Your trusted source for contextualizing the news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Minnesota’s House of Representatives passed a bill last month that would create an Office of Missing and Murdered African American Women to address disparities in missing persons cases. If the bill makes it through the Senate and is signed by the governor, it would create the first office of its kind focused on Black women in the nation.

The office stems from the findings of a 12-member task force, which was created through legislation by Democratic state Rep. Ruth Richardson to investigate the causes of violence against Black women and girls, and to report on measures that could be taken to reduce this violence.

A December 2022 report by the task force stated that despite Black women making up only 7 percent of the state’s population, they make up 40 percent of domestic violence victims. Experts say domestic violence, human trafficking and systemic poverty are all factors contributing to missing persons cases.

Black women are also three times more likely to be murdered than White women in Minnesota. Following the task force’s findings, Richardson introduced a bill to create the office, which she hopes will provide a framework for legislators across the country to address this crisis nationwide.

“I think that the blueprints that we have, including the report with the recommendations, and with this office as well, it gives us the opportunity to encourage other states to act and also the nation,” Richardson told The 19th.

-

Read Next:

Not only are Black women and girls disproportionately likely to be harmed, when they are, their cases are largely met with silence from law enforcement and media outlets. Nationally, cases involving Black girls and women remain open longer, experts said. An audit of missing persons data in Chicago showed that missing Black people appeared among the older cases in their database four times as much as White or Hispanic people.

According to National Crime Information Center statistics, 268,884 women in the country were reported missing in 2020. Nearly 100,000 of those were Black. While Black people account for less than 14 percent of the U.S. population, Black women made up more than one-third of all missing women reported in 2020.

With a $1.24 million annual allocation, the office would offer assistance with cold cases and provide grants to community organizations to ensure prevention programs are in place for issues including domestic violence and human trafficking, which often contribute to the reasons women go missing. It would also engage in public awareness campaigns, operate a missing persons alert system and issue further recommendations in addition to those provided by the task force.

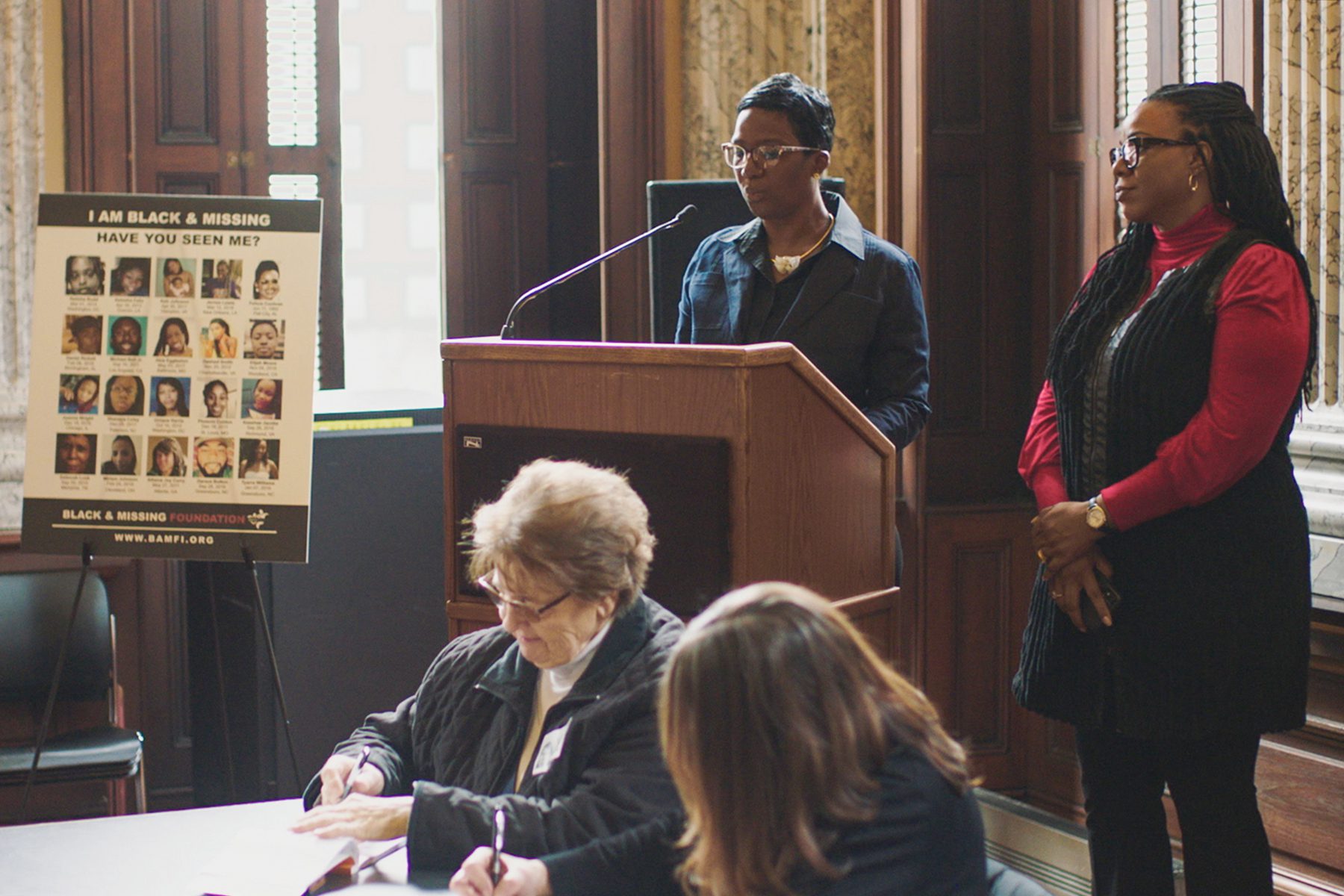

“What has occurred in Minnesota is historic,” said Derrica Wilson, co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation. Wilson, a former police officer, teamed up with her sister-in-law, a public relations expert, to found the group to bring awareness to missing persons of color. Together, she said, they have reunited or brought answers to more than 400 families.

“I think that [Richardson] has laid out the blueprint that other states across this country can adopt to protect our Black women and our Black girls because they are not protected. The resources are not allocated in the same manner,” Wilson said.

Richardson’s legislation is years in the making. She first introduced the idea of a task force in 2019, but it gained little traction. Then, the murder of George Floyd in her state in 2020 created a watershed moment for acknowledgment of racial injustice against Black people.

“The really sad reality of this is that it took another person dying and being murdered in order to get some traction for this to finally get heard and to put us in a space to be able to create the task force,” Richardson said.

She passed a resolution that year declaring racism a public health crisis, setting the stage to reintroduce legislation for Black women and girls. This time around, the task force legislation passed with bipartisan support.

Democrats currently have a trifecta in Minnesota, controlling the governor’s office and both chambers of the legislature.

Task force co-chair Lakeisha Lee is one of several family members of women who have fallen victim to this crisis. She and others have been recounting some of the worst moments of their lives to legislators for years, hoping for a change.

Lee’s 18-year-old sister Brittany Clardy went missing in 2013. When her family went to the police, Lee said they were told that 18-year-olds go missing all the time and that she had probably just run away. Clardy was later found murdered.

Situations like Clardy’s are all too common. Wilson said that people of color who go missing are often labeled runaways, which does not trigger an AMBER Alert. These alerts were developed in 1996 to provide early warnings of disappearances after the abduction and murder of a 9-year-old White girl named Amber Hagerman. Fewer police resources are dedicated, and there is no urgency in finding a runaway, according to Wilson. She said she noticed this while working as a law enforcement officer.

“You have to see that law enforcement doesn’t really view our community the same,” she said. “It appears that White women and girls are always viewed as the victims. And there’s this perception that when it’s a Black woman or a Black girl, they’re promiscuous or they’re fast, and that is so far from the truth.”

Both Richardson and Wilson mentioned how the crisis is a direct result of the lack of value placed on the lives of Black women and girls in this country.

In a 2014 report by the Urban Institute, people who self-identified as pimps stated that they believed the race of women they were trafficking played a factor in the likelihood of their arrests and the lengths of their sentences.

“They were only White females that I was charged with because that’s all they care about. If these females weren’t White I wouldn’t be facing all this time right now,” one interviewee said.

Another noted the disparity between his sentencing and that of his friend, who was caught at the same time for committing the same crime. The interviewee, who was trafficking a 15-year-old Black girl, was sentenced to three years in prison. His friend, who was trafficking a White girl, was sentenced to 15 years to life.

Along with law enforcement, mainstream media outlets are complicit in this crisis, advocates say. Late PBS anchor Gwen Ifill famously called this phenomenon “missing White woman syndrome.” White women and girls who go missing can be seen in the media on an endless loop, while Black women and girls rarely get that type of attention.

The Columbia Journalism Review released an analysis last year of media coverage of missing people, finding that young White women who are residents of big cities receive vastly disproportionate amounts of attention.

“We’re not asking to get something more than any other community,” Richardson said. “We’re asking for the same attention. We’re asking for the same coverage. We’re asking for the ability to have our lives honored in the same ways, and just reiterating that we are also worthy of protection.”