Ahead of the November 5 presidential election, more than 70 million people have cast a ballot during an early voting period that in some instances has included record turnout.

But access to the ballot remains a challenge for some voters.

In recent years, the courts have rolled back voter protections in decisions that advocacy groups say have allowed anti-voting policies to flourish. Republican lawmakers in some instances have restricted vote-by-mail and enacted more strict voter identification laws. In almost half the country, voters are expected to face new voting restrictions since the 2020 election, according to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice.

Americans are also dealing with a rise in disinformation about voting — whether through phone scams, fake videos created by foreign adversaries or online platforms.

Advocates say among those most disproportionately impacted are voters of color, rural voters and those with disabilities — and that’s the reality even without a deadly hurricane or rampant politically motivated gerrymandering.

The 19th set out to capture the stories of some of those who face voting barriers. Four photographers spoke with voters — from the storm-ravaged Appalachian counties of North Carolina to volunteers driving people with disabilities to the polls in Georgia. Photographers also followed residents of Philadelphia and Atlanta as they rallied at get-out-the-vote events. While some reported having had improved access to voting, others acknowledged various struggles they feared would make voting much harder this year.

Voting through the wreckage of Hurricane Helene – Buncombe County, North Carolina

Residents like Melanie Reising face treacherous drives and FEMA tents as polling locations, but they’re unwilling to let disaster silence their voices.

At first we were like, ‘Where are we supposed to vote?”

Melanie Reising

After Hurricane Helene raged across the Southeast, killing more than 200 people and causing an estimated $53 billion in damage in North Carolina alone, residents of the state were worried they might have difficulty voting in the presidential election. Unstable roads, destroyed buildings and election worker vacancies forced officials to change planned polling locations and go as far as erecting a FEMA tent for voting.

Melanie Reising, a 65-year-old who lives in rural Buncombe County, said she would normally vote at the Garren Creek Fire Department. When the roads to her usual polling location became impassable, she changed plans and decided to vote early at the Black Mountain Library despite her fear of driving on the damaged roads that would get her there. Reising said she’s motivated by a need to cast her vote this year. Some of the issues that are most important to her are women’s rights and teachers’ salaries.

Also in Buncombe County, Martha Calderón, 64, said she will have to walk to her polling place if she even finds the time to vote this year, as her family struggles without electricity or running water in their storm-damaged home.

As a naturalized citizen who immigrated from Latin America, Calderón feels that having the right paperwork in hand is her guarantee to accessing the ballot. She has her driver’s license and passport, but every other document was lost to the flood.

(Justin Cook for The 19th)

Despite the various difficulties Calderón is experiencing this election, she said voting is a duty and has high hopes that whoever gets elected president will help Latin American immigrants like herself. “There are many hard-working people who have been living in this country without papers for many years. What I’d hope for the new president is to help them,” she said.

Rolling to the polls: when mobility is an obstacle – Atlanta, Georgia

Volunteer services like Roll 2 the Polls provide a resource for voters using wheelchairs, but some accessibility needs are limited by recently enacted voting laws.

Every year they tell you ‘this is the most important election of your life.’ … I’m afraid this year it really is.”

Elizabeth Huhn

A 2022 survey by the U.S. Election Assistance Committee found that 1 in 7 voters with disabilities experienced difficulty casting their vote in the midterm elections. Efforts like the Roll 2 the Polls van service in Atlanta offer some relief for those with mobility issues, but other disability needs can be more difficult to address. Elizabeth Huhn, now a driver with the grassroots nonprofit Georgia ADAPT, which runs Roll 2 the Polls, lived with chronic pain and fatigue for years after surviving cancer. She said there are many barriers to voting that can arise even after voters have reached their polling location, especially for people with disabilities.

(Nicole Craine for The 19th)

“In years previous, there were long lines and it’s really hard to wait an hour, but we had to wait five hours to vote,” she said. Huhn said it’s especially tough now that a Georgia law added restrictions on handing out water or food to people waiting in those long lines to vote.

“You know, every year they tell you ‘this is the most important election of your life.’ And, you know, every year it usually is, but I’m afraid this year it really is, and I personally have my feelings, which I keep to myself, but it’s just there’s a really stark difference. There’s a much larger difference between these two candidates than normal,” she said.

Cathy Johnston, who uses a wheelchair and the Roll 2 the Polls van service, said she was excited to vote this year because there’s a woman running for president. Johnston acknowledges that lines at the polls have gotten better in recent years. She also has had relatively little difficulty voting. “Even when there were long lines, they would move me to the front of the line. They also have machines that are lower, so if you’re handicapped, you don’t have to try to reach up. They have several side by side. So, I’ve never had a problem.”

Battling bureaucracy – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Last-minute location changes and long routes to the polls have not stopped committed voters like Karlynne Staten.

This was supposed to be our first time voting together as a family. Somehow, their registration went through but mine did not.”

Karlynne Staten

Embracing the right to vote is a family legacy for Philadelphia resident Karlynne Staten: Her great-grandmother, Vivid Apple White, was a key plaintiff in a 2012 lawsuit against discriminatory voter ID laws. This year, Staten was hoping to make voting a family affair with her 19-year-old twins, but a problem with the address on her paperwork has the family split across voting districts. On Election Day, she will have to take four different modes of public transportation and travel for over an hour and a half to reach the polling place in her old neighborhood.

“(My twins) were with me when I voted for Obama when they were babies and this was supposed to be our first time voting together as a family. Somehow, their registration went through but mine did not,” Staten said. Despite the long trek and disappointment of not achieving the imagined family activity of voting together, Staten said nothing will stop her from voting this election.

(Rachel Wisniewski for The 19th)

Jackie Fulton said she was unable to vote early because her polling location changed and she was not notified of the new location. “Usually we vote at the playground on 11th and Oxford and they moved the location. To me, that’s a barrier. … You think you’re going to vote, it’s voting day and I get there and I can’t vote. So that makes a lot of people go home because I don’t know where I’m going, so I can’t vote.”

Fighting misinformation – Atlanta, Georgia

Trained poll monitor Alicia Black Brumfield recognized a phishing attempt disguised as voting support. Digital disinformation campaigns often target voters with less resources.

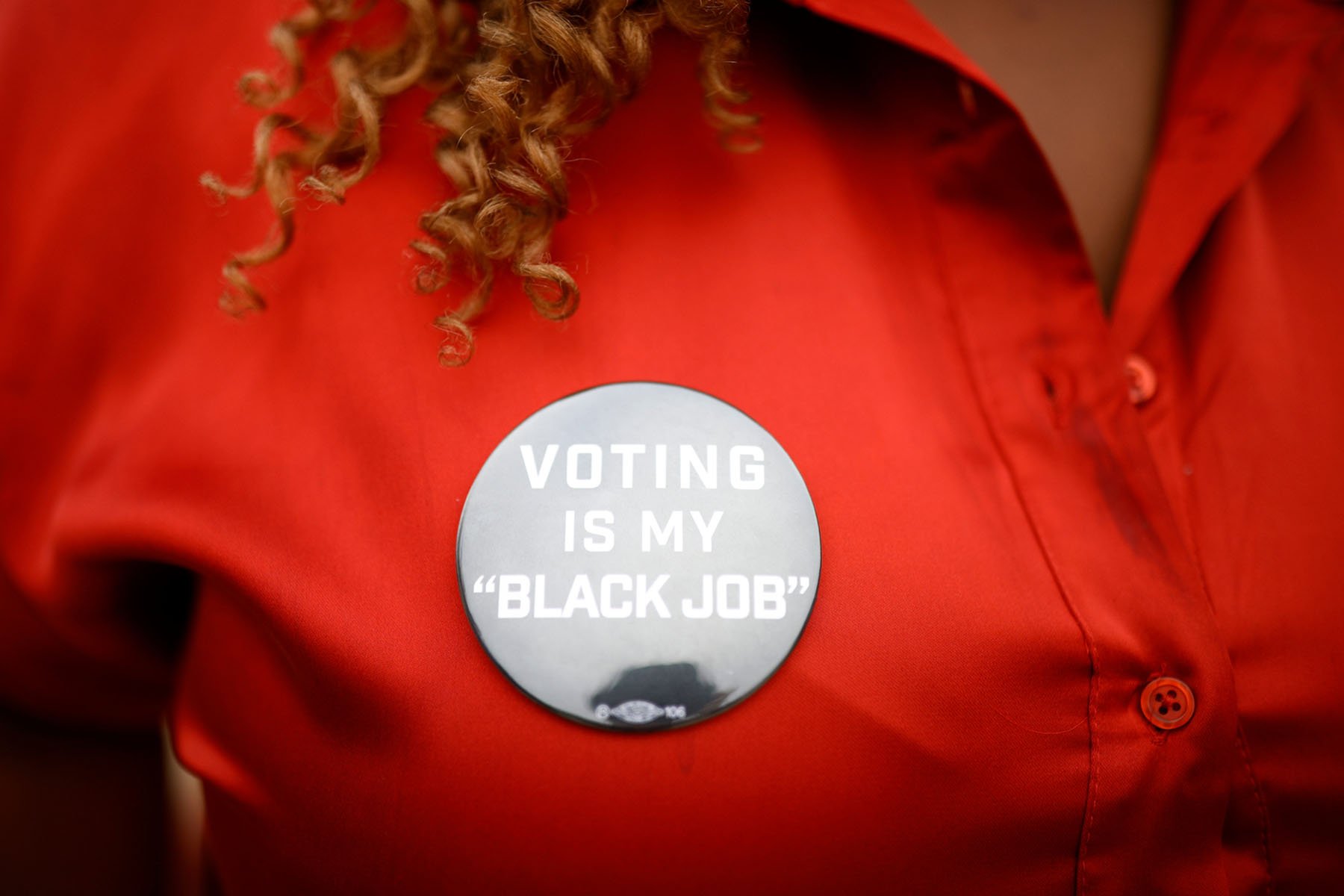

(Melissa Golden for The 19th)

I just want to make sure that democracy remains for all.”

Alicia Black Brumfield

A few months ago, Alicia Black Brumfield experienced a frightening voter misinformation campaign that might also have been a phishing attack. “I received a text that said, ‘Hey, all you have to do is click this link and we’ll take care of the rest. Don’t worry about submitting your vote, don’t do early voting. We can take care of your voting right here.’”

As a registered poll monitor, she knew better than to click on such a suspicious link that asked for personal information and discouraged voting, and she contacted friends and family to alert them that they might receive similar messaging.

“The efforts to dissuade or actually confuse people, that is my biggest fear.” She said she’s been so frightened of how polling locations and other information can change at the last minute that she’s checked her “My Voters” page “like, every single day.”

A few years ago her husband, who had been voting in Fulton County for eight years, had his voter registration challenged. “So it’s little things that have innately happened to me that have caused me to be extra cautious with my voting.”

Justin Cook, Nicole Craine, Melissa Golden, and Rachel Wisniewski contributed reporting.