Your trusted source for contextualizing race and Election 2024 news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Call it a mother’s intuition. After former President Donald Trump repeated a vicious smear about Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, during his September 10 debate with Vice President Kamala Harris, many parents in that community instinctively kept their children home from school. They were right to be concerned. In the days following Trump remarking on national television that these immigrants are eating household pets — a debunked rumor that first spread on social media — the threats rolled in.

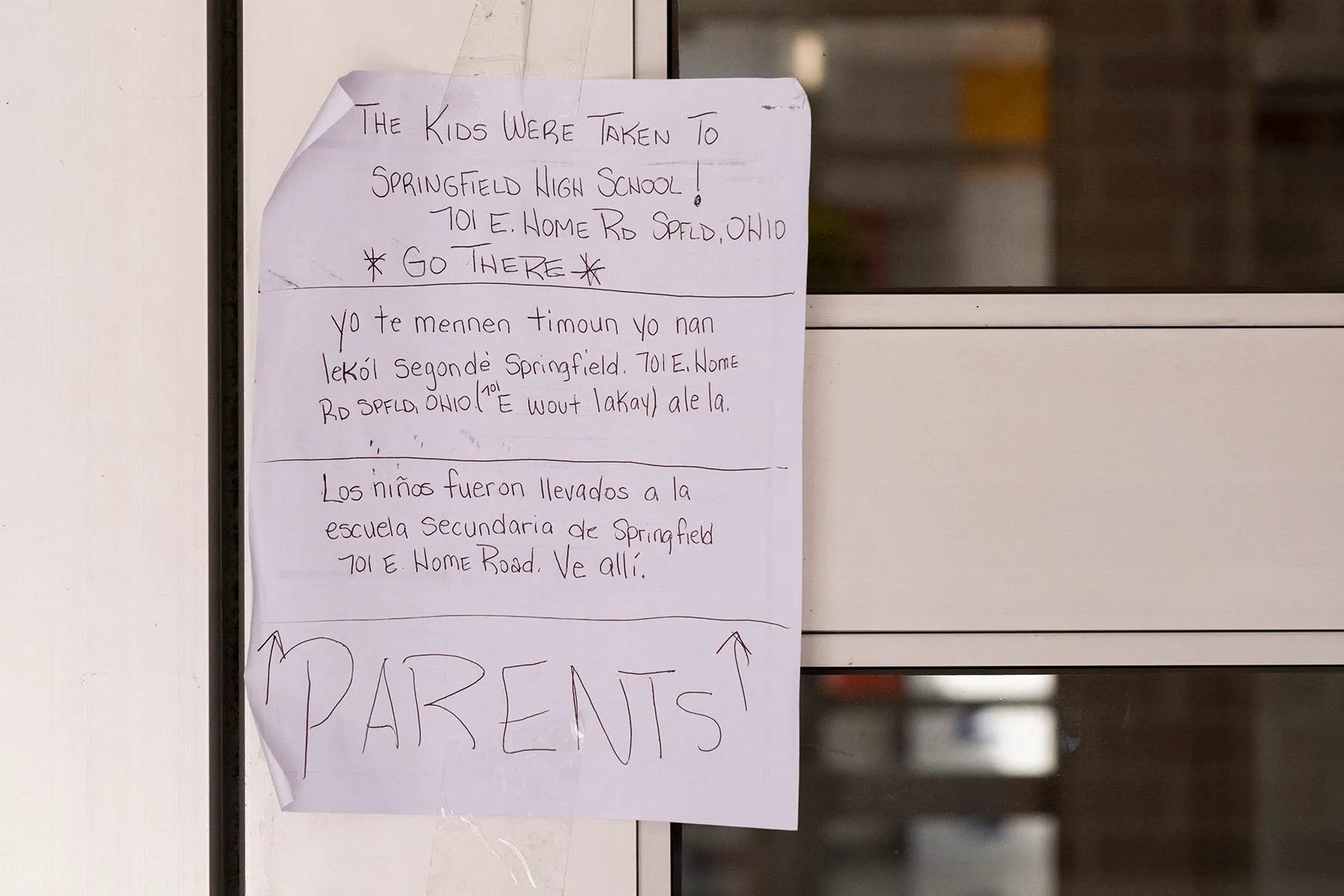

The bomb and mass shooting threats that started shortly after the debate and continued through the weekend forced evacuations and closures of government buildings, hospitals, a university and schools in Springfield. Although Trump’s words have imperiled Haitian immigrants, he has not withdrawn his claim; he has doubled down on it. On Thursday, while campaigning, he suggested Haitians had ruined “beautiful Springfield” and were not in the city legally, although Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said they are living and working there lawfully. Trump also insinuated the immigrants are involved in sexual violence against “young American girls,” continuing his pattern of linking immigration to the predation of White women and girls.

The targeting of Haitians in the smalltown Midwest has led to an outcry of support from the public, policymakers and immigration advocates. The National Parents Union, a woman-led organization made up of parent advocacy groups fighting for equity in education, criticized “the reckless and irresponsible comments” from Republican leaders and announced that it “stand[s] with the families of Springfield” in a statement on Friday.

But no one empathizes with Springfield’s Haitian community like Haitian Americans themselves, they say. The 19th spoke with scholars and immigrant advocates, mostly women of Haitian heritage, about the repercussions of Trump’s words. They contend that his claim — and the hate before and after it — are nothing new: Due to the unique ways race, religion and resistance have intersected in Haiti’s history, immigrants from the Caribbean nation have experienced a specific brand of xenophobia in the United States, even as Black immigrants in this country lack visibility.

“This kind of narrative has been going on since at least the middle of the 19th century,” said Danielle N. Boaz, professor of Africana Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. “We can connect all of this back to the thing that Haitians did that was unforgivable to people of European heritage, which is they had this . . . rebellion that started in the 1790s and culminated in what historians have sometimes called the only successful slave rebellion in history, where they were able to defeat not only the French but other foreign powers.”

The 1804 creation of Saint-Domingue, later Haiti, left slaveholding societies terrified that the human beings they held in bondage would also rebel. For securing their freedom, Haitians were demonized, with the Vodou religion often used to make wild claims against them, Boaz said.

“So, over the years, the narrative just kind of increases about how Haiti is this barbaric place,” she said. “It’s run only by Black people.”

Trump reinforced the barbarism messaging by implying Thursday that Haitians are “savage criminal aliens.”

Despite Springfield Police denying any “credible reports or specific claims” of Haitians abusing animals or committing other crimes, Trump’s allegations have reverberated nationally. Christopher Rufo, who has led the national push against critical race theory in schools and is a trustee for the New College of Florida, where hundreds of books on gender and diversity were discarded last month, offered a $5,000 “bounty” to anyone with evidence of Haitian immigrants in Springfield eating cats. In Florida and New York — the states with the largest Haitian-American communities — Haitian-American leaders condemned Trump’s remarks and similar statements by his running mate, Sen. JD Vance of Ohio.

The bomb and shooting threats targeting Haitians disproportionately place pressure on mothers, said Taisha Saintil, senior policy analyst for the UndocuBlack Network, which advocates for Black immigrants. Often children’s primary caregivers, women rearrange work schedules, stay home or make childcare plans when schools close, losing household income in the process.

“Women are often the ones managing the day-to-day fears, picking up and dropping off children, and trying to shield them from the psychological trauma of these threats,” Saintil said. “This gender dynamic adds another layer to the stress, as women feel pressure to keep things normal for their families while silently shouldering the weight of their own fear and frustration.”

Having immigrated to Florida from Haiti in 2006 at age 9, Saintil said that she feels for Springfield’s Haitian community. Before moving to diverse Fort Lauderdale, Florida, she briefly lived in a White community where she said her classmates taunted, spat on her and called her a cat-eater.

“I remember . . . the fear, waking up every single day knowing that I’m going to get bullied, nobody wanting to talk to me, sitting at the lunch table by myself,” Saintil said. “When I compare it to what is happening now to the newly arrived kids, I think about just how . . . the bullying will mark them for the rest of their lives.”

Lured by manufacturing jobs, an estimated 15,000 Haitian immigrants have settled in Springfield — a mostly White town of just under 60,000 people — starting in about 2017. Before then, Springfield experienced an economic downturn caused, in part, by population decline. Then, the immigrants arrived, giving the city an economic boost.

Valerie Lacarte, a senior policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute’s U.S. Immigration Policy Program, said that immigrants typically settle in areas because they know they can find reliable employment or their ethnic community already lives there. Springfield wasn’t previously home to a Haitian community, but state officials reportedly advertised the city’s livability and jobs, news that attracted migrants.

“You have employers who are hiring these people, so from the job market perspective, that’s a good thing. You have a match,” Lacarte said.

But this mutually beneficial development did not prevent tensions, which, last year, worsened after a Haitian immigrant crashed into a school bus, killing one child, Aiden Clark, and hurting nearly 30 others. Still, Nathan Clark, Aiden’s father, spoke out at a city commission meeting last week to denounce immigration foes for exploiting his son’s death. Anti-immigrant residents, meanwhile, have complained that Springfield lacks the infrastructure for population growth.

“It’s tempting to think the growth of immigrants, that’s what’s causing the problems,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, coauthor of “Framing Immigrants: News Coverage, Public Opinion, and Policy” and a University of California, Berkeley, researcher. “It’s the politicization of immigrants, and especially in places that have significant Republican voting populations, the scapegoating of immigrants tends to be higher. This is an issue we’ve seen time and again in the American heartland, places that are depopulating, places that are short of workers, that actually benefit from immigrant workers, but you have people . . . tapping into these national dynamics, when it comes to race and xenophobia, to win elected office.”

Officials must “be intentional about social cohesion” to avoid conflict between the longtime residents and the Haitian transplants, said Lacarte, the daughter of Haitian immigrants. It’s important to make sure that both the U.S.-born and foreign-born community members get the attention and resources needed to grow together as a diverse community.

Longtime residents may misunderstand why people who look and sound different from them are moving in, Lacarte said. They witness the demographic shift, but they don’t realize these changes can be helpful. Then, bad actors deepen anxieties by spreading disinformation about immigrants.

“Immigrants have been not only filling these jobs and helping grow the economy. They have their own demand for goods and services,” Lacarte said. “They send their kids to school. They even, in some cases, create businesses . . . and that grows the economy.”

During the presidential debate, Trump did not portray foreign-born workers as a positive but as a threat to Americans, accusing immigrants of taking jobs from Black workers. This framing overlooks that immigrants fill jobs the native-born population doesn’t pursue, Lacarte said, and that more workers are needed as birth rates decline and the White population ages. It also belies the fact that Black immigrants exist.

About one in five Black people are immigrants or the children of Black immigrants, the Pew Research Center reported in 2022. Africans have driven Black immigrant growth; their population increased by 246 percent between 2000 and 2019. In 2005, The New York Times reported that more Africans were entering the United States than since the slave trade. Today, Africans make up 42 percent of the Black foreign-born population, while Caribbean immigrants make up 46 percent. Of the latter, most come from two countries: Jamaica and Haiti.

After footage of Border Patrol agents on horseback confronting Haitian migrants in Del Rio, Texas, went viral in 2021, Saintil said she received multiple messages disclosing, “I did not know there were Black immigrants. Where did they come from?” She assumed, due to her profession, that people knew the United States had Black immigrants.

“Most of my work now has been to raise visibility of Haitian and Black immigrants,” Saintil said. “We’re the most detained, the most placed in solitary confinement. Our bail bonds are higher. So, the same things that are happening to African Americans in the criminal justice system are happening to Black immigrants in the detention center. Our asylum claims are the most denied because immigration judges don’t trust our pain.”

Long before the debate, Trump disparaged Black immigrants. In 2017, he reportedly said that Nigerians lived in “huts” and Haitians “all have AIDS.” The following year, he labeled Haiti, African nations and El Salvador “shithole countries.” In Springfield, local Republicans have echoed Trump’s remarks. In addition to the pet-eating allegations, they’ve accused immigrants of being in gangs, spreading disease and practicing “voodoo” rituals, claims police have denied.

As Haiti became the yardstick for measuring whether Black people could participate in society equally, attacks on its character escalated. By the 1880s, stories spread about Haitians engaging in cannibalism and human sacrifice, especially of White children, Boaz said. Told repeatedly, these stories inform the rumors about Haitians in Springfield today, and they may jeopardize women.

“Historically, women in marginalized communities, whether immigrants, ethnic minorities, or refugees, have been specifically targeted for intimidation,” Saintil said. “This may be because some view them as ‘easier’ to attack or harass than men. . . . In this context, when Haitian women are being targeted for threats, harassment or even racial slurs in public spaces, the consequences are far-reaching. This not only creates an atmosphere of terror for women but can also ripple through the entire family.”

Haitian-American anthropologist Gina Athena Ulysse, a professor of humanities at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said that she’s tired of defending her personhood and identity. Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Ulysse wrote a book called “Why Haiti Needs New Narratives: A Post-Quake Chronicle” because she found the dehumanizing remarks about Haitians then disturbing.

“We’re always having to refute as opposed to having an identity that is an affirmed one,” Ulysse said. “There is a profound disappointment that in 2024 that I am listening to someone who is running to be the president of the highest nation in the land say something this surreal, this absurd. But I’m also someone as a Black woman, as a social scientist, as someone who understands race and racial construction, what that is meant to do, and that is to paint Haitians as the ultimate ‘others,’ cannibalists and otherwise, so that it can keep fueling this narrative that’s necessary to strip people of their humanity.”

Ulysse said that the broader immigrant community faces xenophobia, too. One study concluded that the level of anti-immigrant rhetoric in the Republican Party today rivals anti-Chinese sentiment during the late 1800s, a period that restricted Chinese immigration. Chinese immigrants have also been accused of consuming dogs and cats, insults revived during the onset of COVID-19, which Trump called the “China virus.”

“He’s gone from talking about Mexican immigrants as predominantly being criminals and rapists to then talking about immigrants as vectors of disease and now using similar kinds of dehumanizing language to talk about . . . not just what they eat, but the kind of the social threat they supposedly pose to American society,” Ramakrishnan said. “I think the kinds of emotions it’s supposed to evoke are emotions of disgust, of othering and reduced empathy, and also support for drastic measures like rounding up and deporting people who are not deemed to be American.”

If Harris becomes president, she would not only be the first woman in the Oval Office but also the first person of South Asian and Caribbean heritage. Might that change perceptions and policies related to Caribbean immigrants?

“No matter how well meaning one person may be, they’re part of a social structure and a system that makes decisions,” Ulysse said. “She’s not going to make decisions by herself, so what difference does it make that she’s from the Caribbean? She’s got advisors. She’s got to think about Congress. She’s got to think about the Senate. She’s got to think about geopolitics and history.”

When Trump took aim at Haitian immigrants during the debate, Harris laughed in apparent disbelief but did not rebuke him. Ulysse finds it disturbing that many people laughed at Trump’s claims because, as absurd as they are, they’re endangering Haitians.

On Friday, President Joe Biden called the attacks on Haitians “simply wrong,” noting that White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre is “a proud Haitian American.”

Along with being terrified and traumatized, Saintil said the Haitian children and parents impacted by the threats and smears likely feel betrayed.

“You’re getting it from a country that you thought you could be safe in,” she said. “You’re getting it in a country that you’ve been hoping to be in because you thought your life would be better, but now you’re being treated worse than dirt. You’re being called a savage . . . How do you go on from there?”