We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

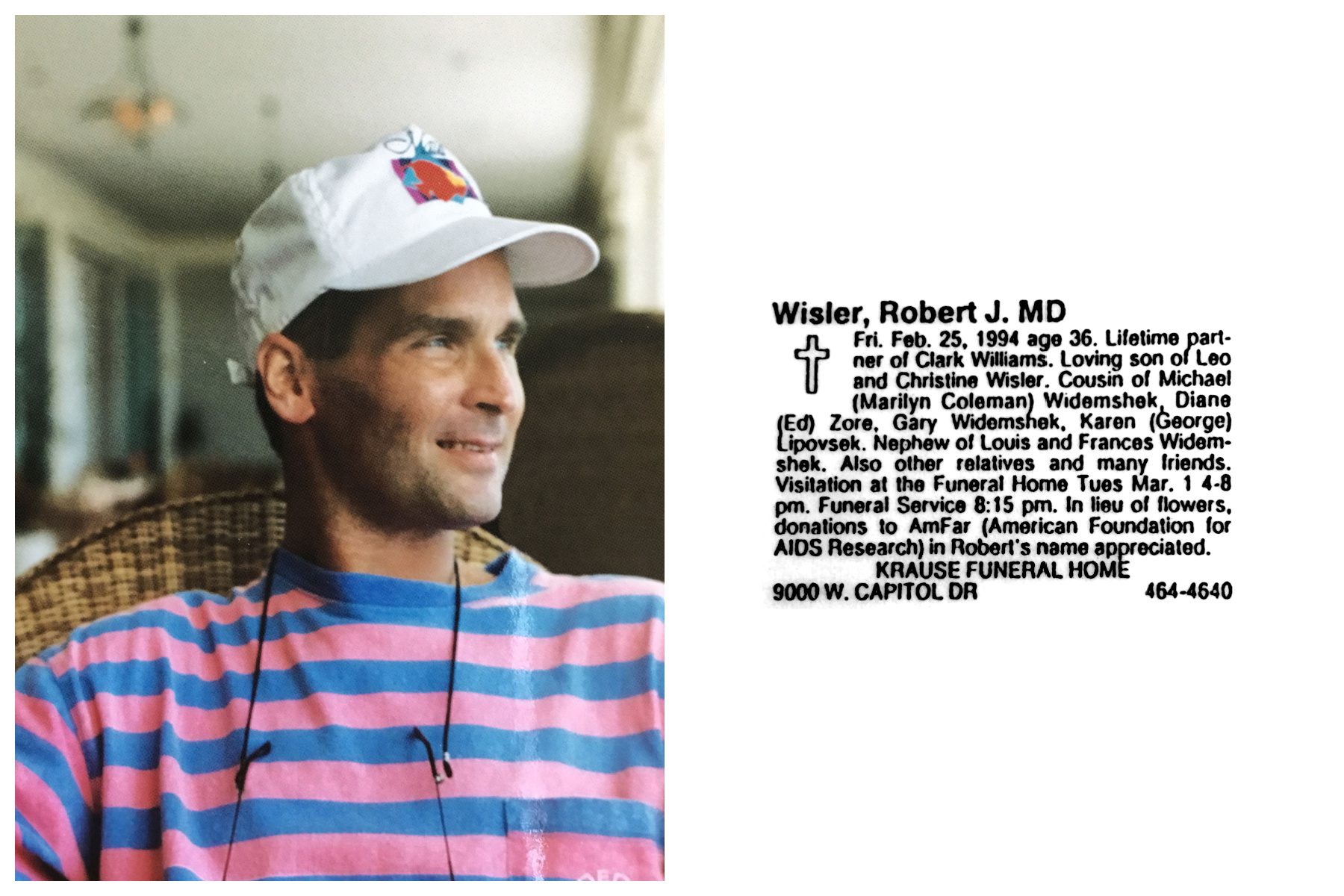

Clark Williams lost his first love, Robert Wisler, in 1994 to AIDS. Wisler died in his arms, and like so many other gay men, he died before the most effective treatments to control the virus destroying his immune system were available — after political indifference stifled early medical efforts.

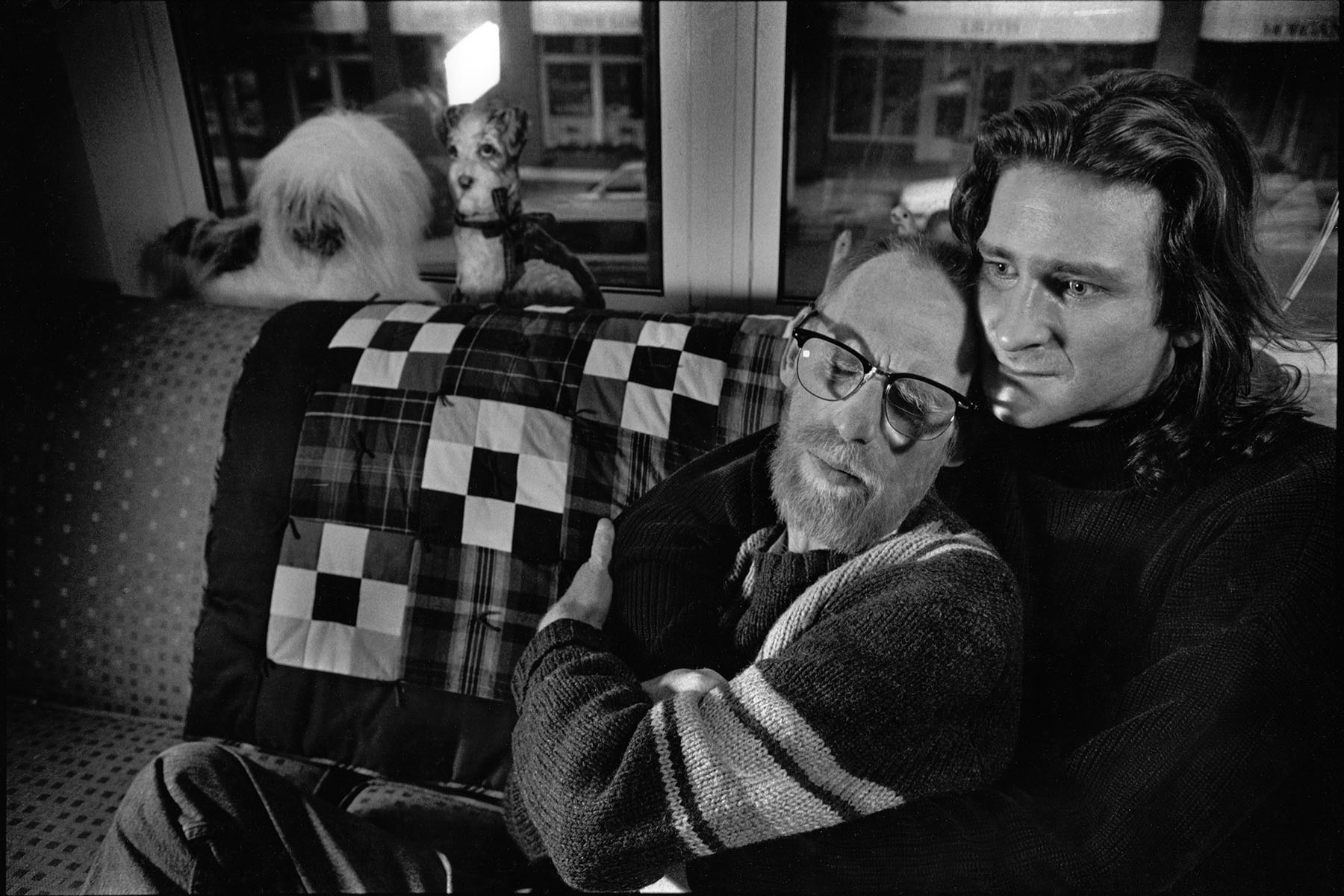

As Wisler died, the couple were together in his hospital bed, at home, finding refuge with the doors locked to the outside world. Five days before, Wisler had chosen to stop taking treatments that were wrecking his body. Williams knew the decision was an act of love to preserve what time they had left.

“Those last few days were the most beautiful times of our relationship. It was a snowy winter in Milwaukee. Snow was falling, we were isolated in the house,” he said. A home health nurse visited at night. After years of fighting, the end fell on them slowly, with the February snow, and Williams knew there was nowhere else in the world he would rather be. “I just held him, the entire time, for days. I just held him as he continued to weaken.”

Williams was stunned when he saw those final moments with the man he knew to be his husband — and echoes of the life they had built together in a world hostile to those with HIV and AIDS — mirrored, almost 30 years later, in “The Last of Us,” an HBO series chronicling a fungus-driven zombie apocalypse. He watched as two men living through a deadly pandemic decided to trust and love each other in spite of how easily it could all be taken away from them. He watched as they exchanged rings and vows in a world that couldn’t legally recognize their marriage.

“As I’m watching it, I’m like, ‘Oh my god,’ [‘The Last of Us’ co-showrunner] Craig Mazin wrote this piece that just made me feel like someone saw me and Robert,” he said. “Somehow Mazin wrote this piece of art that reflected not just the life that Robert and I had, a falling in love in this dystopian time, but the lives of so many of my friends who also found loves that they loved and lost.”

Bill and Frank’s decades-long relationship depicted in HBO’s “The Last of Us” was an unexpected departure from the award-winning video game that inspired the series. In the game, released in 2013, Frank is not even a living character — and he expresses contempt for Bill before dying. Their reimagined story resonated strongly with many LGBTQ+ viewers as a heartfelt homage to queer love found late in life, and in times of uncertainty.

It also struck a chord with some of those who lived through the spread of HIV and AIDS in the 1980s and 90s. Peter Staley, one of the country’s most prominent AIDS activists of that time, called the episode’s metaphor “a gift,” saying that “tears flowed remembering the tender love and bravery gay men summoned when facing death during the plague years” as he watched.

Perry Halkitis, dean of the Rutgers School of Public Health, lived and mourned through those years too. He lost his partner, the Village Voice editor Robert Massa, to complications caused by AIDS at St. Vincent’s hospital in New York City. Halkitis was holding him in his arms as they went to sleep. On that Saturday morning in 1994, Massa woke up and died in his arms.

The relationship between Bill and Frank didn’t resonate with him as a metaphor for those with HIV or AIDs — and Halkitis has spent time documenting the lived experiences of other HIV-positive gay men who survived that era. However, he did find meaning in Bill realizing his own identity once he found the right person. Many men today suppress their sexuality, he said, but still have the ability to love and discover who they really are.

“When he met Frank, he became his authentic self and his life had meaning. And then because his life had meaning, he was afraid to die,” he said.

Williams watched as the character Bill became a caretaker for his partner, Frank — helping him get out of bed, cutting up his food, picking out his pills. He recalled the struggle and profound intimacy of taking care of Wisler as they both did whatever they could to keep him alive. But ultimately, they didn’t have enough time. The fight was taking a physical toll on both of them. Wisler’s health was declining. He chose to let his life end prematurely without the stress of constantly trying to fight what they both knew had become inevitable.

In the latest episode of “The Last of Us,” which aired Sunday, Williams watched as Frank made a similar decision: to end his life. His symptoms from an unspecified degenerative neuromuscular disorder, either multiple sclerosis or early ALS, had left him unable to move, paint, or live how he wanted to live. “Then you will take me by my hand … bring me to our bed … and I will fall asleep in your arms,” Frank tells Bill ahead of time, while asking for his help to have “one more good day.”

Williams remembers his husband’s last moments alive as an unexplained burst of energy, a vital insistence that seemed like he had something to share, if only he could get the words out. He sat up suddenly and yelled “Clark!” several times — not in pain, but as if in amazement.

“Whatever it was, it was remarkable and he wanted to share it with me. And that’s when he cast his last breath, was with me holding him and him trying to share something with me. It’s a mystery. I hope one day I’ll find out what it was.”

In “The Last of Us,” Bill ends his life alongside Frank, as the two retreat into their bedroom and lock the door to the outside world. Williams recognized that urge to follow a deceased loved one. After his husband died, he had moments where he wanted to end his own life. He felt broken — like he had given everything.

“I didn’t want to face a world without the person I loved the most,” he said. Moving through his grief was messy, confusing and lonely. His father, the first person he came out to, stayed with him in the weeks after Wisler’s death, standing as a witness to his grief and to how much he loved his partner. It took time to put the painful experience in context.

“He did not want to see me end my life. He fought too hard to live for me to end my life,” Williams said. “So I had to figure it out. I had to figure out what my life was going to look like without him. And to allow myself to change.”

Williams has built that new life, the one he believes that Wisler wanted for him, with his husband Jim Moore and his daughter Caroline. And yet, when he watched Bill and Frank retreat into their bedroom to share their last moments together — a private scene that no viewers, or any other characters in the show, are welcome to join — he felt seen.

“I’m glad they didn’t show the end of their lives. … There was no need to. It is so intimate. I guess because I’ve been in that room, I understand what that’s like,” Williams said.

Matthew Rose, who has worked as a health equity and HIV patient advocate for over a decade, felt that the “Last of Us” episode offered a clear depiction of committing to love in the face of death and portrayed a level of queer intimacy not often seen on screen. It laid bare Bill’s awkwardness and tentative vulnerability in expressing feelings for another man seemingly for the first time. As Bill’s partner, Frank, breathed new life into their post-apocalyptic surroundings by sprucing up their barren town and planting strawberries, those small touches became symbols of hope and faith in their relationship that transcended their bleak circumstances.

That such a relationship was between two older men is an important representation of enduring love, or finding love at an older age, Rose said. Depicting that kind of love — wherein two middle-aged gay men find happiness growing old together — was also vital to the showrunners, as Mazin explained on the official companion podcast for “The Last of Us.”

There are many untold stories of those who lived with HIV and AIDS, Williams said. That’s why he believes seeing a love story between two older gay men being told on “The Last of Us” was surprising and compelling for so many.

“To have it be told in such an honest way, that really reflected the dignity of so many of the people I knew who were finding each other during a time of chaos, that’s why it resonated so much with me. The years of the HIV, AIDS pandemic felt dystopian. There was death all around us. There were threats all around us. And yet we were all trying to survive in our own way and trying to find love in our way. And I’m an example of that.”

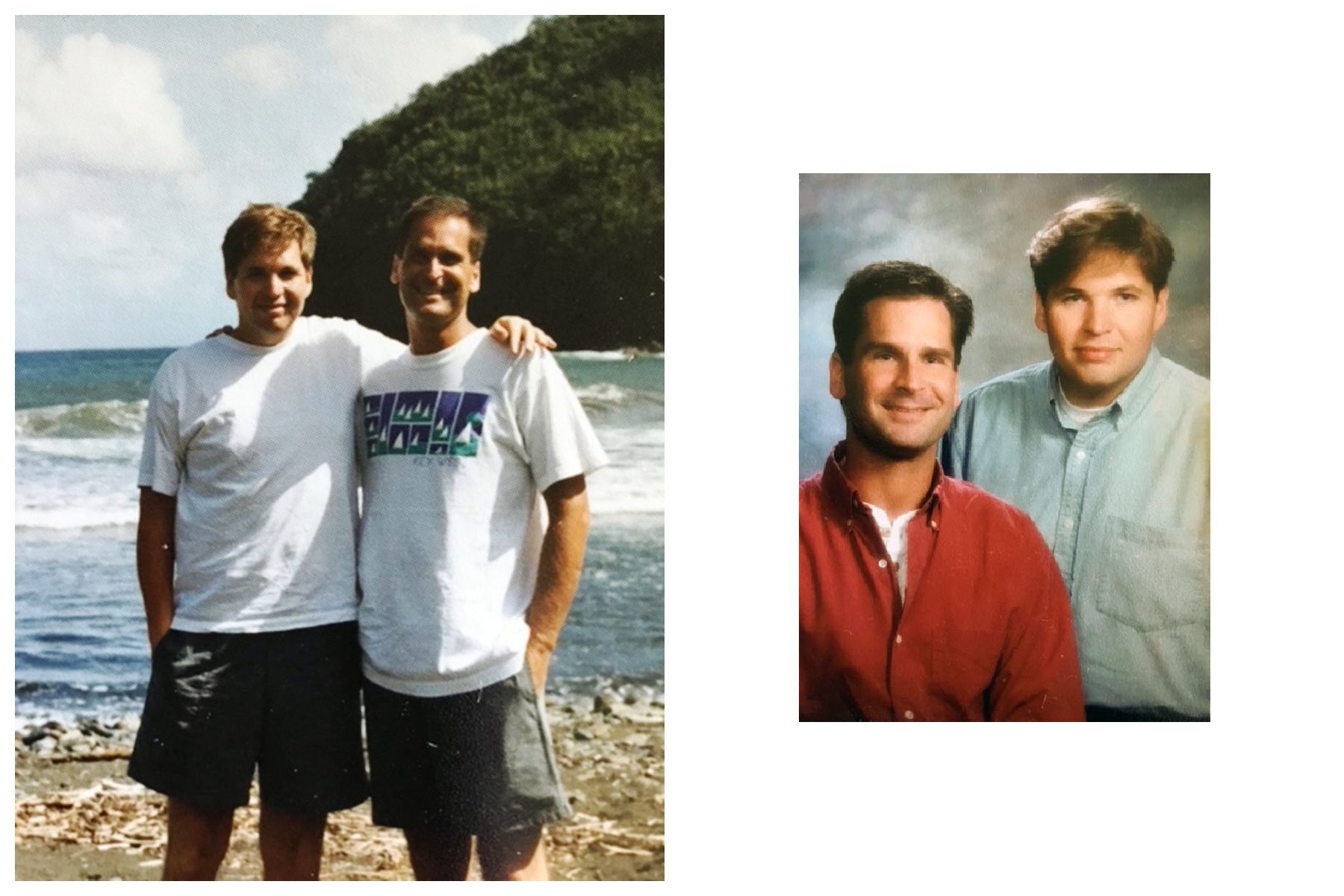

Williams met Wisler, a “brutally handsome” doctor who had just finished his residency, in Milwaukee in 1990. Because of where they lived, and the times they lived in, coming out as gay or admitting to being HIV-positive meant taking on real risk. Wisler was terrified to share his status; he didn’t disclose it to Williams for a couple weeks after they met. As more time passed, Williams learned that Wisler had received an AIDS diagnosis – his symptoms were worsening. Both of their lives were upended. Williams lost his job after his employer learned of his personal circumstances. After paying out of pocket for the mounting costs of treatments, Wisler eventually used his insurance — which meant his job found out about his condition. He was asked to resign.

They exchanged rings and vows in 1992 — becoming married, although in the eyes of the government, they were little more than roommates — while on vacation in Hawaii.

The stigma that Williams and Wisler experienced was common for many queer men in the early 1990s, experts say — and it was coupled with a lack of comprehensive medical care and slow-moving federal funding to support that care.

“In those early days, before a combination therapy hit, you were waiting to die,” Rose said. Even in the early 1990s, a lack of real treatment options prompted difficult decisions about how to die with dignity, once someone’s quality of life had deteriorated, he said. The initial AZT treatment was toxic and full of side effects. Early on, so-called treatments managed pain, but didn’t offer much more than that, said Lindsey Dawson, director for LGBTQ health policy and associate director for HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The early federal response lagged as the Reagan administration failed to acknowledge the spread of HIV. Change was driven by activists who pushed the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to accelerate approval pathways for treatment and who pushed the National Institute of Health to conduct more research into the virus, Dawson said. It took until the mid-1990s for real federal funding to be brought to the fight, especially through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Breakthroughs came with the first FDA-approved protease inhibitor in 1995 and the use of combination therapy as a new standard of care.

Williams was thrilled that these pivotal advancements were healing his friends. It was also gut-wrenching that they came just a few years too late to save Wisler’s life. Halkitis remembers thinking, if only his own partner could have held on for just a bit longer — and what a difference that would have made for everyone else who was playing the same waiting game.

Current treatments now stave off the progression of HIV, preventing or delaying the more advanced stages that invite opportunistic infections, like those that killed Williams’ partner. The understanding that “undetectable = untransmittable” also marks a key turning point in society’s relationship to the virus as a mangeable one.

Although there’s been progress among society’s emotional response to the virus, Halkitis sees regression in state-level policy. Tennessee recently rejected federal funding to combat HIV, and a federal judge in Texas last year ruled that a Christian-owned company does not have to cover preventative HIV drugs under the Affordable Care Act. That ruling sets a scary precedent that could allow employers to discriminate against people who are HIV positive, he said.

When Williams thinks back to meeting Wisler, to making the easy decision to build a relationship with him despite the struggles ahead, he reflects that he was too young to know what the power of grief would do to him. He was in his 20s. He didn’t think Wisler would die — he did everything he could to prevent it. Letting him die equaled failure.

“We all fought really fucking hard in order to live. So there’s no glory in death. I wish death hadn’t come. I’ve got enough rage for the way our government responded in the early days of the epidemic. That many people didn’t have to die,” he said. “There’s no beauty in that. It didn’t have to happen.”

Choosing to move forward, to accept love despite the odds, is part of what made Bill and Frank seem familiar to him.

“Bill had a million reasons not to let Frank inside those gates. You know, a lot of very good reasons. And the same with Frank. He had a ton of reasons to leave,” Clark said. “But they allowed their human nature to love, to find each other, through all of that. And that’s how I think Robert and I ended up finding our love … until death do us part.”