For more than two decades, Humaira Abid has used her art to explore taboos, defy gender stereotypes, and educate the public about women refugees and social injustice. She was born and raised in Pakistan but is now based in Seattle, and her work primarily focuses on the challenges that women in South Asia and the Middle East face. She uses miniature paintings and wood carvings, both male-dominated mediums, to highlight issues such as reproductive health, political instability, discrimination and abuse.

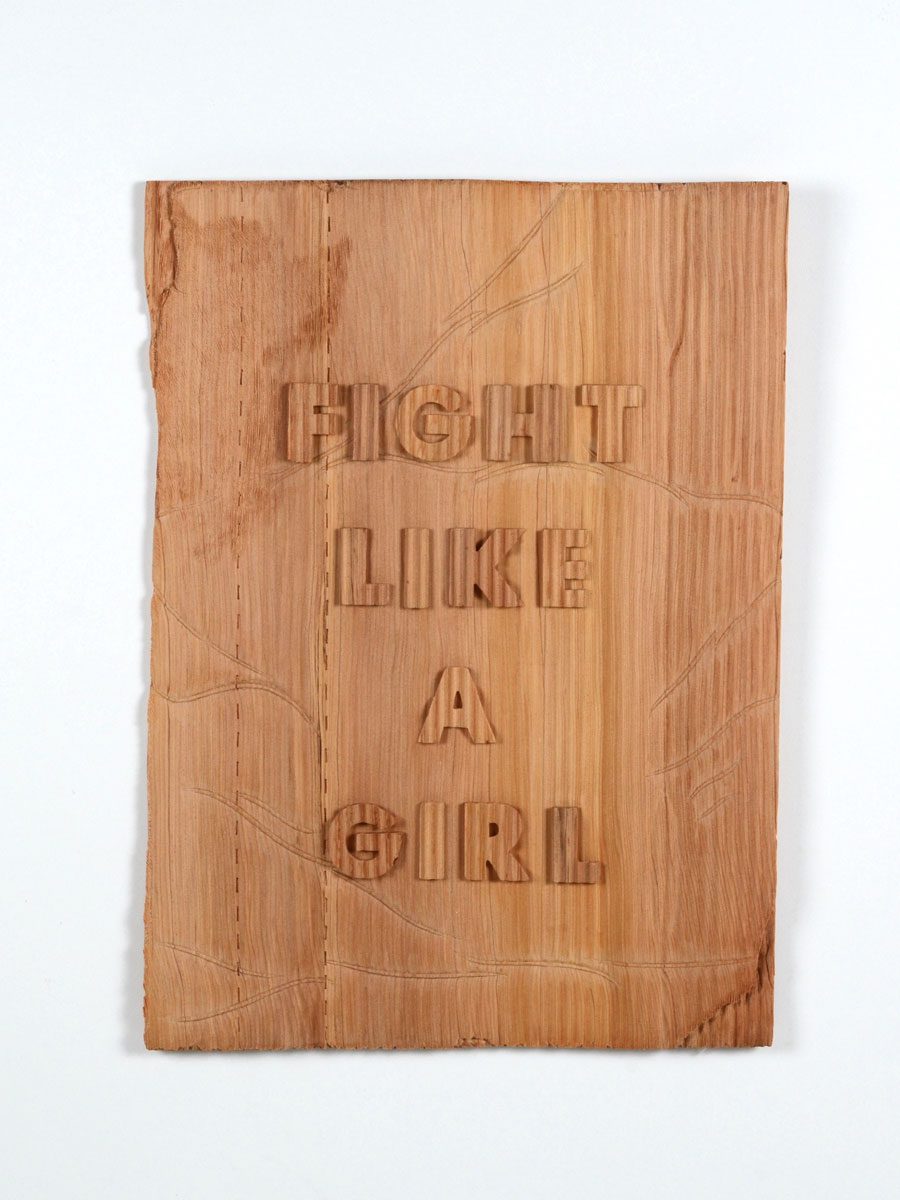

With pine-carved protest signs against rape and racism and a mixed-media work about the Afghan girls and women denied schooling, Abid’s latest collection touches on themes pertinent to recent women’s rights demonstrations for education in Afghanistan and against the government in Iran. Called “Fight Like a Girl,” the exhibition was on display at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle through October.

Her art has referenced Saudi Arabia’s ban on women motorists, which was reversed in 2018, and a lesser-known law there barring women from using eye makeup or having “tempting eyes.” In 2021, an Abid work addressing both restrictions appeared on a Los Angeles billboard as part of an outdoor art exhibition. It shows a woman’s reflection in a rearview mirror. Since she’s wearing a niqab, her eyes are her only observable facial feature, but one eye stands out because of the bruise covering it.

Starting in April, Abid’s traveling show “Searching for Home” will be on display at the Museum of Art and Culture in Spokane, Washington. The exhibit explores the global refugee crisis, particularly its impact on women and girls. For this collection, Abid spent months interviewing refugee women from countries including Somalia, Syria and Afghanistan.

The 19th spoke with Abid about how she confronts gender and justice in her art and how her work intersects with global women’s political causes.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Nadra Nittle: You have spent your career challenging gender stereotypes, especially of women in largely Muslim regions. Given this, what are your thoughts about the images of women in Iran defying the Islamic regime and fighting for their freedom?

Humaira Abid: First of all, thank you for thinking of my work and also including my voice. And, yes, you’re right; a lot of my work is about women’s issues and Muslim women and societies where there are a lot of boundaries and restrictions imposed on them. Iran has always been on my mind, especially for this issue of hijab and covering head imposed on women. I always believe that it should be a choice, and women should have the freedom to choose, not just about the hijab but anything related to their body and their life.

What can you tell me about your latest exhibit, “Fight Like a Girl?” Do you see any correlation between the exhibit and what’s happening currently in the world?

This phrase “fight like a girl” has been interpreted differently in the past. It was used as a put-down if a boy didn’t show enough strength. He would be told, “Oh, you’re acting like a girl. You’re not throwing the ball strong enough.” But, actually, “fight like a girl” is much more than that. We fight for our rights from the day we are born just to speak up and live our life the way we want to and do things we want to pursue in life. There are so many boundaries imposed on us. Being a Muslim woman, I always question why is it that when people start paying more attention to religion, they suddenly think of imposing boundaries on women. I question all of this, and “fight like a girl” for me means fighting for equality, fighting for equal rights, fighting just to live your life the way you want to live.

I recently interviewed a woman who lives in the United States but was born in Iran. She said some of the images of Iranian women protesting shock her because the women are putting their lives on the line with their acts of resistance. What do you think about the images you’ve seen?

They show the strength of women. One of the images that stood out to me was a woman cutting her hair, and I was like, “Oh my gosh, what if I can use that in my work as a way to talk about all these issues?” The images are very, very powerful. In order to move toward the change we want to see in the world, we need to participate in that fight. I have by carving some protest signs in wood that look like the cardboard signs carried in women’s marches around the world.

Can you discuss why sculpting in wood appeals to you?

I do it because it’s a male-dominated medium and what better medium to talk about women’s issues? When I was in art school, I started getting warnings not to take sculpture as my major because it’s considered physically challenging, along with other challenges like, in a Muslim society, doing three-dimensional art is considered going against Islam. And, yes, it is challenging, but there is a lack of women’s voices in that medium. I felt the need to bring a woman’s voice to that medium, and my other medium, miniature painting, is also historically male dominated. So, I intentionally chose those mediums that are historically male-dominated.

What has the reaction been to your art, especially as censorship is on the rise throughout the United States?

I am not aware of the censorship issue in the U.S., but I do feel it in many other regions, especially in Muslim countries. I’m a little bit surprised about censorship rising in the U.S. because America talks and pays so much attention to freedom of speech. But I agree that … people are finding it difficult to talk about these issues.

As an artist, I don’t think I pay enough attention to censorship because it is not something I believe in personally. Even when I was living in Pakistan, I was painting nudes. But one of my sisters lives in Dubai, and she started telling me that for painting “Tempting Eyes” and talking about issues in Saudi Arabia, I can get in trouble. But I try not to pay attention to that and not let anything stop me from talking about these issues because almost all of my work is about stereotypes and taboos related to women in the world.

Do you think there’s enough awareness in the United States about the issues women across the globe are facing?

We are living at this time where nothing is segregated or isolated, and every situation and region affects other regions. For example, whenever there are boundaries imposed on women in one Muslim country, other countries strive to follow them. So, all of us, no matter where we are living, are affected by it. I feel because this country [the United States] has so much power there is not enough focus on these issues. You probably are aware of my piece, “Tempting Eyes,” which went on a billboard and was about a driving ban on women and the tempting eyes law in Saudi Arabia. Many people knew about the driving ban, but the majority didn’t know about the tempting eyes law, which was made under the religious morality police. Again, the same thing is happening in Iran with the issue of hijab under the morality police.

How do you think art can be used to educate people about global events they may not understand?

This is something I pay a lot of attention to since I feel art has an advantage. Through aesthetics and beauty, it can bring people closer and then open up all these difficult topics. Both of my mediums have this aesthetic value to it. I also pay attention to detail because some of my topics — puberty, sex, menstrual cycles, relationship issues, fertility issues — are so heavy and taboo that some people find them difficult to talk about. When people come closer to my art, they say, “Oh my gosh. What is this piece really talking about?” And then it makes them think and open up all these different layers. I also feel sharing experiences and stories are important because when one person shares their story, it gives courage to other people to share their stories as well. And sharing is a step toward discussing the issue and hopefully toward resolution and change.