New Hampshire state Rep. Ellen Read remembers how trapped she felt as an 18-year-old in her native Tennessee, enduring the physical and emotional toll of an abusive relationship.

The abuse Read suffered — which included being held captive in an apartment for days and hit by her abuser’s car — lasted years after she left the relationship, while her abuser stalked her.

In 2016, Read won election to the New Hampshire House of Representatives. That same year, she recalled to Stateline, her abuser died by suicide after 16 years of prolonged stalking.

Now, a bill authored by Read would allow victims of domestic and sexual violence — including stalking — to break their rental lease agreements early if they provide a police report or are in the process of obtaining documents such as a protective order following an incident.

“My hope is that this increases the boldness of people living in these abusive situations and that they know if they leave, there will be a path forward for them and they won’t be forced to stay with their abuser or at the home they were abused in,” said Read, a Democrat. The bill has been sent to Republican Gov. Chris Sununu after passing both chambers.

The pandemic lockdown that began in March 2020, coming alongside the nation’s worsening housing crisis, has prompted state lawmakers to help victims of assault who are struggling to move away from their alleged abusers. Domestic violence incidents in the United States increased by 8.1% in the months following the imposition of pandemic lockdown orders in 2020, according to a 2021 report released by the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice, a group launched by the Council on Criminal Justice, a think tank.

More than a dozen states have passed measures in the past five years bolstering rental protections for survivors by allowing them to break their leases if they provide evidence of stalking, sexual assault or an abusive domestic relationship. Many of those laws, which were enacted or strengthened during the pandemic, give victims more leeway in how they can document the abuse.

Many cities and states are looking to help survivors with new housing in other ways, such as by obtaining grants to develop transitional housing or offering housing vouchers to victims.

“It is deeply traumatizing and harmful to force survivors to continue to live in the same home where the harm occurred,” said Kate Walz, associate director of litigation at the National Housing Law Project, an advocacy group that trains legal services organizations. “It can retraumatize and compound the harm over years, if not decades.”

Several states are addressing the issue this session. Efforts to add early lease termination laws for victims in Ohio, Pennsylvania and South Carolina have yet to either make it past committees or both chambers.

While Pennsylvania’s effort to pass these protections statewide has stalled, the Pittsburgh City Council approved a bill in October that requires landlords to allow domestic abuse victims to exit their leases without penalty, and also change a tenant’s locks upon request, though at the tenant’s expense.

Nicole Molinaro, president and CEO of the Women’s Center & Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh, one of the country’s first domestic violence shelters, called the legislation “monumental.”

Molinaro hopes the state will eventually enact similar protections. She said that the trauma of domestic and sexual violence can be “crippling,” and that some victims may need to leave their neighborhood or cities altogether if their abuser also has roots there.

“A driving factor for survivors of domestic violence is making sure that there is somewhere safe for them to go,” Molinaro told Stateline. “And that often means a survivor cannot move back to the neighborhood they were in if the abuser still has connections there.”

The post-separation journey

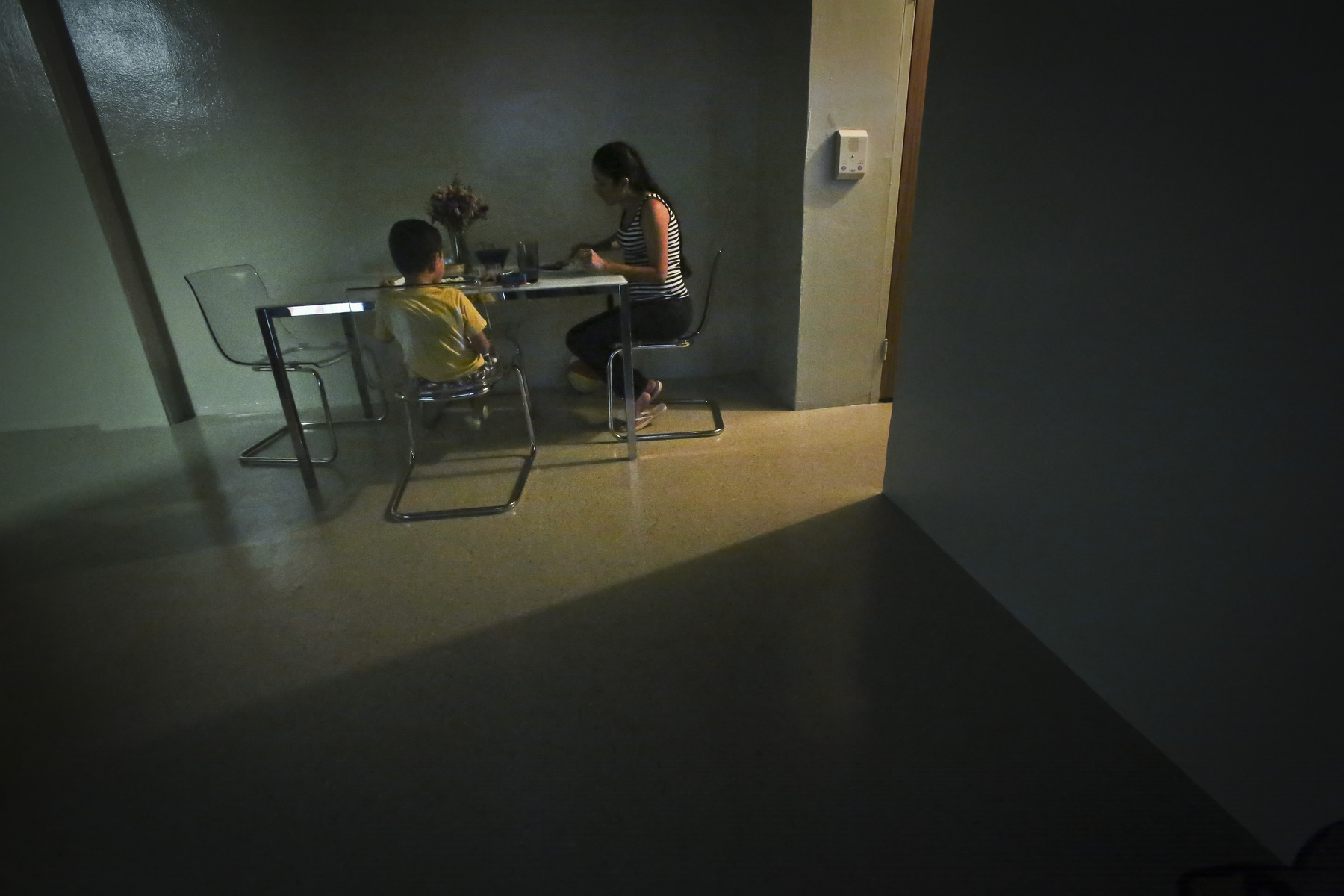

When New York City resident Stephanie Woodbine and her adolescent daughter left a two-year abusive relationship in 2017, she wasn’t sure where they were going to live.

Woodbine told Stateline that on top of emotional abuse, she also suffered economic abuse — a form of abuse that New York City last year officially recognized as domestic violence. She found housing, then was evicted after losing her job.

“I really didn’t have a lot of money to pay for housing because the mental trauma made it hard to live a normal life, keep a job,” Woodbine said.

She didn’t qualify for the domestic violence shelters because she wasn’t in an “active domestic violence situation,” she recalled, so she stayed in hotels and lived a life of “hidden homelessness” with her daughter.

“There are so many decisions that make leaving any abusive situation hard, but when you leave you find out just how hard it is to survive when you feel your options are limited,” said Woodbine, who eventually received an emergency housing voucher and has secured permanent housing.

“There’s a lot of post-separation abuse that is also contributing to survivors’ instability and their mental trauma,” added Woodbine, who now sits on the advisory council to the Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence. “It’s why we want to expand protections for survivors post-separation, and that includes providing permanent housing.”

Intimate partner violence is a major driver of homelessness, and researchers have found that housing is among the most common needs for survivors. Currently, 10% of shelters and transitional housing are targeted to domestic violence victims and their families, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

As the U.S. Supreme Court considers the constitutionality of homeless camping and outdoor sleeping bans, cities that have passed bans argue that outside encampments are dangerous not just for the public, but also for people staying there.

But Walz, of the National Housing Law Project, fears that if these bans are deemed constitutional, they’ll have a major impact on women and children fleeing domestic violence situations.

“Gender-based violence is both the cause and consequence of housing instability. Housing instability increases your risk of it, and housing instability comes as a result of it,” said Walz. “If we don’t recognize that and craft our policies to be responsive to it, we are guaranteeing continued violence and increase of it.”

More cities are working to include housing as a key service for survivors.

Woodbine credited city-based nonprofits for navigating her through the emergency voucher process — an intimidating process for those in need of housing.

New York City is hoping to provide such protections and, most importantly, housing through a pilot program funded with a $300,000 grant — from the NYC Fund to End Youth & Family Homelessness — that aims to help 100 families affected by domestic violence find homes.

Saloni Sethi, acting commissioner of the Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence, told Stateline that the pilot program addresses the need for safe and stable housing for survivors in a place where secure housing can be scarce.

“Survivors are often sort of faced with this really impossible choice of, ‘do I give up my own safety or do I destabilize myself and my entire family by leaving home?’ … We anticipate this pilot can finally provide that stable, fresh start,” Sethi said.

Many cities and states have become more intentional about building or reserving housing for survivors, with increasing support from the federal government. Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women awarded 81 grants, worth $43 million, to programs offering housing for six to 24 months for survivors.

Breaking the lease

If Read’s bill is signed by Sununu, New Hampshire would become one of 40 states to have early rental lease termination protections for victims of domestic or sexual abuse.

In post-lockdown years, Oklahoma passed early termination laws for domestic violence victims. Utah amended its early termination law in 2023, reducing the termination fee from 45 days of rent — one of the highest in the nation at the time — to a month’s rent.

Read’s bill, which she based on a similar one in Tennessee, stalled in committee when she first introduced it last year.

During early debate, New Hampshire landlord groups raised concerns about the financial burden they carry when tenants break their lease early — a position that irritated Read.

“Nobody will say in today’s society here that they are in favor of domestic violence,” Read said. “But put your money where your mouth is when it comes to allowing them to make that decision to exit their lease early even at a financial loss, or else it’s just lip service.”

But every time a new tenant comes in, it costs money to clean up and turn over the home, said Nick Norman, a real estate owner who serves as government affairs chair for the Apartment Association of New Hampshire. The bill’s original language also could have left a landlord responsible for things left behind, including damages.

The legislation now on Sununu’s desk is “drastically different,” Norman said. “The housing provider advocates and tenant advocates came together as we usually do to find a solution that works best for both parties.”

Read likewise credited the Senate for adding measures that would make qualifying for an early termination lease easier.

Some states, including Kansas, North Dakota and Utah, may allow landlords to charge fees or forward payment of rent for breaking the lease early in cases of intimate partner violence. And many states require documents from an outside source, such as a police report or court protective order.

Many landlords see such requirements as a necessary step in good faith to break a lease early. However, Walz thinks that these requirements are a barrier for survivors, given how underreported domestic and sexual violence is and how hard it can be for victims to obtain a report without escalating violence from their abuser.

“First and foremost, we must believe survivors. This means in action taking their own stories and experiences to be true and not requiring any form of third-party proof,” Walz said.

“Assumptions, stereotypes and bias — towards not believing survivors and perceiving that it could be made up in order to exit a lease — play into state policy responses and often result in a litany of requirements, including orders of protection, police reports, third-party statements,” she said.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected]. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

Recommended for you

From the Collection