Flu case counts are at their highest level for early December in a decade. COVID-19 is spiking once again. Surging diagnoses of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are resulting in overcrowded pediatric emergency rooms.

And still, research shows, teachers may not be staying home when they’re sick.

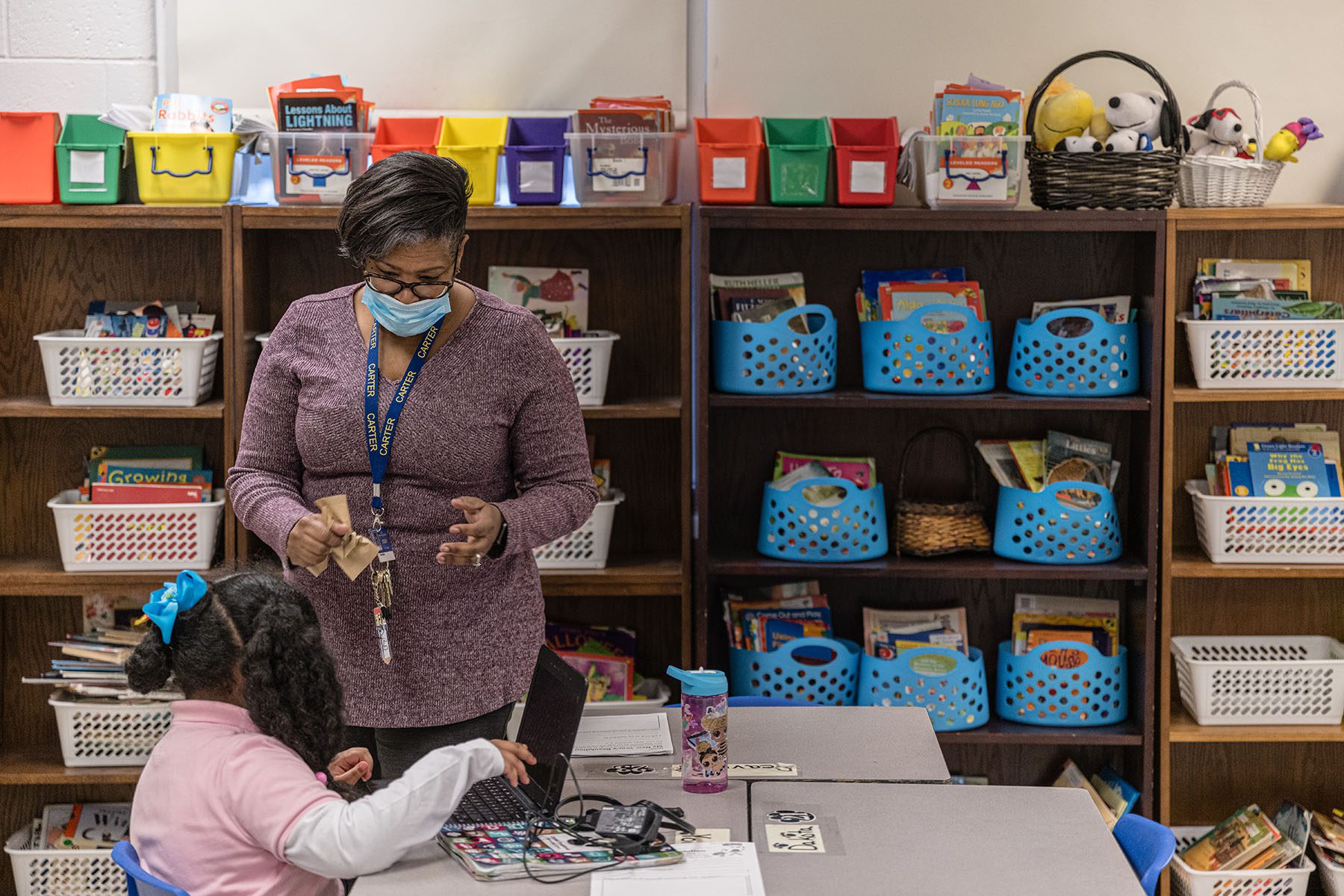

With public health experts worried about a brutal winter of sickness, elementary schools in particular — which are notorious hotbeds of germs — are being stretched thin. Waves of infection are forcing some districts to temporarily adopt remote learning until enough students and teachers are well enough to return to the classroom. The COVID-specific extra sick leave many teachers received at the height of the pandemic is no longer available in many places.

But survey data shared with The 19th from the Education Week Research Center, which studies national education policy, shows that even with viruses spreading through the classroom, teachers — and particularly elementary school teachers — are largely coming into work even when ill. Many say staying out of the classroom is just too difficult.

“There’s a lot of virus circulating, and therefore there’s going to be more people at risk,” said Jennifer Kates, a senior vice president and global health expert at the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. “Removing yourself from the situation is really important from a public health perspective — we know that and we know that more than we ever have. What’s challenging is there’s a lot of real and perceived barriers to doing that.”

Teachers, who are mostly women, are more likely than the general population to have paid sick leave benefits. But, the data suggests, that isn’t sufficient on its own.

“I try not to use sick days unless I’m on my deathbed,” wrote an elementary school teacher from Wisconsin, according to the survey responses. “It is more work to be out than to be at school. Plus I get pulled to fill in when others are out sick.”

“I try to avoid taking the day off, unless it’s COVID-19 or I’m really sick and unable to move because I don’t want my students to get out of routines at school,” wrote another elementary school teacher in Texas who works in special education.

“We don’t have money for subs, so teachers come in even when they’re sick,” wrote an elementary teacher from Washington.

And from an elementary school teacher in New Mexico: “I always hate taking sick days because it takes too much work to be out.”

Across grade levels, only 1 in 4 teachers reported taking a sick day if they felt ill, per the national survey conducted in late October and early November by the Education Week Research Center. Meanwhile, 35 percent of teachers said they try to avoid taking a day off unless they have COVID-19 or “can’t get out of bed.” And elementary school teachers were even less likely to stay home, per the data. About 49 percent said they avoided taking a sick day unless absolutely necessary.

The data isn’t surprising, said Holly Kurtz, who directs the Education Week Research Center. People were generally encouraged to stay home if they tested positive for COVID-19. But that message doesn’t appear to have been repurposed to address how people navigate other viral infections such as the flu or RSV.

Meanwhile, the pressures on teachers remain acute. Substitute teachers have been in short supply for years, a concern amplified by the pandemic. And full-time teachers, burned out from teaching through the health crisis, have quit in increasing numbers. With elementary school in particular, students are often too young to work without active instructor supervision.

“Even if they have paid sick leave, [teachers] worry about students falling behind and worry about burdening their colleagues,” Kurtz said.

The implications are significant not only for teachers, but also parents, noted Kates, who has an elementary school-aged son. If school employees aren’t able to use their sick leave, it increases the likelihood that viruses spread further. If her son falls sick at school, she can work from home and take care of him. But, she added, not all parents have that same flexibility.

“This is a challenge that as a society we haven’t figured out,” she said.

Rachel Thomas, a middle school English teacher in Washington, D.C., hasn’t fallen ill yet this year. Since noticing her colleagues get sick, and more students staying home with illnesses, she’s resumed wearing a mask inside her school building, an older facility where she worries about the ventilation.

If she does fall ill, she said, she would stay home from work until feeling better, an approach that her school’s leaders encourage. But she recalled working in other schools where, even if teachers had paid sick leave, they were generally likely to come into work anyway.

“That’s a culture in education, because we do understand there’s limited substitutes,” she said. ”You just have to tough it out.”