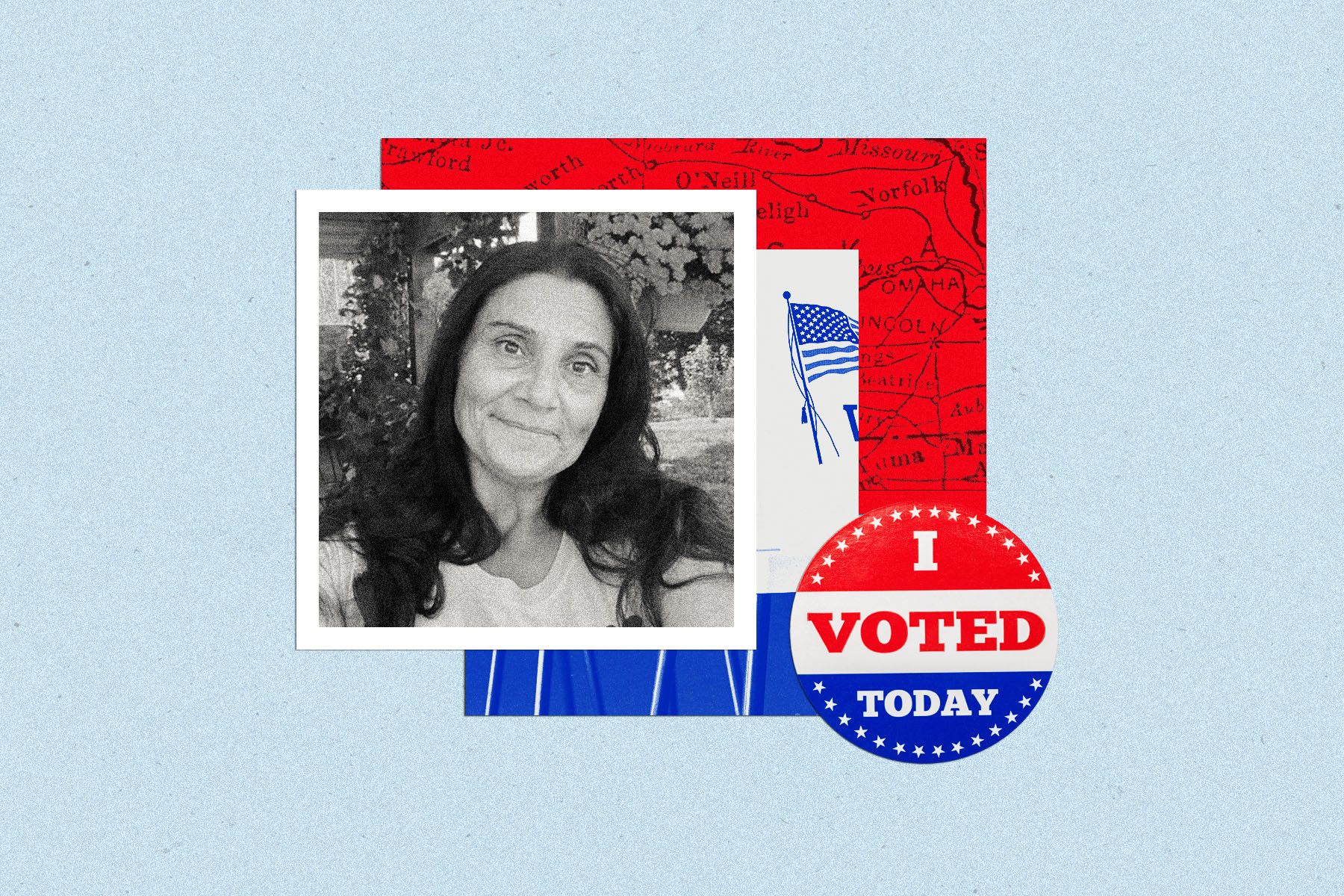

Angela Pluta walked into the visitors’ center at the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation in Omaha, Nebraska, around 10 a.m. last Friday, unsure of what to expect. She was looking for a job and someone at a safe house for formerly incarcerated women, where she has been living, told Pluta that the center had an opening for canvassing work, paying $25 an hour.

She was hired and started training immediately, which opened Pluta to a new world of possibilities. Though she is 49 years old, she had never voted before. Politics and the voting process had felt overwhelming and confusing. Now, here she was, learning about all of the candidates on the ballot, where they stood on the issues and what the wording of each ballot measure meant in a way that actually made sense.

“Before that, I had no idea that there were so many different things and subjects on the ballot that you could vote on,” Pluta told The 19th. “A big part of what stopped me from voting before is, basically, I didn’t feel like I had any business going out there voting because I didn’t follow it enough to be informed to even know what I was voting for.”

Then, the canvassing trainer asked her a question she didn’t expect: “Have you voted yet?”

Pluta answered honestly — “no.” The trainer informed her that if Pluta were interested, the center would cover the transportation cost to get her to a polling place where she could not only register to vote, but also vote early. Pluta needed to decide quickly; the voter registration deadline was that day.

Before she knew it, she was making the 20-minute Uber ride to the Douglas County Election Commission.

Just 10 days earlier, Pluta had been legally barred from voting in Nebraska because of her criminal record. Nebraska is one of 48 states that restricts voting access for people with felony convictions. In 2024, an estimated 4 million U.S. citizens nationwide, representing 1.7 percent of the voting-age population, will be ineligible to vote due to these restrictions, according to a report released by the Sentencing Project last month. Of those, about 764,000 are women.

-

Read Next:

The laws vary by state. Twenty-three states prohibit voting for people while they are physically in prison, according to the Sentencing Project report. Others require people to complete all terms of their sentence, including paying any outstanding fines or fees associated with their crime and incarceration, before they can move to reclaim their voting rights. For nearly 20 years in Nebraska, where Pluta lives, people with felony records had been able to register and vote two years after completing all terms of their sentence, including probation and parole.

This summer, though, Nebraska found itself in the middle of a court battle between voting rights advocates who wanted to remove the two-year restriction and state officials who wanted to keep it in place. On October 16, the Nebraska Supreme Court issued a ruling allowing people with felony records, like Pluta, to vote immediately after completing the terms of their sentence. Others who are still in prison or on probation still cannot vote until those periods are over.

Pluta’s four-year probation ended last year. Without the state’s Supreme Court decision, she would have been ineligible to vote until 2025. Even once she had the ability to vote, though, something held her back, she said.

I guess I could have never anticipated how excited I would be, or how fulfilling it was for me to be able to vote.”

Angela Pluta

“I don’t know how to explain it. It’s like once you get denied the right to something, there are many people who have a negative attitude about it,” she said. “When you get rejected, you’re like, ‘I don’t even care about that anyway.’”

But the voter education through her canvassing training made her feel that maybe her vote would do something. Maybe her opinion mattered. Maybe her voice could be heard.

Pluta found the line to vote snaking around the building when she got to the Douglas County Election Commission. The more she waited, the more excited she got, feeling inspired by those around her who were sacrificing their time to “do their part,” she said.

She recalled overhearing an elderly couple speaking. The woman was in pain and didn’t know if she could stand for much longer. Her husband reassured her that they could leave if she needed to. That felt unfair to Pluta, so she stepped out of the line and approached a poll worker to let her know about the couple’s concerns. The poll worker followed Pluta to where the elderly couple stood and then guided the husband and wife inside the building, where they were able to sit down while they waited to vote.

An hour or so later, the same couple approached Pluta, who was still in line. They handed her a bouquet of roses.

“The woman told me, ‘Thank you for allowing me to vote today,’” Pluta said. “That just made my day.”

After more than four hours in line, Pluta cast her own vote for the first time. She declined to share with The 19th which presidential candidate she supported, but listed her desire to expand abortion access as one of her top issues.

Nebraska is one of 10 states with ballot measures in 2024 that may enshrine abortion rights in their state constitutions. Pluta said she is the mother of three adult children, but does not think the government has the right to tell people what to do with their bodies. So, she voted “yes” on Initiative 439, which proposes to amend the state constitution to establish a right to abortion until fetal viability.

When Pluta finished she felt “like a different person.” For years, she and other formerly incarcerated women have felt like lesser citizens; they have often struggled to find housing, to find employment and to live without judgment by society. But Pluta said having the opportunity to vote made her feel like she was part of something bigger.

Around 3:30 p.m. Pluta walked out of the polling place, roses in her arm, and rushed like a kid to put her “I voted” sticker on her jacket.

“I guess I could have never anticipated how excited I would be, or how fulfilling it was for me to be able to vote and to be able to peel that sticker off and put it on the outside of my jacket,” she said. “It’s almost like a little badge or something, like you’re a Girl Scout. You want to make sure everybody knows you voted today.”