This Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

This Hispanic Heritage Month, we take a moment to luxuriate in reflection.

The Latinx experience in the United States is often one of constant movement, of pushing forward entire families and communities to ensure a future for the generations that come next. It’s an experience of hard work and sacrifice for many, and one that has often left little room for celebration of all we have accomplished. We are still learning our own histories and that of our community, which comprises more than 20 countries.

This month, we want to recognize the prosperity all of that movement has fostered, the power it has garnered and the progress it has created — especially for us, the generation that comes next.

The Latinx staff here at The 19th want to take this month to pause and highlight the family, community members and advocates who have contributed to our people’s prosperity in all of those big ways, but especially in the small ways. To the ones who have laid the groundwork, brick by brick, and shown us our power: gracias.

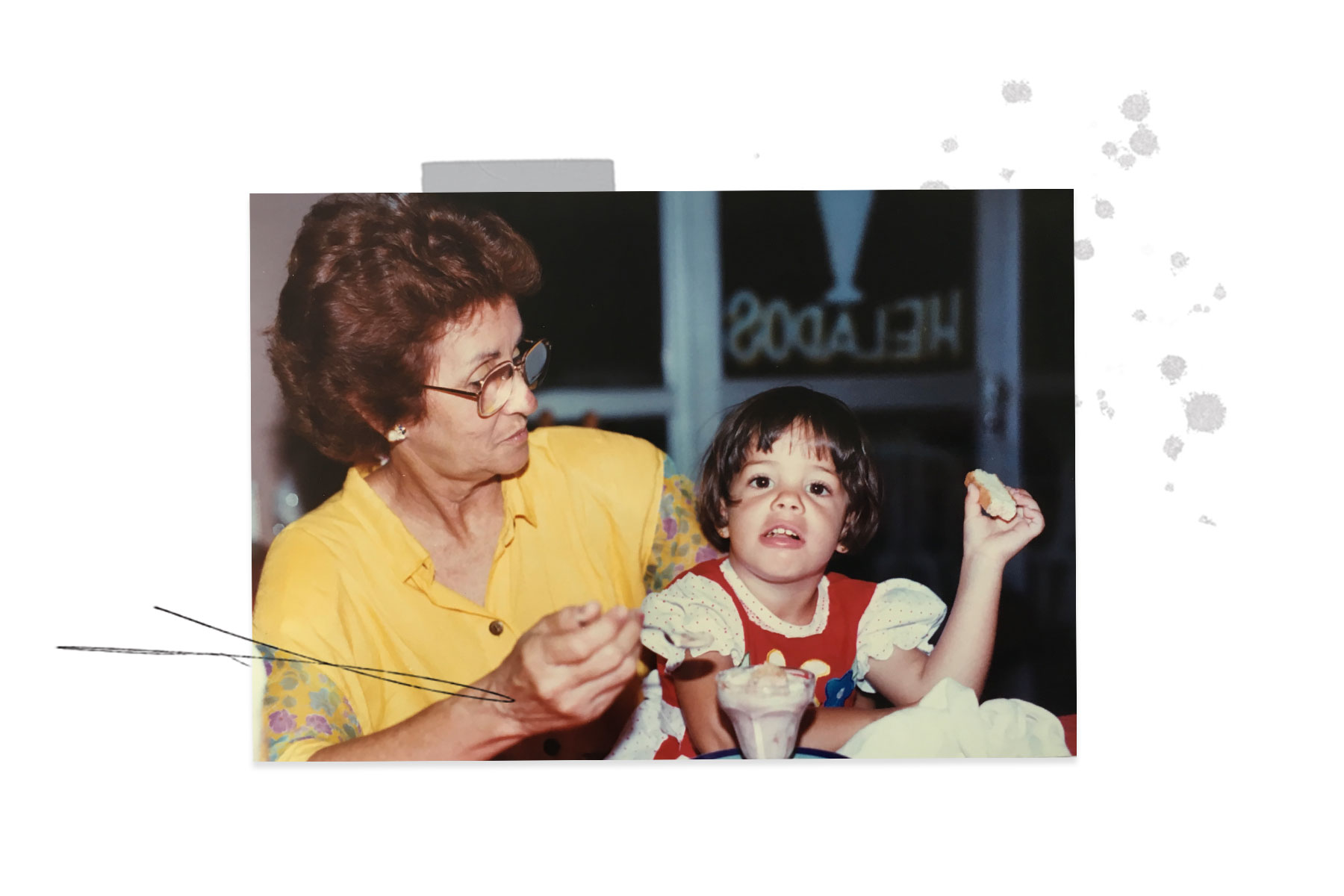

My daughter’s speech arrived like a gush — every day, a surprise new word. My husband and I sat down to take stock of them, trading stories about how each one had come about. Well into the 40s, I realized that very few were in Spanish.

When my family and I immigrated to the United States from the Dominican Republic in 2004, I was nearing 12 and understood very little English. My mom, who was learning English herself, would hand out M&Ms if we could name their colors. At school, I joined the other ESL kids for lessons in a mobile classroom that sat alone across the back parking lot. Like my daughter, my new words eventually gushed out, too.

Now, unless I’m surrounded by other people speaking in Spanish, my first language just lounges in my brain. The day after the big word count, I took on the task of recentering my Spanish at home with enthusiasm and some panic-induced erraticness. “Look, Maria, la lluvia!” “Here, tus zapatos!”

On FaceTime with my parents, a daily event around here, I start to worry that one day, she won’t be able to understand them. But when my mom says, Tírame un beso, my daughter blows back a kiss. When both of my parents say, ¿Dónde está María? she playfully covers her face. After we get off the phone, I ask if she wants a snack, and she responds, sí!

My mom, who helped me decipher my English homework and held me after rough days at school, is again indispensable, taking the lead in passing on our native tongue to her first granddaughter. This Hispanic Heritage Month, I’m thinking about how passing on my first loves — my country, my language — will always require effort and intention. And then I think about the ease with which my daughter loves her grandparents, and the quiet power of wanting to belong, which ties us all together. — Mel Leonor Barclay, reporter

My Spanish is a time capsule that I unlock at random times — when I’m frustrated with my puppies (no hagas eso!), or reminding my partner to pick up aguacates instead of avocados, or among Spanish speakers and feeling compelled to apologize for my limitations (lo siento, pero mi acento es mejor que me vocabulario). Though my parents spoke fluently at home, I didn’t really absorb the language until I was 4 and living with my mother in Mexico City. I vividly recall the sting of suddenly being rendered mute. But my body knew my mother’s tongue, and helped me find the words until I could speak and think in Spanish without trying.

My Spanish is a time capsule, reminding me that I am more than the shame of a stumbling tongue. I am my mother’s seventh child, perfect Spanish or not. For me, prosperity, power and progress is joining millions of other U.S.-born Latinos reclaiming our identities by reclaiming our language, our childhoods, our ancestors, poco a poco. — Amanda Zamora, co-founder and publisher

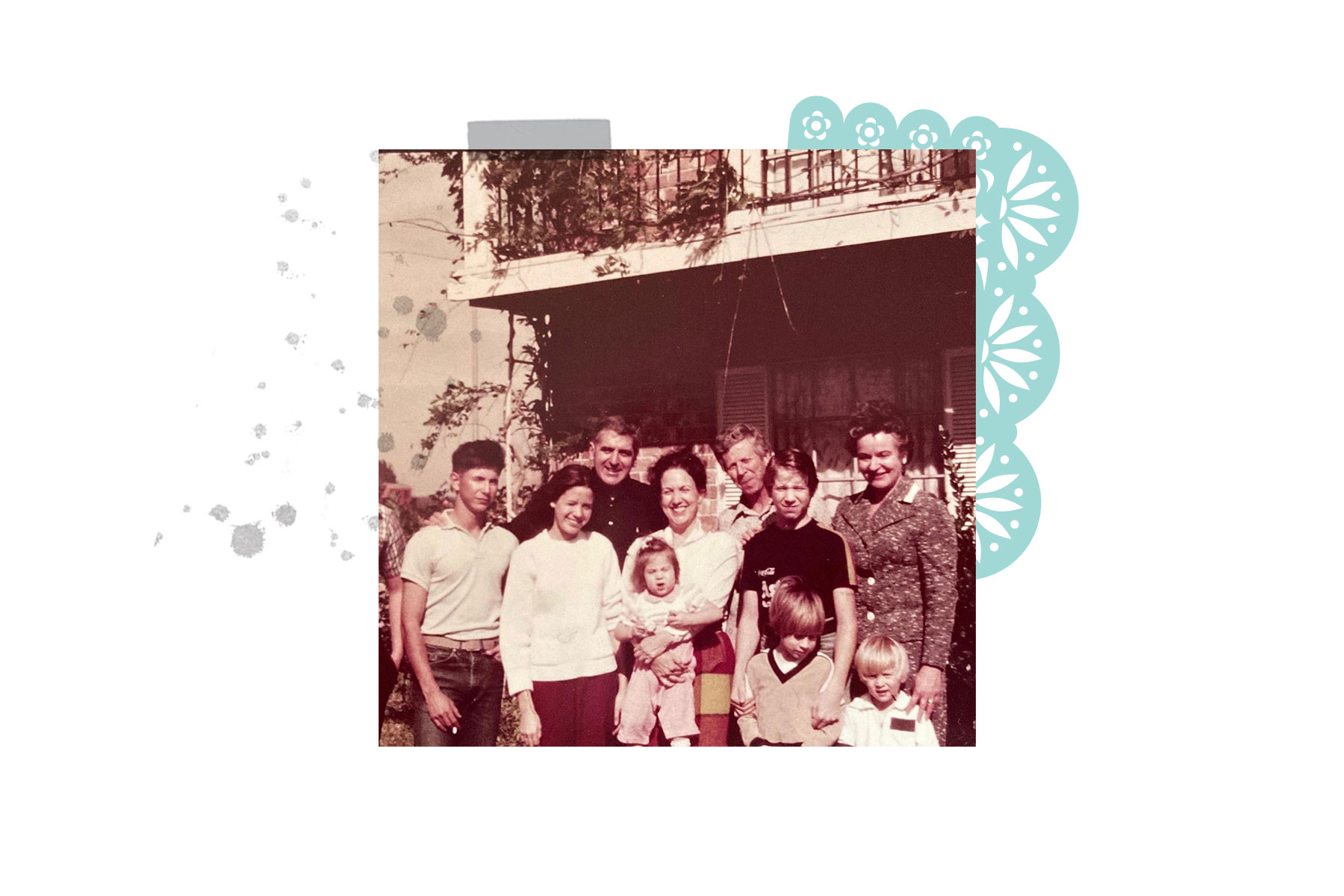

For most of my childhood, my Abuela Lila ran a small in-home daycare from our house, caring for babies as young as 2 months old and for elementary-aged kids after school. It was the kind of hustle that was emblematic of our culture: We were newly arrived Cubans in Miami doing whatever we needed to do to push our family to tomorrow.

I spent all of my school-age years watching her, already over 60, working so incredibly hard every day caring for kids, cleaning our home, cooking arroz con frijoles. She only stopped working at age 72, two years before she died in 2016. We lost count, but she must have cared for dozens of children.

It has taken all my life for me to understand that Abuela drove progress before we even recognized it as such. She helped all of those Latinx parents go to work and build toward their tomorrows. And she gave me a gift, helping me see that all the work that is cast aside as less-than, the work our communities are most likely to do, is perhaps the most important work of all. Now, I write about child care in her honor. — Chabeli Carrazana, reporter

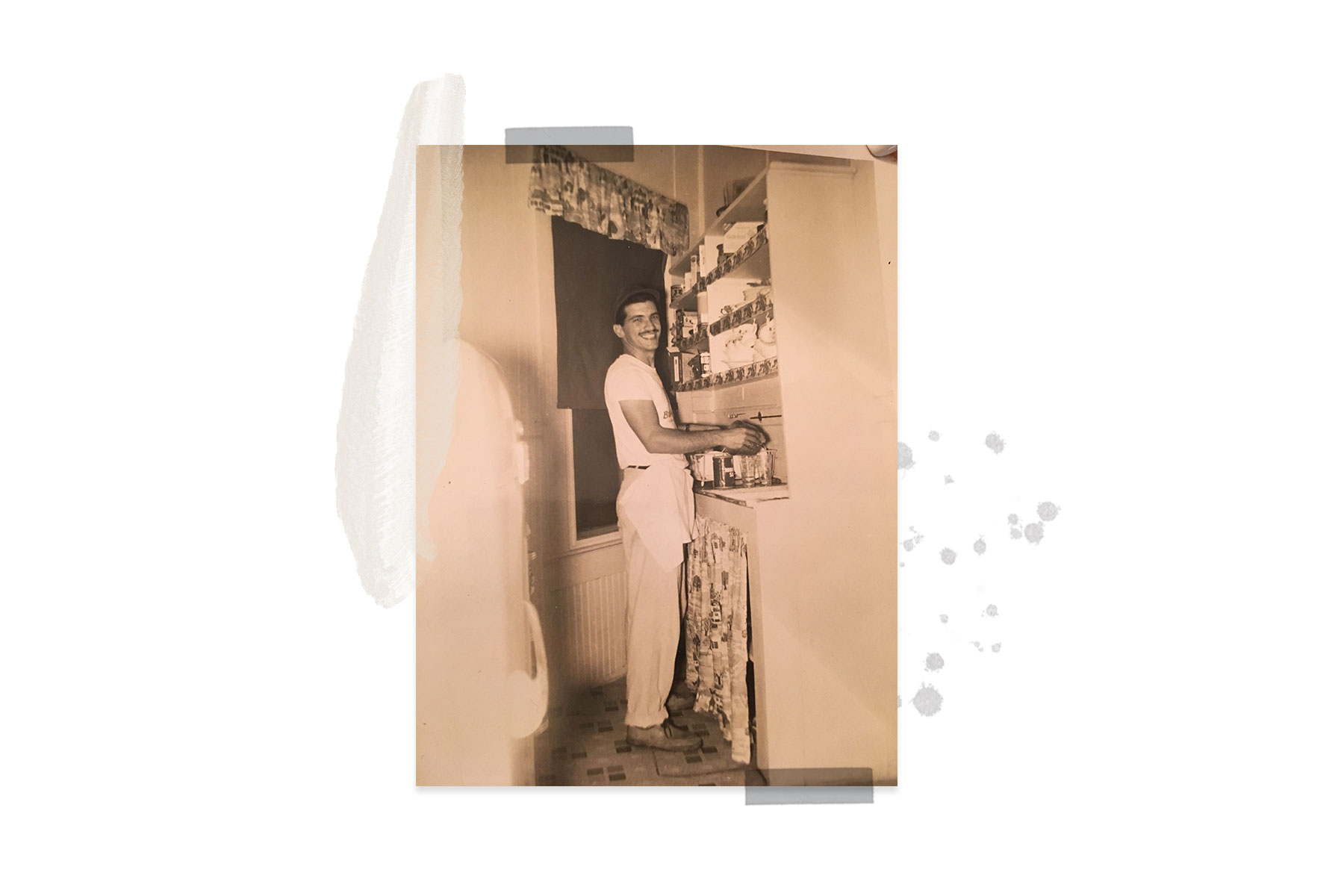

I came across an old newspaper article this summer at my grandparents’ house, highlighting the radio show my Pop started after moving to Key West from Cuba, “Música y Alegría.”

“I love this town, but how come there are so many Spanish-speaking people and no Spanish radio?” he said in the article’s interview.

I was captivated by the story, mostly because it was a quintessential Pop move. No radio show to serve his community? He started his own. I’m still wondering where he possibly learned radio skills before endeavoring on this project.

But that’s just who he was — a true “American dream” chaser who was a force, a barrier-breaker and a pillar to all who knew him. He instilled the same desire for representation and progress in his children and grandchildren, and I think often about how his thoughtfulness and can-do attitude shaped the core values he passed on to us. — Megan Kearney, digital producer

As an immigrant the ground beneath your feet always feels unstable. You build the foundation of your new life on a culture left behind and the hopes for a better future.

My family came to New York City in the ’90s during a particularly difficult time in Colombia’s history. While my family always centered our culture and language in our daily lives, the feeling of being ni de aqui ni de alla persisted.

I grew up in one of the most diverse communities in the country and had the privilege of being surrounded by other people who spoke and looked like me.

It wasn’t until after college, after I left New York and the structure of school that I felt lost for the first time about who I was and my place in the world.

So I did what any 20-something with little responsibility would do: I left my consulting job and moved to Colombia with no plan.

I arrived speaking fluent Spanish but with a heavy tinge of American-ness in my accent. I couldn’t name all of Colombia’s states or even where major cities were. I spent the next two years working at startups, traveling to more states than I ever would have imagined, and making incredible friends.

I returned to New York with a deeper sense of where I came from. For the first time, I felt settled and content in my decisions about where I lived and who I was. My foundation was now built of stronger stuff. — Andrea Atehortua, product operations manager

I think sometimes for people who are mixed race or multiethnic, heritage months can be a confusing part of the year. They celebrate one part of your identity, but you also know you aren’t neatly split into halves like a cut piece of fruit. All the parts of you merge and mesh and influence how you are seen in the world — and how you see yourself.

My mother is from Bogotá, Colombia, and my father is from Springfield, Missouri, and for me, Hispanic Heritage Month is about celebrating that complexity that exists within myself and the Latinx community and the ways it molds and shapes us. It’s deeply personal.

This month I’m honoring my ancestry and reflecting on how my life, and that of my friends and family, contribute to this unique mosaic of culture and identity. — Jessica Kutz, reporter

Education was not necessary in the rural Mexican town where my mom, Isabel Valdez, was born and raised. Going to school was commonly seen as second to household chores. So, when my mom finished primaria (elementary school), she did not return to school, despite her interests.

Instead, at just 11 years old, she became a full-time caregiver for her recently widowed mother and nine siblings. Alongside her older sister, she washed clothes, cooked meals for the family and kept their house tidy.

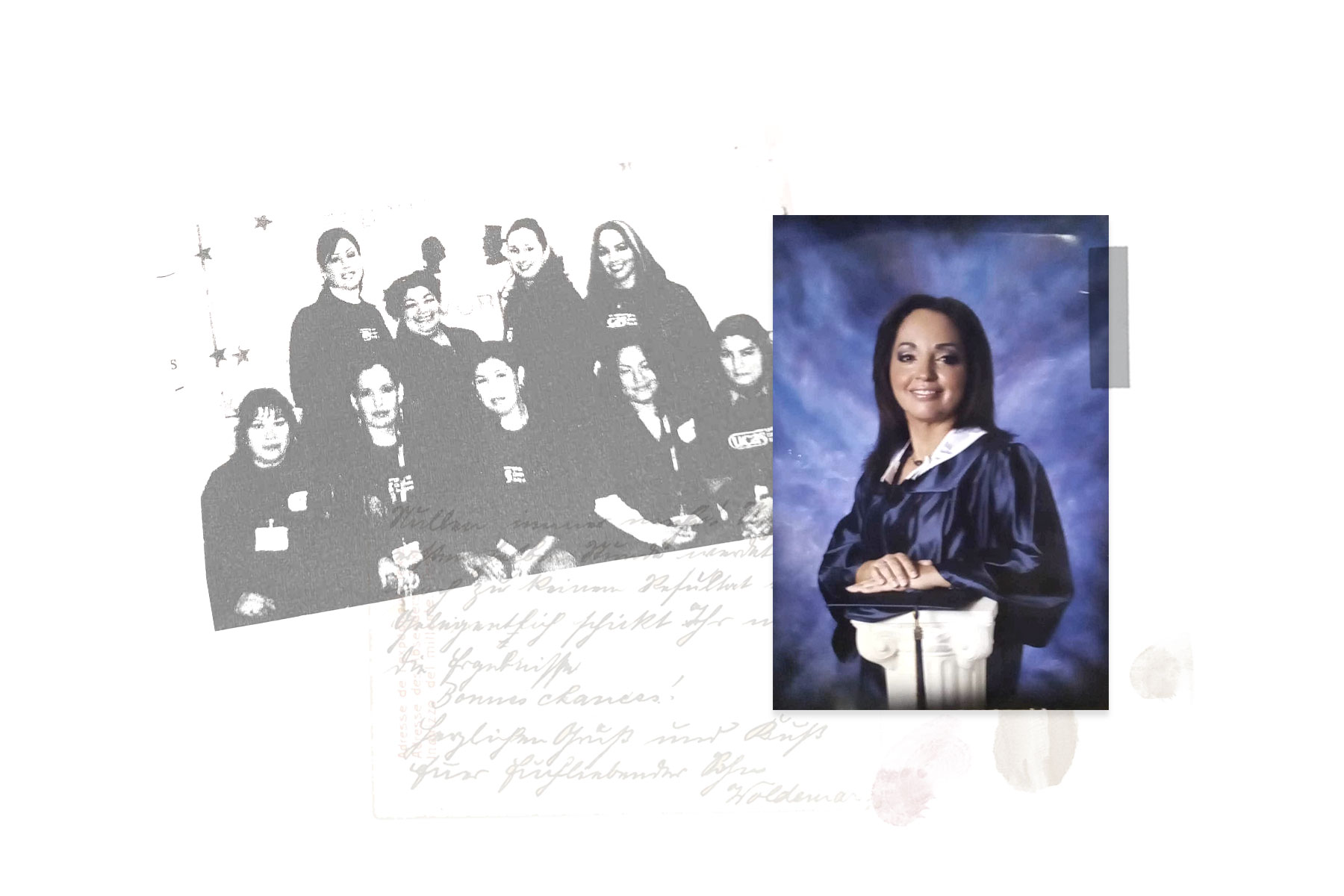

Twenty-nine years later, newly divorced and a single mother to four kids, she returned to school. Through a variety of side hustles, including selling homemade tamales and Cotija cheese, she was able to pay for cosmetology school. At 42, she earned her license and began working at a nail shop. When I started middle school at 11, she opened her own nail shop. My mom’s hard work and perseverance to continue her education have led my siblings and me to a place in life where we are able to build on her prosperity. — Myrka Moreno, audience engagement producer