This AAPI Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

The Asian American and Pacific Islander community is the fastest-growing racial group in the United States, growing over four times faster than the total population. Despite this tremendous growth, it is one of the most understudied racial groups in the country, both in terms of government data collection and private polling.

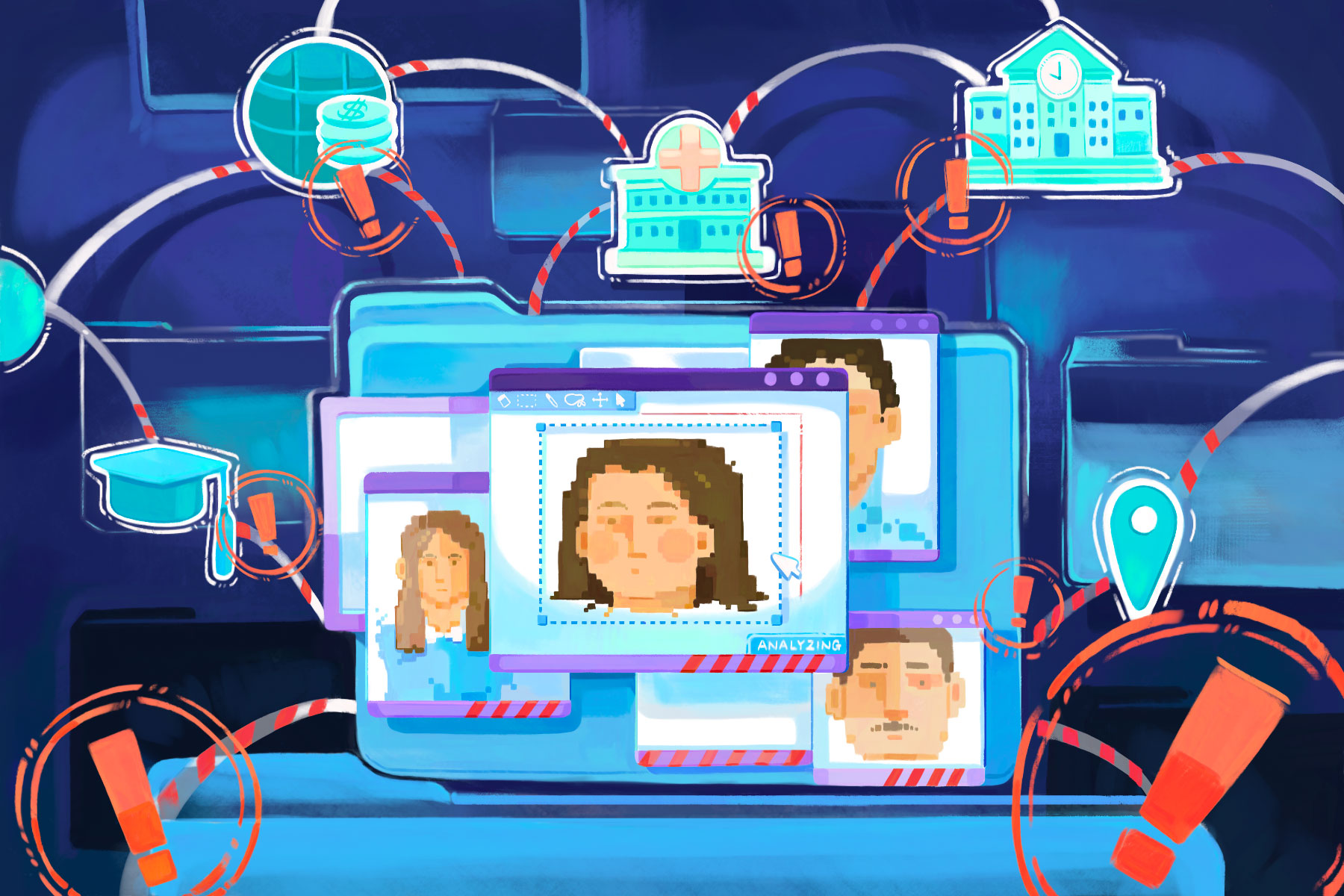

Many polls and surveys provide only one checkbox to represent all Asian-American people, even though more than 20 different Asian ethnic groups live in the United States. And this has wide-ranging consequences for everything from medicine to voting patterns.

When it comes to health, it wasn’t until researchers analyzed disaggregated data — data sorted into smaller ethnicity categories — that they found that breast cancer is a more prevalent cause of death for Asian Indian and Filipino women than Chinese, Japanese, Korean or Vietnamese populations. In politics, 6 in 10 Asian Americans identify as or lean towards the Democratic Party. When looking at the disaggregated data, however, researchers found that Vietnamese Americans are the exception, with the majority voting in line with the Republican Party. This increased understanding of the AAPI community can inform policy decisions that have historically ignored whole ethnic groups by lumping all Asian Americans into one category.

But that may be about to change. The federal government announced in March that it had updated its race and ethnicity standards in response to “large societal, political, economic and demographic shifts in the United States,” according to the Office of Management and Budget. Within five years, all federal agencies that collect demographic data will be required to start collecting more detailed race and ethnicity information beyond the current minimum categories, which represent the six largest Asian population groups in the U.S.: Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese.

AAPI Heritage Month: Leaving our mark on American democracy

This story is part of our AAPI Heritage Month coverage. This month, we’re telling the stories of people who are carving out space as the nation gains new citizens and another generation of American-born AAPI people comes of age. Explore our work.

“If you collect data with just the Asian checkbox, you’re not really understanding the diversity in the community and outcomes ranging from poverty, health, education, housing and so many things,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, the founder and executive director of AAPI Data. “We just scored a major win.”

For decades, Ramakrishnan has been pushing the federal government to disaggregate ethnicity data. AAPI Data was founded in 2013 to produce accurate, consistent and comprehensive data on the AAPI community.

“This is a success story: Academics coming together with community organizations and working with members of Congress to get this across one finish line,” he said of the new standards. “But a new race has begun.”

Ramakrishnan said his organization celebrated the announcement, but a few weeks later issued three recommendations on how to quickly and effectively implement a rollout. First, the organization demanded that the chief statistician of the United States publish a data disaggregation inventory of all current federal agency data. Then, the chief statistician must create a centralized, coordinated body to provide technical assistance to agencies as they move to comply with the new standards. And lastly, there must be a formal mechanism to receive community input and expertise from researchers who work in data equity.

The government standards were initially developed in 1977 to provide consistent data on race and ethnicity across federal agencies. At the time, this data was used extensively to monitor the enforcement of civil rights, such as in employment, voting rights, housing and mortgage lending, health care services and educational opportunities.

The standards were revised in 1997 in response to criticism that the minimum race and ethnicity categories no longer reflected the country’s increasing diversity, immigration and interracial marriages. In total, the standards recognized five minimum categories for race — American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and White — and two categories for ethnicity. The revision resulted in distinguishing “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” as two separate race categories and changed the term “Hispanic” to “Hispanic or Latino,” referring to ethnicity. Notably, respondents were also able to check multiple boxes for the first time, allowing the government to collect multiracial data.

These standards remained unchanged until 2024. Now, race and ethnicity information will be collected using a single question in which respondents can select multiple categories. Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) will be added as a new category, separate and distinct from the White category. And federal agencies will be required to collect more disaggregated ethnicity data. For example, instead of just providing “Black” as a designation, federal forms will also have to include options to identify as African American, Jamaican, Haitian, Nigerian, Ethiopian or Somali.

But not all data comes from the government. Private pollsters play an important role in surveying demographically representative samples of the population to better understand public sentiment — and how they collect and sort data is not bound by federal standards.

They face significant challenges, particularly when polling Asian-American communities, which make up about 6 percent of the national population and an even smaller share of voters. For one, it is expensive to survey a group large enough to include a representative sample of Asian Americans. A survey of 1,000 adults would typically include about 62 Asian respondents. Such a small number isn’t likely to be representative of Asian Americans, much less different ethnic groups.

We made it our business

…to represent women and LGBTQ+ people during this critical election year. Make it yours. Support to our nonprofit newsroom during our Spring Member Drive, and your gift will help fund the next six months of our politics and policy reporting. Can we count on you?

The second major obstacle is language. About two-thirds of Asian Americans speak a non-English language in their homes, so pollsters who want to reach them often have to invest in surveys written in different languages, translation fees or translators to conduct interviews.

Pew Research Center is one of the few organizations with the resources to overcome these obstacles. Neil Ruiz, the head of new business initiatives at Pew, has led a multi-year and multilingual comprehensive study of Asian Americans — the largest nationally representative survey of AAPIs to date. Launched in 2021, the project also involved 84 focus groups conducted in 18 different languages, moderated by members of specific ethnic groups.

“This took a lot of work,” Ruiz said. “Just to give you a perspective on why a lot of other organizations have a challenge in doing this, we had to mail over 216,000 mailings with $2 bills in them [as an incentive to complete surveys]. That yielded a sample size of 7,006 Asian adults. If you start adding that up, it becomes more than half a million dollars just with the mailings.”

Ruiz said this mega-project re-emphasized the importance of studying the diversity within demographic categories. Refugees are completely different from those immigrating as university students, and both are different from those coming into the U.S. as highly-skilled professionals.

“Being careful about examining within a major category provides the context and foundational facts for policymakers, storytellers, philanthropic organizations and foundations who should have a better understanding of Asian Americans’ unique needs and experiences,” Ruiz said.

Evangel Penumaka, the polling principal at the progressive think tank Data for Progress, said her organization doesn’t usually have the bandwidth to disaggregate data because they release national polling twice every week. Their polls are primarily used to inform politicians’ understanding of current public sentiment, so speed is their priority. The surveying team is typically only in the field for two to three days, compared to other large polls of Asian Americans, with teams that spend a month or so in the field to get a random sample that’s large enough to include various Asian groups.

“Since we focus on a universe of likely voters, we often don’t have enough [respondents] to show a cross tab for Asian Americans,” Penumaka said. “Ideally, if we had all the funding and time in the world, I would love to do a large Asian-American poll.”

However, as the Asian-American population continues to grow, along with pollsters’ understanding of their unique characteristics as voting blocs, Penumaka said policymakers will be more likely to invest in polling this community.

“The challenge of not disaggregating is we aren’t really looking at the disparities that exist by income or education,” Penumaka said. “There’s still kind of this model minority myth — that they’re a very highly successful population. But that ignores the income disparities, the health outcome disparities that exist within the community.”

According to the latest Pew data published in March, Asian Americans vary widely in their economic status and educational levels. About 1 in 10 lived in poverty in 2022, but looking at disaggregated data provides a better understanding of that situation. For instance, nearly 60 percent of the Asian Americans who live in poverty are immigrants and few speak proficient English. Looking even closer, Burmese and Hmong Americans have poverty rates nearly triple that of Filipino and Indian Americans.

Penumaka, who has a doctorate in political science with a focus on Asian Americans, said she thinks data collection among the AAPI community has “vastly improved” in recent years. She pointed directly to research efforts from Pew, AAPI Data and NORC at the University of Chicago, previously the National Opinion Research Center, which have made collecting disaggregated data about Asian American communities more affordable and streamlined.

As a result of a partnership between AAPI Data and NORC, which established a survey panel made up of members of the AAPI community, Ramakrishnan said they are now able to publish monthly surveys on political views, hate crimes, the economy and current events — broken down by ethnicity.

“This is a game changer,” Ramakrishnan said. “In the past, we rarely — if ever — had any opinion data on our community. For every presidential election since 2008, we’ve had opinion data. But what about all the things that happen in between?” Current opinion data is available now, he said, on topics like Israel and Gaza, the environment and reproductive rights. “We should know these things about our community, but the possibility for that did not exist before.”