This story was originally published by Wisconsin Watch.

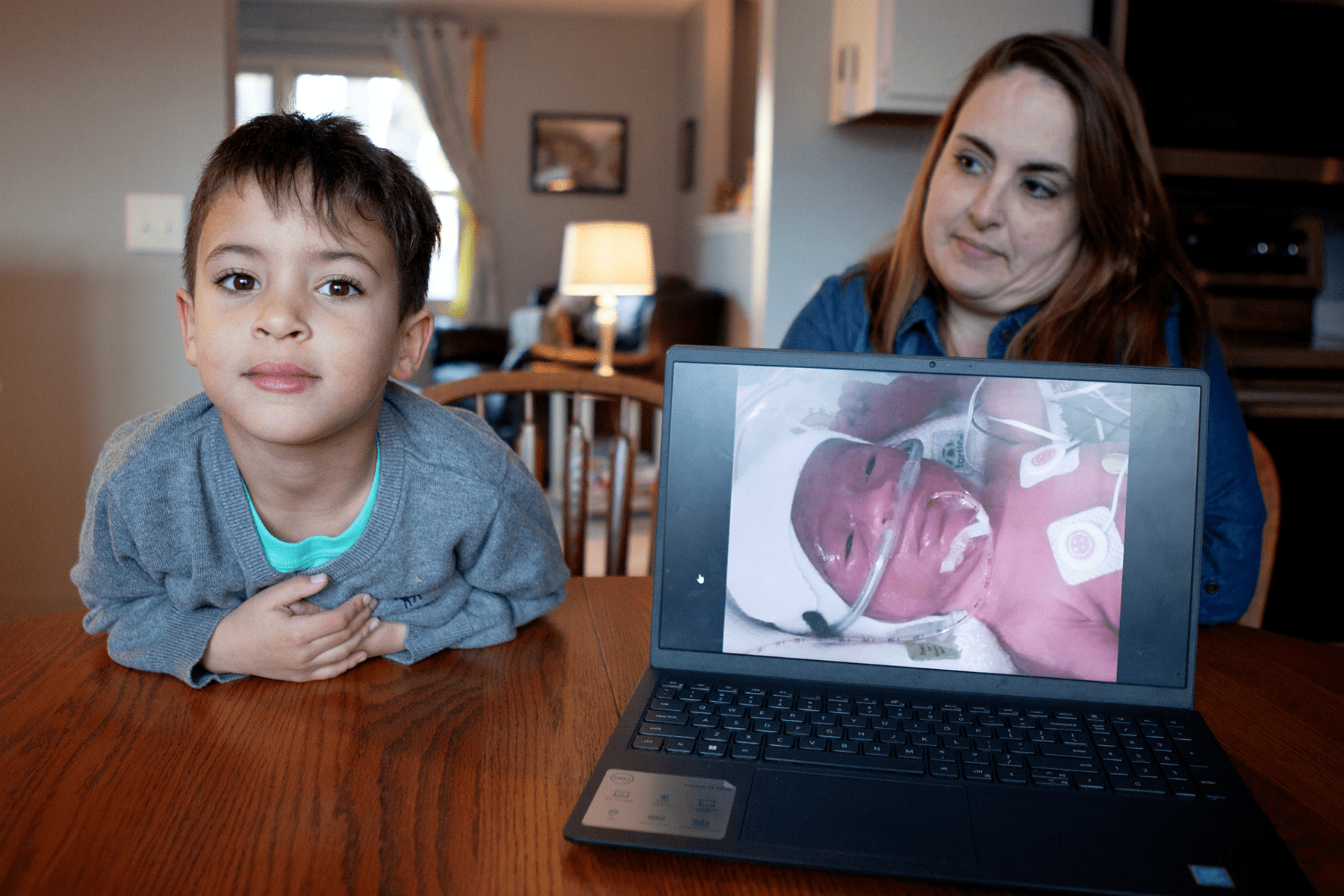

Emily Schmit didn’t expect to be a mother. She was told at a young age that she would likely be infertile, so when she took a positive pregnancy test in 2017 at age 30, she was overjoyed.

Then she went into labor at 28 weeks. Her son was born at just 2 pounds, 10 ounces, and spent his first 60 days in the neonatal intensive care unit.

To complicate matters, Schmit had recently left her job, qualifying her for the state’s BadgerCare Plus Medicaid program. In Wisconsin, where two of every five mothers give birth on the program, coverage stops for most recipients at 60 days. For Schmit, that meant leaving the NICU also meant the end of any postpartum care for her.

“They were just like, ‘Okay, well, we don’t want to see you. We want to see the baby,’” said Schmit, of Mount Horeb. “Instead of me having the opportunity to say ‘Hey, something’s not right,’ or ‘I need support,’ I didn’t even have that option because of the Medicaid program.”

Each year, at least 25 Wisconsin women die during or within one year of pregnancy, with less than a third occurring during birth.

Experts say extending the coverage period for people insured under Medicaid could help new parents with depression and other health issues and save lives among Wisconsin’s most vulnerable residents.

Yet the Legislature has turned down extensions with bipartisan support on multiple occasions. That includes a bipartisan bill that passed the Senate this session but the Assembly didn’t take up, making Wisconsin one of just four states without plans to implement a full-year extension.

Proponents: Extension would protect mothers’ health

Doctors say an extension would allow patients struggling with postpartum depression, anxiety, PTSD, schizophrenia, bipolar illness, substance use disorders and other mental health issues to continue therapy and medication amid sleep deprivation and stress.

“The year following a delivery is a very important year with huge life changes and where having adequate health care is absolutely essential,” said Dr. Lee Dresang, a family medicine doctor at UW Health and a professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Of the patients he followed with postpartum depression, “exactly zero magically got better at 60 days after delivery,” he said during a legislative hearing.

Maternal mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth, according to the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance, with suicide and overdose the top causes of death in the first year postpartum. Of the one in five women who struggle with maternal mental health conditions, 75 percent don’t receive treatment.

The emotions that manifest amid postpartum anxiety create a vulnerable time full of doubt and shame that can become overwhelming, explained Sarah Ornst Bloomquist, the co-founder of a Milwaukee-based perinatal mental health organization, Moms Mental Health Initiative. Thoughts might manifest in the form of “If you really wanted to be a mother, you wouldn’t feel this way,” “You are not a good mom,” or “Your family will be better off without you.”

Finding a therapist who understands those issues can take time. Amid stigma and a lack of resources, many people won’t reach out for help in the first place — and when they do, “one little deterrent will shut them down for good.”

While about half to 85 percent of people who were pregnant experience postpartum blues in the first few days to weeks after delivery, postpartum depression doesn’t usually emerge until two to three months after giving birth, though it may occur earlier.

Patients during pregnancy and in the postpartum period may also experience elevated weight and thyroid conditions, seizure disorders, high blood pressure disorders, diabetes in pregnancy and substance use disorders, among others, according to the CDC. Pre-existing chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes and heart disease may worsen during pregnancy or postpartum.

Lawmakers previously pushed for a 90-day coverage period. The 2021 state budget required DHS to request federal approval of a Medicaid plan to extend postpartum eligibility to 90 days, but the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in January indicated to DHS that it doesn’t intend to approve a request for a new demonstration waiver for a coverage period shorter than 12 months.

Contraception is “particularly an issue” that would benefit from an extension beyond 60 days, according to Dresang. More time would allow doctors to recommend waiting on patient-centered care, including IUDs and other birth control.

During the pandemic, enhanced federal funding for state Medicaid programs through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act ensured that postpartum individuals covered by Medicaid had continuous coverage, but that coverage ended last April. Dresang said having the benefits clients experienced was a “really essential and wonderful silver lining.”

Currently, when a mother’s Medicaid eligibility is redetermined after 60 days, eligibility is reduced from 306 percent to 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Parents whose income is above the federal poverty level, which is $1,703 per month in Wisconsin for a single mom with one child, must seek private marketplace coverage or lose insurance.

Parents who lose Medicaid eligibility may miss appointments and lose access to necessary treatment and medication, according to Amy Domeyer-Klenske, the chair of the Wisconsin section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“You have to do all of this paperwork and applications when you’re not getting enough sleep, you may be suffering from a postpartum mood disorder, you’re experiencing really huge bodily changes and health stressors and you’re newly a parent,” Domeyer-Klenske said. “It’s this high-risk time for parents that we’re asking them to reapply and re-qualify for insurance.”

Wisconsin is an outlier

People with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level receive pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage for 60 days postpartum under federal law, after which states determine coverage. Wisconsin sets the income threshold at 306 percent during that 60-day period, which is the highest level of all 50 states.

Following the 2021 state budget requiring DHS’ waiver request, the Republican-run Legislature again rejected Gov. Tony Evers’ attempts to include an extension in the budget this year.

But Congress’ American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 gave states a permanent option to receive federal matching funds for 12-month extensions. Forty-three states and Washington, D.C., have implemented a 12-month extension, and three are in the process. Wisconsin has not.

“We’re choosing to be in the lane of traffic that is most congested when the transportation people made an express lane available,” Domeyer-Klenske said, referring to waiting on the waiver as opposed to using the federal government’s state plan amendment option.

A bipartisan bill would put the state on a fast track there. The bill would have extended Medicaid eligibility for postpartum care from 60 days to 12 months. The Senate passed the bill 32-1 on Sept. 14, but the Assembly never scheduled it for a floor session before adjourning for the rest of the session on Feb. 22.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republian representing Rochester, has pointed out Wisconsin’s high Medicaid income eligibility limit. Vos in a June 13 Wisconsin Health News event said he doesn’t support a Medicaid postpartum expansion, adding that “we give away too much free stuff.”

“When you make a choice to have a child, which I’m glad that people do, it’s not the taxpayers’ responsibility to pay for the delivery of that child, right? We do it for people who are in poverty,” he said. “But to now say beyond 60 days, we’re going to give you free coverage, no copayment, no deductible, until a year out, absolutely not.”

Schmit said it was “extremely disheartening and frustrating” that Vos blocked the bill.

“It’s sad to think they are not allowing abortions and forcing women to raise children and won’t even support women and babies for the first year of life,” Schmit said.

Advocates have expressed frustration over the state’s lack of urgency. Wisconsin’s waiver proposal sought the shortest extension at 90 days.

Wisconsin Republicans also have refused to expand Medicaid coverage with federal funding available for the past decade under the Affordable Care Act. States that expanded Medicaid were significantly associated with lower rates of maternal mortality compared with non-expansion states, according to a widely circulated February 2020 study.

Like many health issues, postpartum complications affect women of color at a disproportionate rate. In Wisconsin, Black women are five times more likely to die of pregnancy-related death than white women, according to DHS, compared with 2.6 times higher nationally.

Jamie Daw, an assistant professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, said the crisis is on policymakers’ minds in a way it hasn’t been historically. Comparing it to how awareness about infant mortality rose as an issue in the 1980s, she said maternal mortality is “having its moment.”

“Half of these pregnancy-related deaths are happening in the year after birth, which is a huge rethinking of the entire problem. When it comes to maternal mortality, the traditional focus has been on pregnancy and childbirth,” Daw said.

Continuous coverage has bipartisan support

In the wake of the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, legislation increasing postpartum coverage has generally been bipartisan. Testimonials in support of the standalone bill included Pro-Life Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Catholic Conference, as well as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Kids Forward.

Sen. Joan Ballweg, a Republican representing Markesan, one of the lead authors of the bill, said she can’t think of any other issue with this much support from registered organizations.

“As a pro-life community, we think that this is an important piece to making sure that healthy moms make sure that babies are healthy,” Ballweg told Wisconsin Watch. “Science and health care have told us that we need to extend this coverage to make sure that we aren’t causing women to fall through the health care gaps.”

Daw noted that other states that historically have had lower Medicaid generosity like Missouri and West Virginia have implemented or are in the process of implementing a 12-month extension.

“Generally this has been kind of a bipartisan policy proposal, and it’s been accepted from red states and blue states, an unusual feat in the world of Medicaid policy,” Daw said.

Schmit said she thinks the bill hasn’t moved forward because of a stigma associated with Medicaid recipients. Schmit said her health concerns were often downplayed and that she was talked to condescendingly during her pregnancy.

“Regardless of your socioeconomic standing, you should still be able to be safe and secure,” she said.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.