For the first time, data show what disability rights advocates have known for some time: Autism is impacting non-White people, women and girls more than ever. And having the data available is fueling their calls for change.

In 2020, 1 in 36 children aged 8, or about 4 percent of boys and 1 percent of girls, were estimated to have autism, the first time the prevalence for girls has exceeded 1 percent, according to data from the Autism Spectrum Diagnosis Disabilities Monitoring Network. Also for the first time, the prevalence of autism among White children was lower than among other racial and ethnic groups.

The network’s report calls the significant shift in prevalence a “continued change,” referencing the consistent increases reported in recent years that “highlights the need for enhanced infrastructure to provide equitable diagnostic, treatment, and support services for all children with [autism spectrum disorder].”

Health equity experts and advocates say that this data is no surprise, and in fact, for some — namely Black women and girls — the research is playing an overdue game of catch-up. They’re calling for more inclusive research, diagnostic tools that account for the different ways autism manifests according to race and gender, and more culturally relevant resources and support.

For Bria Herbert, after 19 years of never feeling like she belonged, always wondering why — and blaming herself — absolution came in the form of an autism diagnosis.

“It’s weird, but I felt … relieved,” Herbert said. “Getting the diagnosis was vindicating.”

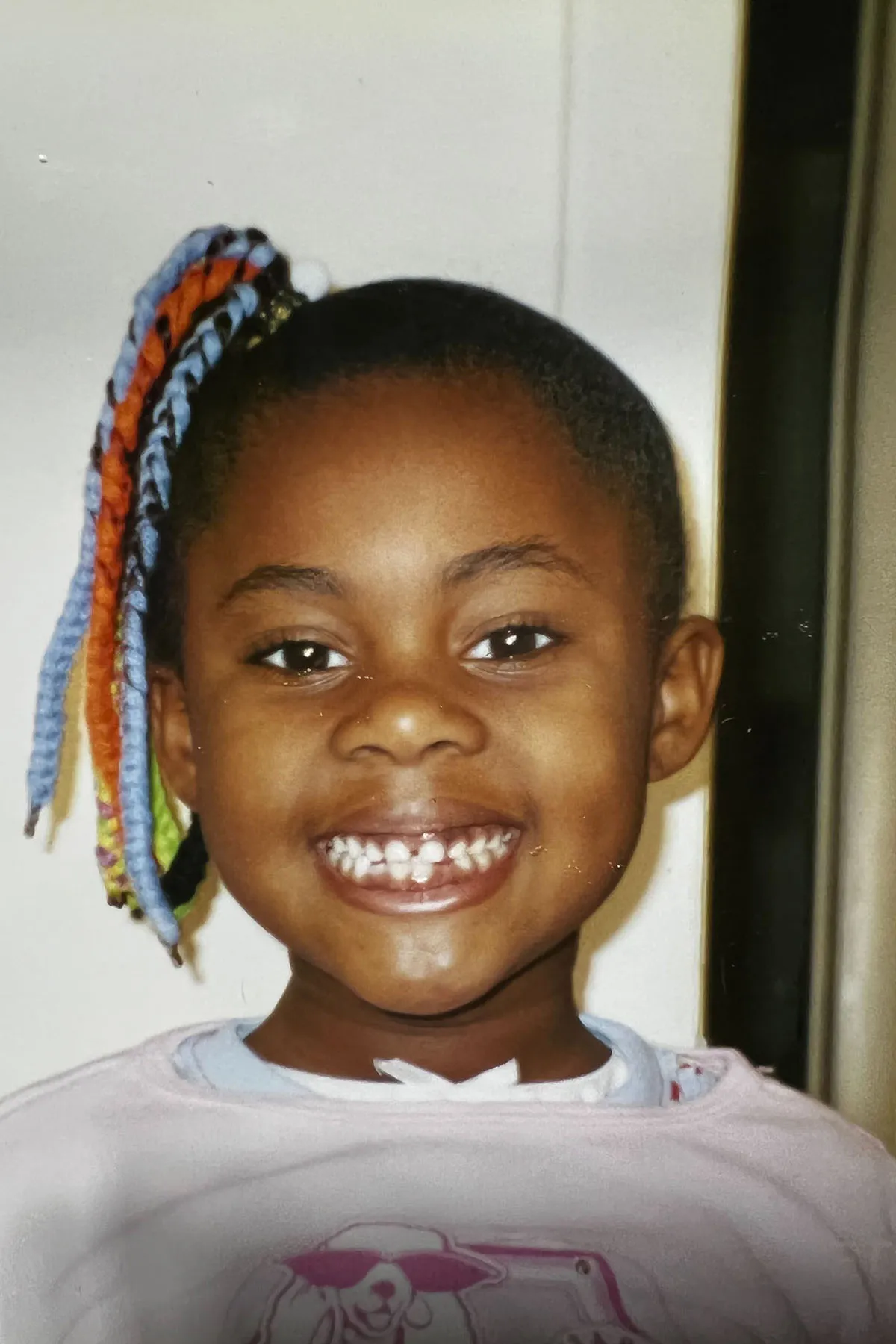

Being a Black girl and the eldest of four lent a uniquely weighted mantle to Herbert growing up, including more responsibility, higher standards and expectations of success. Academically, it was a rarity for Hubert to not excel. Outside of the classroom however, her childhood quietly told a different story. While nothing was wrong with her, something was different enough that it caught the attention of her peers and family.

“Other people definitely noticed, but just liked me anyway,” Herbert said, calling herself one of the lucky ones and thanking God she was a cute child.

“I used to do stuff like need to pull on people’s ears when I sucked my thumb to sleep. . . . I was weird, but I had the cuteness going for me. I got the adorable act down early so I didn’t have it that bad,”Herbert said, speaking to the social challenges, like bullying, that about 46 percent of autistic children face, according to a 2012 study in the Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine.

Instead of probing into why 7-year-old Bria was so “self-sufficient” that she could watch herself for hours at a time without needing to play or interact with anyone, or so “mature” that she could maintain her school and bedtime routine without prompting or distraction, the adults in Herbert’s life called her “responsible” and a “role model” for others.

Turning 18 meant a world of new for Herbert as she started her journey as an engineering and business double major at Florida A&M University. For the first time, the impact of her constant anxiety and feelings from having to navigate the world were too much for her therapist to explain away as “jitters” or for her to accept as normal. Hubert’s mom pushed her to go speak with someone, and she was finally diagnosed with autism.

“Autism and most mental health disorders present differently in Black women,” Herbert said. “Because autism is looked at through such a White and male lens, people don’t recognize similar behaviors with traditionally feminine or Black interests.”

Maire Diemer, a researcher, clinician and graduate student at the University of Missouri, agrees with Hubert’s assessment. Her work focuses on health equity within developmental disability study, particularly marginalized populations with autism.

In 2022 she published, “Autism presentation in female and Black populations: Examining the roles of identity, theory, and systemic inequalities,” a paper drawn from the trends among families she saw in clinic doing autism evaluations.

White parents seemed to be motivated to get their kids diagnosed as autistic or have a diagnosis of any kind using what Diemer referred to as “magic words” like “sensory processing issues” or “overwhelmed” when presenting their children’s cases. They used language that made it clear they were at the very least familiar with information on autism or developmental disabilities — and that would almost guarantee them a screening.

For families of color, however, she noticed the language used tended to consist of less clinical descriptors like “bad attitude,” “temper tantrums” or “busybody” to describe similar behavior.

Diemer said that while there are many factors that go into how a parent describes their children, more often than not it would result in non-White children being misdiagnosed or not flagged for further assessment.

“One example is with girls, oftentimes repetitive behaviors might be more gender stereotyped. So for example, one little girl I worked with repetitively drew animals,” Diemer said. “Like, draw a tiger. Turn the page. Draw a tiger. Turn the page. Draw a tiger. Turn the page. That is a classic repetitive behavior. But, it hadn’t been flagged for anybody because, ‘Little girls like to draw a lot of pictures.’”

“Instead of asking, ‘How is being a Black girl with autism different from being a White boy with autism?’ Let’s just talk about what being a Black girl with autism is like,” she said.

Dr. Temple Lovelace is program director of Assessment for Good, a program she founded to build equity in assessments to support Black and Latinx youth and their learning development. In response to the increase in diagnosis of ASD among Black children and girls, she conducted a review of the past 77 years of autism-related research and published her findings in 2021.

“In order to study Black autistic women and girls effectively, intersectionality demands the construction of a new analytical tool that addresses the interdependent, enmeshed nature of this new racialized, gendered, and abled identity,” Lovelace writes in her review.

One goal of her review, “Missing from the Narrative: A Seven Decade Scoping Review of the Inclusion of Black Autistic Women and Girls in Autism Research,” is “to accurately reflect the experiences of Black Autistic women and girls.”

Her research found that since 1943, only three studies featured Black girls. Of them, only one was explicitly studying a Black girl in America. Of the other two, one was conducted in South Africa and one didn’t report the location of the case study and resulted in the research team scouring secondary sources for complete information. All three were conducted over a 13-year-span (1993-2006), and none addressed intersectionality.

In the 77 years of autism-related research reviewed, only about 28 percent included race descriptors, and 46 percent considered race in determining the research outcomes. When race, ethnicity and nationality were recorded, 63.5 percent of participants identified as White, whereas 6.8 percent identified as Black.

“Black women and girls live as racialized beings. Their bodies are policed, their knowledge subjugated, and their health ignored,” Lovelace wrote. “The narratives that pathologize Black women and girls are rooted in a larger set of historical processes that have the predictive power to determine special education eligibility and post-secondary outcomes.”

Even with the billions of dollars the government has invested into autism-related research, there still is a lack of understanding and data on Black autistic women and girls.

Diemer said this is where advocacy can fill the hole that research hasn’t. She wrote in her article, “Female and Black populations in the United States are diagnosed later, are more likely to have an intellectual disability, and are excluded from research as well as services designed for autistic individuals.”

Lovelace and other experts attribute this exclusion to unique scrutiny and expectations placed on Black women and girls.

This rings true for Dr. Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, founder of Advocacy Without Borders.

“Sometimes people have these heartwarming stories about why they became an advocate. Like, something touched their heart. I wish I could say that was mine. Mine was anger,” Onaiwu said about her journey into her work and advocacy for Black women and girls.

Onaiwu has spoken at the White House and the United Nations about the need for investment into autism-related research and resources and has led research efforts at the National Institutes of Health and the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee within the Department of Health and Human Services.

Like Herbert, Onaiwu wasn’t diagnosed with autism until she was an adult, after years of unrecognized signs and behaviors.

As a researcher, Onaiwu said she can understand the medical conceptions and practices that didn’t even consider people who looked or behaved like her to be on the autism spectrum until the arrival of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fourth Edition in 1994.

Like many Black girls and women later diagnosed with autism, people recognized her traits and behavior as different — she was considered both “mature” and “young” for her age,” “overly clean and orderly” or, simply, “weird” — but no one attributed it to a disability. Now, she has had to unlearn the feelings of inadequacy and not belonging that were affirmed by bullying from her peers, authority figures and eventually even herself.

“I was hyperlexic —my parents weren’t worried about that. That was great. Yay, you could read at a young age? Wonderful. Black parents aren’t going to look down on that,” she said. “I could play by myself? Whereas a White person might be like,‘Oh they’re not social,’ my parents were relieved. They didn’t have time to entertain me every second of the day. . . . They saw it as a sign of maturity. I could do things like pick up patterns or routines? They thought that was orderly. What showed as my brain thinking in systems and patterns was, you know, seen as a positive thing.”

Onaiwu’s experience also highlights the risks that undiagnosed autism presents for children and young adults: She was suicidal by the time she was 11 years old and kept a journal of the thoughts that she couldn’t rid herself of. She smiled and nodded her way through her teens, by all appearances flourishing in school and meeting the expectations of a well-raised Black girl reared in the Midwest by immigrant parents, all the while suppressing her true self and being bullied and mistreated by those who saw through her efforts to mask her differences.

When Onaiwu’s daughter was 2 years old, others noticed similar patterns in their behaviors, like sensory processing and wanting to prevent her from growing into the 11-year-old that she once was, she made an appointment with her pediatrician. The visit led to an autism diagnosis for her daughter.

During the autism assessments, Onaiwu learned about early indicators of autism, including ordered play and hyperlexia, advanced reading skills and abilities in children that are unusual for a child’s age, and it resonated with her own experience as a child.

“Noting the similarities between us, my daughter’s providers suggested that I should consider testing,” Onaiwu said. It would take a year — and an autism diagnosis for her son — before she was assessed herself and had her diagnosis confirmed, at a price of about $4,000.

Many testing sites and resources for autism support are built for and focused on children and early intervention. In 1975 the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act laid the groundwork that now allows children who are three and under to receive interventions like speech and behavioral therapy for free.

In 2011, the National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center released a study citing the importance and impact of early interventions. Neural circuits, or connections, in a child’s brain are usually the most malleable in the first three years of life. While it’s never too late to support the needs of autistic children or adults, after those three years therapy and support can be more intensive — and challenging to find.

For autistic children this can mean that developmental “delays” aren’t something that they’ll just “grow out of” and certainly not in a timeline that’s conducive to expectations of them, in turn increasing the challenges faced across education, interpersonal relationships and self-worth. Subsequently the lack of awareness about behaviors that call for intervention, or information about how to find support, often leaves nontraditional patients, like adults, feeling aged out of resources.

While most insurance companies cover testing, early intervention and support for children, adults must pay thousands of dollars in assessment fees or spend years waiting for clinical trials and research waitlists that usually offer support at a discounted rate, rather than free. Although autism-related testing fees range from $500 to $5,000, many clinicians that offer assessment for adults are not covered by insurance.

“A girlfriend asked why I was sad and crying — I said, ‘These are tears of relief and joy.’ I spent much time blaming myself: Why couldn’t I get it together? Why was I broken? Alone with those thoughts. Yeah, they were definitely tears of joy,” Onaiwu said, recalling the day she got her diagnosis.

While the vindication from the diagnosis was freeing, Onaiwu said the absence of Black girls and women in autism research and discourse contributes to the alienation they experience and limits the options they have for community.

“That’s something that frustrates me sometimes about autism and not just communities, is because there’s this lip service about understanding intersectionality and hearing about it. But a lot of times it’s not truly integrated.”

Onaiwu doesn’t blame her parents for what they didn’t know. Now, along with creating resources for other Black girls, women and parents, one of her biggest goals is make sure her daughter never feels the way she spent 30 years of her life feeling.

“You know, in some ways I think it gave me my purpose — certainly contributed to who I am today — but I don’t want that for my daughter. I don’t want her to feel alone, you know? I don’t want that struggle to ever be a part of who she is. I don’t want that for anyone, that’s why I do this.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled the names of two sources.