Chloe Gayer didn’t think she was a survivor of domestic violence or of gun violence. She hadn’t been shot. She wasn’t married with children.

But when she was a freshman in high school, her boyfriend would constantly warn her that he had a gun in his pants pocket. “If you misbehave or if you upset me, I want you to know that I could shoot you and I could kill you right now,” he would say.

As she got involved with Students Demand Action, part of the Everytown for Gun Safety Network, she realized the label of survivor applied to her too. She had experienced the intersection between gun violence and intimate partner violence.

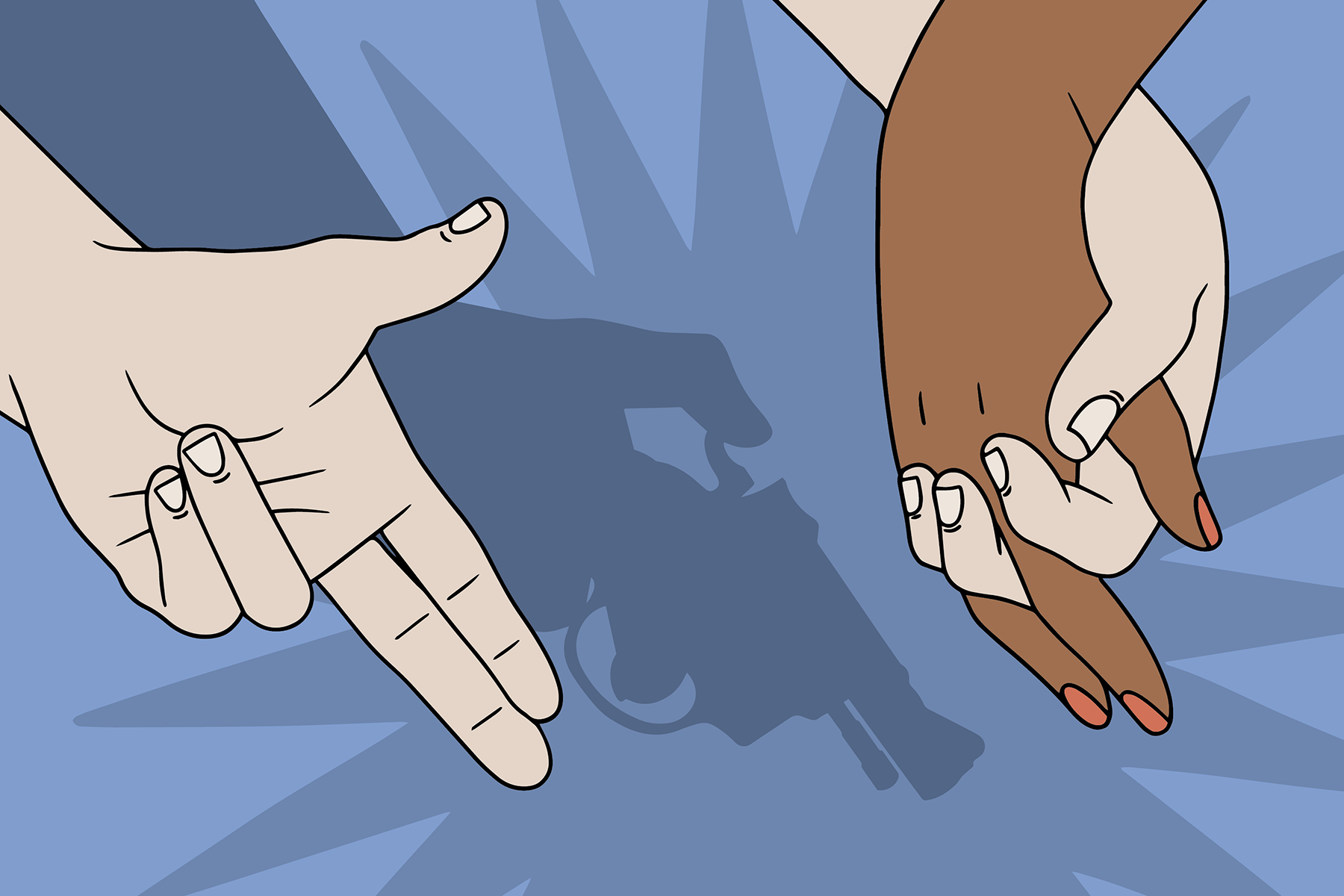

“I always thought anything that happens when you’re dating, it can’t have been that bad,” she said. But she learned how abusers used guns as a means of coercive control, often in ways less obvious than someone pulling a trigger.

When Gayer heard about the case being heard Tuesday before the Supreme Court, United States of America v. Rahimi, she was “just feeling so scared.” The case centers on the constitutionality of a federal law barring those with standing domestic violence restraining orders from possessing guns.

It felt too close to home, too familiar.

“I’m worried that the Supreme Court’s ruling could result in a very deadly decision.”

Attorneys for the United States are set to argue Tuesday that the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals was wrong in reversing its original ruling that Zackey Rahimi had violated a federal law that bars people from buying or possessing firearms if they have active domestic violence restraining orders against them. The 5th Circuit had originally found Rahimi guilty of violating this law, then reversed its opinion after the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2022 in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen.

In the majority opinion in Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that any restriction on firearms must be consistent with the “Nation’s historical tradition” — that is, have an equivalent example that can be found from the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification in 1791. This meant lower courts were suddenly tasked with reevaluating new challenges to long-standing laws on guns.

-

Read Next:

One such case was that of Rahimi, a Texas man who physically assaulted his girlfriend in a parking lot in 2019, then threatened to shoot her if she reported it. The woman got a domestic violence restraining order against him. Rahimi went on to threaten another woman with a gun and then was involved in multiple other shooting incidents. A police search found him to be in possession of multiple firearms and rounds of ammunition — thus putting him in violation of a 1994 federal law that bars the subject of a domestic violence restraining order from owning, possessing or purchasing a firearm

Rahimi’s attorneys are arguing that especially given the standards set by Bruen, that federal law is unconstitutional. They argue that it poses a total ban on firearms and ammunition to its subjects, carries a criminal penalty for violation, restricts gun rights over other forms of civic rights, relies on a civil and not criminal court order, and allows federal regulation to supersede states’ rights.

But gun safety advocates like Everytown for Gun Safety, medical groups like the American Medical Association (AMA), domestic violence support organizations like the D.C. Coalition Against Domestic Violence, and reproductive rights advocacy groups like the Center for Reproductive Rights have all filed amicus briefs with the court on the case, asking that the threat that firearms pose in domestic violence situations not be ignored.

“I would want people to remember one number, which is 500 percent,” Sabrina Talukder, the director of the women’s initiative at the progressive think tank the Center for American Progress, told The 19th. “Five hundred percent is the rate of increase of deaths when there’s a firearm in the home during a domestic violence incident. That’s just when a firearm is simply somewhere in the house.”

Recent data from the Pew Research Center showed that 40 percent of Americans, or approximately 199 million people, live in a home with a firearm. And according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline, 35 percent of all American women say they have experienced sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

Seventy women are fatally shot by a partner each month on average, Angela Ferrell-Zabala, the executive director of Moms Demand Action at Everytown for Gun Safety, told The 19th. “This is something that is not inevitable. This is totally avoidable,” she said.”If the Supreme Court hears these oral arguments and sides with the 5th Circuit, then what we’re going to see is basically a death sentence for women.”

And the implications of gun ownership on domestic violence do not end inside the home: Talukder also pointed out that between 2014 and 2019, two-thirds of all mass shootings occurred after the shooter had previously been involved in a domestic violence incident.

“Even when firearms are not used to kill, they’re used by abusers as tools to control, terrorize and threaten survivors, children and family members and this leaves physical, emotional and financial damage,” Talukder said. “We know that there are an estimated 433 million firearms currently in circulation [in America], which makes the United States a uniquely deadly place for victims of abuse.”

Mary Duplat describes her daughter Lorna Clark as outgoing, “interested in everything and everyone,” “an artist, actress, dancer and a punk.” In 1988, Clark was shot and killed by her ex-boyfriend in a murder-suicide the summer before she was set to start at California State University-Chico. She was 19 years old.

“She never got to attend a single class. She never got to have a family. She never got to reach for her dreams,” Duplat told The 19th. “Her life was senselessly cut short by a gun used by her ex-boyfriend.”

Clark had told numerous friends he planned to get a gun and kill Clark on his birthday. He wrote a letter and made an audio recording describing his outrage that Clark had dumped him and starting dating another friend of his.

“He ended up doing it the day after his birthday because their plans for that day changed,” Duplat said. “I didn’t have any idea he was planning to do this, but his friends knew. They knew, and they questioned him after he made threats, and then he convinced them all that he was just talking, that he would never actually hurt her. He would always say to her, ‘I’m going to kill you’ — to Lorna, in front of his friends, and they would all laugh.”

Duplat said she felt tremendous relief when the federal law at the center of Rahimi was passed in 1994. She thought about her daughter and about all the people whose stories would end differently because of this federal protection. “My daughter didn’t have any protections. There weren’t any laws then to protect her from this kind of domestic abuse. Thank God we have those laws on the books now, and for a reason — they save lives.”

Duplat said she is fearful about what the Supreme Court may do in ruling on the Rahimi case. “I feel like women are really getting the short end of the stick lately,” Duplat said, referencing the Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, which overturned the constitutional right to abortion previously set by Roe v. Wade. “I’m worried that now women are being dragged back in time, to a time when we didn’t have any protections and we were expected to be subservient to men. I’m not a civil rights expert, but I believe that there’s a full assault on women’s rights going on in this country.”

Diana Kasdan, the director of judicial strategy at the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), shares these concerns. CRR filed an amicus brief in the Rahimi case, calling attention to the ways in which the intersection of gun violence and domestic violence too often results in deadly outcomes for women.

But Kasdan is also concerned about what the use of the originalist philosophy outlined by Thomas in Bruen could mean for the future of civil rights, generally.

“If the court is evaluating where people are entitled to constitutional protection and that entails the government’s responsibility to secure those rights based on what laws were most like at the time of the founding — well, women were not considered part of the body politic then. Women were believed to be the property of or subject to their husbands,” Kasdan said.

It isn’t only women whose rights could be severely restricted by this kind of judicial interpretation, Kasdan said. It could also result in a “double down on this approach of circumscribing constitutional rights” that would most impact those “who have been historically excluded from political life, whether it be women, whether it be Black Americans, whether it be new immigrants.”

Ferrell-Zabala, the executive director of Moms Demand Action, underscored that though the organization she leads is focused on gun safety advocacy, its advocacy work on this case has led to a natural “pan out” to coalition building, bringing in experts who work in fields ranging from LGBTQ+ rights to children’s welfare to racial justice.

She describes the 5th Circuit ruling before the Supreme Court for evaluation on “an assault on women in this country, which is unacceptable.” Ferrell-Zabala said she is concerned about the documented post-Dobbs increase in calls to the National Domestic Violence Hotline about reproductive coercion. She also pointed to her experience at Planned Parenthood and the Planned Parenthood Action Fund, which informed her about how the case would apply to reproductive justice.

“Reproductive justice says that women and families should be able to live and raise their children, if they want children, in safe communities. That means we cannot have a guns everywhere agenda. Arming abusers is absolutely unacceptable. Homicide is the leading cause of death for pregnant women and postpartum women in this country,” she said. “If the Supreme Court does not make the right decision when it comes to Rahimi, this is a death sentence for women across the country.”

Today, Gayer describes the lingering effect of surviving gun violence in an intimate partner setting as the feeling a person might have after watching “a really scary movie.”

“The next night you might have nightmares or you might feel the creepy crawlies, but for the person that survived this, these creepy crawlies last your whole life,” she said. “The effects of being in an abusive relationship long outlives the relationship itself.”

It’s why she’s now majoring in political science at Drake University in Des Moines, with the hope of finding a way in her adult life to make communities safer from gun violence and domestic violence, especially rural ones like the one she grew up in in Iowa.

“I see hospitals closing, doctors moving away, resources just aren’t there in rural Iowa that we really need. I love my state. I love the people in it. If I’m going to do anything in my career, it’s going to be to support the people that raised me,” Gayer said. “Because of what happened to me, I spent a lot of time just trying to process it. That kind of grew into an isolation. I couldn’t focus on schoolwork. I just felt really alone. Even though I got out, I survived, I still have to work through that trauma — and by doing that I’ve been able to turn that pain into something.”

She wants more, not less, protections for domestic violence survivors. As someone who grew up in a military family and around firearms, Gayer said, she “respects the right to own a firearm,” but also feels so “tired of growing up in gun violence.” She wishes she could speak directly to the Supreme Court justices themselves about her lived experience.

“People with dangerous, abusive and violent histories shouldn’t be able to access a dangerous weapon,” she said. “This isn’t something that someone has to survive to know — that is common sense.”