Your trusted source for contextualizing LGBTQ+ and military news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Uruguay, Luxembourg, Brazil, Norway, Colombia, Malta and Chile are the countries that best uphold the human rights of their LGBTQ+ citizens, according to a report released last week.

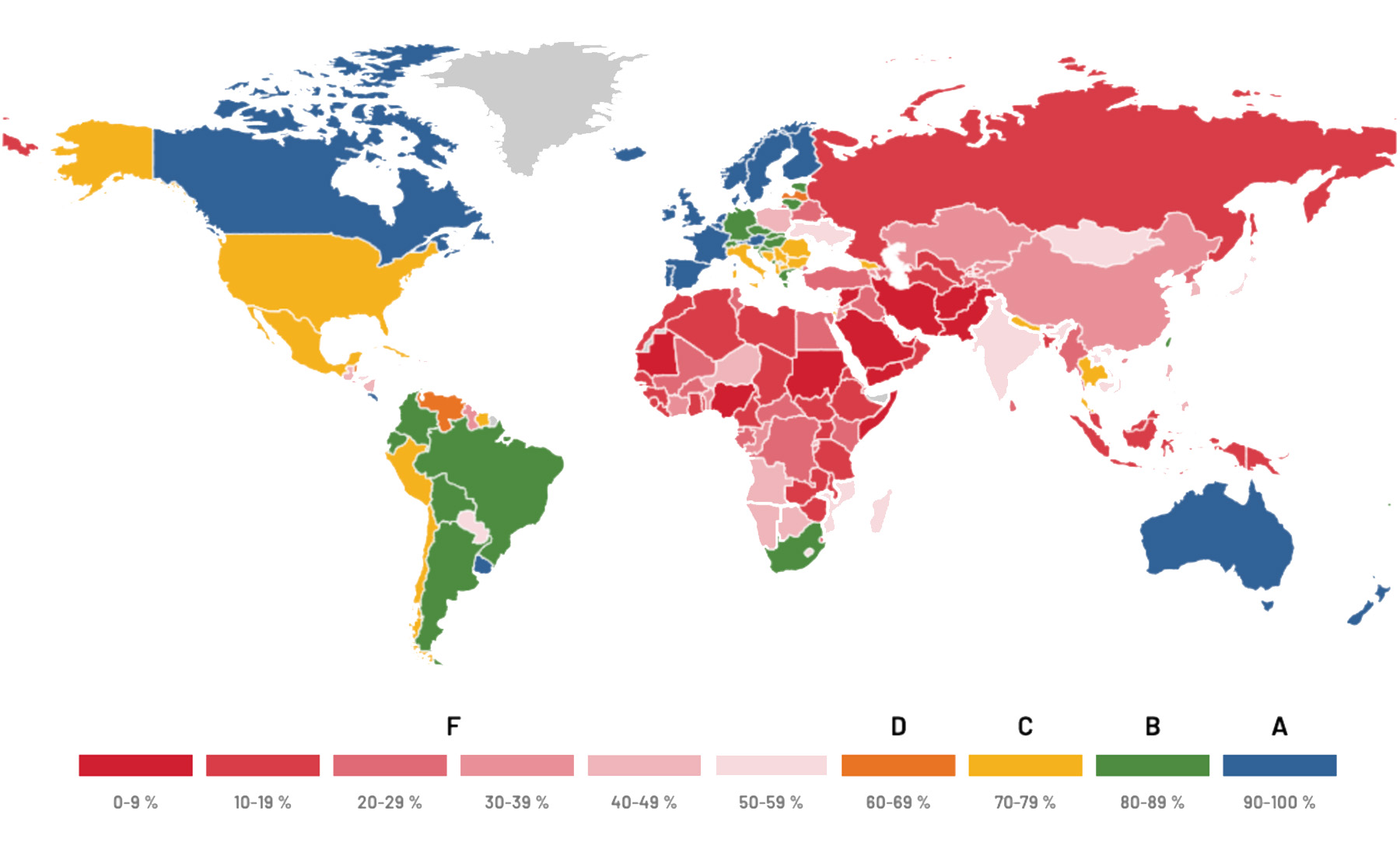

Conspicuously off that list? The United States, which scored a C or “resisting” grade when it comes to LGBTQ+ human rights on the Franklin & Marshall Global Barometers Report. The annual study, conducted by a partnership led by Franklin & Marshall College, delves into a country’s policies and as well as climate. It gave more than half of the world — 62 percent — an F.

The report ranked the United States 31 out of 136 countries, based on the lived realities of more than 167,000 queer people surveyed worldwide, trailing behind France, Vietnam and Hong Kong. But the United States is also headed toward a failing grade, said Susan Dicklitch-Nelson, professor of government at Franklin & Marshall College and the study’s founder.

“You’ll probably see a lot lower grades because if one state violates one of the items that we’re looking at, the whole country gets to zero, so there’ll be a downgrade for the United States,” Dicklitch-Nelson said.

This latest report looks at data from 2020. Since then, hundreds of anti-LGBTQ+ bills have flooded and passed state legislatures, most of them targeting transgender youth. In 2023, U.S. statehouses saw more than 700 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced, and lawmakers passed more than 70 of them.

Dicklitch-Nelson said Florida alone would lower the whole country’s human rights score because the state passed anti-trans legislation as well as the colloquially-known “Don’t Say Gay” bill that bans classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity. But perhaps more seriously, LGBTQ+ community groups can no longer safely gather in many parts of the country, she said.

“With the anti-drag laws that they have in Tennessee and in Florida, a lot of LGBT rights organizations are not able to peacefully or safely assemble, or pride events are not allowed by the state,” she said. “And do security forces provide protection [for] LGBT Pride participants? Again, that varies . . . depending on state.”

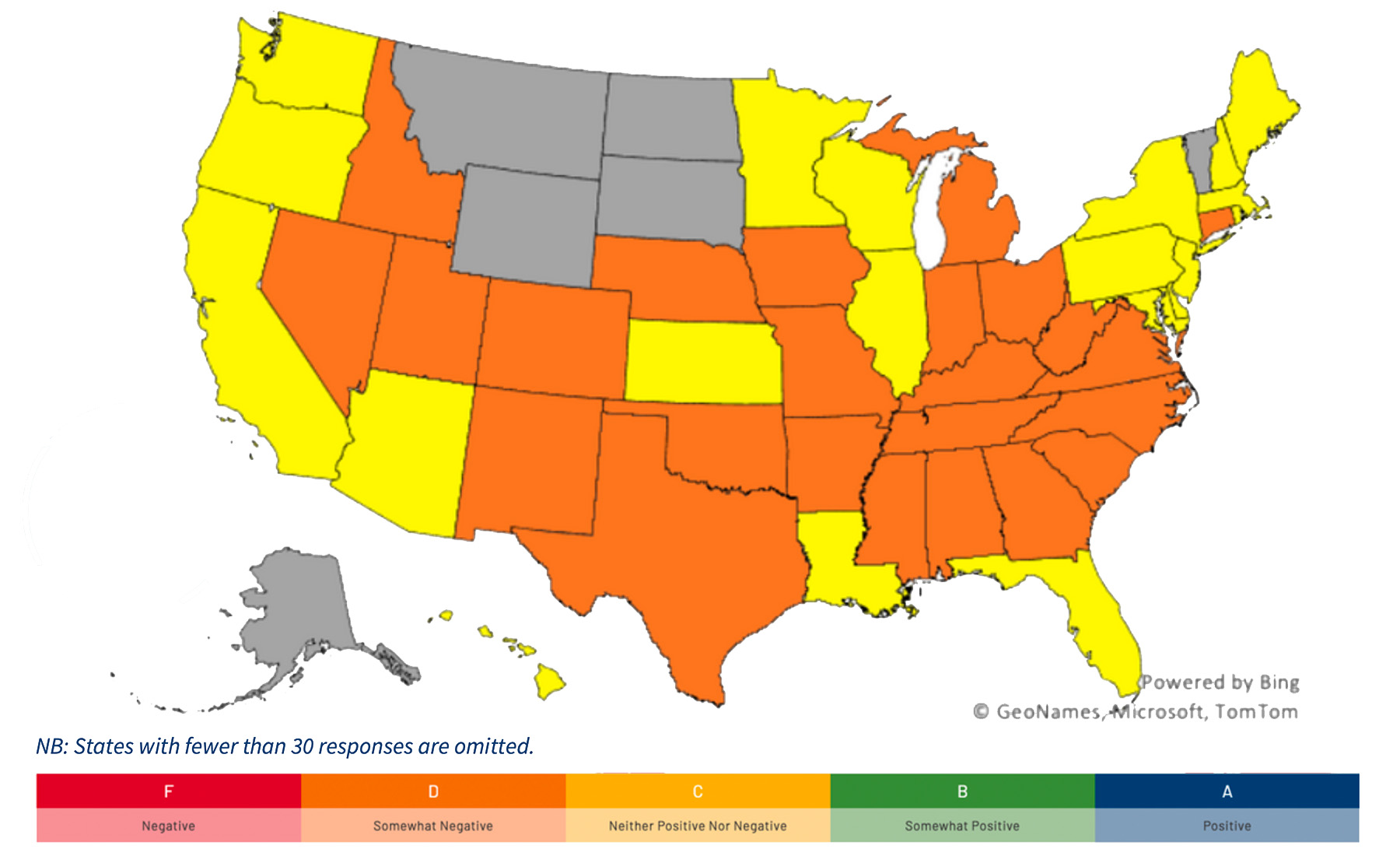

Breakout data from this year’s report shows that LGBTQ+ people throughout the country are fearful about the state of human rights in the United States. No individual state scored above a C grade, with nearly all getting a D rating.

That breakout data surveyed 13,809 LGBTQ+ people in the United States. Residents ranked Hawaii as the best state for queer people, followed closely by Maine and Massachusetts. Idaho had the lowest score.

The increasing push to criminalize transgender health care, ban books about queer people and bar drag threaten to place the United States in a grade category with Russia, much of the Middle East and most sub-Saharan African countries where LGBTQ+ people continue to face extreme persecution and violence.

The United States is hardly alone in its lackluster scores. The report examines countries over a 10-year span. As of 2020, only 42 percent of nations provided pathways to legal gender recognition, and eight percent criminalized gender identity expression altogether.

Still, much of the world has progressed over the past decade, said Dicklitch-Nelson. North Macedonia jumped by 53 percent from a failing grade to an A after the country passed anti-discrimination protections nationwide. The same protections have stalled in the U.S. Congress since 1974.

Dr. Anu Kumar, president and CEO of Ipas, an international nonprofit that advocates for reproductive rights, has studied the U.S. influence on global human rights. Earlier this year, the organization released a report that asserts U.S.-based organization Family Watch International helped fuel anti-gay policies in Uganda.

When U.S. organizations are exporting homophobia, she said, other countries face added obstacles in pursuing human rights policies.

“We in the United States hold ourselves up as the paragons of democracy, but clearly we are not,” Kumar said. “I think the point of those reports is not to compare Country A to Country B. The real lesson is to think about how we could all do better.”

Over the last 40 years, the world has made strides toward LGBTQ+ equality, research has found. However, that progress has been mixed with setbacks. The Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law found in 2021 that 56 of 175 countries advanced on LGBTQ+ equality since 1980. Still, 57 of them have regressed and 62 remained stagnant. That report found that the U.S. did improve in the last four decades.

The Global Barometers report noted that there appears to be a correlation between countries with the strongest records on LGBTQ+ rights also scoring well in protecting democracy and promoting economic growth. It remains less clear what that data means for countries scoring lower, however.

Kumar said her organization’s research shows that democracy is tied to human rights widely.

“We can’t really talk about these issues in silos,” Kumar said. “The anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQI movements are all part of the same broader attack on democracy. These things are connected.”

Regardless, Dicklitch-Nelson said the data raises interesting questions about the United States compared to other nations.

“It’s quite telling that a small country in South America called Uruguay has one of the highest scores,” she said. “Similarly, Malta, which is a predominantly Catholic country, has the highest grade.”