Your trusted source for contextualizing race and education news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

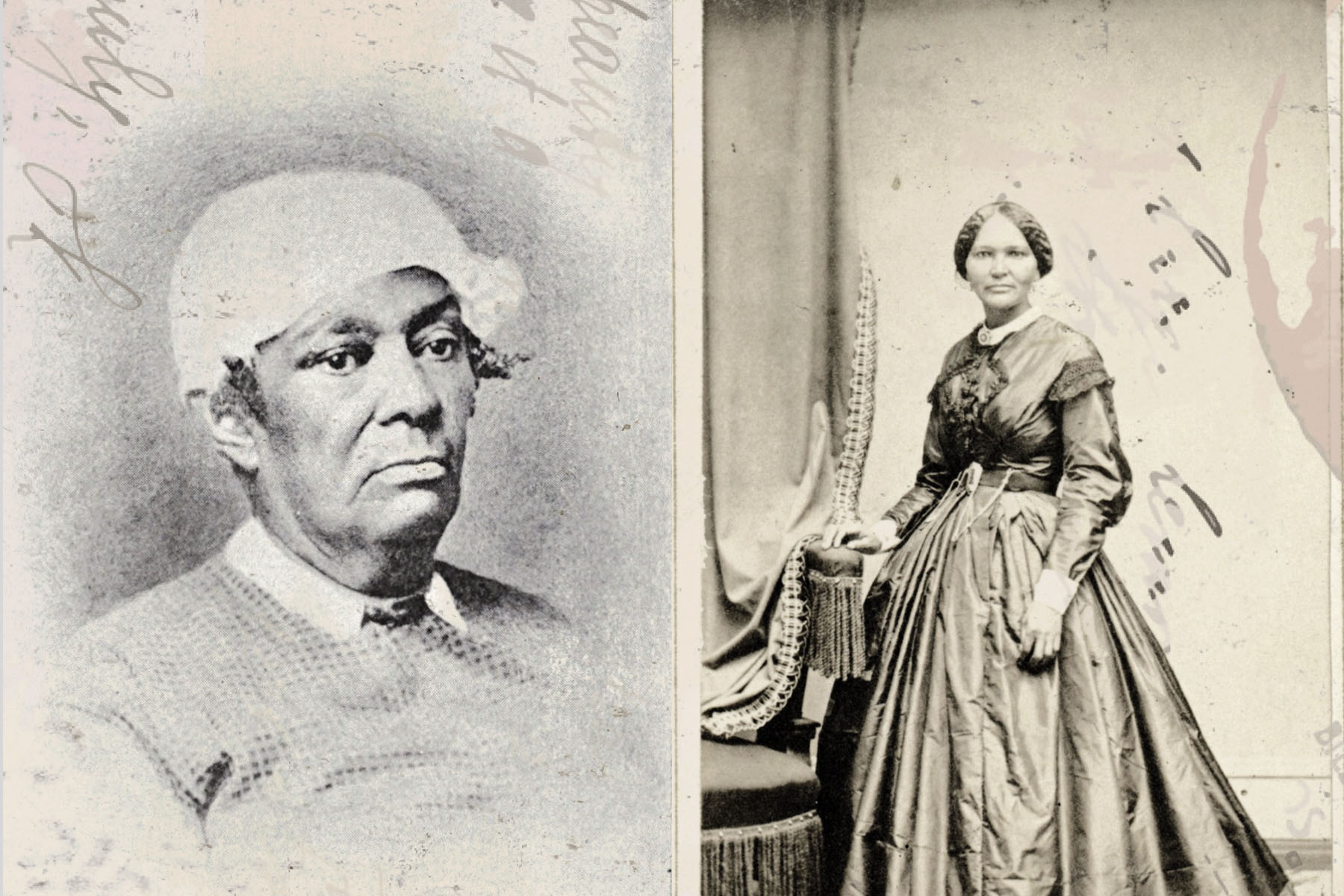

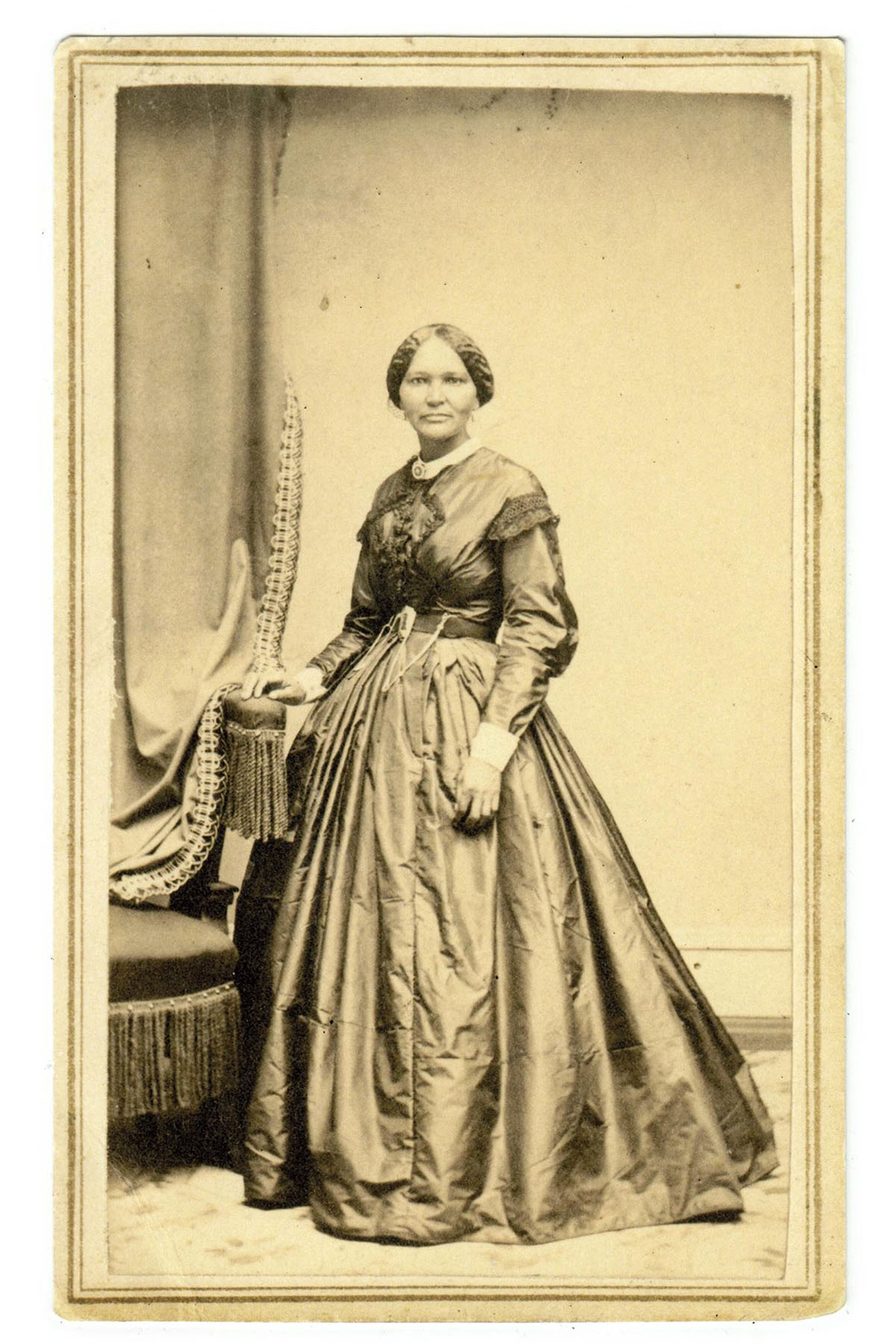

“Girlhood and its Sorrows” — the title of a chapter in Elizabeth Keckley’s 1868 memoir — does not prepare the reader for the horrors the famous dressmaker endured while enslaved as a teenager in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

To subdue Keckley’s “stubborn pride,” her mistress ordered the village schoolmaster to flog her with a cowhide and rope, and he obliged — until welts formed and blood streamed down her back. This was the first of a series of floggings meted out because her mistress, who had a “cold, jealous heart,” resented her beauty, virtue and grace. But the whippings weren’t the only cause of the adolsecent’s suffering.

“A white man—I spare the world his name—had base designs upon me,” Keckley recalls in her autobiography. “I do not care to dwell upon this subject, for it is one that is fraught with pain. Suffice it to say, that he persecuted me for four years, and I–I–became a mother.”

Despite the fact that Keckley, who would go on to become Mary Todd Lincoln’s dressmaker, suffered “savage” beatings and sexual assault, she appears on a list shared Thursday by the Florida Department of Education’s African-American history standards workgroup as an example of one of the “slaves [who] took advantage of whatever circumstances they were in to benefit themselves.”

The Florida Department of Education is drawing ire from the public, historians and high-ranking elected officials for its 2023 social studies standards that state “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

In defense of the standards, the working group released a list of 16 individuals they say personally benefited from the skills they acquired while enslaved. Four women appear on the heavily scrutinized list that has already raised questions about inaccuracies.

“This attempt to make slavery seem like kind of an apprenticeship really just seems to be an absurd way to approach it,” said Gregory Nobles, a professor emeritus of history at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “Anybody who was enslaved — they learned very quickly the rules of the game and how those rules applied to them as individuals. To live in that state of unfreedom even if it might not have been brutalizing on a day-to-day basis, sends a message to somebody about their identity, frankly, their status as human beings.”

-

Read Next:

Although historians don’t dispute that enslaved people could be highly skilled, they told The 19th that Florida’s social studies standards don’t provide a complete picture of enslavement and appear to sanitize it. They also expressed concern that the standards suggest enslavement should be credited for teaching skills to captive Black Americans, ignoring that enslaved people excelled at trades due to their own initiative and, often, in spite of their captors’ indifference or efforts to oppress them. Moreover, many of the formerly enslaved people the workgroup listed did not excel at a trade until after their release from bondage.

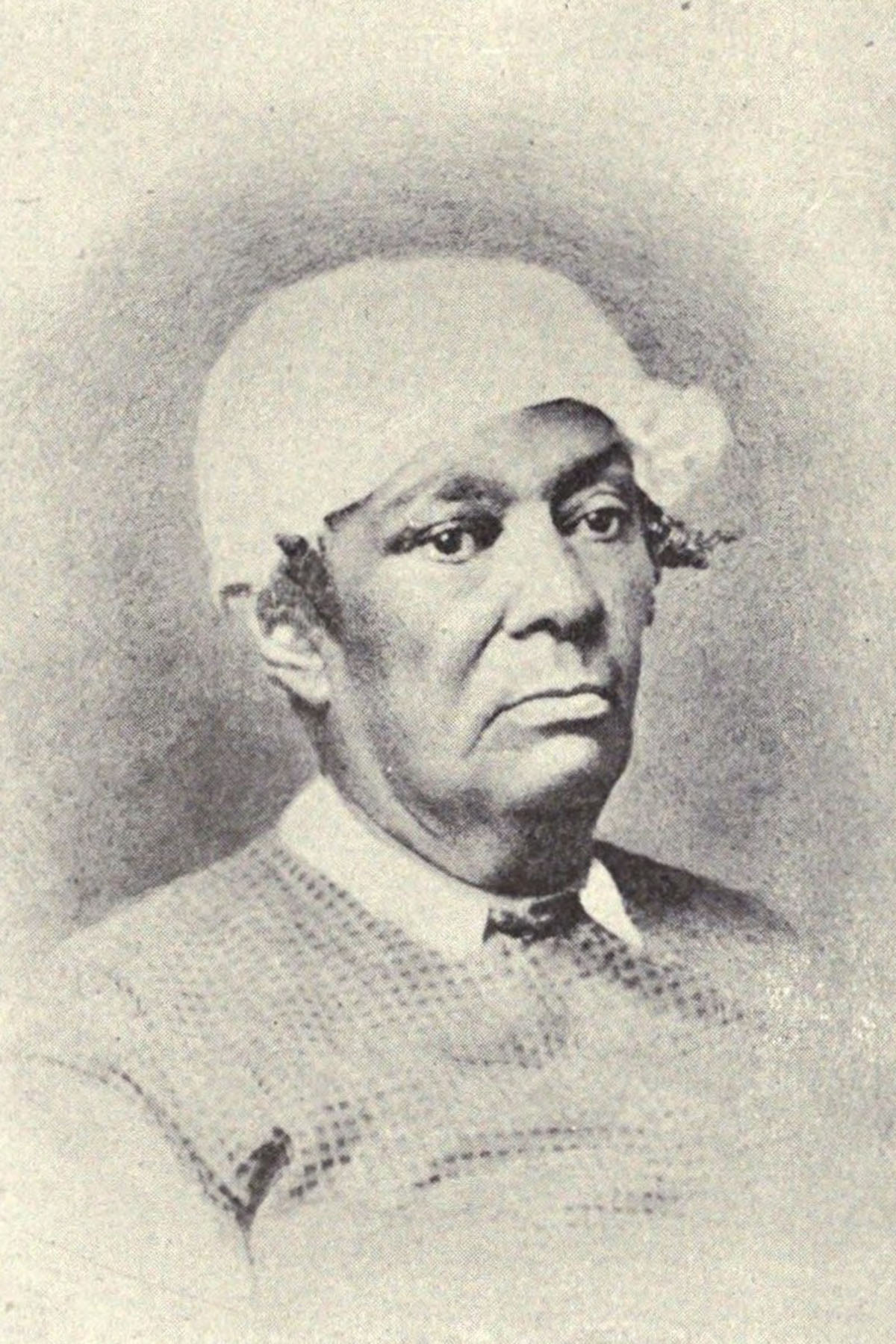

Nobles is the author of 2022’s “The Education of Betsey Stockton” about the educator formerly enslaved by the Rev. Ashbel Green, then president of what is now Princeton University. Along with Keckley, Stockton is one of the women on the group’s list.

Another woman listed — Betty Washington Lewis — was the sister of the nation’s first president, George Washington. She was White and never enslaved. It’s unclear if Marietta Carter, identified as a tailor on the list, ever existed. That leaves Keckley and Stockton as the only women named who were enslaved for certain. The Florida Department of Education did not respond to The 19th’s request for comment about alleged errors on the list.

The social studies curriculum has drawn criticism from the public and politicians on both sides of the partisan aisle. During a visit Friday to Jacksonville, Florida, Vice President Kamala Harris blasted the new social studies standards as “gaslighting” and “propaganda.”

“This is unnecessary to debate whether enslaved people benefited from slavery,” Harris said. “Are you kidding me?

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis that same day appeared to distance himself from the standards, emphasizing that he didn’t put the curriculum together. “I didn’t do it, and I wasn’t involved in it,” he said, as his 2024 presidential campaign falters financially, leading to layoffs of more than a third of his campaign payroll. “They’re probably going to show some of the folks that eventually parlayed, you know, being a blacksmith into doing things later in life,” he said of the standards.

Two of his Republican rivals in the presidential race, former Rep. Will Hurd and former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, criticized the curriculum, which has been linked to DeSantis’ 2022 Stop WOKE Act. That legislation restricts what schools can teach about race, privilege and oppression.

“Unfortunately, it has to be said — slavery wasn’t a jobs program that taught beneficial skills,” said Hurd, who is biracial, via Twitter. “It was literally dehumanizing and subjugated people as property because they lacked any rights or freedoms.”

Keckley, for one, did not learn how to be a dressmaker from her captors but from her enslaved mother. Not only were many enslaved people skilled, a number of West and Central Africans were already skilled when they were forcibly shipped to the Americas. Expertise enslaved Africans brought with them to the United States included “cultivation of indigo and cotton, knowledge of dyeing, weaving and sewing, as handwoven garments, hair styles and head wrappings, and use of color,” according to “Dress of the African American Woman in Slavery and Freedom: 1500 to 1935.” These cultural skills, passed down for generations, undermine the idea that enslavement deserves credit for Keckley’s dressmaking prowess.

Kate Masur, a professor of history at Northwestern University, put Keckley’s life into perspective. Masur wrote the introduction for the 2018 reissue of the 1942 book “They Knew Lincoln,” about the Black Americans in President Abraham Lincoln’s life, which included Keckley. After North Carolina, the dressmaker moved to St. Louis while still enslaved. There, she made gowns for many society women.

“While she was sewing in St. Louis, she was supporting an entire family of her enslavers,” Masur said. “All of her income went to supporting them as well as herself and her mother and her son. And she wasn’t able to save the money that she made from being such a skilled seamstress because all [of] that went to them, and, then, even those people who enslaved her for so long refused to allow her to become free, and they required her to buy her own freedom, rather than just granting her freedom, which was totally within their power.”

Rather than benefit from her skills as a dressmaker, Keckley was exploited by her enslavers. She could not afford to buy her freedom for the $1,200 fee — equivalent to more than $42,000 today — her enslaver set for her in 1855. In the end, wealthy benefactors raised the money to free her and her son.

Keckley later moved to Washington, D.C., where she advocated for Civil War refugees, joined the influential 15th Street Presbyterian Church and designed dresses for some of the most influential women in the nation’s capital. When her memoir was released, however, the press accused her of betraying Mary Todd Lincon, whose letters were printed in the book. Keckley denied any knowledge that the publisher intended to print the letters, but the first lady never spoke to her again, and Keckley’s influential customers turned their backs on her. Keckley died destitute in 1907 at age 89.

“It’s a good example of how, if you were a Black person living in that time period, having certain kinds of exceptional skills did not guarantee you a good life,” Masur said. “Here was this person who had made dresses for the most prominent political women in Washington, D.C., who ended her life in poverty living in what’s called the Home for Destitute Women and Children without very much of a livelihood.”

That the Florida social studies standards don’t discuss how enslavement was maintained concerns Masur. They don’t mention physical or sexual violence, family separations or much at all about how enslavers imposed bondage on people who desired their freedom, she said. If that had been the case, “Then acknowledging that some people were able to develop skills within that institution would make more sense, but without the information about how slavery was maintained, then we see just, ‘Oh, these skills for personal benefit,’ and it feels completely out of context,” she said.

-

Read Next:

Enslaved in the North, Stockton, a teacher and missionary, did not experience the brutalities that Keckley did — at least as far as the historical record shows. Born in 1798, her life was not without trauma, the first of which occurred when she was removed from her mother as a small child and given to her enslaver’s daughter and her husband, Ashbel Green, possibly as a gift or part of a legal agreement. Her separation from her mother likely “caused immeasurable trauma,” said Nobles, author of the book about Stockton’s life.

Stockton may have also been subjected to physical abuse, as Green wrote that he had to “correct” her when she was about 6 years old, but it’s unclear what form this correction took. Green was not opposed to physical punishments, as he described whipping another young Black person in his household, Nobles said.

Stockton lived in Green’s household as an enslaved person and likely as an indentured servant until her teenage years. “In 1813, she was sold or sent away to another Presbyterian pastor and three years of her life and labor were sold, a decision over which she had absolutely no control,” Nobles said. It’s not clear exactly when she was emancipated, with a number of sources agreeing that it was around the year 1817.

After her manumission, Nobles said, “She improved her situation enormously because of her own work, her own initiative, not because Ashbel Green or the institution of slavery helped her. She learned to read on her own, and she took advantage of the many, many books in Green’s library.”

As a young woman in 1822, Stockton left the United States to become a missionary to the Sandwich Islands, now Hawaii. A couple of years later, she returned to the U.S. to run the first infant school for Black children in Philadelphia and spent three decades, Nobles said, as the only teacher in the lone Black public school in Princeton, New Jersey. She died in 1865.

“She made the most of her situation,” Nobles said. “She became not just a highly educated person but an intellectual person. People talked about how remarkably sophisticated her reading was. She became a very, very effective teacher in very difficult circumstances, both in Hawaii and in Philadelphia, and certainly in Princeton at a time when educating children of color was not just dismissed, but quite often very actively discouraged and threatened.”

White supremacists targeted Black schools and Black churches with violence, and Stockton had founded both schools and what is now the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in Princeton. That she did so was an act of resistance, Nobles said. To see her story used to suggest that she benefited from enslavement has astounded the historian. He said it’s not an honest way of describing her life or that of any enslaved person, calling the social studies standards “a historical smokescreen.”

“I don’t think it’s at all surprising that people who were enslaved developed skills,” he said. “They were human beings. They had intellect. They had imagination. They were not just automatons out in the field, and I think we’ve found many instances of people like Stockton, who go on to do remarkable things. But, again, it’s not as though being enslaved is somehow a springboard for success. It was quite the opposite.”

Nobles also acknowledged how difficult it is to know the truth about enslaved people’s lives, especially if they did not tell their own stories. Most of the people who wrote contemporaneous accounts of Stockton’s life were White men, he said, including her enslaver, Green.

“I think we’ve learned as historians to be skeptical about what’s being said, especially if it’s been said by White people about Black people,” Nobles said. “There certainly can be an attempt to kind of soften or sanitize the details of the relationship. And, so, I think that’s a useful lesson for everybody in reading about these alleged success stories of enslaved people.”