Member support made it possible for us to write this series. Donate to our nonprofit newsroom today to support independent journalism that represents you.

TUCSON, Arizona — Adriana Grijalva was getting ready to head to class at the University of Arizona in the fall of 2022 when she got a text message from her cousin telling her to stay put. The cousin, who works in maintenance at the university, had watched law enforcement descend on campus and reached out to make sure she was safe. A former student had just shot a professor 11 times, killing him.

Grijalva, who was just a few weeks into her first year of college, immediately thought of her sister, who also attended the university. Her stepdad, a music teacher, and her little brother were at a school not far from campus. Her mom must have been out running errands, she thought at the time. Text messages started to fly among members of this close-knit Latinx family as Grijalva tried to make sure everyone was safe and make sense of what was going on.

The deadly shooting left a profound mark on Grijalva personally and politically, moving her from passivity to advocacy. The threat of gun violence and the policies that could help stanch what she sees as a safety crisis in the United States are now her top issue heading into the 2024 election.

Four years ago, Grijalva wasn’t old enough to vote and her views on politics were loosely formed. This November, she’ll be among the estimated 4 million Latinx Americans who can vote for the first time. They’ll account for half of the growth in new eligible voters since the 2020 election.

Nationwide, Latinos make up about 15 percent of all eligible voters. But in Arizona — which helped deliver President Joe Biden’s victory in 2020 after former President Donald Trump won the state in 2016 — Latinx voters like Grijalva make up a quarter of all eligible voters, the highest share of any battleground state.

Latinas account for more than half of those voters. Nationwide, surveys show Latinas having exceedingly high rates of support for gun control policies. This is even more true in Arizona, where about two-thirds of Latinx voters back tougher gun regulations, a position that’s driven by the overwhelming support for these measures among Latinas in the state, across the ideological spectrum.

Grijalva’s generation came of age in the era of mass shootings in schools, their political views shaped by debates about how to prevent such tragedies from occurring again. She plans to vote for Democrats up and down the ballot because she sees the party as the key to gun-control policies, including universal background checks, a ban on assault weapons and red flag laws that could help prevent incidents of violence like the one on campus — and others that have hit close to home.

In 2011, a gunman opened fire on a constituent meeting in a grocery store parking lot in Casas Adobes, on the edge of Tucson, critically injuring then-U.S. Rep. Gabby Giffords and killing six people.

Latinx Americans have been the victims of two of the deadliest mass shootings in the Southwest. In Texas, a shooting at an El Paso Walmart in 2019 left 23 people dead and became known as the deadliest attack targeting Latinx people in modern American history. And in 2022, in the majority-Latinx city of Uvalde, Texas, 19 elementary school students and two teachers were killed in the country’s third deadliest school shooting to date. It took law enforcement more than an hour to enter the classroom where most of the victims were located and kill the shooter.

“When Gabby was shot here, I was 7 years old. Now I’m 20,” Grijalva said in an interview on campus. “When Uvalde happened, that really struck a chord — them waiting so long, this Latino community, a small town.”

Vice President Kamala Harris has emphasized gun violence prevention as one of her top issues and on the campaign trail, she has regularly talked about her support for reinstating the federal assault weapons ban and requiring universal background checks. Harris has also said in multiple interviews that she is a gun owner. During a Phoenix rally in August, Harris told the crowd that the United States was experiencing “a full-on assault against hard-fought, hard-won freedoms and rights.” These include, she said, “the freedom to be safe from gun violence.”

Trump’s campaign, which made inroads with Latinx voters in 2020, has put its focus on crime and law enforcement, leaning heavily on immigration as the source of America’s public safety issues, often with false and xenophobic claims about undocumented immigrants. In a speech to the National Rifle Association in February, Trump told the crowd that “no one will lay a finger on your firearms” if he wins the presidential election, and that he would terminate Biden administration regulations on gun owners and manufacturers.

The morning after the 2022 shooting, the University of Arizona campus reopened quickly, but Grijalva struggled to feel comfortable there. She had already been rattled by the mass shooting in Uvalde less than five months earlier. Now her sense of safety had vanished.

She was frustrated by how long it took school officials to update students in the shooting’s immediate aftermath. She thought in-person classes resumed too quickly.

She had been thinking a lot about gun violence prevention since the Uvalde shooting. “That one definitely hit close, but I was at first scared to get involved,” Grijalva said. The semester that followed the shooting on campus was quiet, but once she regained a sense of normalcy, “it was time to do something.”

She sought out the campus chapter of Students Demand Action, a student-led gun violence prevention advocacy group with just a handful of members at the time, and started recruiting for it and passing out flyers. She applied for a fellowship with Giffords, another advocacy group created after its namesake’s shooting and even though she was rejected, she dug more into the issue, “got educated, got more involved.” She then re-applied and got accepted, joining a cohort of other students who wanted to learn more about gun violence prevention efforts.

Now, Grijalva is working with Arizonans for Gun Safety, which is advocating for stronger background check laws, more rigorous requirements for someone to obtain a concealed carry permit and laws that punish gun owners when a child gains access to an unsecured weapon. Grijalva said she supports guardrails that will allow people to own guns but also stem violence.

“If I was in a politician role, I’d make that very clear: it's not about taking guns. It's just that it's not OK to access them so fast or easy,” she said. “If it's harder to get a driver's license, if it's harder to get an education than to get a gun … that's just not OK.”

Building enthusiasm among young voters has always been a challenge for political campaigns. With Latinx voters, the task carries more urgency. Latinx voters skew younger than the overall population and are susceptible to persuasion and low turnout.

Grijalva had felt discouraged by the debate between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump — then surprised when Harris replaced Biden on the Democratic ticket. There was no immediate gush about Harris, but there was hope about the stakes of the election. The Biden administration’s championing of gun violence prevention measures that had so energized her included Harris, too. She was particularly impressed that the administration had established the first-ever White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention — and under a Harris presidency, that work would continue.

Grijalva watched the Democratic National Convention from Tucson and was touched by its segment on gun violence, which included remarks from Giffords. The former lawmaker, who lives with the effects of a severe brain injury that affected her speech, told the audience about her journey learning to walk and speak again.

“The freedom from gun violence,” Grijalva said of the segment’s theme. “Wow.”

The campus shooting rippled through Grijalva’s family. Grijalva’s mom and her sister say the incident sharpened their views on gun violence, reshaped some family dynamics and will ultimately play a role in how they vote this election.

The three women live under the same roof in a heavily Latinx Tucson neighborhood, the kind of multigenerational living that sets Latinx families apart and one reason why experts say politically engaged Latinas wield a lot of influence over their communities. The ways Grijalva’s experience has impacted her family illustrate that dynamic.

Christina Valenzuela describes herself as a very cautious mom. She never allowed Grijalva or her other kids to crawl up on the counters, worried they might fall. The 44-year-old says the day of the shooting on the campus of the university both of her daughters attended remains a blur.

“It's scary as a mom because you do have to send your kids out, and you don't want to,” said Valenzuela, who in addition to Grijalva and her oldest daughter, Alyssa Grijalva, has two school-aged sons, a seventh grader and her “little guy,” a first-grader.

Valenzuela lived in Tucson when Giffords was shot and recalled two things about that time. One was being “terrified” that “trying to be just a supporter” at a political event could cost you your life. The other, a searing memory, is that a little girl, 9-year-old Christina-Taylor Green, was among those killed that day.

“I just think it’s awful the way things have gone with gun violence,” Valenzuela said. She lamented young people with mental health challenges gaining access to guns “so easily” and guns that “shoot so many people in so little time.”

Valenzuela didn’t grow up with guns in her home, but she remembers the collection of rifles that hung on the wall at her grandparents’ house. Her grandfather used to hunt near his ranch outside El Paso, but she never took part before he died when she was 8.

Alyssa described the shooting at the University of Arizona as traumatizing. She was working as a campus mentor for first-year students and had to help them one month into their college experience navigate a deadly incident on campus. “I understand if you don’t want to go to campus,” Alyssa would tell them, “If you guys don’t feel safe.”

She felt unsafe too.

Alyssa now works as a teacher at a bilingual school two blocks from the University of Arizona. A few weeks ago, when the school year started, she guided her students through drills for several emergency scenarios, including an armed intruder.

“I already told my kids, this is where you’d go, in the corner. The window in the door is blocked off,” she said. “It’s always on your mind as an educator. And I was honest with them. … I mentioned my experience at the U of A.”

The incident wasn’t immediately political for Grijalva’s sister or mom. Valenzuela didn’t cast a ballot in a presidential election until she was in her 30s and hasn’t ever been a regular voter. For a long time, she just felt like her “vote didn’t count” and these days, she sees politics as “ugly and vicious.”

Alyssa turned 18 just before the last presidential election and like her mom, voted for Biden.

Latinas like them are less likely to be registered to vote and less likely to turn out than women of any other racial group. In the last presidential election, just 56 percent of eligible Latinas cast a ballot, compared to 61 percent of Asian American women, 66 percent of Black women and 72 percent of White women, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

This cycle, both women plan to vote. They joke that Grijalva will make sure of it.

The campus shooting, Alyssa said, “was a big shift for everyone, but especially Adriana.” In her freshman year, her younger sister was a “shy little thing” figuring out where she was headed. Valenzuela said her youngest daughter had always been more reserved, except if she was performing in the mariachi band led by her husband, where Adriana played the violin.

“She wasn't always like this, where she's so vocal. It’s amazed me in the last, gosh, two years,” Valenzuela said. “She has taken such a front role in our family.”

Alyssa said she’s proud that her younger sister’s gun safety advocacy was born out of “her own experiences in our community.” “Latinos as a whole,” she said, don't always take up space with their voices. “There's still a struggle.”

Both Grijalva’s mom and sister are planning to support Harris. Her sister said she was “iffy” on Biden when she learned he was running again, but feels really inspired by Harris’ momentum. Valenzuela said she is “scared” about the fate of the country and wants to vote for someone with a “moral compass.”

When it comes to down-ballot races, or even Harris’ pick of Gov. Tim Walz for vice president, Alyssa Grijalva said she often turns to her younger sister for insight. “I’ll be like, OK, give me the backstory.”

In a matter of days, their mail-in ballots will arrive.

“We’ll sit at the table and do it all together, make sure that we turn them into the mailbox and they get shipped out — that's how we decided to vote as a family,” Alyssa Grijalva said. “That's more efficient for us, just making sure we get it done.”

Grijalva had been invited to speak about gun violence prevention at a July 14 event near Tucson that included Gabby Giffords. A day earlier, in Butler, Pennsylvania, a gunman fired at Trump during an open-air campaign rally, injuring his ear and killing two attendees.

In the wake of that tragedy, organizers in Tucson decided to cancel their event. “It was very upsetting because it was canceled because of gun violence, you know, so that really sucked,” Grijalva said.

Grijalva had spent hours working on her remarks for the event, which was organized to help energize voters worried about gun violence to support candidates who back gun control measures in November, including a congressional candidate in a nearby district.

“The election is fast approaching,” she wrote. “It’s a big year to choose the candidate best fit to fight with courage for the change we need to see on a local, state, and national level.”

In the months that followed, incident after incident reinforced that gun violence is a constant in her life and that of many Americans. On September 5, a shooting at a high school in Georgia left two students and two teachers dead. Grijalva described it as “heartbreaking.”

“Honestly… why do we keep letting this happen,” she said in a text message. “When is enough gonna be enough. Kids can’t learn if all they are thinking about is, are they gonna get killed.”

Then, just one day later, a 12-year-old student brought a handgun to Los Niños Elementary in Tucson and local law enforcement was immediately summoned.

The school is an 11-minute drive from Grijalva’s house, she pointed out, and “my nana lives four minutes away.”

In late September, almost exactly two years after the fatal shooting of the university professor, the University of Arizona campus was once again hit by gun violence: a 19-year-old from a nearby community college was found shot to death on a campus volleyball court.

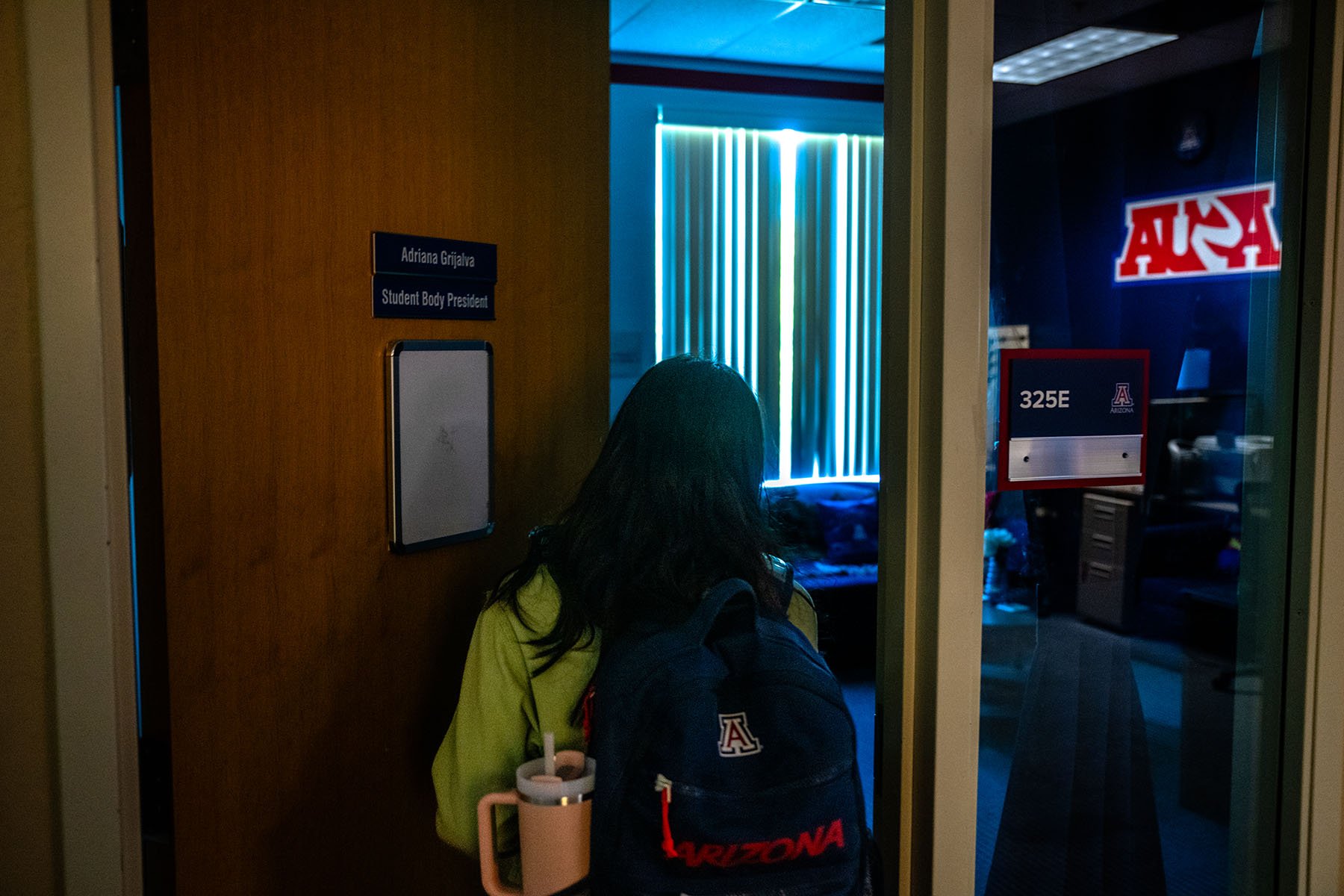

Grijalva is the incoming student government president, a role she says is not political in the partisan sense but that has given her a closer view into how school leaders respond to safety threats and how students grapple with incidents on campus. After the recent shooting, she has been busy advocating on behalf of students for more timely safety alerts and extra support, like a day off from class after a tragedy on campus.

“I’ve had a really hard time this week,” Grijalva said. “On a national level, it’s just happening everywhere … And it just sometimes feels like you can't do anything about it — like it's just so normalized.

“I did not think that the first statement I would write as president would be on gun violence.”