Your trusted source for contextualizing caregiving and Election 2024 news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Politics have never worked for Maria Amado. For years she has fought for better benefits for in-home child care providers in Connecticut like herself, devoting hours of her time — on days when there were few to give — to establish a nonprofit for caregivers. She’s talked to politicians who’ve visited her day care, telling them again and again how much caregivers need access to health insurance, a retirement plan. She took those concerns all the way to Capitol Hill.

It all amounted to nothing. So, why then, would she vote?

Politicians make promises, but “when they get to power they don’t do anything for us,” Amado said in Spanish. “We feel relegated. We pay our taxes, we do everything, and we see there is no benefit for us and for our families.”

Amado, who immigrated to the United States more than 15 years ago from Peru, has worked with kids ages 0 to 3 for the past eight years at Green World Family Child Care, the day care she runs from her home in Hartford. In that time, she also partnered with All Our Kin, a nonprofit that supports family child care educators, and last year she was the National Association for Family Child Care’s accredited provider of the year.

Amado works 11-hour days and has been struggling to remain fully booked and fully staffed — she can take up to nine kids, but currently has six. It’s hard enough to find someone to cover her to go to a medical appointment, and if she can’t, even harder to tell a parent she needs to cut a day short.

So on Election Day, instead of rearranging things to go vote, she’ll be interviewing two families for open day care slots she needs to fill.

“We are a large sector that doesn’t participate,” Amado said. “We don’t feel represented. There is a door there, but [politicians] don’t enter.”

About 94 percent of child care workers are women, and most are women of color. An estimated 2.5 million Americans are in the “sandwich generation,” caring for children and aging adults, responsibilities that for some are a major part of their lives. Again, most are women. But caregivers across the board are among some of the most disconnected voters nationwide, consistently participating in lower numbers than other groups.

A study of 12,000 non-voters in 2020 found that more than 60 percent of the most disconnected non-voters — people who are uninterested and disengaged from politics — are women, and especially single women with children. The newest 19th News/SurveyMonkey poll also found that while 10 percent of women and nonbinary people report not planning to vote in 2024 (compared with 8 percent of men), the figure climbs to 13 percent for women who are caregivers or people with children ages 3 to 11.

Caregivers often feel forgotten in the national discourse, both by politicians and by a system that fails to see how the barriers to voting — long lines, incompatible hours and a massive demand on their time to make sense of it all — are even higher for the people who already feel as if there aren’t enough hours in the day.

But this election cycle could be different. Child care has entered the 2024 discourse. Questions on child care and paid leave have been asked at both a presidential and vice presidential debate this year. And both presidential candidates have discussed the issue possibly more than ever on the campaign trail.

Vice President Kamala Harris has proposed capping how much families spend on child care at 7 percent of their income, as well as passing a larger child tax credit and an additional $6,000 child tax credit for families with newborns. Her running mate, Tim Walz, signed several notable care-focused policies as governor of Minnesota, including the country’s largest child tax credit.

Former President Donald Trump has not yet offered any child care proposals, giving a jumbled answer when asked about the issue, but he has expressed an interest in expanding the child tax credit. His running mate JD Vance, who is the father of three young kids, has been more vocal, expressing his view that the cost of day care could be lowered by incentivizing grandparents or other family members to help care for kids. The Ohio senator has also suggested lowering some education requirements for child care teachers. Vance has floated increasing the $2,000 child tax credit to $5,000.

The specifics are still sparse, and when child care came up in the first presidential debate between Trump and President Joe Biden, it was largely ignored as the two sparred over their golf swings instead.

But it has been enough to spark the question of whether this is the election cycle where caregivers are finally appealed to. It was 15,000 moms, after all, who petitioned to ensure child care would be a part of the debates — work spearheaded by Moms First, an organization that pushes for child care and other family policies.

“You see a growing swell of public opinion around asking candidates where they stand on child care,” said Jessica Sager, the CEO and co-founder of All Our Kin. That public pressure is sending a message: “It’s important for candidates to talk about these issues.”

Since the last presidential cycle, a pandemic has ripped through the child care sector, shuttering thousands of day cares and pushing parents — especially moms — out of the workforce. The current average cost of care would swallow 10 percent of a married couple’s annual income and 32 percent of a single parent’s. Paid leave, too, has become an issue that has gained attention in that time, both in how it exacerbates child care challenges and in how singular the United States remains as one of only seven nations on the globe without a federal policy.

“The only time campaigns talk about hot-button issues are when they become emergencies,” said Anthony Williams, the special projects director with public opinion research firm Bendixen & Amandi International who led the Knight Foundation-funded non-voters research project. “It’s not a coincidence that Social Security is a sacred cow that cannot be touched and issues related to young people with children — child care, early childhood education et cetera — don’t get the same level of support or funding or even attention.”

For caregivers, the emergency is here. But will they vote on it? And what’s at risk if they don’t?

Get-out-the-vote efforts aimed at caregivers, like making the mechanics of voting easier for parents and talking directly to non-voter caregivers about issues affecting them, are still nascent.

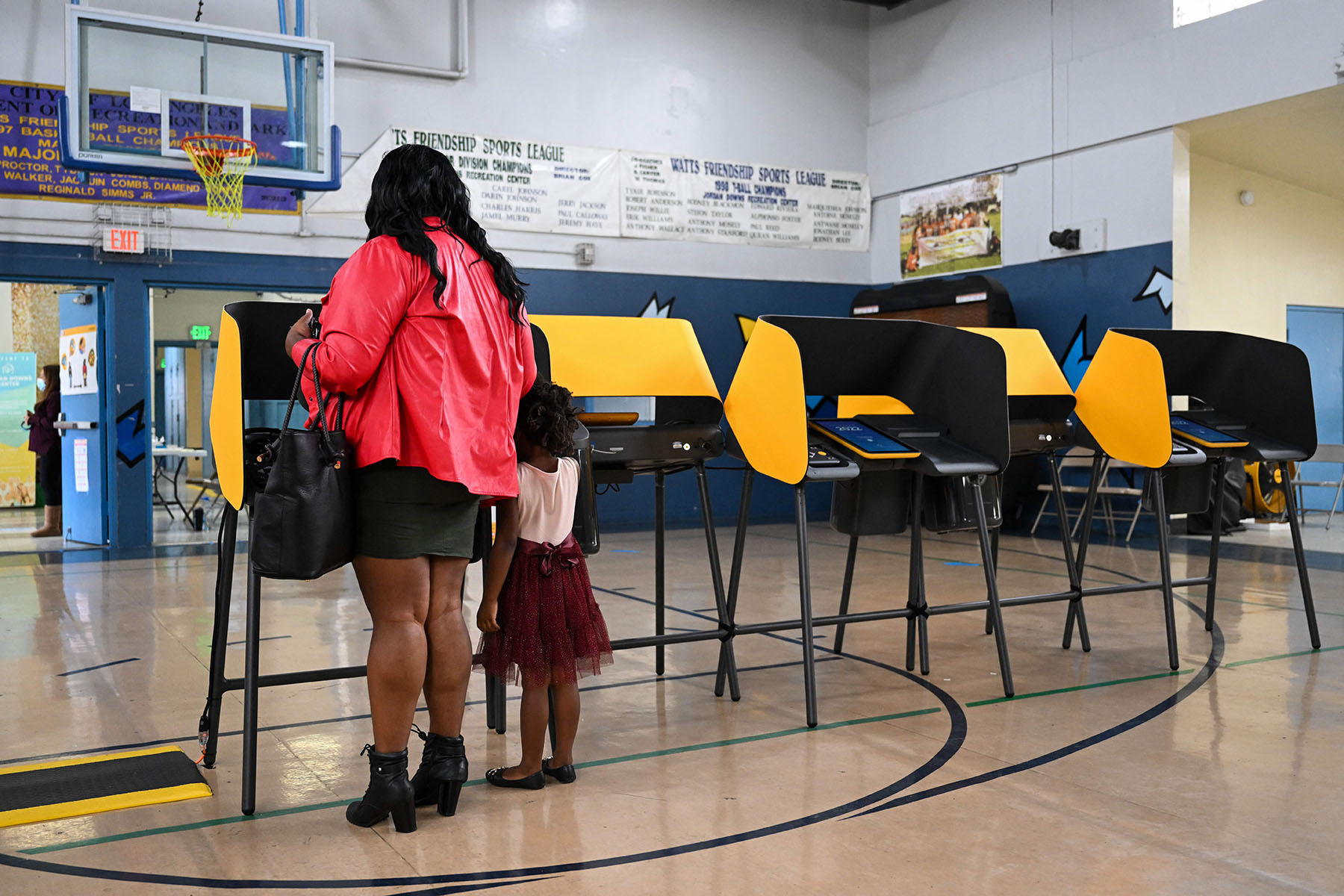

Chamber of Mothers, a nonpartisan group advocating for moms with chapters in 33 states, developed a voter education website this year that allows moms to pre-fill their ballot ahead of time after hearing consistently from parents that they have no time to focus on the election or are feeling apathetic about the process. How can they be expected to stand in line with a toddler, sometimes for hours? And when is the time to parse through confusing ballot language?

“What is consistent among these moms is they are exhausted, they feel dismissed by the political process, they are overwhelmed. Moms feel frozen about how to engage,” said Erin Erenberg, the organization’s co-founder and executive director.

It’s those kinds of things Nancy Glynn hears pretty consistently on the ground in New Hampshire as the state’s campaign director for MomsRising, a network of more than a million moms nationwide advocating for family policies.

“Let’s take a single parent who is probably working multiple jobs and probably only has an hour or two window to be able to make it to the polls at a certain time. Now we have a single mom who doesn’t speak English very well. A lot don’t know where the polls are. And then when you add in the transportation piece — that’s a whole other level,” Glynn said.

Even simple things, like polls that close too early, can be the decider between whether a caregiver votes at all. Some polling locations in New Hampshire close by 7 p.m., Glynn said. “How do you get there in time and how do you feed your kid?”

“All of those barriers building on top of each other just tells them their vote doesn’t matter anyway,” Glynn said. And that’s where a lot of non-voter caregivers ultimately stand: “If my vote was so important, why is it so difficult for me to do it?”

Professional caregivers, who have been targeted by get out the vote efforts even less than mothers, also consistently cite not having time to engage. On the ground in Arizona, Care in Action, a nonprofit that advocates for domestic workers, has been knocking on doors reaching domestic workers who are often shocked that anyone is talking to them at all, said Anakarina Rodriguez, the state’s civic engagement program manager for Care in Action. The group is largely advocating for workers to support Harris.

Many of the domestic workers Care in Action tries to reach are Latina immigrants, but Rodriguez said the group finds that often husbands or partners will be the ones to respond in their stead when canvassers come knocking. Machismo, a traditional Latinx belief that props up toxic masculinity, makes even speaking out on politics difficult for those workers, Rodriguez said. That’s a barrier in itself.

Trying different hours, like reaching them on Mondays because many work weekends, has helped them talk to workers directly. What they hear when they do speak to them are questions about the voting process — registration, ballot measures, the judges. The group is one of few that speaks regularly to child care workers, more than a quarter of whom nationwide are Latina.

“Care and domestic work is almost 24 hours in a way. What you hear is people don’t have time, and I think that’s very real,” Rodriguez said. “I feel like voting is a little overwhelming in a sense of what they have to worry about in their day-to-day lives, especially since they are taking care of somebody who might need extra.”

Simplifying the logistics of voting could go a long way, advocates have found.

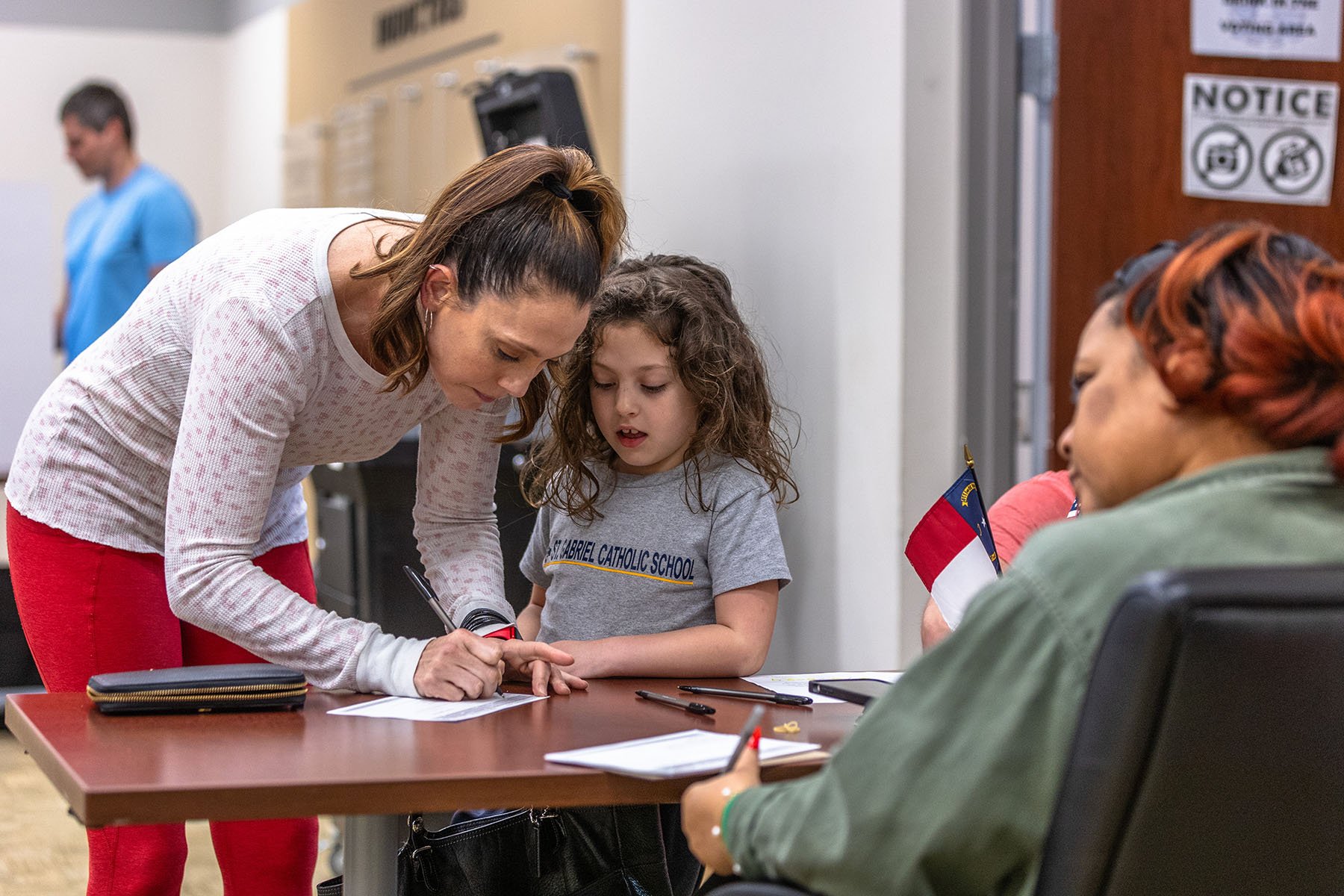

In North Carolina, a nonprofit called Politisit will pilot the first-ever child care for voters reimbursement program this year. Families need just fill out a simple Google Form detailing the kind of child care they’ll need to go to the polls and Politisit will reimburse them for the cost of that care for up to two hours.

It’s an expansion of a program the organization has been providing since 2020, when it partnered with local nonprofits like YMCAs, churches and child care centers within walking distance or a short drive from the polls in certain states to provide a free space for voters to drop off their kids while they cast their ballots. More than 115 families have been served.

This year, free child care drop-off sites will be available in at least nine states, but executive director Emily Teixeira said Politisit wanted to go further after some families told them they would rather just set up their own child care, like a babysitter, instead of dropping their kids off at a site.

The pilot program in North Carolina this year will allow them to test both physical sites and reimbursements so they can scale the program for future elections, Teixeira said, especially if care continues to command space in the national presidential election discourse.

“Stress, anxiety on parents is at an all-time high, and I think we continuously pile these things onto people’s plates. We’ve set these standards so high of what participation should look like,” Teixeira said. “It’s just showing up.”

Since 2016, MomsRising has also been trying to make showing up to the polls easier, creating treasure boxes at poll sites with activities and small toys for kids to keep them occupied while their parents voted. Beth Messersmith, the senior campaign director for MomsRising’s North Carolina chapter, said the boxes have been so popular some families pick polling places based on which ones have them. This year, interest has exploded: Her team put out an appeal for volunteers to help staff the treasure boxes during early voting — all the slots were full within five days.

Messersmith talks directly to caregivers who tell her they aren’t interested in the election, and she gets it. When her son was born 19 years ago as a micro preemie, nine weeks before his due date, it was the first time she faced the difficulty of voting as a parent. She had to devise a detailed plan that allowed them to vote while limiting human interaction, fearing they would bring an illness back to their tiny baby. Then she watched how hard it was for her mother, another lifelong voter, when she was undergoing cancer treatment. They had to ensure she had signed up in time to receive a mail-in ballot to vote from home.

Two decades ago, no one was talking about the issues affecting parents. Messersmith remembers sitting in an empty neonatal intensive care unit until 6 p.m., when the doors would burst open and parents who had no access to parental leave streamed in to see their newborns. And while access to paid leave has increased, the strains on parents are still enormous. In August, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy issued a national advisory called the stress of parenting “an urgent public health issue.” Given that reality, expecting parents to carve out the time to vote can be unrealistic, Messersmith said.

“I get that when people are really strained, things fall off the radar screen. I don’t judge people for that,” she said. “A whole lot of it is hearing with respect that these are not excuses people aren’t voting. They’re reasons.”

Now, as she watches issues like child care and paid leave in the national conversation, she feels hopeful again.

“It does feel kind of like watching a snowball,” she said. It’s been slowly rolling down that hill, gradually growing bigger. Now she has a pitch whenever she talks to voters who can’t see just yet that it started out as just a speck.

“I hear you. It is hard when you feel like your voice doesn’t matter,” she tells them. “But I guarantee you when you show up and say, ‘This is important, and this is the kind of thing you can win and lose elections on,’ it will matter next time. The fact that they are talking about this now is the result of decades of work.”

For those who still feel like they’ll sit out the election, the question is what message could reach them, if anything at all?

Williams, the researcher, said that non-voters will participate if they feel that a candidate “is looking at it from your perspective and actually cares about you.”

“It’s a feeling — they vote on who they think has their interests at heart. Who do they trust in the position?” he said.

Advocates said they want to hear candidates give far more specific policy proposals. While there may be differences of opinion on funding child care, candidates could say they want to prioritize finding a solution, Erenberg said. And those solutions should specifically name the needs of in-home child care providers, Sager said.

That would cut through for her, said Amado, the in-home provider in Connecticut who is sitting out the election. “For them to say, ‘We want to propose this and we are going to do it but we want to do it in partnership with you all.’ We are excluded from everything.”

If they could be reached, then those voters could have a hand in shaping the policies that affect them, Erenberg said. But it needs to be a partnership.

“When you’re depending on the most overwhelmed, the most exhausted group of folks to fix the system for themselves, that is incredibly hard to sustain,” Erenberg said. “Very often we rely on the people who are harmed to undo and fix the harm. I’m grateful to be in a moment where moms are banding together and insisting that our concerns become a priority. I just think that we’re sort of at the beginning of that wave.”

With one month left until the election, the beginning of that wave looks like this: Around dining tables across the country right now, moms are writing postcards. Thousands of them.

This year, MomsRising is expected to have the most volunteers ever in its history to help get out the vote. Kristin Rowe-Finkbeiner, the organization’s co-founder and executive director, said they are projecting some 80,000 to 90,000 mom volunteers come Nov. 5, many of them engaged in sending other moms texts with information on voting, and on filling out the postcards.

The cards feature an illustration of mothers in a field with their children and the words, “We love our kids more than anything. Vote for our freedoms, our families, our futures.”

On the other side are handwritten notes, all going out to moms who are infrequent voters, or who have never voted at all.

Life is hectic, they read. Make time to vote!

Voting is your superpower.

Be a voter. Raise a voter.

To check your voter registration status or to get more information about registering to vote, text 19thnews to 26797.