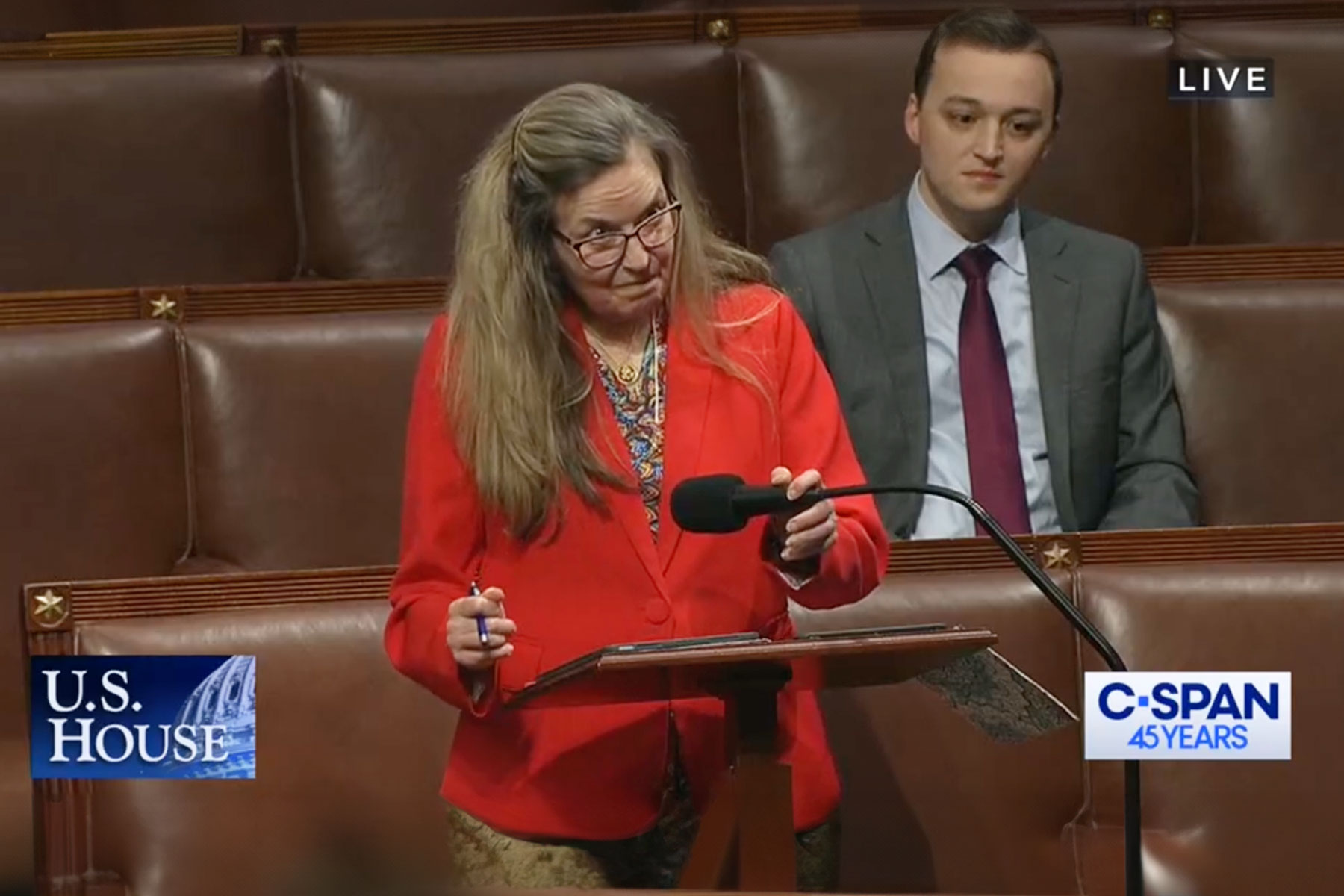

Last week, Rep. Jennifer Wexton made disability history by becoming the first member of Congress to deliver a speech using an augmentative and alternative communication device on the House floor. Wexton has a rare degenerative condition called progressive supranuclear palsy, or PSP. However, some in the disability community feel that the news coverage has missed the point, focusing on novelty without acknowledging Wexton’s actions in the deeper historical and social context of a world that is not built for people like them.

The speech was in support of a bill Wexton introduced to rename a post office in Purcellville, Virginia, after former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, the first woman to hold the job.

“The choice to use a text-to-speech device on the floor of the House of Representatives was a no-brainer for me. Despite my PSP condition which has impacted my ability to speak loudly and clearly, I want to keep doing my job and that means relying on this device to have my voice heard in Congress,” Wexton told The 19th.

The 19th spoke with disabled people who use augmentative and alternative communication similar to Wexton’s about how they felt in this historic moment and about the surrounding news coverage. They expressed joy, frustration and hope for a better future.

Augmentative and alternative communication, or AAC, covers a wide range of practices, from temporarily writing out requests while recovering from surgery to long-term use of the type of text-to-speech app Wexton relies on. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, an estimated 5 million Americans cannot rely on speech alone to communicate and would benefit from AAC.

India Ochs, 48, lives in Annapolis, Maryland. She has a speech disability and is a lifelong AAC user. In 2020, she ran for the Anne Arundel School Board. She didn’t win, but she still broke a barrier and is proud of her foray into local politics.

“I felt that was the right time, the best opportunity, to channel years of public testimony on school issues – and decades of experience in legal and legislative settings, leadership, education and human rights advocacy, and juvenile justice reform, back to the community I grew up in, to support not only my son, but ensuring the best education and safe environment for all the thousands of other students, teachers, and families,” Ochs said.

Ochs was pleased to hear Wexton using her AAC device on the House floor but has been frustrated with how news outlets have covered it.

“After thinking how great it was, my next thought was, why did they only play the segment where she talks about her illness? I want to hear what she actually was testifying on. Then when I went to find other coverage and hear her actual testimony, it got more frustrating with the number of times broadcasters used the word ‘inspiring,’” Ochs said.

The word “inspiring” is complicated or even insulting for many people with disabilities, including Ochs. The late disability activist Stella Young described her frustration with being praised as “inspiring” for doing things as simple as going to the grocery store.

Young coined the term “inspiration porn” to describe how describing disabled people as “inspirational” can be objectifying.

“I use the term porn deliberately, because they objectify one group of people for the benefit of another group of people. So in this case, we’re objectifying disabled people for the benefit of nondisabled people. The purpose of these images is to inspire you, to motivate you, so that we can look at them and think, ‘Well, however bad my life is, it could be worse. I could be that person.’ But what if you are that person?” Young said in a 2014 TEDx Talk.

Ochs also feels that many media outlets failed to understand that methods of communication used by people with disabilities, including text-to-speech software and sign language, should be considered as equal to spoken language.

“Any method a person communicates is their voice. Making the assumption that our natural voice is our only voice is ableist and demoralizing to every person that has spoken by speech app, sign language, pen and paper, etc.,” she said.

She added, “In a perfect world, coverage should have been about renaming the post office after Madeleine Albright.”

Jordyn Zimmerman, 29, lives in Hudson, Ohio. Zimmerman is the board chair for CommunicationFirst, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting and advancing the rights of nonspeakers like Zimmerman, as well as others who cannot rely on speech alone to be understood.

Zimmerman is autistic and uses an iPad app to communicate.

“Watching Rep. Wexton on the floor of Congress was incredible! She leaned into the alternative communication tools available to share on the House floor — normalizing tools and supports that people rely on every single day,” Zimmerman said.

Zimmerman said that she has been denied access to the House viewing gallery because she relies on her iPad to communicate. Electronics are currently banned, and she would have to give up her ability to speak to be allowed in.

The 19th called the House sergeant-at-arms’ office to clarify whether exceptions are made for disabled people like Zimmerman. The office confirmed that normally, electronics are not allowed in the viewing gallery and directed The 19th to the Office of Congressional Accessibility Services about accommodations for people with disabilities. The Office of Congressional Accessibility Services declined to comment.

We made it our business

…to represent women and LGBTQ+ people during this critical election year. Make it yours. Support to our nonprofit newsroom during our Spring Member Drive, and your gift will help fund the next six months of our politics and policy reporting. Can we count on you?

Zimmerman believes that such rules may discourage people who use AAC from running for office.

“Whether someone has a disability before or acquires one, similar to Rep. Wexton, we must design our spaces and policies to encourage the diverse thoughts that exist in our country,” she said.

endever* corbin, 38, lives in Portland, Oregon. The asterisk is part of their name. They are autistic and work part time peer mentoring in a program focused on health care for people with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

corbin was delighted by Wexton’s speech, describing it as “a little surreal” but “homey” at the same time.

“Hers is a voice I recognize as kin. It was the setting that was surreal. Because normally we would not be allowed there, or at least would not be expected to be there. So there was a sort of happy flapping feeling — wow, someone like me! On TV at all, let alone on C-SPAN!” corbin said.

They are optimistic about how technology and increased acceptance of at least some disabilities will improve.

“I do think there will be more and more assistive technology users who serve as elected officials. For example I remember Senator Fetterman using captioning to support his auditory processing on the floor recently, too. Disabled people make up a huge portion of the population, and the technology available to us only continues to expand in abilities and decrease in expense as time goes on, so it’s entirely reasonable to me that there will be more assistive tech of various kinds in Congress in the future,” corbin said.

However, corbin is less optimistic that this increased acceptance will extend to all people with disabilities – particularly those who use AAC like they do.

“AAC specifically – especially when used by people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities who haven’t ever spoken with mouthwords enough to gain credence as whole human beings? That feels harder to hope for,” they said.

Wexton is aware that the response to her manner of communicating has been somewhat exceptional and hopes that the same grace will be extended to other Americans who use AAC.

“I’m very grateful that I’ve received nothing but generous accommodations since my diagnosis, but I recognize that is often not the case for too many Americans facing similar challenges in the workplace and in their everyday lives. I hope that seeing AAC being used on the House floor helps more people understand that just because my words may be heard from a device doesn’t mean they’re any less mine or any less important to hear,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated what AAC stands for. It is augmentative and alternative communication.