This story was co-reported in partnership with Connecticut Public. Listen to the radio story using the audio player below.

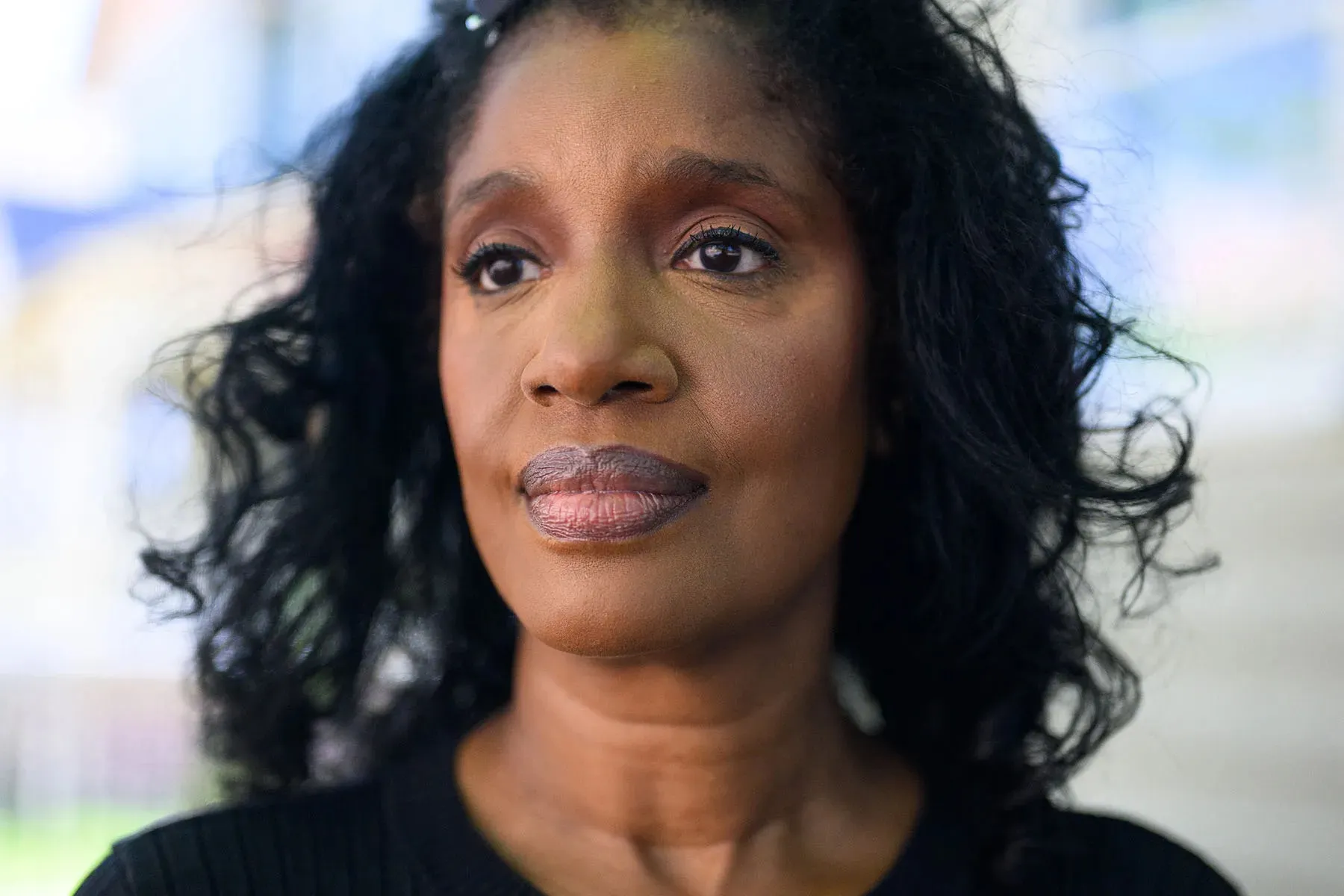

HARTFORD, CT — Everyone seems to know Diane Lewis on The Avenue — and those who don’t stare at her like they want to.

She is something of a local activist for the residents of Hartford’s Upper Albany neighborhood, a majority-Black area peppered with more than a dozen churches and seven Caribbean restaurants across a one-mile section of Albany Avenue, better known as just “The Avenue.”

The sight of Lewis walking down the street is hard to miss. On a chilly Thursday in April, she wears a knee-length, striped sweater dress enveloped by a red wine colored fur coat. She glides off the sidewalk and through busy intersection after busy intersection seemingly unfazed by the oncoming cars — or the photographer and two reporters struggling to keep up behind her.

“Y’all cross the way y’all cross,” she suggested with a laugh. “I can’t wait.”

Periodically, Lewis stops when she sees a familiar face. Each time she asks their thoughts about a law she advocated for that made phone calls and email free in Connecticut’s prisons and juvenile facilities two years ago this summer. The enthusiastic responses to her question reveal the depth of relief in this community, which has been hit hard by mass incarceration.

“Yoooooo!” said Hartford resident Ivelisse Correa, reflecting on the years before free prison calls. “OK, so my dad went to jail, right, and you don’t have no idea how much debt we racked up. You’ve got children, you’ve got parents, you’ve got siblings who, through no fault of their own, it’s either go into debt or cut off communication with this loved one.”

Correa’s father went to prison for three and a half years when she was a freshman in high school, and a number of her friends and neighbors faced similar circumstances. A report based on 2020 data found that Upper Albany had one of the highest incarceration rates in Hartford — 1,917 per 100,000 people, or more than four times the rate statewide.

At the same time, the neighborhood’s median household income is about $24,000, and more than 30 percent of families live in poverty. A $5 prison phone call chipped away at the little money people have for essentials like food, rent, medicine and clothes.

In the two years since the law Lewis championed went into effect, the free phone calls and emails from prisons have been “life changing,” Correa said. “I’ve spoken to my friends that I’ve been able to stay in communication with,” she said. “I really wish that I had this as a kid, but I’m grateful that there’s going to be other children who can stay in touch with their parents.”

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

As Correa speaks, Lewis nods in agreement. Her advocacy in prison phone justice began after her 17-year-old son went to prison in 2004. At the time, Lewis didn’t know anything about how the prison phone call system worked, but she knew she needed to talk to her son every day. Hearing from him became a bit of an obsession for her. It was the only way she knew he was safe.

Each 15-minute call cost her between $3 and $5. She usually called her son four times a day, which amounted to about $100 per week or $400 a month give or take. More than 20 percent of her $2,000 monthly paycheck went to calls with her son. Sometimes, Lewis was late on her bills and her utilities were cut off. She would often work all day and skip eating lunch to save money. The daily phone calls were first priority, she said.

During those years, Lewis also paid thousands of dollars in legal fees for her son’s case and cared for her sister’s three kids. She doesn’t remember exactly how she pulled it off. “You just do it,” she said. “It was a struggle because you have to do without stuff and as a mother, that’s what you do.”

That’s what mothers do.

Lewis repeated those words multiple times in interviews with The 19th and Connecticut Public, and it’s a conviction that other women throughout Upper Albany embody. In this community, it’s difficult to find someone who hasn’t been touched by incarceration, Lewis said. There’s a sisterhood of mothers with incarcerated children who look out for one another. If one of them needed a few dollars to make a call to their kid inside, the others would step up to make it happen.

In many ways women, particularly Black women, are the oxygen masks for a population that has been largely forgotten by society. An estimated 1 in 4 women around the country has a loved one in prison. They are often providing the financial and emotional support for these loved ones and many do it while also caring for children at home.

“The stories of people who would come forward sharing about the burden that these calls had created for them and their families were disproportionately Black women in Connecticut,” said Brian Highsmith, an academic fellow in Law and Political Economy at Harvard Law School who helped with Connecticut’s free prison calls campaign. “That story is different for every family, but what is shared across those stories is the gendered and racialized harms of this system.”

In 2019, Lewis connected with Bianca Tylek, a lawyer who founded the nonprofit organization Worth Rises, which had successfully campaigned for free jail calls in New York City and San Francisco. Tylek wanted Connecticut to be the first state to allow for free prison calls. Worth Rises built a coalition of local advocacy groups, researchers and family members like Lewis to push for the legislation.

To Lewis’s surprise, the measure passed in 2021 and went into effect the following year. She still remembers the excitement in Upper Albany as word spread about the new law. Messages of praise flooded her social media, email and cell phone.

“I didn’t experience any free phone calls because my son had come home a few months prior to the legislation, but the emails I got, the texts I got from Black women were amazing,” Lewis said.

For years, this community had felt ignored or disregarded by politicians and government institutions. “You know how it feels when nobody don’t pay you no attention? Then all of a sudden they think, ‘Oh, God, they must have really been thinking about us to have passed this bill,’” Lewis said.

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

With the Connecticut law, Worth Rises and the activists made history by taking on the multibillion-dollar privatized prison telecom industry, which runs costly prison communication networks in most states. Connecticut officials evaluated proposals from a number of vendors but ultimately decided to keep using its telecom provider Securus, one of two companies that together account for about 70 percent of the correctional telecommunications market in the United States.

This means that Securus remains responsible for the management and maintenance of telephone and messaging platforms and infrastructure inside the state’s prisons. The key difference with the new law, however, is that the burden of paying for the emails and calls has shifted from incarcerated people and their families to the state.

Connecticut’s law helped to ignite a wave. Soon after, California, Colorado, Minnesota and Massachusetts passed similar legislation. State legislators in Virginia, New York state, New Jersey and Hawaii have also considered bills this year.

To measure the impact of Connecticut’s law since its passage, The 19th and Connecticut Public interviewed two dozen people, including currently and formerly incarcerated people, family members, government officials and advocates. People in prison answered our questions using the same official email platform they use to talk to their relatives and friends on the outside. Two years in, they remain overwhelmingly grateful for the free communication, the improvements their families have seen in their finances and the quality of the relationships they have been able to maintain.

-

Read Next:

“Now we get the six 15-minute calls a day, [there are] many days that I just gab with my mom as she enjoys her morning coffee gossiping like if I was home and calling her,” wrote June Seger, who has been incarcerated since 2002. “It has helped not only with her chronic depression and loneliness, but mine also. I feel that this free calls has been a godsend.”

However, the system has its challenges.

Interviews with advocates and emails that The 19th and Connecticut Public received from incarcerated people revealed that those in prison are not always allowed to make use of their allotted 15 minutes per call. One of the main reasons is that the quality of the connection is so poor at times that the call either drops or they can’t hear what the other side is saying. Several people in prison also complained that correctional staff sometimes cut off their calls intentionally.

Over five months of reporting, The 19th and Connecticut Public reached out to the Connecticut Department of Correction more than 15 times by phone, email, Freedom of Information requests and an in-person visit to ask for data, comment and information about the way the free prison communication operates. Officials provided some of the requested data and policies, but declined to speak on the record for this story.

The free prison email and phone calls came too late for Tracy Shumaker and her three kids. She spent 18 years at Connecticut’s all-women York Correctional Institution and was released in June 2022, less than two weeks before the changes to communication went into effect.

Her kids were 2, 7 and 12 years old when she was arrested. When she got out of prison, they were 20, 25 and 30.

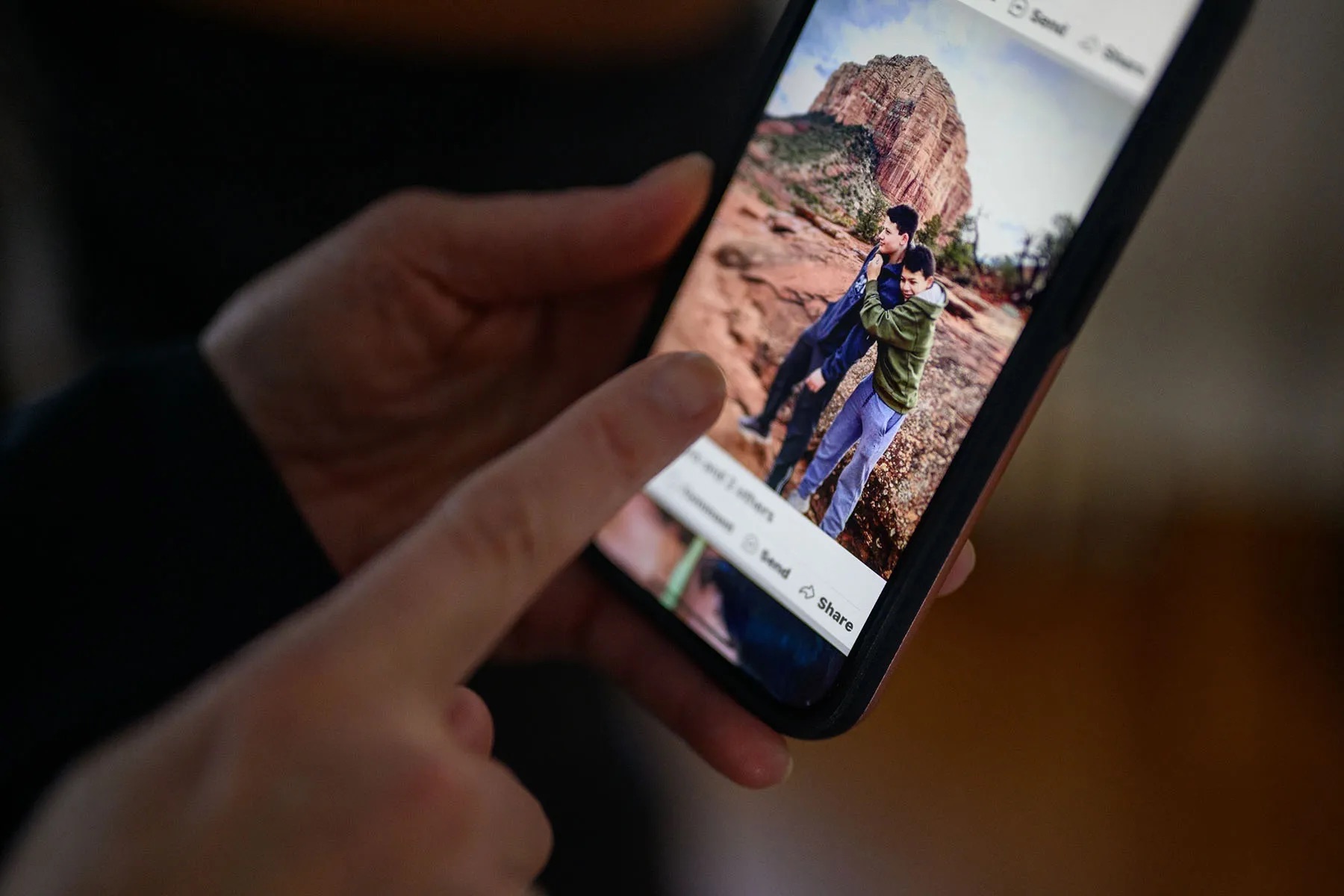

In April, at her apartment in New Britain, Connecticut, 11 miles outside of Hartford, Shumaker rummages through a large plastic bin filled with photographs. Some of the images register experiences she lived, like a visit with her teenage daughter inside the prison. Other pictures — a small school portrait of her youngest son’s first girlfriend and another of her oldest son with his high school prom date — capture moments she pieced together from stories family and friends told her over two decades.

Shumaker said she tried her best to maintain contact with family from prison, but her mother and sister lived paycheck to paycheck and could only afford a single 15-minute call once a week or once every other week when money was tight. That could only do so much to keep Shumaker informed as life outside moved forward.

“My sister had extra mouths to feed because she had my kids. My mother is working just to make ends meet. And then you only get like two minutes with each of your kids because you got a 15-minute phone call. When you got three kids and a mother that is crying, it’s hard,” Shumaker said.

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

As the years went on Shumaker felt distance growing between them. Soon, her children resorted to saying a quick “Hey mom, what’s up?” before passing the phone to another family member. After everything her kids had been through surrounding her incarceration, Shumaker said she did not want to force them to talk to her — even if that meant allowing them to drift apart.

At one point, her daughter played lacrosse in an athletic complex next to York Correctional Institution. On days that she could hear children playing on the fields, she wondered if her daughter’s voice was one of them.

As soon as Shumaker was released from York, she started to work on mending her relationships. Though things have been improving, the process is slow and complicated. There’s anger, resentment and also general discomfort to work through. After the years of lost time, Shumaker has had to get to know her now-adult children again.

“We have to make room for each other. They lived this life for 20 years. I’ve lived a solitary life for 20 years behind bars. So I can’t go, ‘OK, now Mommy’s home.’ I’m just letting it naturally become what it is,” she said.

Shumaker thinks that if she and her children could talk on the phone for free while she was in prison, things might have turned out a little differently today. The relationships with her kids could have been stronger.

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

Nearly 60 percent of women in U.S. prisons are mothers, and the separation is devastating for both them and their children. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classify having an incarcerated parent as an “adverse childhood experience,” a traumatic event that can put children at risk for chronic health problems, mental illness or substance abuse during adulthood.

Limited phone calls or visits can worsen these issues, but the cumulative cost often leaves families with limited options, said Aileen Keays, manager of the CT Children with Incarcerated Parents Initiative at the University of Connecticut.

“Families were talking to us about having to make a choice about keeping the lights on, or keeping money on the phone tab so that their loved one can call them every day,” she said. “These kids, they worry so much about their parents, so these phone calls are just essential.”

Then, there’s the profound mental health toll the isolation takes on mothers. Most women enter custody with a history of trauma like domestic violence or sexual abuse. They also experience higher rates of serious mental illness that put them at more risk of psychological harm behind bars.

“When I first arrived here at York I did not talk to anyone via telephone. All my contact was through mail and visits,” wrote Vanessa Ortiz, who has been incarcerated in Connecticut since 2010 when her son was 3 years old.

Her family could not afford the calls, she added. “So many women including myself have tried to take their lives because the emptiness one feels is crucifying.”

Worth Rises set their sights on reform in Connecticut after state Rep. Josh Elliott met Tylek at a conference in 2017 and suggested working together. At the time, Connecticut had one of the most expensive prison phone call rates in the country, $3.65 for a 15-minute in-state call. Elsewhere in New England, the rates were $1.50 in Massachusetts, $1.35 in Maine, $0.71 in Rhode Island, $0.59 in Vermont and $0.20 in New Hampshire.

In 2018, Connecticut families collectively paid about $13 million in prison calls to Securus. Of that amount, the company had an agreement that allowed the state government to take about $7 million.

While having conversations with Elliott, Worth Rises was simultaneously building momentum on free prison calls in cities — first New York in 2018 and then San Francisco in 2019. For the first statewide campaign in Connecticut, Tylek said it was important to work with a network of local organizations and helpful to have Elliott as a partner to help navigate the legislature.

“Every single person we talked to had a very specific individualized concern that we needed to address,” Elliott said about their meetings with Democratic and Republican lawmakers. “We wanted to win over every single person that we could.”

They pointed to research indicating that consistent phone calls and visits during incarceration improves the success of reentry into society after prison and reduces recidivism. They highlighted that incarcerated people might have fewer clashes with each other or with correctional officers if they are able to talk to their loved ones regularly over the phone.

The most powerful argument to lawmakers, however, came from the families themselves, who are most commonly the ones paying for prison phone calls — and 87 percent of those footing the bill are women, Tylek said.

“That's what typically moves the most number of people, because regardless of where you are in partisanship, everybody believes in family and everybody believes in children,” Tylek said.

In June 2021, free prison calls became law. The rollout began a year later.

“Hello, this is a prepaid call from … an incarcerated individual at Garner Correctional Institution. This call is not private, it will be recorded and may be monitored…”

Denise Paley listens patiently to the familiar automated message that she’s heard nearly every day for four years. She follows the prompt and presses 1 on her cell phone.

“Thank you for using Securus, you may start the conversation now.”

“Hi honey, how you doing?” Paley says to her 22-year-old son.

She pauses, listening. “Okay, were you able to get any Tylenol?”

Her son has been feeling sick for the past few days and Paley wonders out loud if it could be a stomach bug. They then move on to other subjects. She asks him what genre of books he wants her to send him. He asks her whether he’ll ever go to college. She reassures him that he will. At 15 minutes sharp, the call ends.

“It just cuts off,” Paley says.

These calls have become the norm for Paley and her oldest son, but they never actually feel normal. He has been incarcerated — without a conviction — since 2020. His case stalled while he underwent evaluations at a state hospital, and he received a diagnosis of schizophrenia only after his lawyer hired an outside organization for a medical evaluation. Paley said there have been other setbacks that have slowed down her son’s case.

In 2022, a judge ruled that Paley’s son was competent to move forward with legal proceedings. Last August, he rejected a plea deal that came with a 13-year prison sentence. He now awaits a trial date, hoping that his mental health diagnosis, past history of nonviolent behavior and time served in prison will help his case, Paley said.

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

Phone calls have been critical for Paley, her husband and their youngest son, who is 18 years old, throughout these years of stress. She knows they are more privileged than most families. The cost of prison calls was never prohibitive for them and she has been able to talk to her older son most of the days he has been behind bars, even before the calls were free.

But there are times when the calls are less consistent. The COVID-19 pandemic started soon after Paley’s son entered custody, bringing with it a surge of infections and deaths among incarcerated populations around the country, lockdowns in and outside prison, and restrictions on visitations and calls.

Paley’s son was having hallucinations and needed treatment, but it took years for medical providers to find a combination of medications that worked. Like many incarcerated people with serious mental illness, he spent stretches of time in what correction officials call “restrictive housing,” which is essentially another term for solitary confinement.

State correction officials, including those in Connecticut, claim to use solitary confinement not only as a form of punishment, but also as a way to protect incarcerated people. This practice disproportionately affects those with mental illness and transgender people who face unique threats to their safety. A 2023 report by the Connecticut Sentencing Commission found that 39. 7 percent of unsentenced people like Paley’s son in the state have “active” mental health disorders compared with 25.8 percent of those who are sentenced.

The Connecticut Department of Correction’s policy for restrictive housing does not mention phone call or email access. Officials did not answer reporters’ questions asking whether phone privileges are taken away from people in solitary confinement.

A 2022 law meant to reform Connecticut’s use of solitary limits the number of days a person can be kept in isolation. It also requires that people in restrictive housing receive a minimum of two hours outside of their cells, including an hour of recreation time. This should include time for phone calls.

Paley said, however, that during one of her son’s recent times in solitary confinement, she did not hear from him until he returned to the general prison population five days later. According to Paley, department officials told her that he declined to leave his cell to shower or make calls. Her son told her that he was not allowed to.

“Part of the reason he calls me every day is because he knows that we are just so worried,” she said. “So where else is my mind gonna go? That he’s dead, that he's injured, that something happened. That's where my mind goes.”

For families with fewer financial resources than Paley’s, these periods of silence and uncertainty were much more common before Connecticut prison calls became free. Incarcerated people disproportionately come from low-income backgrounds. A 2018 report from the Brookings Institution found that boys who grew up in families earning less than $14,000 a year were 20 times more likely to be imprisoned in their early 30s than children from wealthy families.

The inability to pay for communication often left families in the dark, sometimes for years, about what was happening inside the prisons, and whether their loved ones were safe inside.

After decades of outcry from activists about the harms of corporate influence in the carceral system, Connecticut was the first state to offer a blueprint for taking on the privatization of prison services nationwide. Unlike other states, Connecticut and Massachusetts are the only ones that cover costs for all prison communication — phone calls, video calls and electronic messaging. California, Minnesota and Colorado have only made prison phone calls free.

Official state data show the impact of the change in Connecticut. In June 2022, one month before calls became free, there were 600,656 from people held in correctional facilities throughout the state. In the first month the law went into effect, that number increased by 128 percent, to 1,373,276 calls, according to state figures provided to The 19th and Connecticut Public. There were 1,182,274 calls in January, the most recent month for which figures are available.

The state also began providing individual tablets to all incarcerated people in 2021. The tablets can be used to make calls, send emails and access some educational materials for free, and to purchase a limited number of movies, games and music.

Nationwide over the past five years, Securus has distributed 600,000 tablets and spent $600 million to install closed wireless network access and security protections at correctional facilities. In an email, Jennifer Jackson-Luth, senior director of communications for Securus’s parent company Aventiv Technologies, said the tablets “help bridge the digital divide.”

The work of building out infrastructure for emails, phone and video calls inside prisons is more complex than traditional communication services, Jackson-Luth added, but she did not provide details on those complexities.

The incarcerated people who wrote to The 19th and Connecticut Public said it is easier to make calls from a tablet than to have to rely on the two or three landline phones for them in prison. Even with the flexibility they offer, many advocates view the tablets as another opportunity to overcharge for otherwise inexpensive services, like e-books or music.

The state negotiated a three-year contract with Securus — down from its previous seven-year contract — that runs through August 2026 at a rate of $30 per incarcerated person each month for phone calls and $15 per person each month for emails. Tylek believes the state could have negotiated a less expensive rate. However, she said having a shorter contract enables state officials to change telecom vendors if needed.

These costs are now supported by $9.5 million taken from the state’s general fund in fiscal years 2024 and 2025 — $6 million to cover phone calls and $3.5 million for electronic messaging. An additional $888,011 per year goes toward adding 15 additional correctional officers.

(Ryan Caron King/Connecticut Public)

The state Department of Correction allows calls and messages during specific windows of time throughout the day. On paper, people are permitted to speak by phone for up to 90 minutes per day, but that time is broken up into six 15-minute calls. (That specific structure of capping at six calls is not part of Worth Rises’ design, Tylek said.)

In practice, incarcerated people and advocates who work with them told The 19th and Connecticut Public that people in prisons are not credited for any minutes they do not use if a call drops from poor connection or organically ends before the 15 minutes allowed. Landline phones in prisons have long standing connectivity issues that make for poor, barely intelligible calls. The new tablets have their own connection problems that also lead to dropped calls.

“It's an implementation error more than anything else,” Tylek said. “Six 15-minute calls is what people are allowed by the DOC. That adds up to 90 minutes. But if you make a phone call, and you're only on the phone for five minutes, that counts as one of your calls. In theory this shouldn't be the case because it means you still have 10 minutes left.”

-

Read Next:

Incarcerated people also say that prison staff sometimes purposefully cut off their calls before they reach the maximum time, and staffers withhold calls for a month or more when they want to sanction people.

“There is a daily hassle trying to call our loved ones,” wrote one incarcerated woman who asked for her name to be withheld from the story to avoid potential retaliation from corrections staff. “The staff have taken it upon themselves to withhold the wall mounted phones as a way to bully us into performing duties outside of our responsibility. According to the directive, the phone is to be available from 7:00 a.m - 10:00 p.m. The staff never comply with this directive.”

Overall, the incarcerated people that reporters emailed with said they would like to have their full 90 minutes of calls each day, stronger WiFi and larger windows of time to make calls and send emails. They also want more flexibility to add new numbers to the list of people they are permitted to call. Currently they can only change the numbers on their list at the beginning of the month.

Lewis said Connecticut still has a long road ahead to improve conditions for the roughly 10,500 people in the state’s prisons. Her work on this free prison calls bill broadened her understanding of these harsh realities, but it also gave her hope about the power of her voice and the collective action of her community.

“You get one win and then you see that, ‘Wow, that I could do this,’ and then you see so much more stuff that needs to be done. So you just go out there and you do it,” Lewis said, speaking about her advocacy work. “You want to make sure that your children and grandchildren, especially, have a different place to live than you did — a better place.”