Your trusted source for contextualizing politics news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

An Alabama Supreme Court has effectively ended access in the state to IVF, leaving families navigating infertility in limbo.

The decision has sent shockwaves across the country. Democratic lawmakers have used the ruling to push for nationwide IVF protections, promoting a bill that Senate Republicans blocked on Wednesday afternoon. President Joe Biden has criticized the decision, and Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra traveled to Alabama this week to meet with affected patients.

Outside of Alabama, IVF patients have begun to question the security of their own treatment. Amanda Zurawski, the lead plaintiff in a case challenging Texas’ abortion bans, said this week she is moving her frozen embryos in case her state is next to curb access to IVF.

But the ruling’s implications outside of Alabama remain uncertain. Legal researchers have their eyes on a handful of states where similar changes could take effect, though it’s unclear when or how that might happen.

“It’s always difficult to predict what will happen in other states,” said Sonia Suter, a legal professor and bioethicist at George Washington University. “But there are other states that are very, very conservative that have strong evangelical leanings. You worry about it happening in those states.”

Now, the future of IVF access in other states boils down to how the treatment works, how state courts and legislatures decide to treat the rights of embryos, and the ever-evolving politics of restricting access to forms of reproductive health care.

Below, The 19th explains what that means in practice.

How does IVF work?

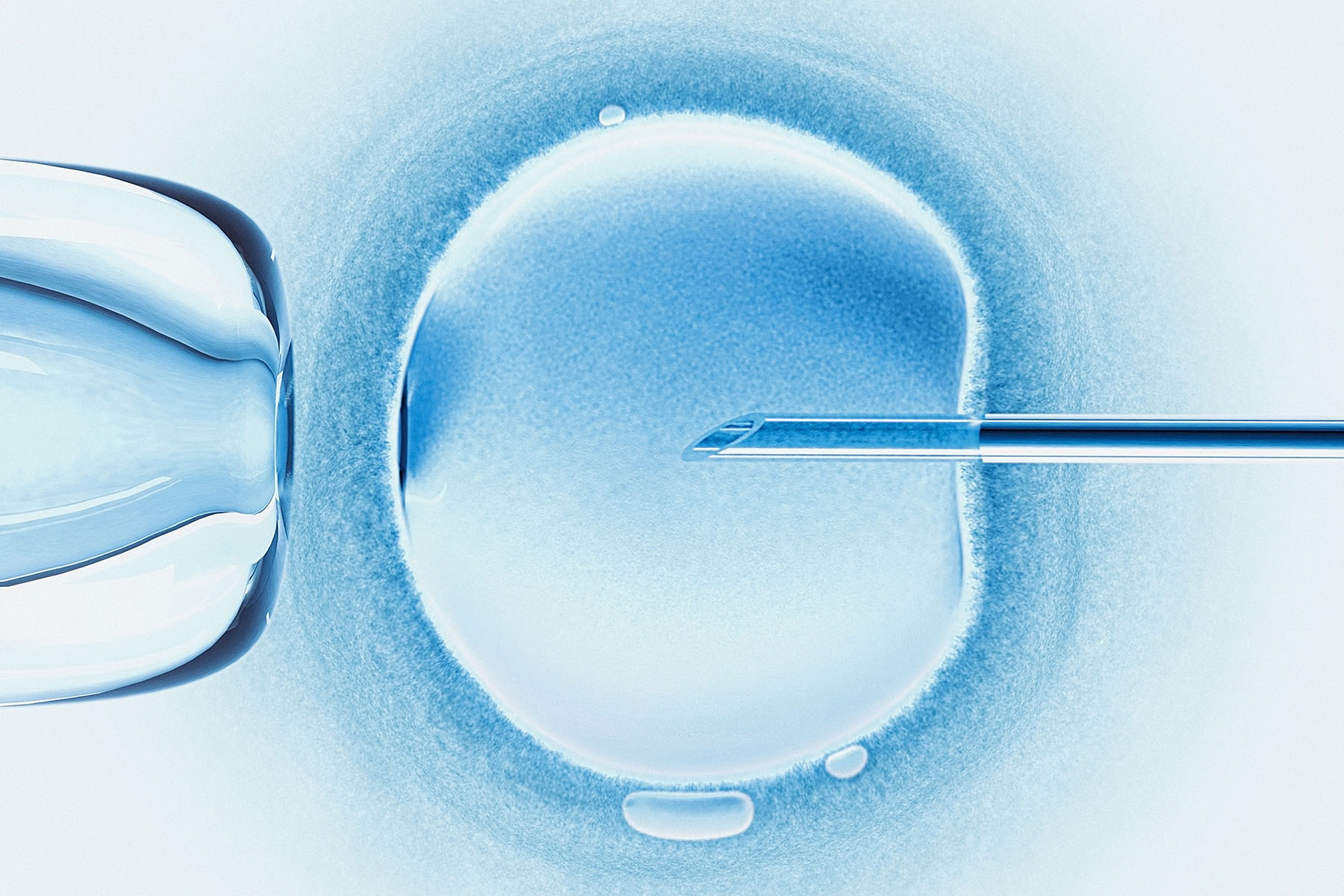

People receive hormones that allow doctors to retrieve their eggs, which are then fertilized with sperm in a lab setting. Some of those develop into embryos. Doctors screen those embryos to determine which are able to yield a viable pregnancy, and patients can then choose to have one implanted in their uterus. Excess embryos can be frozen for potential future pregnancies, can be donated to other families or for research, or can be discarded. IVF is considered the most effective option for people with infertility, and almost 100,000 babies a year are born through the process in the United States.

-

Previous Coverage:

-

Previous Coverage: ‘Gut punch after gut punch’: In Alabama, IVF patients speak out

Why has IVF become controversial?

Because not every cultivated embryo will keep growing, and not every embryo will be healthy enough to implant, doctors say that creating multiple embryos is critical to the process. But that component of IVF, and in particular the potential discarding of any embryos that are not implanted, has made the procedure a target for a contingent of the anti-abortion movement. With Roe v. Wade overturned and states moving to ban abortion, limits on IVF could emerge as a subsequent goal.

The Alabama decision stemmed from a question of whether unintentional loss of embryos stored at a fertility clinic constituted “wrongful death.” In a post on X, the Alliance Defending Freedom, a legal group that opposes abortion rights, called the Alabama ruling a “tremendous victory for life.” Students for Life, a prominent anti-abortion group, has long opposed IVF.

-

Previous Coverage:

What does this have to do with abortion?

Strident anti-abortion groups have argued in favor of banning IVF. They argue that life begins at the moment of fertilization, and that destroying or discarding embryos should be treated as a crime.

As a result, many abortion bans – by outlawing termination from that point, without specifying that the embryo must be in utero — could be interpreted to criminalize discarding embryos, making IVF impossible to provide.

After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, allowing states to enforce total abortion bans, some IVF patients scrambled to move their frozen embryos to jurisdictions that protected access to the procedure, just in case their states’ new anti-abortion laws might be interpreted to outlaw discarding embryos as well.

National anti-abortion bills — including the Republican-backed House bill known as the Life at Conception Act, which has 125 GOP sponsors — do not exempt IVF and could be used to outlaw the procedure. In some states, abortion bans specifically exempt IVF. But others — such as Texas, the largest state to ban abortion — are silent on the issue. For now, lawyers have broadly interpreted abortion prohibitions as unlikely to affect IVF. But some abortion opponents have made clear that limiting IVF remains a long-term policy.

Is banning IVF a new push within anti-abortion efforts?

Banning IVF is unpopular even among Republicans, who are more likely to favor abortion bans. GOP presidential frontrunner Donald Trump has sought to distance himself from the Alabama ruling, and the National Republican Senatorial Committee put out a memo last week instructing candidates not to back restrictions on the procedure. But the politics aren’t enough to push the GOP to embrace full-on protections; no Republican lawmakers have signed on to Democratic bills to secure access to IVF.

What could other states do?

There are a host of existing mechanisms that could be used to curb access to IVF.

Similar lawsuits to Alabama’s wrongful death case could be filed in other states. Louisiana already has a law that treats viable embryos as “judicial persons,” effectively meaning that embryos cannot be destroyed, though they can be transferred out of state. That law hasn’t stopped health care providers in the state from offering IVF, though it has made the process more cumbersome, physicians in the state said. They now have to send all excess embryos, including ones that will likely never be used for pregnancy, to out-of-state storage facilities.

Some legal scholars suggested that the Louisiana law could be leveraged in an argument for broader fetal personhood — the idea that a fetus, or even an embryo should be given the same legal rights as a person — and in turn reinterpreted to limit access to IVF. But so far, there are no pending cases in the state.

Laws granting legal protection to embryos — particularly so-called “fetal personhood” laws, which are on the books in 11 other states — could be interpreted to outlaw the discarding of embryos, making IVF, if not directly illegal, effectively impossible to provide. But those laws vary in their expansiveness, noted Mary Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis who studies the anti-abortion and fetal personhood movements.

Georgia’s fetal personhood law, for instance, only applies to embryos in the uterus and at six weeks of pregnancy and later, meaning it is unlikely to affect IVF. But an Arizona law, currently on hold while being litigated in federal court, applies personhood more broadly, including embryos. If upheld, multiple legal experts said, that is a law with the potential to undercut access to IVF.

More important, Ziegler said, is the makeup of individual courts and their willingness to embrace the same legal reasoning as Alabama’s. She pointed in particular to Florida and South Carolina, where members of the respective supreme courts have expressed interest in fetal personhood.

“You need a particular kind of group of people to make a ruling like this,” Ziegler said. “Definitely not just justices who are conservative but who are also interested in taking on this question at a time when doing so will be controversial and divisive.”

-

Previous Coverage:

-

Previous Coverage: Senate bill to protect IVF blocked by Republican objection

Should IVF patients in other states be worried?

People pursuing IVF, especially in states with leadership hostile to abortion, are navigating a new kind of uncertainty: whether it is safe to keep frozen embryos. Embryos that cannot be discarded must be used or stored indefinitely, a prospect that can be prohibitively expensive.

“People are wise to think carefully about the risks involved in keeping their embryos stored in abortion-restrictive states that either have personhood or are contemplating personhood,” said Katherine Kraschel, an assistant professor of law and health at Northeastern University. “Like so many other things involving reproduction it’s a very personal choice, and they should talk to their providers about benefits and risks.”

Andrea Edwards, a 38-year-old mother from Pennsylvania, called the uncertainty terrifying. Her son was born last July through IVF, and she and her husband still have two embryos frozen. They aren’t sure yet if they want another child, or if they would either discard those final embryos or donate them for medical research.

Edwards’ family doesn’t plan to relocate their embryos to another state. Though Trump has criticized the Alabama court’s decision, she said, she fears nationwide restrictions on the procedure if he is reelected, at which point she doesn’t know what options she would have – including whether she and her husband would have to quickly decide whether to pursue a second pregnancy or discard their final embryos quickly.

“I didn’t even know that this was something I would have to wrestle with before we started thinking about IVF,” she said. “It’s overwhelming and it’s scary and I just don’t understand how we got here.”

What’s happening in Alabama now?

Alabama’s attorney general has indicated he does not intend to prosecute medical providers or patients for using IVF. But the state Supreme Court’s decision has chilled access all the same.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham, the state’s largest provider of the IVF, has stopped offering the service. So have multiple fertility clinics in the state. Meanwhile, medical transport companies have stopped shipping embryos out of the state, fearing that they could be in violation of the ruling.

IVF patients in the state — including those who were about to have embryos transplanted — have had their treatment suspended indefinitely.

State legislators are scrambling to pass some kind of law that might protect IVF providers from civil or criminal liability, restoring access to the procedure. Republican lawmakers, who control the Alabama legislature, are on board. But both proposed bills are still in committee, and any timeline is unclear.