What do you want to know about politics? We want to hear from you, our readers, about what we should be reporting and how we can serve you. Get in touch here.

TAHLEQUAH, OK — Kim Teehee can trace her ancestors on a scattered tour of the South — in Georgia, up the Carolinas and through Tennessee. If a single place can divide a family’s story in two, then for Teehee’s it might be Blythe Ferry, a crossing point for the Tennessee River at the northwest corner of the Cherokees’ ancestral homeland, now Tennessee.

“They moved across the water, basically symbolic of saying goodbye to the homelands forever,” Teehee said.

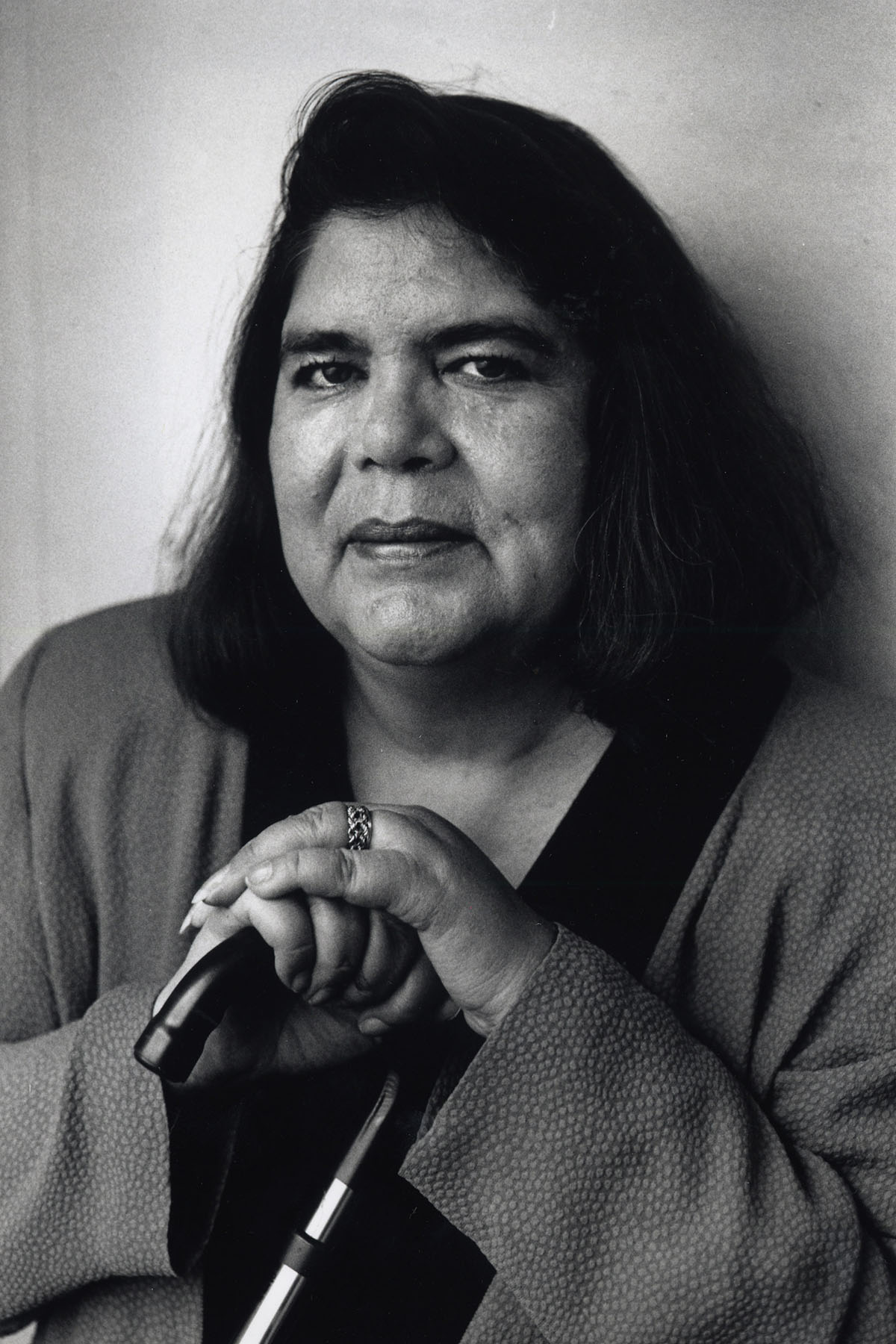

She recalled her ancestors’ brutal and often deadly journey from her office in eastern Oklahoma, the end point of what became known as the Trail of Tears — ᎠᎩᎵᏱ ᏗᎨᏥᏱᏄᏍᏔᏅᎢ — for thousands of Cherokee people forcibly removed from their home.

Flanked by a traditional Buffalo grass doll and sipping a Diet Coke, Teehee traces the long thread of U.S. federal action that shaped the next chapter of her family’s story: Federal action brought her family to a nearby town that’s been marked by poverty and poor health. A federal program to assimilate Native American children took her parents to a boarding school, and another sought to urbanize them with work in Chicago. Federal dollars would fund the preschool she attended and the hospital where her parents built careers.

Cherokee people and their tribal government, Teehee believes, should have always had a seat at the table where these decisions were made: The very treaty that saw her ancestors forced off their lands almost 200 years ago also promised Cherokee people a non-voting delegate seat in the U.S. House. Now, the Cherokee Nation and Teehee — who was appointed to the job by the tribe’s leaders — are mounting an aggressive campaign to see that promise fulfilled.

The Cherokee Nation’s efforts to sit Teehee in the House have bipartisan support, but it’s not immediately clear when or how congressional leaders will take up the issue in earnest. If she gets this seat, with spots on key panels and the power to speak on the House floor, Teehee hopes to help shape the next chapter of federal policy to benefit tribal governments and the people they serve. That includes addressing the epidemic of violence against Native women, saving the Cherokee language from extinction, and protecting funding for health care and housing.

“We are matrilineal people. …The fact that the first delegate to be seated is a woman — that’s obvious to Cherokee culture.”

“ᏂᎦᏛᏉ ᎠᏂᎨᏯ ᏧᏂᏴᏫ ᎢᏗᏜ ᏭᏂᎩᏓ ᎠᏂᏴᏫ, …ᎾᏍᎩᎤᏙᎯᏳ ᎢᎬᏱ ᎦᏅᏏᏓ

ᎠᏥᎪᏗ ᎨᏒ ᎠᎨᏯ – ᎾᏍᎩ ᎬᏂ ᎠᏂᏣᎳᎩ ᎤᏂᎲ ᎢᏳᎾᏛᏁᎵᏓᏍᏗᎢ.”

Taralee Montgomery

“As a foundational matter in my life story, it’s important to appreciate that so much of federal Indian law and policy in this country has so directly impacted my family, personal story and my journey,” Teehee said. “I didn’t see it as a young girl, but much later I could appreciate it all.”

The Cherokee Nation is the country’s most populous tribe, at 450,000 citizens. Teehee’s seat in Congress would mark the beginning of a new kind of relationship between the federal government and the Cherokee Nation, along with the tribal governments of the 573 other federally recognized tribes. That the first delegate from the Cherokee Nation would be a woman in a men-dominated chamber would also send a public message about the tribe’s values.

“We are matrilineal people. It informs a lot about how we care for our families, and empower all generations of women to lead,” said Taralee Montgomery, a senior policy adviser for the Cherokee Nation told The 19th. “The fact that the first delegate to be seated is a woman — that’s obvious to Cherokee culture.”

Montgomery, 31, has worked alongside Teehee for six years and described her as an “absolute force.” Montgomery had just unveiled a new room designed to accommodate breastfeeding parents who work at the Cherokee Nation’s offices in the tribe’s capital of Tahlequah or visit the building for government services, part of the tribe’s efforts to make its government more family friendly. She credited Teehee with empowering her to pursue the project. “She means so much to young people like me,” Montgomery added.

Montgomery said that until recently, many Cherokee people didn’t know about the provision of the 1835 Treaty of New Echota promising a Cherokee delegate. Since the campaign to seat Teehee kicked off last fall, interest in seeing the treaty fulfilled has been building among Cherokee people.

“The thing about Kim Teehee is that she will never meet a challenge that she won’t take on and conquer,” Montgomery said. “That tells you a lot about her role as a delegate.”

The Durbin Feeling Language Center, which opened last year, is housed in what used to be an old casino on the southern end of Tahlequah. The immersive space, used to teach the Cherokee language to children and adults, exudes joy, but also urgency. In 2019, Cherokee people declared their language to be under a state of emergency, headed for extinction.

Of about 400,000 Cherokee people living in the United States, a survey found that just over 2,000 can speak Cherokee fluently. Most of those speakers are over the age of 40, and every year, there are fewer. Just 50 families are estimated to speak Cherokee at home.

Teehee doesn’t speak much Cherokee, though her parents both grew up speaking it almost exclusively at home in the land allotments assigned to their families by the federal government near Stilwell, Oklahoma, about 30 minutes outside Tahlequah. On the grounds of Salem Baptist Church in Stilwell, rows of headstones mark the graves of Teehee’s family members.

Why Teehee is not fluent in Cherokee can be traced back to federal policy — more specifically, a program that sought to urbanize Native Americans with the promise of work opportunities far from their reservations. The federal dollars that helped fund the Durbin Feeling Language Center are the beginning of the effort to repair the harms from that policy, and it’s personal for Teehee.

Teehee’s parents met at Sequoyah High School, which at the time was a U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school. They weren’t prohibited from speaking Cherokee — a rule at many such schools — but it wasn’t useful in communicating with students who hailed from different tribes from across the region.

Teehee’s dad eventually dropped out to enroll in a federal work relocation program that took him to Chicago, where Teehee was born and spent the first decade of her life.

“The idea was to relocate you to find new opportunities. Its intent, though, from Congress, was to assimilate you into mainstream society,” Teehee said. “There’s a saying that has its origins in the Indian boarding school era, which is, ‘Kill the Indian, save the man.’”

Chicago became one of the largest hubs of relocated Indigenous Americans in the United States. Teehee grew up understanding she was Cherokee, but the opportunity for work in Chicago afforded to her parents meant the loss of formative years in her own Cherokee community. Through his job, Teehee’s dad was able to complete his high school diploma, which helped pave the way for a trade job back home in Oklahoma, where the family yearned to be.

Many of those at the Durbin Feeling Language Center have similar family stories: They didn’t grow up speaking the language at home but want to learn now; they want their own children to grow up fluent.

Kristen Thomas, who leads a program that pairs native Cherokee speakers with hopeful students, notes that the building itself is an immersive experience in the Cherokee language. Every sign and every book inside the 52,000-square-foot facility — from the label on the fire extinguisher to a storybook about the solar system — is written in Cherokee to serve its preschool through 8th grade language immersion school and its adult apprentice program. When its day care center opens later this year, the babies too will hear only Cherokee.

The school’s main purpose is to create new Cherokee speakers, but it is also a hub to foster pride for Cherokee culture. Inside the school’s gym, there is a stack of wooden sticks with loops on one end used to play stickball, a sport played by several North American Indigenous tribes that was the precursor to lacrosse. Another space holds a demonstration kitchen to preserve traditional Cherokee recipes, like ᏒᎩ & ᏧᏪᏥ, a dish made up of wild onions prepared with eggs and animal fat.

The center was made possible by a combination of Cherokee Nation funds and federal dollars. Earlier this year, President Joe Biden signed a law that funds a federal survey of both Native language use and the funding needs of language revitalization efforts. It shares its namesake with the center: Durbin Feeling was the Cherokee linguist who helped add the Cherokee syllabary to word-processing technology.

“This is such an obvious placement and way to strengthen the partnership with Indian country.”

Kristen Thomas

“ᎯᎠ ᏄᏍᏛ ᏯᏛᎿ ᎬᏂ ᏫᎦᎧᏅᎯ ᎠᎴ ᎠᏟᏂᎪᎯᏍᏙᏓ ᏳᎵᏍᏙᏗ ᏱᎬᏁᏗ ᎾᏍᎩ

ᏗᎵᎪᎯᏍ4Ꮧ ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᏍᏛ ᎠᏰᎵ ᏂᎬᎾᏛᎢ.”

Thomas said that federal support for Cherokee language revitalization efforts is crucial, given that language is “the lens through which we view the world.” She described Teehee as an obvious choice to represent Cherokee people in Congress, and urged House lawmakers to take action.

“There’s that we deserve it, and that we’ve been promised this,” Thomas said. “But even without that, this is such an obvious placement and way to strengthen the partnership with Indian country.”

Teehee said the effort to protect Native American languages would be one of her priorities as the seated Cherokee delegate to Congress. The Cherokee Nation believes that federal support to protect the language would help directly address its own damage to Native American language and culture.

“I always say I’m a product of federal Indian policy and relocation, getting us to another state where acculturation was the goal,” Teehee said. “But I’m also a product of its failure because the program highly underestimated the attachments that Indians have towards their communities and our families.”

While in college, Teehee joined the Cherokee Nation’s government office to work as an intern under Wilma Mankiller, the first woman elected as principal chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Mankiller, who died in 2010, became Teehee’s longtime mentor. Teehee described Mankiller as an exacting boss who nevertheless taught her to be patient when listening to people’s struggles and to welcome them with empathy.

In 1985, Mankiller had become just the third chief elected to the role since Cherokee people regained the power to elect their own chiefs in the 1970s. During her tenure, Mankiller reshaped the tribe’s relationship with the federal government to protect its sovereignty, and focused on health care and women’s leadership.

Mankiller, in a speech at Emory University, told a story about an encounter between Cherokee people and a United States treaty negotiation team. The U.S. cadre was made up of all men, prompting the Cherokees to ask, “Where are your women?”

Teehee had been set on going to medical school, but Mankiller urged her to attend law school. Afterward, Teehee felt pulled to a career advocating for the power and sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation and its people. She decided Washington, D.C., was the place to do it after hearing one of the tribe’s staffers describe quashing what they considered anti-Indian legislation in Congress.

In 2009, after a decade working on Native American issues in D.C., Teehee would be tapped for her highest-profile job to date, as the nation’s first-ever senior policy adviser for Native American affairs under the administration of President Barack Obama. In that role, she pushed for legislation that would strengthen accountability for people who commit crimes against Native American women.

More than 4 in 5 American Indian and Alaska Native women — 84.3 percent — have experienced violence in their lifetime; more than half have experienced sexual violence, according to a 2016 federal study. Murder is the third leading cause of death for Native American women.

Advocates have long criticized federal and state law enforcement agencies for not doing enough to respond to missing person reports and reports of violence related to Native American women and girls.

The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center blames the high incidence of violence against Indigenous women on the erosion of tribal sovereignty and a complicated justice system facing victims and their families that has allowed perpetrators to move on without facing accountability.

“In the 1970s and ’80s, as tribes are starting to grow more economically, and creating more jobs, and creating resorts and casinos, and hotels and golf courses, that’s inviting more non-Indians on the reservation. When you don’t have criminal jurisdiction over that non-Indian, that’s an enormous gap,” Teehee said.

“And then when you combine that with the fact that, you know, probably about half of Native American women are married to non-native spouses, you leave an environment that’s vulnerable for the rates that we have of domestic violence in Indian country.”

A tool to combat those astounding rates of violence was included in the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act. It gave tribal governments power to prosecute non-Indigenous people who commit domestic violence or dating violence against Indigenous women in Indian country.

Teehee said the measure found a receptive ear in Congress in part thanks to her years of relationship-building and education on Native American issues with lawmakers and congressional staff.

After a stint at the Democratic National Committee helping the party navigate its relationship with Native American tribes and advocacy groups, Teehee pivoted to Congress in 1998, becoming a senior adviser and the sole staffer for the first Native American Caucus in the House.

The caucus worked to educate members on Indian issues, “as well as try to kill anti-Indian proposals,” Teehee said. Often positions that weren’t favorable to Native American tribes came from lack of information about how proposals would impact them.

“I felt that that was my job to fill gaps,” Teehee said. “If you don’t have time to get to know an issue, you can’t write about it for your boss, I will do it. And I don’t need credit for it. I’ll give you a letter. I’ll give you a memo. I’ll set up meetings for you. I’ll give you backgrounders.”

When the time came for negotiations surrounding the Violence Against Women Act and the provisions dealing with tribal jurisdiction in 2012, Teehee said, the administration had a Congress that was really informed and supportive of issues impacting Native American people.

“If we don’t do it now, we’re going to lose that learning curve,” Teehee told the administration at the time.

While she’s not a seated delegate in Congress, Teehee has continued advocating on behalf of the Cherokee Nation in Congress and before the White House. Last year, Biden signed a reauthorization of the same law that expanded the list of crimes over which tribal governments have jurisdiction to include sexual violence, sex trafficking and stalking.

It’s ongoing work. Teehee said that the list of issues impacting tribal governments is long and the list of champions in Congress is ever fluctuating. The next battle for tribal governments will be to secure funding for their most basic operations. About 90 percent of all federal funding that flows to tribal governments is discretionary and subject to constant reauthorization. Teehee has been advocating for that funding to become a permanent expenditure, and out of reach of politicking or a government shutdown.

“That’s education, that’s housing, that’s food,” Teehee said.

Set back from a busy commercial street by a lush green lawn in the heart of Tahlequah, sits an ornate two-story brick building. This structure replaced a wooden one that burned down during the Civil War and was finished in 1869 — 40 years after the forced relocation of Cherokee people to this land — and became the Capitol of Cherokee Nation. In the 1900s, when Oklahoma became a state and the federal government sought to dissolve the tribal governments, the Cherokee legislative body lost its power and the building became property of the local county government. Cherokee people wouldn’t elect their own chief for another 70 years.

One question that comes up often in discussions about seating a Cherokee Nation delegate in Congress is why it took nearly 200 years for the tribal government to name someone to the post and move to formally seat them in Washington.

“When we get to our new homeland, we are simply trying to survive and rebuild a great society,” said Chuck Hoskin, the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. Like the old Capitol, now the Cherokee history museum, Cherokee people would go through periods of destruction and disempowerment for the next 150 years.

In the 1970s, when Cherokee people elected their first principal chief, and the federal government gave the tribe more financial autonomy, Hoskin said a period of rebuilding began that led to the moment the tribe finds itself in now — where it has the political connections and resources to demand its seat in Congress.

Hoskin, who was reelected to the job last earlier this month, oversees the tribe’s government.

Those efforts appeared on the brink of success at the end of last year, following a months-long public campaign to pressure the United States to fulfill its treaty obligation, including intense lobbying of congressional leaders and dozens of interviews with the press. The campaign gained momentum from a congressional hearing in November, where lawmakers of both parties acknowledged the treaty and expressed support for exploring different avenues to seat Teehee. Support rose the highest ranks, when then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi committed to finding a “path” to welcome a Cherokee Nation delegate into the House.

Republican Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, who now chairs the panel handling this issue, the Rules Committee, called Teehee “a very good friend” during the hearing..” Cole’s office did not respond to a request for comment about when his committee may take up the issue again.

An aide to Rep. Jim McGovern, the highest-ranking Democrat on the panel, who spearheaded the November hearing, said McGovern continues to believe that a Cherokee Nation delegate should be seated in the House and reaffirmed the lawmaker’s commitment to advocating for the issue.

The aide said McGovern was frustrated that the issue didn’t advance in the 117th Congress.

Into December, Teehee and the Cherokee Nation’s leaders held onto hope that Democratic leaders would act on the issue before their time in the majority ran out. They did not.

The House’s new GOP majority meant the Cherokee Nation’s delegate campaign had to start over in the work of educating lawmakers. They also needed to address outstanding concerns, which boil down to four critical questions.

The first and most consequential is whether seating the Cherokee delegate can be done with a simple House resolution, or if the process will require approval from the Senate and the president — a lengthier and more politically involved process.

“I feel it now just talking about it — how proud I am to represent my nation. But then I can’t help but think about what we lost in the process, too.”

“ᎠᏴ ᎾᏉᏃ ᏂᎦᎵᏍᎬ ᏍᎩᏉ ᎧᏃᎮᏗᏊ ᎨᏒᎢ – ᏰᎵᎦᏯ ᎠᏴ ᎠᏩᏢᏉᏗ ᎾᏍᎩᎾᎢ

ᎠᏰᎵ ᎦᏥᏕᎸᏗᎢ. ᎠᏎᏃ ᎠᏴ ᎦᏓᏅᏖᏍᎬ ᏄᏰᎵᏛ ᎢᏳᏍᏗ ᎢᎩᏲᎱᏎᎸᎯ ᎾᏍᎩ

ᏂᏧᎵᏍᏔᏅᏍᏔᏅᎢ, ᎾᏍᏉ.”

Kim Teehee

Second, some lawmakers have wondered whether Congress should have a delegate who is appointed. The House’s delegates representing U.S. territories are elected, but Teehee was appointed by the Cherokee Nation’s tribal government. (The Cherokee Nation says it’s within its sovereign rights to decide how it picks its own representative.)

The third is whether sitting Teehee would give double representation in Congress to Cherokee people, who are already technically represented by whoever their local representative is.

Lastly, Congress would also need to decide how to handle the claims made by other Cherokee bands to the delegate seat. On the side of Tahlequah’s main artery, a large ad on a bright electronic billboard shows a Cherokee woman alongside a plea to Congress to seat a Cherokee delegate. But the woman is not Kim Teehee — it’s Tori Holland of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians of Oklahoma, which has its own treaty claim to a delegate seat in Congress. There may be another.

All are questions that Cherokee Nation lawyers and the Congress’ research arm have studied.

“It’s an enormous undertaking to educate again” Teehee said. “I feel like I’m back at being that staffer that used to research, write memos, write letters, write colloquies, figure out how to message D’s and to R’s. You know, I’m back in that space again. ”

Just outside the lawn of the Cherokee History Museum in a busy part of Tahlequah is a sitting area and art installation lush with lavender and ornamental grass. Tall murals feature the work of Traci Rabbit, a Cherokee artist who says her work tries to capture the essence of the Native American woman: “From the proud lift of her chin to the strands of hair caught in the wind, she appears to weather all storms.”

It’s sunny, the bright colors of the murals are popping, and the women in them seem to float above the ground. The mural behind where Teehee sits for our interview is called “Cherokee Traditions” and shows a woman wearing a traditional feather cape; only a handful of Cherokee artists who can make them are left.

If her bid to be seated as the delegate from the Cherokee Nation to Congress comes to fruition, Teehee said, the moment will be bittersweet:The cost was the home, lives and tears of her ancestors. Hundreds of thousands of Cherokees never saw the promise fulfilled.

“I feel it now just talking about it — you know, how proud I am to represent my nation. But then I can’t help but think about what we lost in the process, too,” Teehee said.

If she gets to take the oath of office, Teehee will place her hand on her own Bible, written in the Cherokee language. Her first choice would have been one of her grandfather’s old Cherokee Bibles, but so many of the family’s documents and books burned to ash in a 2016 house fire — including a little green Cherokee hymn book cherished by her dad. The sound of Cherokee hymns remind Teehee of traveling to her parents’ home for family funerals.

Her parents are now in the late 70s and suffering from serious illnesses. Teehee said they continue to be a key source of motivation for her work.

“I think of how proud I would be for my parents to be able to be there with me and to be alive to see it as Cherokee speakers. I just hope it does happen in their lifetime.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled the name and affiliation of the school Teehee's parents attended. It was Sequoyah High School, and the boarding school was run by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. The article also misstated the type of federal dollars used to fund the Durbin Feeling Language Center; it is U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs child care dollars. The article also misidentified the person who prompted Teehee to decide to go to Washington; it was a tribe staffer.