Your trusted source for contextualizing LGBTQ+ news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

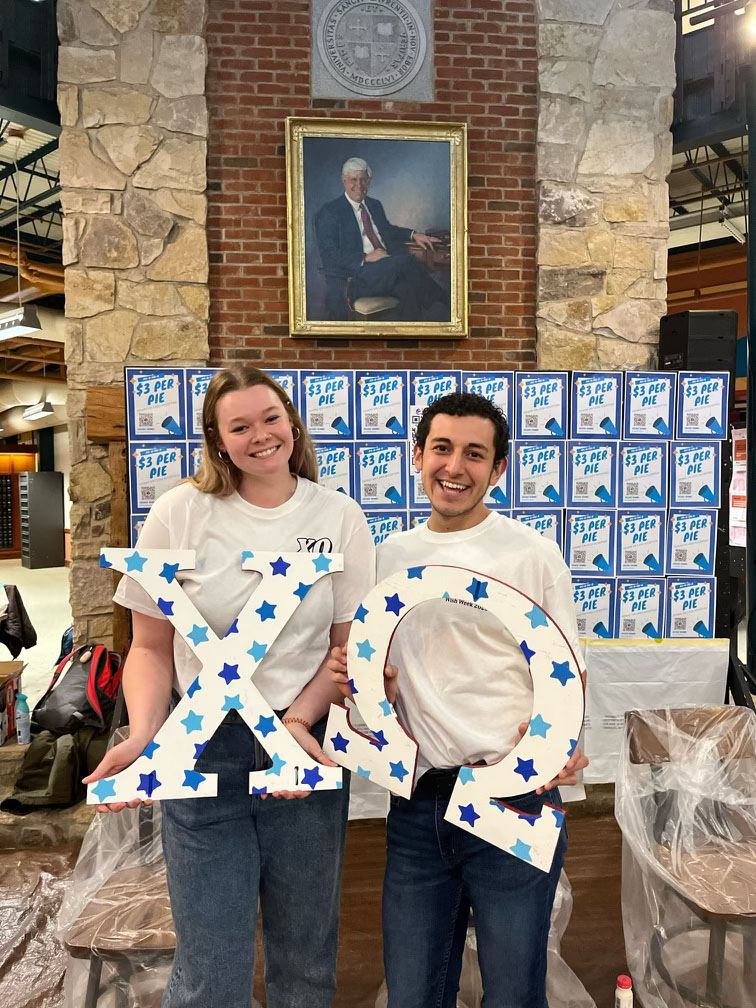

Fabián “Fa” Guzmán, 22, counts receiving a bid to pledge Chi Omega as one of the greatest things that ever happened to them.

“The feeling of happiness was indescribable because for me, honestly, I always felt attracted to the idea of being part of a sorority, but I never thought it was going to be possible. To receive that call and hear them say, ‘You’re a part of us and you’re able to join’ was one of the happiest days of my life,” Guzmán said.

Guzmán was in their senior year at St. Lawrence University — a small liberal arts college in rural Upstate New York — when they entered sorority rush in fall 2022, the first nonbinary student to do so in the history of the school. By the spring semester, Guzmán was slated to be Chi Omega recruitment chair and was hard at work planning outreach for the fall with color-coded spreadsheets and timelines.

Chi O, Guzmán thought — and regularly told prospective members — didn’t embody stereotypes they associated with sorority life. Having a nonbinary recruitment chair seemed to exemplify that.

-

Read Next:

“We’re not here to make you feel bad about who you are. We’re not here to try to change you to try to please other people,” they said. “We’re here to accept you for who you are, and we want you to represent yourself as you know. If your values match with our values, we’re here to support you.”

Then in early May of this year, Guzmán got a troubling email: Chi Omega’s national office had questions about their membership status. After a series of phone calls and Zoom meetings with national leadership, Guzmán said they were initially told that they shouldn’t have been allowed to rush, but they could retain their membership if they didn’t publicize it.

After a stressful month of exchanges, Guzmán believed they had reached a frustrating but tenable solution. But on June 2, they were notified via email that their membership would be voided immediately with no chance for an appeal.

“The selection criteria in the policy on membership includes ‘females and individuals identifying as women,’ which, by the chapter’s own understanding and your indication through the process, it is clear you did not meet the criteria at the time of joining,” the email read. “We are bound by our governing documents, and your membership must be voided.”

When Guzmán first began looking into rushing at St. Lawrence, they reached out to the university, which went on to seek official approval from each of the sororities on campus that Guzmán could rush. That included approval from the national Chi Omega organization that Guzmán, as a nonbinary person whose gender identity encompasses womanhood, qualified as one of the “individuals identifying as women.”

The 19th reached out to Chi Omega multiple times for comment, asking about the initial approval, communication between Guzmán and the national office, and the voiding of their membership.

Chi Omega’s national office provided only the following statement: “In accordance with our governing documents, Chi Omega’s Executive Headquarters recently made the decision to void the membership of an Epsilon Kappa Chapter member at St. Lawrence University. By their own admission, this individual did not meet the criteria for membership at the time of joining. Chi Omega is committed to providing opportunities for friendship, personal growth, and development amongst women from a variety of backgrounds who live and reflect the values of Chi Omega.”

To report this article, The 19th spoke with Guzmán and six Chi Omega sisters at St. Lawrence, two members of other sororities at the university with knowledge of Guzmán’s rush process, as well as members of the university’s faculty and staff, who have confirmed that the university received approval from Chi Omega’s national office for Guzmán to rush.

Guzmán said that when their membership was voided, Chi Omega national leadership told them that the organization has a two part verification system for members, requiring confirmation of either a person’s sex assigned at birth as female or authentication that a person identifies as a woman exclusively. Guzmán said this was the first time they had ever heard this policy. A recording reviewed by The 19th shows Guzmán was told about these two criteria during a June call. The recording also confirms that the national organization knew Guzmán’s was nonbinary, but was voiding it because Chi Omega would only accept nonbinary people who were “sex assigned female at birth.”

Chantel McCarthy, 20, the current secretary of Chi Omega’s St. Lawrence chapter and a rising junior, told The 19th that she was informed of this policy long after Guzmán had rushed and joined. She found out in May that Guzmán’s membership was under question with the national office at a meeting held with the chapter’s executive board and its campus adviser Nicole Casamento, who did not return The 19th’s request for comment. McCarthy said that at a different Zoom meeting on June 8, she was told that Guzmán’s membership was being voided because they did not meet these qualifications. The executive board also received guidance that in future rush cycles, the chapter itself could not ask potential new members for their sex assigned at birth during the rush process, McCarthy said. It is unclear how this verification would take place and by whom.

Because of this, McCarthy fears that the pain and hurt endured by Guzmán could easily happen again.

“I personally would never want to put someone in that position,” McCarthy said. “As much as I want everyone to be a part of the sorority, I would never want to put anyone in Fa’s shoes.”

Guzmán had no idea how they ended up here.

“I never thought I was sweeping anything under the rug,” they said. “I feel that this experience was abruptly taken from me for no reason whatsoever when they were the ones who allowed me in at the beginning.”

It wasn’t until their membership was voided, they said, that they ever heard they did not meet the membership criteria. They called Chi Omega’s statement “transphobic,” and said it reinforces “dangerous stereotypes that conflate sex with gender.” Guzmán believes this whole thing is “directly linked to the fact that I am not female-assigned at birth.”

Still, though they are set to graduate this winter, Guzmán is looking into how they can have their Chi Omega membership reinstated. They miss Chi O. All they really want to do is be a part of it.

It seemed like much of Guzmán’s life — or, in the near term, their summer — had revolved around Chi Omega.

When they found out their membership had been voided, they had just started a fellowship at the University of Arkansas, which they chose because it was the site of the founding chapter of Chi Omega. Their summer plans outside of their fellowship — centered on training future leaders in diversity, equity and inclusion efforts in higher education — were to spend time planning fall recruitment.

They were especially excited about how they could use their position as recruitment chair to connect with queer, trans and nonbinary students, as well as other international students — Guzmán is from Costa Rica. They had already established a scholarship initiative to help offset the hefty sorority dues. All this, they hoped, would help them connect with more students who assumed there was not a home for them in the Greek system. Guzmán wanted Chi Omega to welcome more people like them into “an actual sisterhood.”

“These women have actually saved my life at certain points. They have been there for me in the lowest points of my mental health. They validated my identity,” Guzmán said.

Guzmán first became friends with many Chi O sisters when they were a resident adviser. Some of Guzmán’s former residents rushed and pledged the sorority, and Guzmán enjoyed visiting the Chi O house, their presence so regular that they were often jokingly referred to as an honorary sister.

In May 2022, these friendships became a refuge for Guzmán after a traumatic personal experience strained their mental health. Guzmán’s Chi O friends said they could stay with them at the sorority house for support.

While living at the Chi O house, Guzmán said, they began to “embrace” their nonbinary identity. They had arrived on campus identifying as a gay cisgender man. As they spent time with the Chi O sisters, Guzmán discovered strong feelings of identification with the kind of womanhood Guzmán saw embodied in sorority life and at Chi O. They had previously felt “hesitant” about accepting that part of their identity, but the support and sense of connection they found in Chi O changed that.

“I have a very conservative Latin American background, and coming out as gay was already a huge deal in my family years ago, and it took us years to heal and reach a point of acceptance and love and support,” Guzmán said.

It’s what made the thought of coming out again, this time as nonbinary, all the more intimidating.

“It was scary for me, because I felt I wanted to explore this but I was thinking, how am I going to explain this in Spanish when I’m already so different in English?”

Ultimately with the support of the Chi O sisters, they ultimately came out as nonbinary at the end of May 2022.

As a base definition, nonbinary applies to people who do not identify exclusively as a man or a woman. But the gender identity and expression of nonbinary people is varied and unique to the individual — some nonbinary people do not identify as either a man or a woman, but completely outside of those genders.

Guzmán describes themselves as gender fluid, meaning that they identify as a woman within their gender identity. Their identification with womanhood as a concept was not only what made them want to be a part of a sorority, but led them to believe that under Chi Omega’s policies, they were fully within their rights to be included as a member.

Guzmán said they remember thinking, “I’m doing this for me. I’m doing this because this is who I am.”

After they came out, the idea of Guzmán rushing was floated, both by Chi O sisters and by Guzmán themself. Guzmán reached out to St. Lawrence’s Greek life adviser, which kickstarted the lengthy process of getting sign-off from all four of the sororities. One week before rush began in fall 2022, Guzmán received approval from St. Lawrence to rush at three of the four houses, including Chi Omega, based on the verifications that the school had received from the Greek houses and their respective national organizations or local governing chapters.

In less than a year, Guzmán had made their presence deeply felt within Chi O, representing the chapter at national and regional trainings. Their membership was well-known within the national office, Guzmán and the six Chi O members told The 19th. As a prominent student leader — Guzmán is president-elect of the Omicron Delta Kappa leadership honor society — their name had become somewhat synonymous with Chi O on campus.

Molly Doyle, 20, came to St. Lawrence from Hailey, Idaho. As a queer woman, Doyle had been concerned about joining a sorority, even if it seemed like an easy way to make friends on campus after coming out of COVID lockdowns. She initially rushed during the fall of her sophomore year, the earliest a student can rush at St. Lawrence, and withdrew after feeling overwhelmed with concerns about whether a sorority could offer a safe space for queer women.

In the spring, she met Guzmán, and her opinion changed. Talking with Guzmán — especially about their vision for the future of Chi O — made Doyle understand sororities differently. Chi O, especially, seemed like a special place; many other sisters were LGBTQ+, many were, like her, majoring in STEM-related fields. She felt like she didn’t have to meet the stereotype of a “sorority girl” to belong.

“The fact that Fa was really in this sorority really tipped it for me,” Doyle told The 19th. “I was like, ‘Yeah — this is going to be an inclusive, amazing space.’”

Kayla Minst, 21, is a rising senior and the current personnel chair for Chi Omega at St. Lawrence. She also was excited about Guzmán’s place at Chi O and what it signaled. As a Black woman, she hopes that the future of Greek life at St. Lawrence and nationally is “more inclusive, not just with gender but with race.”

“When you stereotypically think of a sorority girl, you have an image in your mind and it’s going to be pretty similar to what everyone else thinks, and I would really like for us to really reflect on this,” Minst said.

Guzmán said they had received positive feedback from the national organization for the work they were doing as recruitment chair at Chi O. Recruitment numbers for the chapter ahead of fall rush were already surging, and they had received praise from the national office for the scholarship initiative they had founded as well. Their life as a sorority sister was everything they had dreamed it could be.

In the spring of 2023, the St. Lawrence alumni magazine was set to run a story about Guzmán’s leadership on campus. Not only was Guzmán the first nonbinary student to rush and pledge a sorority at the university, but they had almost immediately risen to a leadership position in their sorority. Guzmán reached out to Chi Omega’s national office to let them know, following Chi Omega’s policy to get approval before naming the organization in any outside media.

The story was also going to mention the research that Guzmán was doing with Alanna Gillis, an assistant professor of sociology at St. Lawrence, on Guzmán’s experience being nonbinary and participating in Greek life.

But then Guzmán’s membership was first questioned, and then ultimately suspended. Gillis first found out about Guzmán’s membership status just as Guzmán started the back and forth with the national office, which had seemingly sprung to action after the magazine piece was on its radar.

“They had to tell me because we were doing research together and basically had to stop the research project, because our research was entitled ‘Breaking Down Barriers,’ and now all of a sudden some new barriers were coming,” Gillis said.

As part of this study, Gillis interviewed a number of students and staff at St. Lawrence about Guzmán’s rush process. Through these interviews, Gillis confirmed that staff at the university had reached out to all the sororities with presences on campus and received permission for Guzmán to rush as a nonbinary student.

Just after Guzmán told Gillis it looked like their membership would be able to stand, albeit quietly, they found out it had been voided. “It was devastating, because from the extensive research that we had done and talking to so many people, we know that they did everything right.”

Bela Cheung, 22, graduated from St. Lawrence University last month. Cheung said she spent close to two months sending emails to the national Kappa Kappa Gamma office trying to get a firm answer on whether Guzmán would be able to rush. Ultimately, Cheung said the university told Guzmán that they would be able to formally rush all the houses but Kappa Kappa Gamma.

Cheung said that several months following fall rush, representatives from the Kappa Kappa Gamma national office visited St. Lawrence. Cheung asked them about the situation with Guzmán, and the national representatives told her that of course they could have rushed. Cheung said she recalls thinking, “Great — that would have been awesome to hear a few months ago.”

Anna Sandt, 22, also just graduated from St. Lawrence University. While there, she was a member of Kappa Delta Sigma, the only sorority on campus not affiliated with a national organization. The chapter unaffiliated from the national organization in 1969, after the campus chapter wanted to extend a bid to a woman of Asian descent, to the opposition of the national office.

Sandt told The 19th that St. Lawrence’s Greek life adviser informed her sorority that Guzmán wished to rush and would need the house’s permission to do so. Sandt said the chapter had a meeting about establishing a policy allowing nonbinary students to rush, and the house voted in favor of it.

“We wanted to invite them into our shelter,” she said. “It was important for us to create an inclusive environment and basically a safe network for any individual that felt like Kappa Delta Sigma would be like a home for them.”

St. Lawrence University asserts its commitment as a place where inclusivity matters.

“This issue is one that we understand the campus chapter’s leadership is navigating with the national Chi Omega organization,” the university said in a statement. “St. Lawrence University supports the identity of every student, and our Student Life team is here for all of our students grappling with issues of inclusion and belonging.”

Today, Guzmán feels confused and hurt.

“I’m able to connect with women and womanhood, why is there any issue for me to not be able to join?” Guzmán wondered. “I don’t identify solely as male, I’m just here being both at the same time.”

What had once felt like “this great opportunity for the nonbinary and trans community to just feel included in these spaces that stereotypically are only for cisgender White women who are rich” now has become an experience laced with pain, they said. But Guzmán and their fellow sisters aren’t giving up.

Courtney Lynn, the vice president of St. Lawrence’s Chi Omega chapter, is now a rising senior. She told The 19th that the current executive board has discussed taking the issue of nonbinary members joining to at the national Chi Omega convention next summer, asking for a vote on an official change to the bylaws. But until then, there’s not a lot they can do.

“It feels like we’re doing nothing, and that hurts a lot,” she said.

In Lynn’s dream world, the national organization would issue an apology, reinstate Guzmán’s membership and promise to change the membership policy to be more inclusive.

“I think it doesn’t matter what your sex assigned at birth is, in any way. That should never come up,” Lynn said. “It’s how you choose to define yourself and if you align with our morals and our values and womanliness in some way, then I think that should be enough. That should be more than enough.”

McCarthy, the current secretary of Chi Omega at St. Lawrence, said that instead of Guzmán having their membership voided, she wishes they could instead be the chapter president. McCarthy would also like to see their chapter request a bylaws change at the national convention next year. She wants to “be loud.”

“I wish I could trade places with Fa,” McCarthy said. “My heart goes out to them so much. I never want to see this happen again. I want to see visibility. I want to see clarity. I want to see support. And I want to see pride for all the members of the LGBTQ community and all nonbinary people. I just want to advocate for change now.”

Guzmán is processing all the feelings that this past year, and past few weeks especially, have triggered. But true to their reputation as a beloved leader and friend, they are also looking ahead to how they can translate their pain into change.

“I am hopeful that my story is able to provide comfort and visibility to an issue — I just want people to realize that nonbinary trans folks? We are here. We want to stay in this lane. We’re just looking for a space to belong,” Guzmán said.

Guzmán said that they feel deeply frustrated that after feeling so much hope, they now find themselves wondering what the road to real change will look like and how long it may be. For now, they have one semester left of college. They are already thinking about a career in higher education and how to “open doors for students that share one or more of the identities I have, to make students feel like they belong. I want to continue to be an advocate. I always say that after a very unfortunate situation, hopefully an activist is born.”

Guzmán is grieving — a loss of support, of identity, of sense of achievement. But they have comforted themself during this difficult time with their personal motto:

“We are here to stay and slay.”

Have you had any experiences with either inclusivity or discrimination based on gender identity or sexuality within the Greek system at your college or university? Email Jennifer at [email protected]