Editor’s note: This article has been updated throughout.

A Texas judge on Thursday said the Barbers Hill Independent School District can punish a Black student who wears his hair in long locs without violating Texas’ new CROWN Act, which is meant to prevent hairstyle discrimination in schools and workplaces.

The decision came after a monthslong dispute between the district and Darryl George, a junior at Barbers Hill High School who has been sent to in-school suspension since August for wearing his hair in long locs. Legislators last year passed a law called the Texas CROWN Act that prohibits discrimination on the basis of hair texture or protective styles associated with race. Protective styles include locs, braids and twists.

But the Barbers Hill school district successfully argued it can still enforce its policy that prohibits males from wearing hair that extends beyond eyebrows, earlobes or collars even if it’s gathered on top of the student’s head.

Judge Chap B. Cain III issued the ruling after a short trial in which lawyers for opposing sides argued over the legislative intent behind the CROWN Act. Lawyers for Barbers Hill said lawmakers would have included explicit language about hair length had they intended the law to cover it. Allie Booker, representing Darryl George and his mother Darresha George, said protective styles are only possible with long hair.

-

Previous Coverage:

“You need significant length to perform the style,” Booker said. “You can’t make braids with a crew cut. You can’t lock anything that isn’t long.”

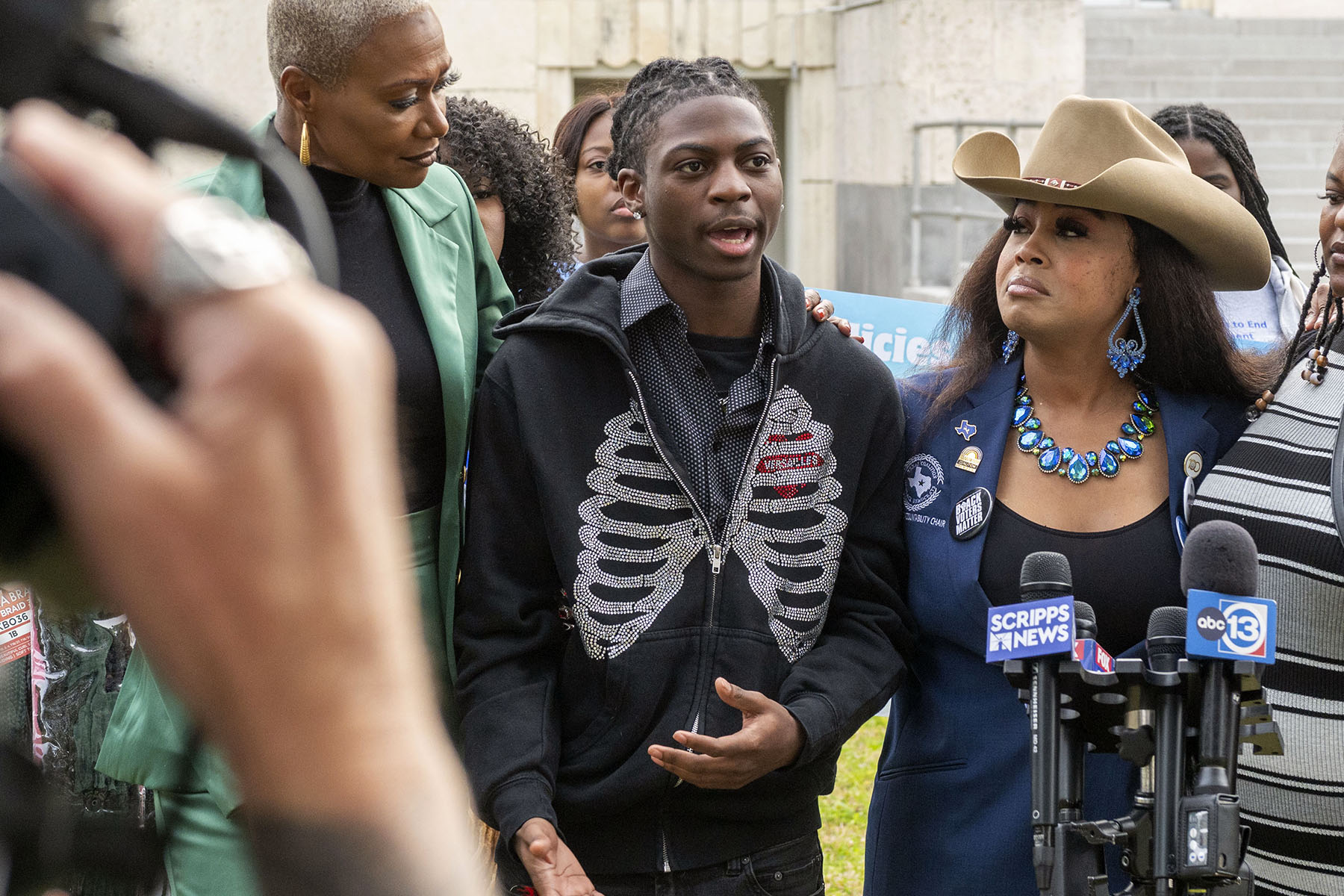

George exited the courtroom in tears, walking alongside his mother and several lawmakers who co-authored the CROWN Act.

“As I was walking down with Ms. George and Darryl, you could sense the anger, you could sense the confusion,” said Candice Matthews, the statewide chair of the Texas Coalition of Black Democrats. “Darryl told me, with tears in his eyes: ‘All this because of my hair?’”

Greg Poole, superintendent of the Barbers Hill school district, declined an interview after the decision came down. In a statement sent through the district’s spokesperson, Poole applauded the decision.

“The Texas legal system has validated our position that the district’s dress code does not violate the CROWN Act and that the CROWN Act does not give students unlimited self-expression,” Poole said.

Poole also suggested that a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on college admissions will have ramifications on Texas’ new CROWN Act.

“The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that affirmative action is a violation of the 14th Amendment, and we believe the same reasoning will eventually be applied to the CROWN Act,” Poole said.

Last summer, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned 40 years of legal precedent and rejected race-conscious admissions in higher education at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The majority found that the universities’ admissions policies, which use race as one of several factors in college admissions, violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause, which mandates that people are treated equally under the law. The majority of justices found that the race-based policies do not pass “strict scrutiny,” meaning the policies are not justified by a compelling state interest.

It’s unclear how the debate about the CROWN Act is analogous to that SCOTUS ruling. Unlike the college admissions case, Barbers Hill officials have not contested the legality of the CROWN Act itself. They have simply rejected a particular interpretation of the law. The Texas Tribune reached out to Poole to clarify his comments, but he did not immediately respond.

Booker said after the Texas ruling Thursday that she intends to appeal the decision. She also said she will file an injunction in a pending federal lawsuit filed by Darresha and Darryl George against the school district as well as state leaders.

During the trial, Booker called upon two witnesses: Darresha George and Rep. Ron Reynolds, D-Missouri City, who co-authored the CROWN Act and chairs the Texas Legislative Black Caucus. Attorneys asked George’s mother few questions, only asking her to identify her son and define his hairstyle.

Reynolds, however, was questioned at length as the two sides argued over the intent behind the law. Reynolds said he co-authored the bill because he was disturbed by Barbers Hill’s treatment of DeAndre Arnold, a Black student who was told he couldn’t attend his graduation ceremony at Barbers Hill High School unless he cut his locs. A judge issued a preliminary injunction in that case, blocking the school district from enforcing its policy in that particular case. Litigation is ongoing in the case.

“I felt compelled to file legislation to protect students who were similarly situated,” Reynolds said from the witness stand.

Attorneys for Barbers Hill repeatedly objected — with mixed success — to Booker’s line of questioning. They interrupted nearly every one of her questions to say they were irrelevant or that the intent behind the law was plain within the law itself.

“It would be an error to consider Rep. Reynolds’ comments as indicative of legislative intent,” Barbers Hill attorney Sara Leon said in her closing argument to the judge. “You do have evidence of legislative intent, which is the language of the statute, which does not mention length.”

Judge Cain ultimately sided with Barbers Hill, saying that the CROWN Act could have been written to say that individuals with braids, locs or twists are exempt from any hair length policy. He encouraged lawmakers to go back to the Legislature and file a new version of the CROWN Act that includes specific language about length.

The judge did not comment on the constitutionality of Barbers Hill’s policy, which Bookers had called into question during her opening and closing arguments. She said that the district’s grooming policy violates the equal protection clause of the Constitution because it is only applied to one gender. And she further argued that because the CROWN Act names a specific “protected class” of individuals with a particular hairstyle associated with race, the burden must be on the school district to prove that their grooming policy is the only way to achieve a “compelling state interest.”

“The district has not proven that the policy is tailored to serve those interests,” Booker said, citing an affidavit from Superintendent Poole that articulated the purpose of the dress code is to “teach grooming and hygiene, instill discipline, maintain a positive and safe learning environment, prevent disruption, avoid safety hazards, and teach respect for authority.”

In light of the ruling, George will remain assigned to in-school suspension, where he is allegedly denied instructional materials and hot food.

Before the trial, George said the experience has been isolating and damaging to his mental health.

“It feels lonely,” George said. “When you’re only stuck in one room for a whole semester it makes you feel some type of way. You see everyone else walking around talking and laughing and you can’t do that.”

This article originally appeared in texastribune.org.

Recommended for you

From the Collection