Gov. Jeff Landry will get his first opportunity to unwind Louisiana’s landmark criminal justice overhaul from 2017 this week when lawmakers meet for a special legislative session on crime policy.

Pushed by his Democratic predecessor, Gov. John Bel Edwards, the overhaul is a package of law changes designed to save Louisiana money by reducing its highest-in-the-country incarceration rate. It revolved around shortening criminal sentences and providing flexibility on parole.

Landry opposed those plans from the beginning, even after Republicans in the Louisiana Legislature embraced the changes. He doubled down on his position last year in campaign ads featuring crime victims and suggested harsher criminal penalties would give them relief.

“Enough is enough. We’re going to hold everyone — and I mean everyone — responsible for violent crime,” Landry said in a series of television spots.

But the 2017 law changes Landry has constantly criticized also poured millions of dollars into assistance for violent crime survivors who can struggle to get state support.

Over the past six years, Louisiana transferred $20.3 million from its prison system to much-needed crime victim services as a result of locking fewer people up, according to the Louisiana Legislative Auditor and financial records from the Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement.

The criminal justice overhaul reduced incarceration for nonviolent offenses, freeing up millions of dollars for programs that help survivors. Landry’s 2024-25 budget proposal retains the money ($3.6 million) for those services in the short term, but it’s not clear what will happen after next year.

Louisiana expects annual budget deficits of over half-billion dollars starting in 2025, when a large sales tax cut goes into effect. The governor is also pushing for harsher criminal penalties that would increase prison population and could put a strain on public safety resources.

State officials and survivors’ advocates said Landry’s administration hasn’t talked to them about whether scuttling the criminal justice overhaul will jeopardize funding for crime victim programs. The governor’s office did not respond to a request for this report.

“It is definitely for me a fear that we will be thrown out with the dirty dish water,” said Suzanne Hamilton, executive director of the Capital Area Family Justice Center, which relies on state money to provide services to domestic violence victims.

Resources for domestic violence victims

Louisiana’s criminal justice overhaul has been the largest and most reliable source of state funding for domestic violence victim services over the past decade. Since 2018, the state has used $6.8 million in financial savings from the prison population’s drop to pay for new programs for domestic violence survivors.

The Louisiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence received the bulk of that money, $4.4 million, to start a housing fund for people statewide trying to escape their abusive partners.

Clients at the state’s 16 domestic violence shelters can apply for financial assistance to help cover rent on a new home, utility bills, transportation to employment, a housing security deposit and child care. The money helps people transition from an emergency shelter to a permanent home of their own, instead of going back to a violent relationship.

“What is stopping people from getting free from violence is economic stability,” said Mariah Stidham Wineski, coalition executive director. “The ability to obtain a safe place to live that is your own and that is long term is essential.”

Wineski described the program as one of the coalition’s most successful, serving more than 1,200 people last year. Started in 2020, it relies solely on new state funding made available from the criminal justice overhaul.

The Capital Area Family Justice Center was also born out of the recent savings from cutting the prison population. With $2.2 million in state support since 2018, the center opened its doors in 2020 as a one-stop shop for counseling, legal services, childcare and other resources for victims of intimate partner violence. The organization has served 1,500 people so far, Hamilton said.

State officials deliberately targeted domestic violence survivors with the prison savings because Louisiana struggles with intimate partner violence. In 2020, Louisiana had the fifth highest female homicide rate of any state in the country, according to the Violence Policy Center. Of the 52 female victims that year, more than half were killed by an intimate partner, compared with just a third nationally.

For years, Louisiana governors and legislators didn’t put any state funding toward domestic violence victim programs, outside of a few hundred thousand dollars produced through marriage license fees. That changed in 2023, when lawmakers allocated an unexpected $7 million to domestic violence victim services statewide.

The support looks to be temporary. Landry’s administration did not include the allocation in his 2024-25 budget proposal like advocacy groups had hoped, Wineski said, making the money from the criminal justice overhaul all the more crucial.

Crime victims fund boost

Criminal justice savings also helped bring the state’s existing crime victims reparations fund out of a financial hole.

Since 2017, approximately $6.6 million from the overhaul has been deposited into the reparations fund, clearing a three-year backlog in victim payments, said Jim Craft, executive director of the Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement, which administers the program.

The reparations fund is a statewide resource providing financial relief to crime victims who have suffered hardship. People can apply to the commission for grants to help cover medical expenses, relocation costs, counseling, lost wages and rape kit costs associated with their attack.

Most victims receive compensation of $1,000 or less, but grants can reach $15,000. About half of the money distributed each year goes toward covering funeral expenses, according to the fund’s most recent financial report.

The crime victims reparations board struggled to give out grants for a few years because former Gov. Bobby Jindal had taken some of its money to fill budget holes in health care and higher education. That left the fund short on money to deal with crime victim requests until the prison population savings replenished its coffers.

“A lot of it we used to catch up on claims. We had to build it back up,” said Bob Wertz, the state official who manages the fund.

The fund is not in immediate danger of insolvency if it loses the prisons savings money, but advocates don’t want to see it diminished.

Katie Hunter-Lowrey, a crime survivor who works for the Promise of Justice Initiative, said Louisiana already spends far less per victim on reparations than Texas and Mississippi. She wants law enforcement and the state to promote the crime victims fund to more people.

“I think until the crime victims fund is serving every single person who needs it, not a dime should be taken away,” she said.

Clearing the rape kit backlog

The criminal justice overhaul also provided extra money for services for sexual assault victims.

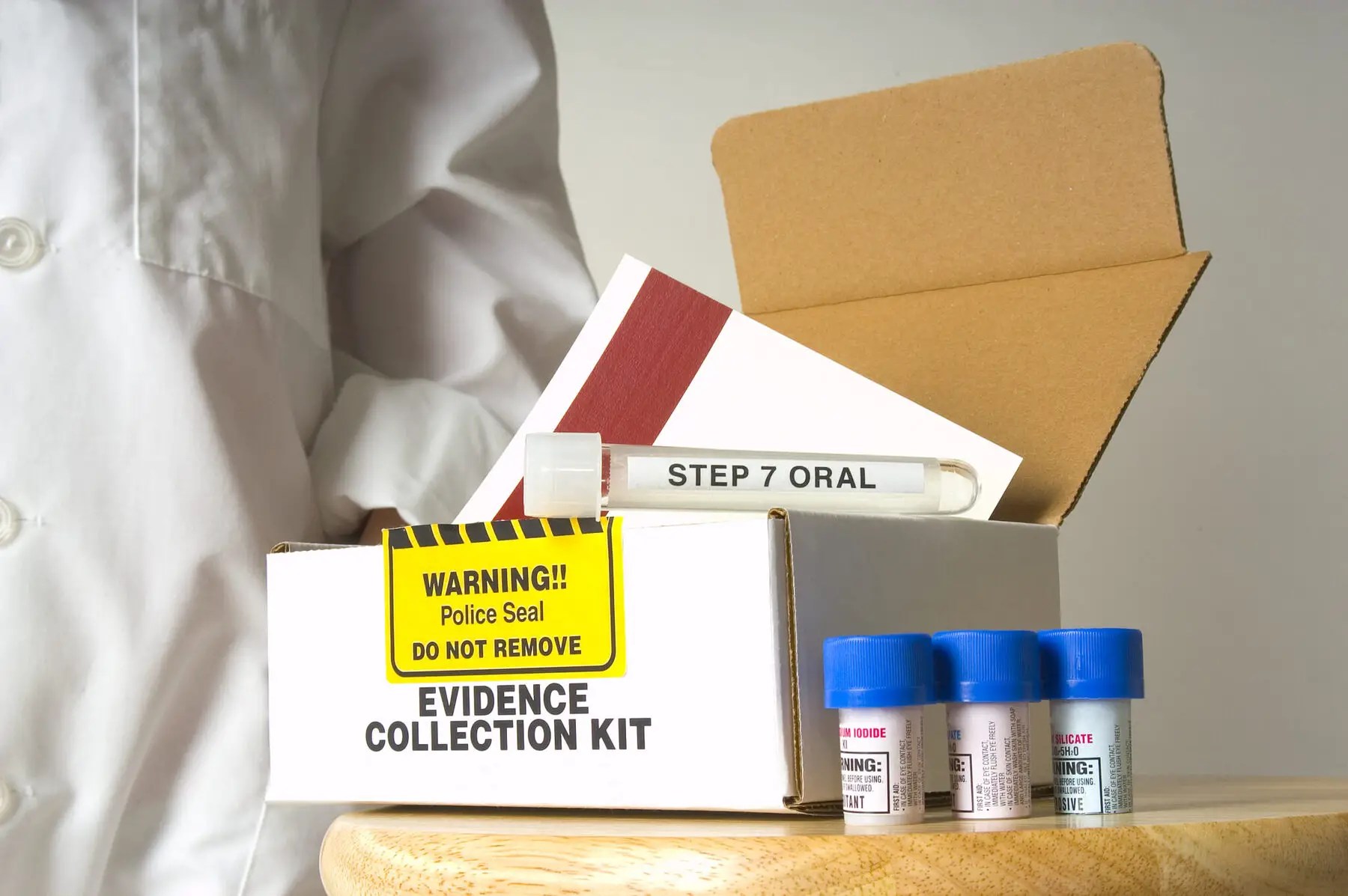

Crime labs in Acadiana, North Louisiana and at the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office have received $3.45 million since 2018, in part to clear the backlog of rape kits and property crime tests that hadn’t been performed. The St. Tammany Parish Coroner’s Office also received extra funding to cover overtime for nurses who perform sexual assault forensic exams on survivors.

“We continually face the challenge of accomplishing more with fewer financial resources each year,” Joseph Jones, systems director of the North Louisiana Crime Lab in Shreveport, wrote in an email. “The JRI funding has been instrumental in bridging this gap, enabling us to perform essential work and maintain our turnaround times across the laboratory system.”

Louisiana Illuminator is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Louisiana Illuminator maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Greg LaRose for questions: [email protected]. Follow Louisiana Illuminator on Facebook and Twitter.