This article was copublished with Pittsburgh’s Public Source.

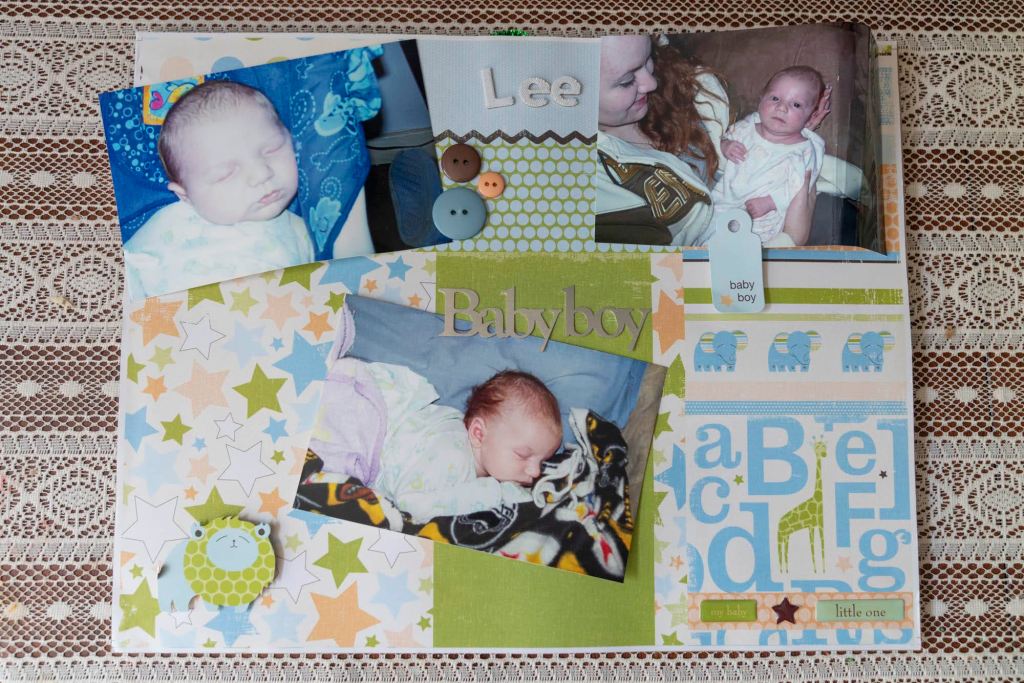

On a summer day, Lee sat waiting in a doctor’s office, playing GamePigeon on his phone, telling family stories with his mom and deciding where to get dinner.

It seemed like an ordinary afternoon, yet the reason for Lee’s appointment was far from ordinary.

Lee, 17, was there because the UPMC health system, headquartered in Pittsburgh, had cut off the gender-affirming care he’d been receiving for two years — a change driven by a federal executive order. A pharmacy mix-up meant his final puberty blocker shot never came, and the “weaning off” period his doctor had promised vanished. Within a month, he was experiencing hot flashes he hadn’t felt since starting treatment.Lee was devastated when he learned he could no longer receive treatment. “You feel like you’re starting from rock bottom,” said Lee, who plans to start classes at Carlow University this month.

The sudden disruption of care brought national policy directly into Lee’s home. On June 30, UPMC cut gender-affirming care for patients under 19 citing compliance with a January executive order from President Donald Trump. However, the care remains legal in Pennsylvania, and critics say the decision was less about the law than about protecting federal funding. A UPMC spokesperson said while they “empathize deeply” with impacted patients, the Trump administration has made it “abundantly clear” they can “no longer provide certain types of gender-affirming care without risk of criminal prosecution.”UPMC’s move mirrors a broader trend. Major health systems — from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles to Penn State Health — have also ended gender-affirming care for minors. The policy has prompted a lawsuit from 17 Democratic officials, including Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, who argue the Trump administration is pressuring providers to cut services even when they remain legal.

For two years, Lee had been treated at UPMC with puberty blockers and testosterone. Suddenly he and his mom Nicole — identified here by first names only because of concerns for privacy and safety — were scrambling for a new provider. Smaller practices seem to be “flooded” with former UPMC patients, Nicole said. “No one is taking on new clients.”

When they saw Lee’s doctor at UPMC in mid-July, the physician confirmed no more puberty blockers could be prescribed and refused to answer questions about finding care elsewhere. Nicole asked if it was safe to seek testosterone out of state. “They were just like, ‘I can’t tell you anything,’” Lee recalled.

Growing up, coming out, finding care

The uncertainty hangs over what should be an exciting time for Lee. He recently graduated high school a year early and, having grown up about 20 miles east of Pittsburgh, thinks it will be easier to connect with more queer people once he leaves Plum to study at Carlow University. “The suburbs are fine,” but “there’s more people that are open-minded in the city,” he said.

Lee worked to graduate a year early from high school, thinking it might allow him to more quickly pursue top surgery — a procedure that alters the chest to align with a patient’s gender identity. Only a few months ago, Lee was discussing the procedure with his UPMC doctor “and then this all got shut down” due to Trump’s executive order, he said.

Lee’s path to care wasn’t smooth. He came out as transgender at 13 and was nervous about how mom would react. To his surprise, Nicole was “overwhelmingly supportive” and has since been his “backbone for everything,” he said. But his childhood pediatrician was dismissive, telling a long story about a woman who once identified as a lesbian and later married a man — suggesting his gender dysphoria was just a phase. “Just hang in there and don’t do anything,” Nicole said, paraphrasing the doctor’s advice.

At 15, Lee started receiving gender-affirming care from UPMC. The effect was immediate: less anxiety, less depression. “I don’t know what I would’ve done if I had to wait longer,” Lee said. He described the treatment as a “life-changing process.”

These days, Nicole worries about more than finding a doctor. She fears parents could one day face prosecution for helping their children access gender-affirming care in any state. “I have two little ones I need to be here for,” she said, referring to Lee’s younger sisters.

The Trump administration has intensified its stance, with Attorney General Pam Bondi issuing subpoenas to more than 20 doctors and clinics — including UPMC — for records related to gender-affirming care for minors. Bondi has said providers who have “mutilated children” will be prosecuted under the False Claims Act.

Lee closely follows developments regarding transgender rights. “I know that there’s a specific target on my head,” he said.Medical experts widely agree that gender-affirming care improves mental health outcomes for transgender people. A 2018 Cornell University review found that 93% of 55 studies surveyed reported improved well-being after transitioning. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found youth receiving such care had a 60% drop in depression and a 73% drop in suicidality.

Even so, 27 states now ban or partially ban care for minors. Federal pressure adds another layer. Lee believes policymakers should focus on reducing stigma around being transgender, not restricting medical treatment. “Our society does not respect people like us,” he said. “They’re pushing us away and that’s why we’re getting depressed.”

A new doctor and an uncertain future

On July 26, Lee saw a glimmer of hope. Nicole secured an appointment with a private provider in Mt. Lebanon. The doctor assured them that continuing Lee’s treatment was legal and said she could provide it for him as a client. “UPMC made me feel like there were no other options,” Lee said. The new doctor “gave us the feeling that we can’t give up.”

Still, fears remain. “I’m always going to be on edge with this administration,” Lee said. “I think this is just the beginning of them trying to get rid of all gender-affirming care.”

Lee and Nicole have talked about leaving Pittsburgh — or even the country — if needed. Options include moving to Maryland or studying abroad for a semester. For now, Lee’s staying put.

“I don’t want to uproot my life and live somewhere else,” he said, but admitted “I have to somewhat consider it.”

Caleb Kaufman is a photojournalist for Pittsburgh’s Public Source. He can be reached at [email protected] or on Instagram at @caleb_kaufman_photography.

Recommended for you

From the Collection