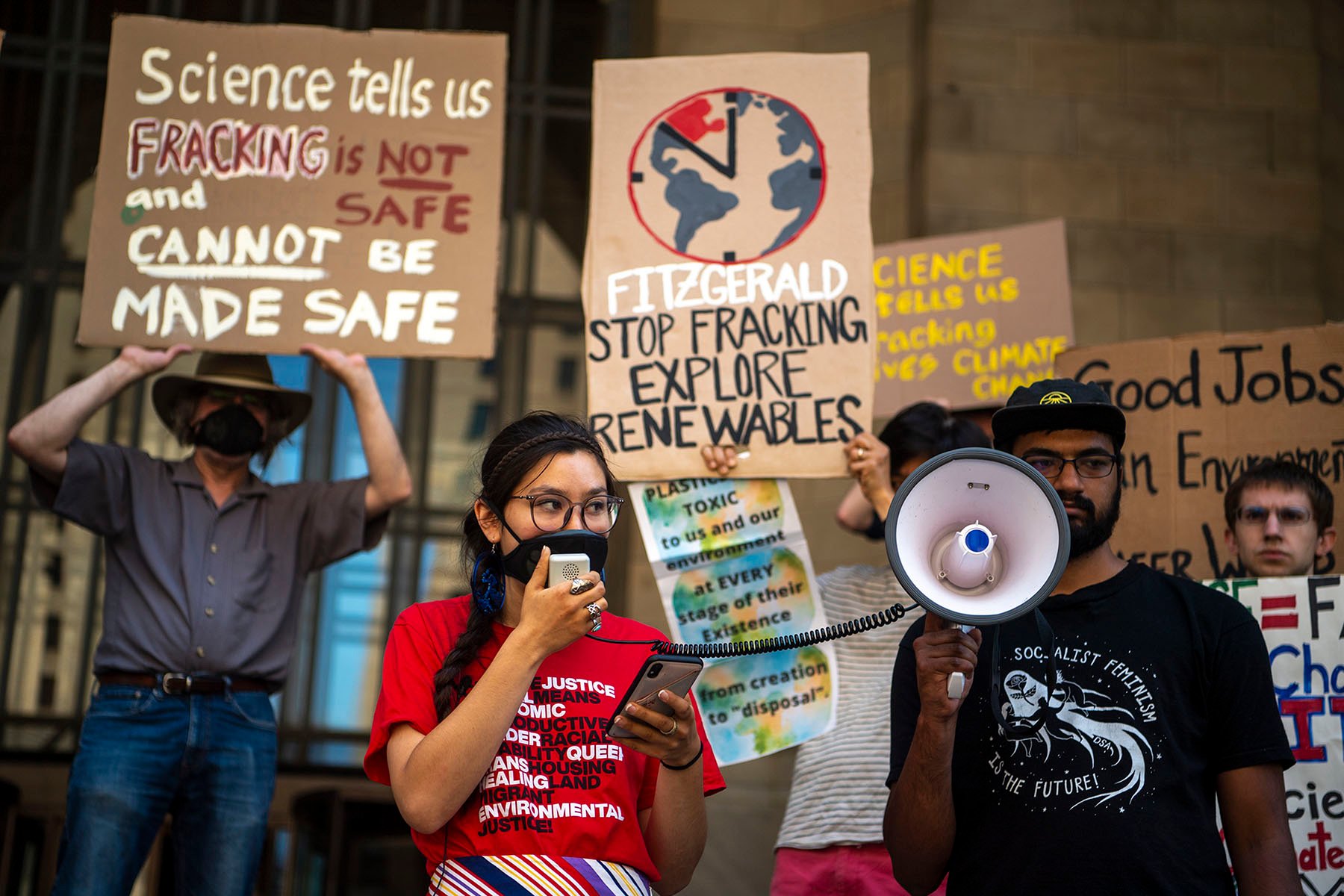

So in 2017, Lynch began organizing with other residents to prevent more wells from being placed in Indiana Township, Pennsylvania, east of Pittsburgh. Eventually she joined Moms Clean Air Force, an environmental advocacy group, as a field organizer working to share information about the health harms associated with industrial fracking and pushing policy that can regulate the industry.

“Learning about how much this impacts regular people was really the starting place for me of the work that I’ve done,” Lynch said.

Nearly 1.5 million Pennsylvanians live within a half mile of fracking infrastructure, and a majority of people in the state support more regulations on the practice. Fracking involves injecting a mix of water, sand and chemicals, including benzene, a known carcinogen, into the ground at a high pressure to release methane gas. In one recent poll by the nonprofit Ohio River Valley Institute, 94 percent of respondents supported mandatory disclosure of chemicals that are used by companies that frack and 90 percent support increasing the distance between well pads and schools and hospitals.

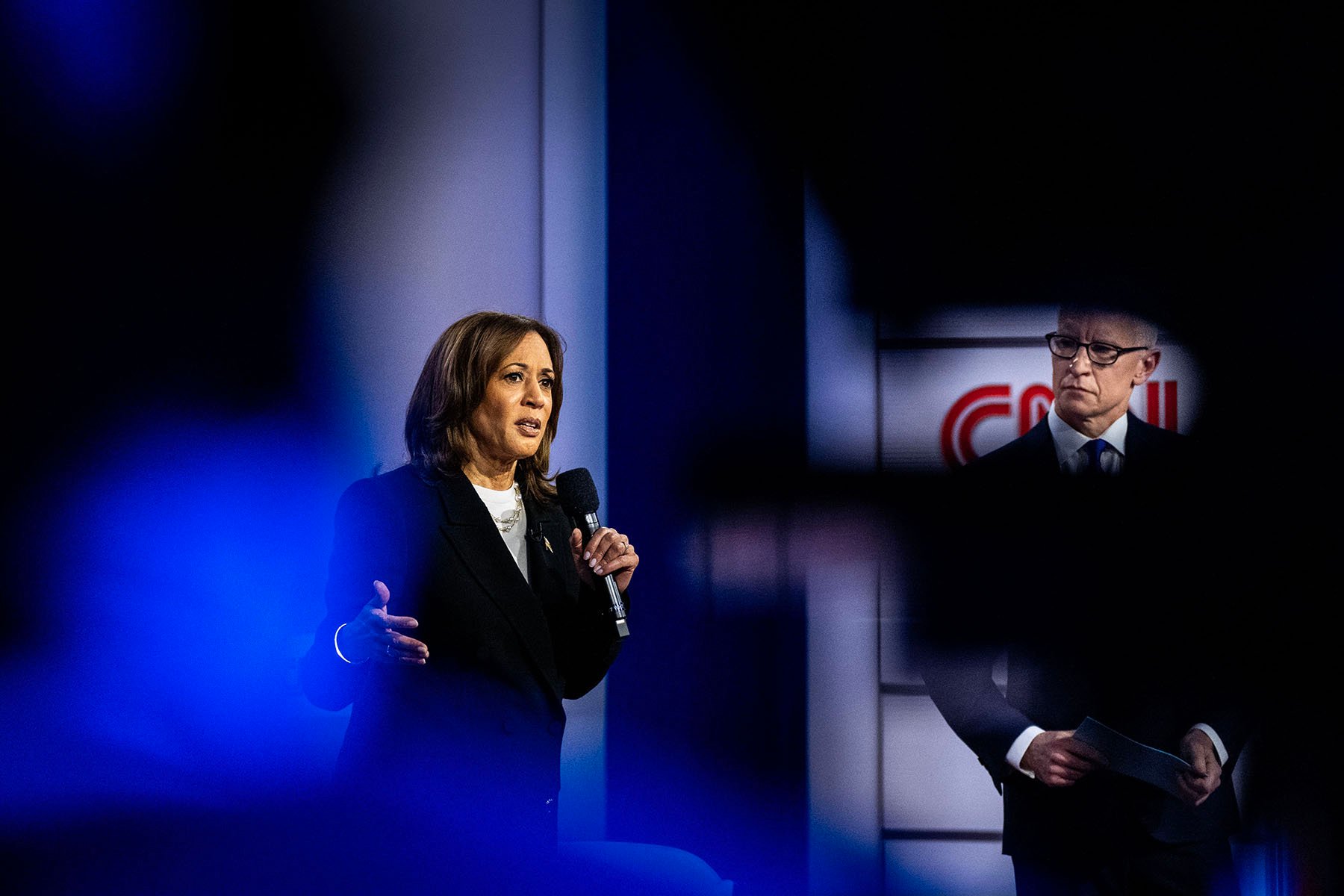

But even this late in this election season, neither presidential candidate has discussed fracking in a way that significantly addresses the public health issues that Lynch and so many others are fighting to be taken seriously. In this campaign, Donald Trump has pledged to cut red tape for oil and gas industries, including regulations that protect the public from pollution. Kamala Harris, who as a candidate in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary said she would ban fracking nationally, has shifted her position during her current bid. Her stance has been less focused on reducing oil and gas production and more on increasing renewable energy. As she recently stated in a CNN town hall in Philadelphia, “I know we can invest in a clean-energy economy and still not ban fracking.”

In Pennsylvania, a swing state where pro-fracking rhetoric is aimed at getting out the vote, the issue is talked about in the context of the economy and job creation — the state is the second largest producer of natural gas after Texas. But most of the land being fracked is private, meaning it wouldn’t be subject to a federal ban even if Harris were to bring it back up. Instead, activists say the campaign talk over a fracking ban is obscuring real health concerns of residents.

“It’s framed as a political issue when really it should be framed as a public health issue. We all want to be healthy. We all want to have clean water and clean air. We all want to have strong economies,” said Shannon Smith with FracTracker Alliance, a Pennsylvania-based advocacy group that tracks fracking infrastructure across the country. “I wish that we had political leadership and the political will to protect people from the impacts of fracking, but on a national scale, we just haven’t seen that.”

The public health stakes are high. There are dozens of studies that have examined the impact fracking has on human health, according to Ned Ketyer, a retired pediatrician and president of the Pennsylvania chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility. One from 2022 found that pregnant people within 6 miles of a fracked gas well had an increased risk of having a baby born at a low birth weight or preterm. Other studies have linked fracking to issues with fetal development, including babies being born with congenital heart defects. Pregnant people are also at higher risk of developing preeclampsia, high blood pressure that can be a dangerous pregnancy complication, if they live near a fracked gas well.

Other research showed higher rates of childhood cancer near fracking infrastructure, including a 2022 study that found an increase in leukemia among children in Pennsylvania who lived near a fracking well.

“The people who are most impacted by the pollution and the waste from fracking appear to be women and children, especially pregnant women,” Ketyer said. “That’s not surprising. That’s what you see with any environmental health risk.”

Beyond the health risks, fracking is also a major contributor to greenhouse gasses, which are causing the climate crisis. Ketyer put it bluntly: “Supporting fracking is climate denialism.” So he was disappointed to see Harris change her stance on fracking. But, he added, “I do try to see the bigger picture, right? And there are other things, most other things [with Harris], in fact, that I think will be improvements, that will help improve public health, improve the health of the environment.”

Public health is what he and groups like Moms Clean Air Force and Fractracker Alliance aim to educate the public about through their field organizing, data collection and public testimony at town halls and legislative hearings. But even in the state it’s been difficult to create change. Activists say the oil and gas industry has a significant hold on politics and point to Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro as an example. When he was attorney general, he convened a statewide grand jury to look at the evidence that linked fracking to health issues as part of a bigger effort to hold the industry accountable. But once elected as governor, he built relationships with the industry. It felt like a betrayal to activists like Smith and Keyter.

“In Pennsylvania, most of the politicians support fracking,” Keyter said. “The thing that is problematic is that the senators, the legislators, Gov. Shapiro, they all know that fracking hurts people.” He added: “[Shapiro’s] seen the evidence. He’s heard the witnesses. He’s listened to the testimony. He knows how people have been impacted.”

While Harris has been somewhat quiet on her environmental agenda in her bid for the Oval Office, many environmental and climate justice activists are optimistic that she’ll continue the work of the Biden administration to transition the nation away from fossil fuels and protect the public from pollution. Under President Joe Biden, the Environmental Protection Agency finalized rules to reduce toxic air pollution emitted from chemical plants and put more protections in place against harmful chemicals like benzene. The rule also required companies to monitor for these hazardous chemicals and make the data publicly available. In addition, the administration has made environmental justice a key priority and has directed funding to communities that have been disproportionately harmed by polluting industries.

In contrast, Trump rolled back over 100 environmental regulations during his first term and has signaled he intends to roll back regulations again if reelected. He also tapped a climate denier, Scott Pruitt, to lead the EPA and directed the agency to delete the website’s section on climate change. He withdrew the country from the Paris Climate Agreement, a global commitment to lower carbon emissions.

“It’s only going to be worse if he’s elected. And it’s not because I’m saying so. It’s because he said so,” Ketyer said.

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, the conservative playbook for how to run the country if Trump is elected, takes aim at the federal authority of the EPA. The chapter on the agency, written by a former Trump EPA official, outlines a plan to limit the scope of the agency and its focus on climate change. Trump has tried to distance himself from the playbook, but he has deep ties to the authors.

The EPA already took a hit during Trump’s first term in office when over 1,600 scientists and policy experts fled the agency under his administration. Now, Tracey Woodruff, a former EPA policy adviser and a researcher at the Center of Reproductive Health at the University of California, San Francisco, said that another Trump term could result in dire consequences for public health if regulations like the Clean Air Act or Clean Water Act are weakened.

The results could be fatal, she said.

“Just look at abortion. You have an increase in infant mortality and women dying,” she said. “So it’s not apocalyptic or whatever, to say that people will die because they roll back regulations and squash things that are evidence-based and science-based, it is not hard to imagine that people will die.”

For groups like Moms Clean Air Force that run get-out-the-vote efforts, Lynch urges voters to think about the health of their families. “We just encourage moms to vote with their children in mind,” she said. “That’s really the center of who we are as moms, and the center of how we hope moms think about the future.”