Mary Dolan doesn’t live in Alabama. But she isn’t taking any chances.

Dolan, 35, lives in Tennessee, just one state away, and watched as an Alabama court halted in vitro fertilization until lawmakers let it resume.

IVF is legal in Tennessee, and as far as Dolan knows, there is no effort underway to change that. But she also knows that IVF, the most effective form of fertility treatment, likely offers her only chance of becoming a mom. She’s begun to worry: If an Alabama court made the regimen unavailable less than 200 miles away, then lawmakers in Nashville — who were quick to ban abortion when Roe v. Wade was overturned, and where Republicans run the legislature and occupy the governor’s mansion — could do the same thing.

So Dolan and her husband had a talk. They’ve done four egg retrievals so far; their frozen embryos are in a Tennessee clinic. They are planning one more retrieval. But if they can get off the waitlist, they’ll do their final retrieval and subsequent embryo cultivation in New York — a state where they feel more confident IVF will remain available.

It would offer a tiny bit of security when so little feels in Dolan’s control. Already, she feels like they’ve sacrificed so much: leaving her job in education to work in a warehouse return center that offered fertility benefits, postponing removal of the lead paint in their home to save up for all the medical bills. Estimates of the average cost of just one IVF cycle run anywhere from $12,400 to closer to $25,000 — and patients can require multiple cycles to get pregnant. On top of that, embryo storage can cost $1,000 a year or more.

Medicaid, which insures low-income people, does not cover IVF in any of the 50 states or Washington, D.C. Only 14 have laws requiring private insurance to do so.

“My husband and I feel like we’ve put our lives on hold in so many ways to try to create embryos and hope we can have a child someday,” Dolan said. “Not only do we have to worry about maybe an embryo transfer doesn’t work or it doesn’t survive the thaw or things like that, but there’s also this worry of: What if a ruling comes out that prevents us from using our embryos, or the clinics close down?”

For IVF patients in states that have moved to ban or heavily restrict abortion, the Alabama ruling felt like a nightmare. The state legislature’s efforts to make treatment available again have not allayed fears that a similar decision could cut off access in other states. That would take a physically and psychologically draining treatment that some have struggled to afford — cutting expenses, drawing money out of savings, or even changing jobs for the promise of fertility insurance — and make it unattainable.

Abortion opponents have had their eyes on IVF restrictions since well before the February 16 ruling from the Alabama state Supreme Court, which held that embryos should be legally protected as people — a long-term goal of the anti-abortion movement. That legal theory would make IVF nearly impossible to perform because of the issues raised by storing unused embryos.

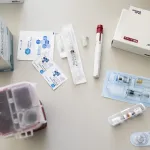

Doctors use hormones to boost egg production, then retrieve patients’ eggs. They fertilize promising ones in a lab. Not all fertilized eggs become viable embryos. Some aren’t able to keep growing, and others might have chromosomal abnormalities that mean they won’t result in a successful pregnancy. Once physicians determine how many embryos can be used, they can attempt a transfer into the patient’s uterus.

But because IVF is so unpredictable, invasive and expensive, physicians try to develop as many embryos as they can, freezing extras for patients to consider using later. When patients are done having children, they can choose to donate or discard those embryos. This practice has made IVF a political and legal target.

The Alabama ruling generated widespread disapproval. Recent polling found that two-thirds of Americans oppose the decision, and President Joe Biden criticized it in his State of the Union address, calling on Congress to pass federal IVF protections. Republican national lawmakers, while opposing that legislation, have sought to distance themselves from the court’s decision as well as from broader efforts to limit access to IVF. That’s true even though they largely favor abortion restrictions.

But other states could follow Alabama’s lead. So-called “fetal personhood” laws, which could be used to criminalize the procedure, remain on the books in 11 states, though only some extend legal protections to embryos outside the uterus. Iowa’s legislature has passed a fetal personhood law; it is currently waiting for the governor’s signature. State supreme court justices in South Carolina and Florida have expressed interest in enforcing such a law, with the Florida court’s chief justice suggesting the state constitution could also offer “rights to the unborn.“

The past few weeks have thrown into sharp relief just how tenuous access to IVF already was.

Patients like Dolan are considering out-of-state embryo storage options. Others said they are considering having a second child earlier, so that they can determine how many of their frozen embryos they will need to use while they still have the legal ability to dispose of any extras.

Taylor Edwards, 31, had been trying to get pregnant since the summer of 2020, but nothing worked. Finally, her doctor told her they were down to their last option: IVF. Edwards’ insurance would help pay some of their costs, but she estimates she and her husband would end up paying close to $40,000 out of pocket.

“All of our savings were just put back into IVF,” she said. “It felt like we were spending thousands of dollars every month just to keep trying.”

Edwards, who lives in Austin, Texas, underwent multiple embryo transfers, watching them fail one by one. The process was physically and mentally exhausting. And it’s something she thinks about now: If Texas law ever mirrored Alabama’s court ruling, would each of those lost embryos be considered a wrongful death? “Does that mean I‘m liable? Is my doctor liable?” she asked.

After the third transfer, Edwards finally became pregnant. And then, 17 weeks in, she received news she’d never thought to worry about: The fetus had a neural tube defect known as encephalocele. The doctor believed it would likely die in utero, or soon after. Edwards flew to Colorado for an abortion, a procedure outlawed in Texas. She grieved for her girl, whom she’d planned to name Phoebe. And then she resumed treatment.

She is now eight months pregnant, with three more embryos frozen. If all goes well, she’d love to give her child a sibling. But Edwards fears that by the time she is ready to give birth again, her options will be far more limited.

IVF is legal in Texas, and Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, has said he wants to keep it that way. But Edwards has her doubts. Texas was the first state to outlaw most abortions. Texas anti-abortion activists have indicated that in the long run, they want laws passed that address IVF-created embryos, too. And courts are unpredictable: A pending suit in the state court system would seek to apply Texas’ wrongful death statute to abortion, an argument with potential implications for IVF as well.

“I‘m scared that by the time I’m ready physically to through another cycle of IVF, that the laws will have shifted,” she said. “That’s a petrifying feeling.”

Already, patients go through extreme lengths to access IVF. That is unlikely to change, even without new bans on the procedure.

Keeley Johnson Crosby, a public health nurse in Wisconsin, started trying to become pregnant in 2021. After a year without success, Crosby and her husband tried intrauterine insemination, a cheaper, less invasive, but less effective treatment than IVF. Still, the time involved in the process — the regular injections, the countless, hours-long doctors appointments — felt like it took over her life. Crosby changed jobs, leaving her clinic-based nursing position to work in a health department, an office job with more flexibility to make all her new medical appointments. But the treatment didn’t work.

In 2023, they were ready to start IVF. But Crosby and her husband didn’t have the money. They couldn’t tell their families, let alone turn to them for financial help — their relatives didn’t support IVF.

Crosby’s husband changed jobs that spring, finding work at a company that explicitly offered IVF benefits. Crosby started treatment soon after. She became pregnant just in time – that August, her husband’s job dropped its fertility benefit.

Then last November, she miscarried.

“Even the idea of having one child that is carried to term and we get to take home feels so out of reach,” Crosby said.

They’re planning to start another round of IVF soon, using one of the five embryos they still have frozen. This time, Crosby and her husband will pay for the costs of the medications, along with that of transferring an embryo into her uterus. They’ve cut back on expenses wherever they can.

Crosby isn’t too worried about legal access changing any time soon. In Wisconsin, the status of legal abortion has fluctuated, based on how courts have viewed an 1849 law that criminalized the procedure and was never explicitly repealed. Currently, abortion is legal up to 22 weeks, though Republicans, who control the legislature, are pushing for a 14-week cutoff. The state Supreme Court has a liberal majority, thanks to the recent election of a justice who campaigned explicitly on protecting abortion rights.

Crosby takes that as a sign that — for now — IVF restrictions are too extreme for the state. And she has a backup plan, just in case: Crosby lives an hour from the Illinois border, a state with broad legal protections for reproductive rights. Her bigger concern is what will happen to other people.

“Even if something happened here, I’m OK,” she said. “I’m also acutely aware that anything that affects anybody’s bodily autonomy and right to make decisions for their family is really a threat to everyone.”