Your trusted source for contextualizing education and health news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

The type of sex ed students in this country receive depends largely on the state they call home. Some youth learn about the importance of consent or contraception, while others receive instruction on abstinence or sexually transmitted infections. Some don’t get any sex ed at all.

What nearly all students in the nation have in common, however, is that they live in states that don’t require them to be taught comprehensive sexuality education.

Characterized by experts as the gold standard of sex ed, comprehensive lessons are medically accurate, LGBTQ+ inclusive and age appropriate. They address sexual behavior and sexual health, human development and healthy relationships, and research has found that students who receive comprehensive sex ed delay the onset of sexual activity.

Just three states — California, Oregon and Washington — require comprehensive sex ed to be taught in all schools, according to the Sexual Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). That’s a reality that new legislation introduced by Rep. Barbara Lee seeks to change.

By creating federal funding for high quality sex ed, the Real Education and Access for Healthy Youth Act (REAHYA) encourages states nationwide to provide students with evidence-based instruction and sexual health services that are comprehensive, equitable, medically accurate, culturally responsive, trauma-informed and resilience-oriented, among other criteria. In addition to learning about the prevention of STIs and pregnancy, students would learn about interpersonal violence, autonomy in health care and gender identity. Particular attention would be given to addressing how marginalized youth haven’t historically received equitable access to sex ed or sexual health services.

“Education is power, and young people have the right to make decisions over their own bodies,” Lee, a California Democrat, told The 19th via email. “Abstinence-only sexual education programs and the lack of evidence-based sexual education for America’s youth leaves them vulnerable to health risks and disparities. The REAHYA Act would close these disparities in sexual education by giving all students access to the personalized information they need to be safe.”

Many of the states that limit what students learn about gender and sexuality also restrict access to reproductive rights, making comprehensive sex ed “exponentially more important,” Lee said.

“Those on the far-right want to attack people’s ability to make their own decisions over their bodies, while also depriving people of the information necessary to remain well-informed,” she said. “They need to keep all of their bans off our bodies and our books.”

The legislation has been referred to the Subcommittee on Health and includes 38 cosponsors, including Reps. Alma Adams and Pramila Jayapal as well as Sens. Mazie Hirono and Cory Booker, all Democrats.

REAHYA would provide $100 million in funding from 2024 to 2029 for both K-12 schools and higher education institutions to teach comprehensive sex ed, with a particular focus on serving marginalized young people that have often been unable to obtain quality instruction.

Two years ago, Lee unsuccessfully introduced REAHYA legislation. During an age of parents’ rights bills, censorship laws and other legislation that limits what students can learn, what gives her hope about the bill’s prospects in Congress this time around?

“Republicans may have the majority, but we have the momentum and the people on our side,” Lee said. “I am hopeful that our coalition for reproductive rights and comprehensive health care, including sexual education, will take back the power in Congress and enshrine our rights to make decisions over our own bodies into law.”

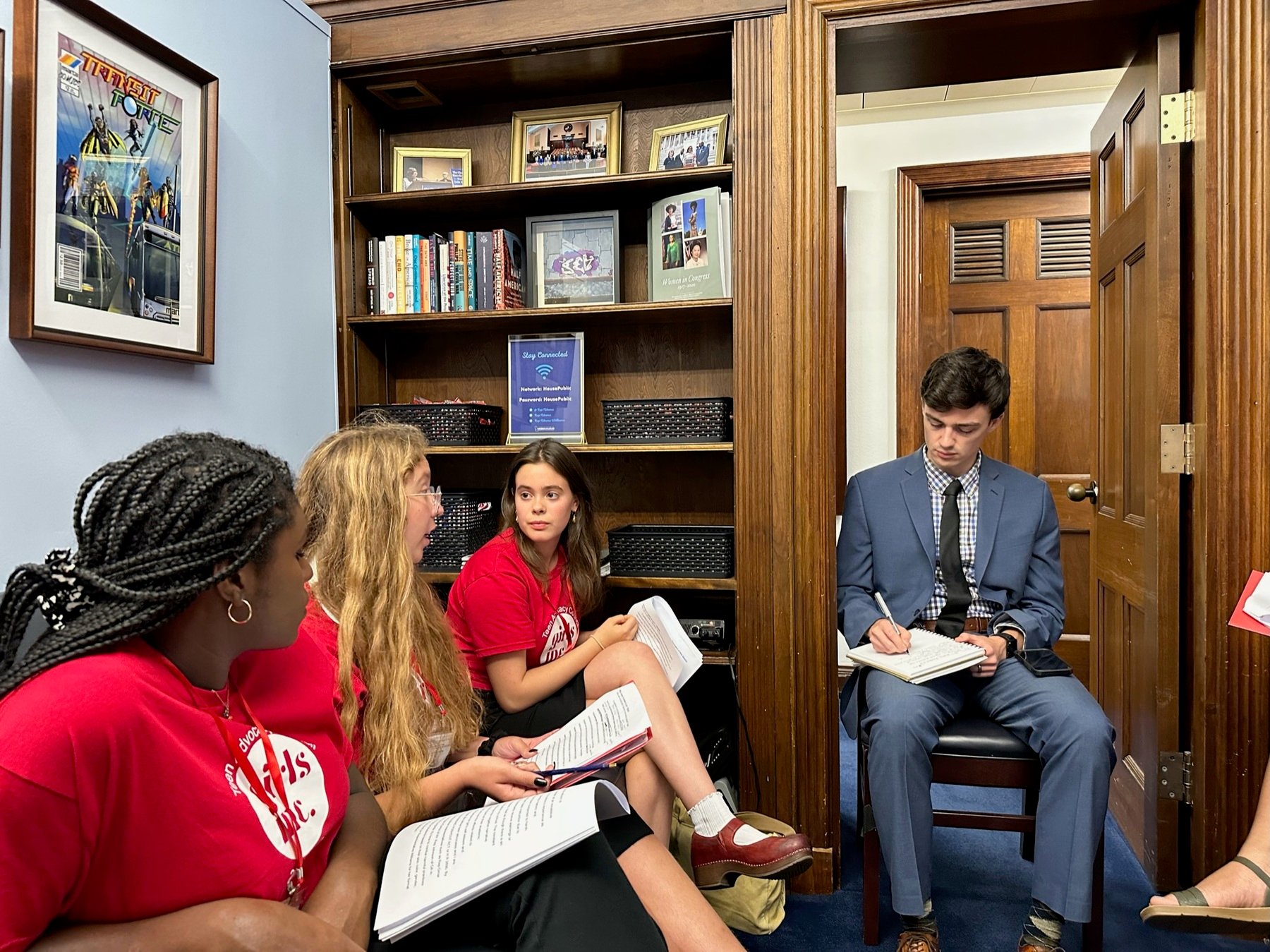

REAHYA is also drawing attention from young people. In July, Diya Kejriwal, a member of the Teen Advocacy Council of Girls Inc. — a nonprofit that started in 1864 that works to help K-12 girls reach their potential — made a trip to Washington, D.C., with other youth from the organization to lobby for the legislation.

Kejriwal prepared a presentation, complete with testimonials, about the bill and the importance of comprehensive sexuality education. The 17-year-old Georgian said that she only briefly received sex ed instruction in fifth grade and middle school. In Georgia, schools offer sex education and AIDS prevention education, but the curriculum does not have to meet the National Sex Education Standards developed by the Future of Sex Education (FoSE) Initiative, a partnership between sexual health nonprofits Advocates for Youth, Answer, and SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change.

Instead, Georgia’s sex ed instruction stresses abstinence until marriage. Last year, the state enacted a law barring divisive concepts in education generally, and this month a teacher was fired for reading a book to fifth graders about gender fluidity.

As a Georgia high school student, Kejriwal said that she’s noticed that many of her peers get information about sex from social media sites like TikTok and X (the site formerly known as Twitter) because they don’t have access to it in school.

“And that is just not accurate,” she said of the material they encounter on social media. “It’s not where kids should be getting their information from. It’s just something I’ve always felt very strongly about because it’s very clear in certain situations that people do not have accurate sexual education.”

She’s witnessed classmates ridiculing LGBTQ+ people out of ignorance, she said, and comprehensive sex ed may help to educate students and chip away at their biases.

Lee told The 19th that she is inspired by young people like Kejriwal, but she said students shouldn’t have to travel to Washington to fight for their “basic rights.”

“Health care is a right, not a privilege,” she said. “Young people want to make decisions about their own bodies, and there is no world in which they should be deprived of the information they need to do so.”

Gillian Sealy, the chief of staff at Power to Decide — which advocates for bodily autonomy, especially the circumstances under which individuals get pregnant and have children — said that not educating young people about issues such as puberty, adolescence and menstruation is tantamount to cruelty.

On July 1 in Florida, where Sealy lives, House Bill 1069 took effect. That law expands previous legislation widely known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law to limit K-12 instruction on human sexuality, reproductive health and gender identity. It also requires students and staff to solely be referred to by the pronouns that correspond with their assigned sex at birth.

“Last summer, the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe vs. Wade really opened up the floodgates to state-level bans and restrictions not just on abortion, as we thought it would, but what we’re also seeing now in terms of restrictions on sexuality education and access to reproductive care,” Sealy said. “And real people suffer. We’ve seen a huge amount of purposeful misinformation about sexual health topics, and there is real confusion and fear that this is creating.”

Sealy said that teachers now hesitate to discuss a wide range of topics with students for fear that they could be punished. This does a disservice to educators and students, she said.

Stephanie Hull, president and CEO of Girls Inc., is concerned that the lack of comprehensive sex ed mandates across the country makes girls feel it is taboo to talk about their bodies.

“What we’re trying to say is gender equity depends on bodily autonomy,” Hull said. “It depends on access for women to all rights, that education is a right, that education about your body, therefore, is a right, and we’re looking to combat harassment and violence, and we’re looking to promote menstrual equity. All of those things are part of a big picture of making sure that women stand in leadership roles and feel the power that they really are entitled to.”

REAHYA notes that marginalized youth have faced inequities in sex ed instruction and that Black students specifically are more likely to receive abstinence-only instruction, or “sexual risk avoidance” instruction, which is not as effective as comprehensive sex ed. The disparity contributes to Black students, as well as Indigenous and Latinx youth, disproportionately experiencing STIs, unintended pregnancies and sexual assaults.

Sealy said the time has come to end the myth that comprehensive sex ed will cause young people to rush into sex when research indicates the opposite. That some youth receive abstinence-only sex ed and others get comprehensive sex ed depending on where they live fuels inequity, she added. One’s ZIP code shouldn’t determine the quality of sexuality education offered to a student, she said.

While Sealy wants schools to provide comprehensive sex ed, she said classrooms are just one piece of a larger puzzle. Both parents and schools can play a role in teaching students about sexual health.

“When we teach comprehensive sex ed at school, that does not mean that somehow the parents’ role is negated,” she said. “We’re hearing that, ‘Oh, parents should be the only ones to talk to students about sex and not the school.’ Truthfully, it is a collaborative effort, and the parents’ rights and their responsibilities are in no way diminished or negated because a student can get comprehensive sex ed at school.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated what REAHYA requires.