Janeen Mendoza Cruz spent a decade working in the nonprofit and philanthropy world before she finally faced facts: Despite its promises, the space wasn’t truly willing to invest in people of color. Exhausted by the never-ending work of advocating for herself and her community, Cruz quit.

It was February 2020. As the pandemic spread and the world shut down, she sat on her couch and considered what was next. That’s when a friend asked the question that would change the course of her career.

I know you are taking some time off, but when and if you’re feeling up to it, can I get some salsa?

For years, Cruz and her husband, a Mexican immigrant, had been making salsa using his mother’s recipe. It was so popular among their friends and coworkers that Cruz sold some of it to her colleagues for a time in 2019. By early 2020, her friends were again asking for the couple’s salsa, leading Cruz to consider how she could turn a side hustle into a business.

“I just knew I needed to try something else,” she said. No tengo de otra. She had no other choice.

In the summer of 2020, she started selling jars from her home in the Bay Area to see if there was interest. Soon they were getting requests for shipments across the United States. In 2021, Cruz hired a business coach, and by 2022, her husband, Rodrigo Cruz Ayala, quit his job working for Mission Foods to join her, bringing his market expertise to the fledgling operation.

Now, they’re in 10 retailers in the Bay Area and shipping to 46 states under their brand, Kuali, an Indigenous Mexican word meaning good or quality. Their star product is a spicy salsa macha, a Mexican chili aioli that’s a mix of dry chiles, roasted pumpkin seeds and sesame seeds, garlic, cold-pressed grapeseed oil and a sea salt that is sourced directly from Colima, Mexico. They’re working on sourcing their chiles from Mexico, too. Kuali doesn’t carry a mild salsa, and they’re not planning to: “We’re not trying to appeal in any way to a White American palate,” Cruz said.

In many ways, the company Cruz built was her response to what she’d seen missing in the workforce as a daughter of Mexican immigrants who was seeking to do work that honored, not devalued, her people. As a person from a low-income immigrant background who grew up in the Woodville Labor Camp in California’s Central Valley, Cruz said Kuali was also her attempt at building her American Dream.

For her, only entrepreneurship held that promise.

“When you intimately talk to so many of us, we’re all leaving places that just weren’t enough for us,” Cruz said. “You see those numbers and you see that stat, and there’s just all the stories behind it as to why. It’s us being fed up with certain things but also being like, ‘OK, fine. We’re gonna make something work for us.’ That’s what we’re doing, and that’s what you’re seeing.”

The idea that owning a business can help build generational wealth and close wage gaps helped drive about 2 million Latinas into entrepreneurship in the United States. Before the pandemic, Latinas were creating businesses at a rate six times faster than all other groups, including White men and Latinos, and some data suggests that trend has continued.

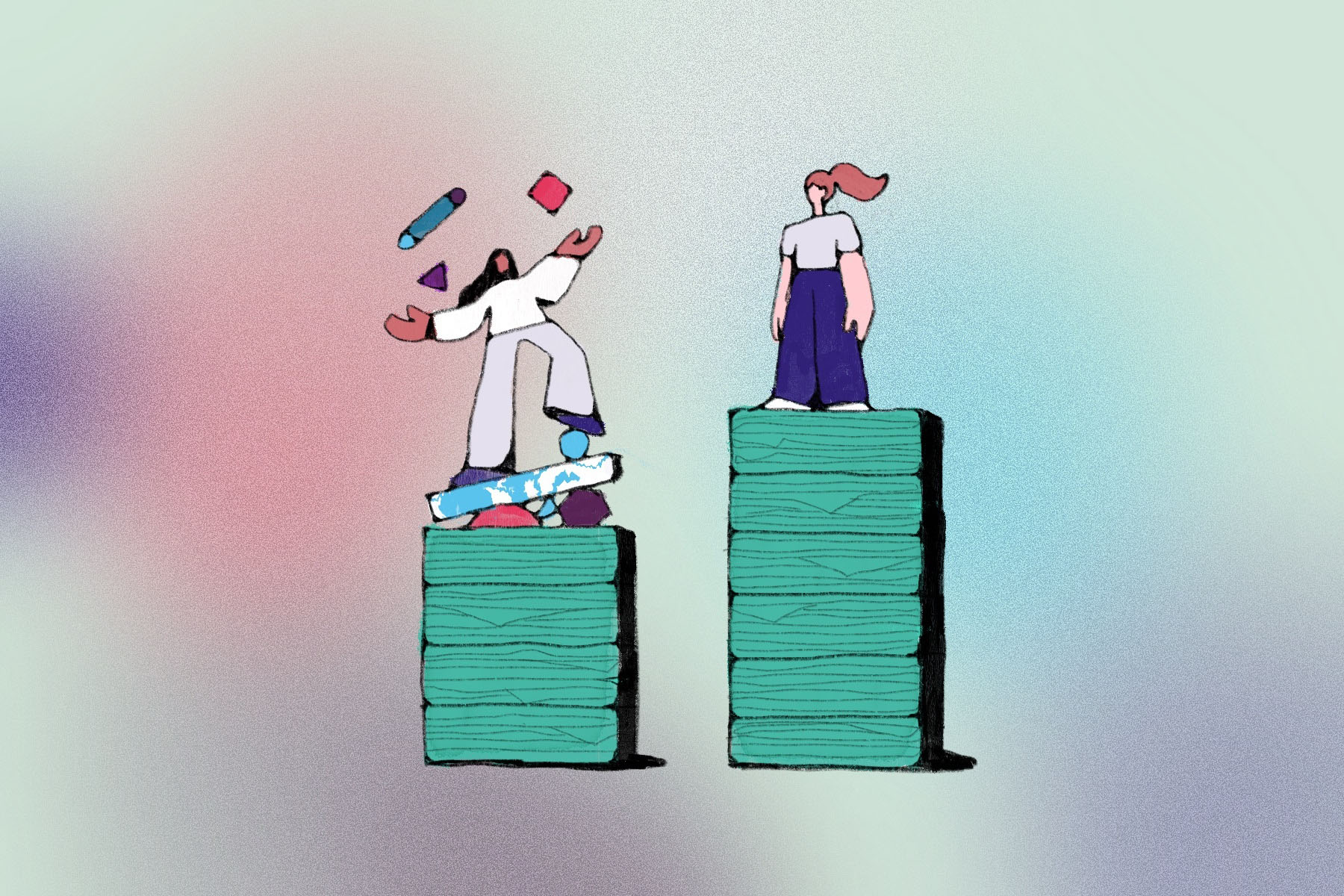

Currently, Latinas face the widest gender pay gap of any group, according to the most recent census data, earning just 52 cents for every $1 earned by White men. Latina Equal Pay Day, marked October 5, draws attention to that disparity.

Much of that gap is due to the overrepresentation of Latinas in the lowest paid and most volatile jobs in the country. About a third of the service sector is Latinas, the same field that faced the most job loss at the start of the pandemic. Latina unemployment hit 20.2 percent in April 2020 — the third-highest rate ever recorded in a single month and the highest ever by a group of women.

Latinas have recovered that job loss in an extraordinarily short period of time, and economists have attributed some of that recovery to entrepreneurship. Latinas are the most likely group to have young children and also older relatives under their care, leading them to seek more flexible work arrangements. Latinas are also among the most likely to face discrimination, microaggressions and barriers to advancement at work.

Business ownership has offered another path to that economic stability many Latinx immigrants come to the United States seeking. Still, it’s a hard road with its own with stubborn barriers, but if those barriers can come down for Latinas, experts said, it could help close racial wealth and wage gaps.

Isabella Casillas Guzman, the administrator of the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the highest ranking Latina in President Joe Biden’s cabinet, said there are about 20 percent more Latinx people opening businesses now than pre-pandemic, according to the White House. A substantial share are women. Latinas already own about 30 percent of Latinx businesses with employees. For comparison,White women own 16 percent of White businesses, according to an analysis of 2019 census data by the Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative.

“Entrepreneurship is a powerful pathway toward building wealth, strengthening communities and Latinas — and Latinos in general — are highly entrepreneurial and they have been for the past 10 years,” Guzman told The 19th. “It’s become the chosen pathway, I believe.”

Norma Muñoz started her embroidery business in 2020 as a way to earn extra income and continue to be present for her three daughters. She’d been exploring the idea for three years before she launched the business right before the start of the pandemic. At first, she joined the wave of mask sewers, standing four hours in line at JOANN Fabric and Crafts. But she’s been able to grow the business since by focusing on embroidery and screen printed T-shirts for other small businesses, many of them Latina-owned.

“The motivation for me is my family, because I always like to be here for them,” said Muñoz, who grew up in Mexico in a family of entrepreneurs. “When you start a business and you’re working for your goals, and that’s very good for your family, for your kids, seeing that.”

But building JKINnovations — the initials representing her daughters and husband — has come with sacrifice. When Muñoz was first learning to embroider, she had to scour the Internet for videos in Spanish and take Zoom classes during the pandemic on marketing and accounting. Even now, Muñoz still works full-time as a nanny — she cares for children from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., has dinner with her family, and finally works in her studio until about 9 p.m. fulfilling orders.

Historically, Latinas have had less access to every business-building resource, from banking relationships to the types of loans they get to even the kinds of federal contracts they have access to. The pay gap isn’t just in the workforce — entrepreneurs face it, too.

Latinx entrepreneurs are the least likely to use banking loans to start their businesses when compared with other groups — 12 percent compared with 17 percent of White businesses, according to a McKinsey & Company analysis of census data. And when they do get loans, they are less likely than White entrepreneurs to get the full amount they’re seeking, McKinsey found.

Latinas, who are at the intersection of both racial and gender disparities, feel that more acutely. One major barrier is that Latinx people have little access to government contracts, historically a source of stable income for small businesses. In California, for example, for every $1 businesses by White men made in government contracts in 2022, Latina-owned businesses earned only 10 to 34 cents, Stanford found.

Those challenges will only be made harder in the wake of the Supreme Court’s overturn of affirmative action, which has trickled down to affect an SBA program known as 8(a) that offers training and technical assistance to businesses run primarily by people of color. In early September, a federal judge blocked a provision in the program that allowed minority owners to qualify automatically as “socially disadvantaged” — now they’ll have to prove that disadvantage.

Since then, the SBA has been working to recertify the businesses in the program — about half already have been — and this week it reopened applications for new businesses. So far, no company has been removed as part of the court ruling, said Guzman, a former small business owner herself who has helped the SBA grow lending to Latina-owned businesses by 53 percent between 2022 and 2023. Still, she said the SBA will likely need “a couple years to break these really persistent, stubborn barriers.”

Those barriers played a role in the closure of about twice as many Latina-owned businesses in the first year of the pandemic as compared with Latino-owned businesses, according to Stanford’s analysis. The reason goes back to the issues with capital, said Barbara Gomez-Aguinaga, the associate director of the Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative.

“We found that Latinas had a lot less cash on hand to survive beyond six months compared to their Latino men counterparts,” Gomez-Aguinaga said.

Cruz, for example, recently had an opportunity to partner with Whole Foods but had to turn it down because she did not have the capital to launch with a big store, which usually requires fronting months of product to test out the brand and waiting even longer for payment.

“I can’t launch with a big store like that and be broke while I figure out if it’s going to work or not,” she said. She’s now working with a consultant to do some financial planning for the long-term so that Kuali is set up to take on Whole Foods-level opportunities when they come.

Entrepreneurship, she said, “is not for the faint of heart.”

Ana Flores, the founder and co-CEO of #WeAllGrowLatina, a network of about 26,000 Latina professionals, nearly all of them entrepreneurs, wants to ensure Latinas know how difficult the path to entrepreneurship is if they decide to take it.

“That over glamorization of entrepreneurship, the girlboss model, the hustle mentality — we are burning … the same corporate mentality into the ways we are creating businesses,” said Flores, who launched #WeAllGrowLatina more than a decade ago.

The reality is, Flores said, that many will struggle to build their businesses in an environment where Latinas are competing for a fraction of 1 percent of venture capital funds. If she was still in media, the industry she left to start #WeAllGrowLatina, she’d probably be earning more money, Flores said.

“I see entrepreneurship not only in the building of wealth, but for all the other opportunities it brings to the table,” she said. “My paycheck may not reflect what people might think it reflects for a company of my size, but the abundance I have received from this company and from being an entrepreneur, I would not change for anything else. I measure abundance and wealth in many different ways.”

Reaching for a way to build generational wealth, beyond just higher pay, was what also attracted Anyelis Cordero, a small business coach with a focus on Latinas, to entrepreneurship. She lived the pay gap in a real way when she was offered a director position in corporate human resources for $5,000 less than what she’d just offered to those in the program who had less experience than her.

She left instead to grow Propel on Purpose Coaching in 2021, which she’d started as a side gig in 2019. But by 2022, she was earning a third of what she was earning in the corporate world. It was around that time that she started considering focusing largely on Latinas, but she questioned it because of ideas the corporate world had instilled in her: If a Latina was advocating for another Latina, it was perceived as being because of their backgrounds and not their qualifications, something her White colleagues weren’t made to feel.

“If you’re the one referring somebody who looks like you, it’s sort of tainted with a preferential something,” Cordero said. “When it’s a White person who is hiring another White person, it never feels that way.”

Cordero decided she didn’t want to bring that mentality with her to her small business, and instead doubled down on her expertise as a Latina and Cuban immigrant.

“This is where I think the Hispanic experience is a value add … I can understand the cultural perspective and help them from a leadership perspective,” she said. “Like, ‘You’re quick to problem solve because we are taught to push through… but that doesn’t give you the opportunity to process all of the emotions relating to whatever you’re pushing through.’”

Speaking from her apartment in New Jersey with a view of the Statue of Liberty, Cordero said the idea of the American Dream has always been powerful for her community.

“We are here to make what might seem impossible possible,” she said. “My mom left an entire country, left her whole family, came here with no resources, didn’t know the language, didn’t know what to expect. Anyone who is an immigrant or the child of an immigrant feels the weight of that, but not in a bad way. It’s more like paying homage to them: How can I not honor that by living a bigger, bolder, more courageous life when she was able to do that?”

And that’s what entrepreneurship has been able to deliver for those who have seen success, like Alicia Villanueva, who came to the United States on a tourist visa in 2000 with her 8-year-old son and stayed. She settled in the Bay Area and worked cleaning houses and as a caregiver for the elderly and people with disabilities. Undocumented and with limited options, she turned to what she knew to help them survive: Every night after work she cooked from 10:30 p.m. to 3 a.m., then sold her tamales on the street along International Boulevard in Oakland.

Over time, she started taking classes in business planning and eventually launched Alicia’s Tamales Los Mayas in 2010 with the help of an incubator kitchen in San Francisco called La Cocina.

COVID-19 took a chunk out of the businesses, which by that point was 90 percent reliant on catering. They expanded past tamales. They knocked on every door. Among the biggest to answer: 10 school districts in California, Whole Foods, Williams-Sonoma and Alaska Airlines. Also in the works is a partnership with JetBlue, Delta and United Airlines.

Today, Villanueva employs 25 people, almost all of them Latinas who she often encourages to experiment at work and offer ideas to improve the business. Her three kids have all been involved in the business in some form and likely will be for years to come.

Villanueva’s American Dream was built on investing in her community, and that’s how she sees the future of Latina entrepreneurship, too.

“If we have this opportunity to come to this country, we have to leave a legacy of doing something positive, so they can see that we Latinos come here to help the country grow and to give to it,” Villanueva said. “I think we have to create opportunities for the community. That’s what I want — to have a positive impact, but in the name of all of us.”