The effects of personal religious belief are everywhere in politics, from the rallying sermons of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to Christian nationalists citing biblical justice when Roe v. Wade was overturned.

For queer people, R. G. Cravens argues, faith is more than a motivating factor — it can be a way into political engagement. His research shows religious LGBTQ+ people are more politically active than nonreligious LGBTQ+ people. In fact, religion often facilitated political activity, from congregations marching together at Pride events to organizing letter-writing campaigns to government officials.

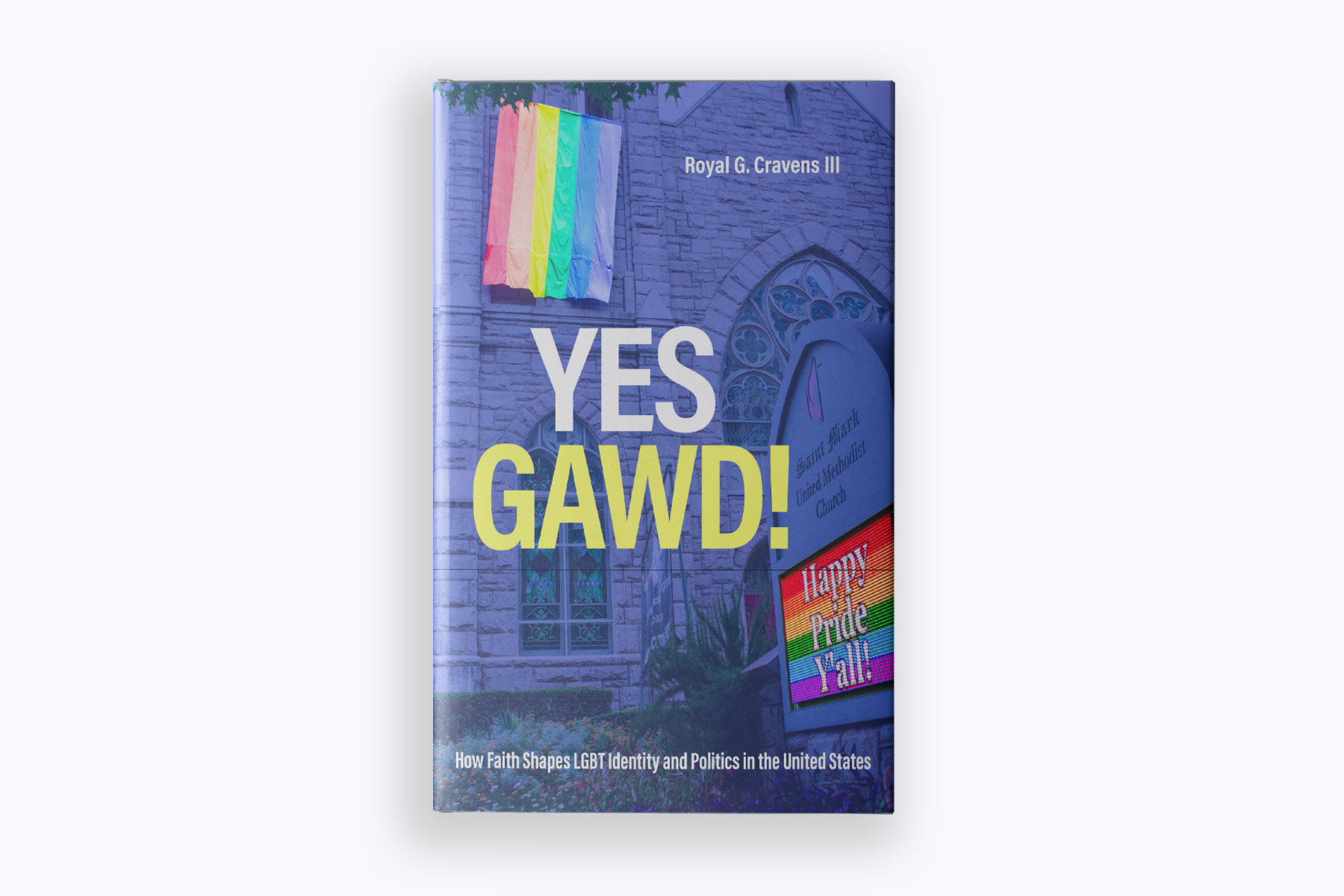

Cravens’ first book details his research on the intersection of queer and religious identity. “Yes Gawd! How Faith Shapes LGBT Identity and Politics in the United States,” released in January by Temple University Press, explores religiosity, identity conflict and how religious communities motivate political action for LGBTQ+ people.

Cravens draws on prior research on LGBTQ+ religious people, as well as two original surveys he conducted. One survey was a small pilot of 261 respondents and allowed for qualitative input on the role of religion, LGBTQ+ identity and politics. Much of the book draws from a survey Cravens conducted in 2021-2022 among a sample of 1,100 religious LGBTQ+ people. About half of LGBTQ+ people are not religious, according to 2020 research by the Williams Institute at UCLA — but that means half are.

When queer religious people come out of the closet, they don’t lose their faith — but many do change their religious affiliation, often to a more affirming tradition, i.e. one which actively welcomes LGBTQ+ congregants. This switch politically activated many of the queer people Cravens surveyed, showing the importance of queer religious movements to democracy.

Throughout the book, Cravens pays special attention to the differences between the experiences of religious queer people of color versus those of White queer people. Queer people of color in the survey were more likely to turn to political groups for support coming to terms with their gender identity or sexual orientation instead of religious or secular social groups. Queer people of color were more likely to say the LGBTQ+ community was hostile to religion, and Black LGBTQ+ people were more likely to avoid queer spaces due to religious discrimination.

The 19th spoke with R.G. Cravens about race, religion and how LGBTQ+ people are showing up for the 2024 election.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jasmine Mithani: Early on in the book you talk briefly about how all research questions are political. What politics stymied this kind of research on LGBTQ+ religious people until now?

R.G. Cravens: There were those sort of roadblocks to research into both LGBTQ experiences and religious experiences. For example, as a discipline, political science didn’t accept research questions designed around the experiences of LGBTQ people up until the 1990s — really early 2000s. Studying LGBTQ people and their effect on politics was really seen as too political, as too close to a partisan-type issue that quote, unquote, “legitimate” scholars would shy away from because it might be seen as biased. This continues to this day.

The idea was that the people who study [religion] are too close to the subject. They probably had family members who were ministers or came from religious families and so they had these personal connections. So in both cases, there was this idea that you’re too close to a subject, that you can’t make true scientific discoveries about it because your biases related to it are personal.

There were also just biases against the subject — homophobia, transphobia, those things are also pervasive in the disciplines of political science, for sure. For religion, it was the idea that religion is, I wrote about it in the book, “too epiphenomenal.” There’s too much spirituality to it to really understand it as a political phenomenon. There was a resistance to thinking about something that maybe was more difficult to quantitatively study.

It wasn’t considered that LGBTQ people and religious people actually affected political outcomes.

The book is structured around attitudes and action before and after LGBTQ+ people come out. What led to you focusing on this “inflection point”?

Well, there’s a lot of research that points to the importance of coming out as a defining moment, and my research certainly supported that. Coming out, though, is also a process. It doesn’t always happen all at once.

I did it this way also to recognize that we don’t have longitudinal data. We don’t have information from the same group of people over a long enough period of time to know how their actions or identities or behaviors or attitudes changed before and after they came out, politically speaking, or religiously speaking. I had to rely on this retrospective methodology where I had to ask people to consider: What was it like before you came out? And what was it like after?

It’s a recognition of the importance of coming out as a process that it affects you at different times, in maybe different ways. But also, it’s a recognition of the data limitations involved in studying LGBTQ populations.

Throughout the study you reference historical activism by religious LGBTQ+ organizations such as Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC) and Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). What kind of movements have you observed today?

MCC is still around, they’re definitely still an important institution for LGBTQ religion. There are lots of organizations.

There’s also a group called Interfaith Alliance, they have a faith for pride initiative, which I think is very important. Similar organizations to HRC like PFLAG and the National LGBTQ Task Force all have devoted some time to thinking about religion and its effect on LGBTQ people and families.

There are also a lot of religious organizations, we’re talking about what might be called affinity groups within some of the larger denominations. There are also those that exist as sort of affinity groups but within non-affirming denominations.

I believe that the number of religious affinity groups and the number of the larger, traditional LGBTQ activist groups who are increasingly conducting outreach to religious and LGBTQ religious folks is on the rise too.

The movement has existed as a way to, I mentioned in the book, hold America to its pluralistic and inclusive promises. It’s continuing in that direction by helping to democratize religious spaces, and helping to democratize political and social spaces to make room so that they are inclusive and work for everybody.

Resources for LGBTQ+ people of faith

- Affirmation (Mormon)

- Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists

- Dignity USA (Catholic)

- Eshel (Orthodox Jewish)

- Interfaith Alliance

- Kinship International (Seventh Day Adventist)

- Soulforce

- Queer Crescent (Muslim)

You pay particular attention to the different ways LGBTQ+ people of color relate to politics and the LGBTQ+ community compared with White LGBTQ+ people. What are some of the most fundamental ways race and racism change the way LGBTQ+ religious people of color take political action?

This was a very important question for me to think about. The ways that faith affects LGBTQ folks, I don’t think it could be answered without understanding and looking at the way that race intersects with each of these things.

It was really interesting to me how LGBTQ people of color were saying disproportionately that they were more likely to feel excluded from LGBTQ spaces because of their faith. And I think that’s important to consider that LGBTQ people of color, especially the Black LGBTQ folks that I’ve surveyed, are more religious on average. So understanding that faith is an important part of a community, and that community then feels sometimes ostracized because of it.

It’s important for folks in the movement to grapple with, because if we’re creating queer political spaces that don’t allow for acceptance or that don’t make space for important parts of the identities of other LGBTQ folks, then it calls into question the idea that the movement isn’t fully representing everybody, and that’s not an uncommon finding.

For me, this is a way to look at and analyze and critique the LGBTQ movement in certain ways and hold to account the idea that certain folks feel excluded and are excluded because of their faith.

That was true of some of the history that I looked at of LGBTQ people of color and faith organizing, where especially Black LGBTQ religious folks didn’t feel like predominantly White congregations were speaking to the needs of their sexuality, gender identity and their racial identity.

Just by nature of excluding folks, you change the way that the LGBTQ religious people of color take political action by making spaces less inclusive. You don’t have those voices, you don’t have that representation. It changes the very goals that your movement pursued. I think that’s an important way that that race, racism, have shaped this conversation.

Identifying with a marginalized group, like being LGBTQ, doesn’t make you immune from perpetuating other systems of oppression. And so it’s very important to have an intersectional movement to think about the ways that predominantly White LGBTQ institutions are perpetuating racism and critiquing that problem.

Not to spoil anything, but you end the book by saying LGBTQ+ people of faith have agency and power to make change in America. How are you seeing these dynamics play out in the 2024 election?

I published a piece for the Immanent Frame a couple of months ago that really spoke about this subject because it showed how — and what I think comes across in the book as well — LGBTQ people of faith can set a template for an inclusive politic that stands against the exclusionary narratives of things like white Christian nationalism, the things that want to chip away at our inclusive democracy, the things that want to chip away at pluralism in our country.

Religious LGBTQ people, the ones that I surveyed, have an inclusive ideal for what religion can be.

I’m not saying that religious LGBTQ people are perfect, that there aren’t issues or problems. But overall, the research that I’ve done shows that this inclusive faith stands up for the American ethos, the American value of pluralism and inclusive multiracial democracy and can help defend it.

And I think that’s what we’re absolutely seeing with LGBTQ movement organizations standing against things like book bans, standing against bans on public drag performances, for example. Things that would limit expression and things like free association, like these drag bans do, for example. LGBTQ religion stands against that exclusionary narrative.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of Soulforce.