President Joe Biden’s judicial appointees stand out from his predecessors’ in their diversity, an achievement toward the administration’s goal to better reflect the nation in all three branches of the government.

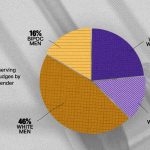

About 74 percent of the president’s 95 confirmed nominees to federal courts are women, and about 46 percent are women of color, more than for any other president. Democrats have also confirmed nine Black women to serve as appellate judges, more than doubling the previous total number of Black women to serve on the country’s second-highest courts. Most notably, Biden appointed Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman to join the U.S. Supreme Court.

As this year’s legislative session comes to an end, 46 nominees remain unconfirmed. Twenty-five are women — 18 of whom are women of color. Over the last several months progressive groups have called for Senate Democrats to speed up confirmations before the end of the year. However, with little time left in the legislative session and other priorities to handle, a number of Biden’s remaining nominations will likely expire, meaning that he will have to either renominate them or put forward new candidates.

The outcome of the midterm elections allowed Democrats to maintain a majority in the Senate, enabling them to continue shaping the courts for two more years. Despite this extended control, progressive groups told The 19th they view the years ahead as a push against Senate Republicans’ lasting long-term effect on the federal bench during former President Donald Trump’s administration.

“By the end of Trump’s term he had over 200 judicial nominees. And so we know that if we want to get to that number, we definitely have a long way to go,” said Kimberly Humphrey, legal director for federal courts at Alliance for Justice, a progressive judicial advocacy group.

Biden is outpacing Trump’s 85 judicial confirmations at this point in their respective terms. The Trump administration’s nominations and confirmations, however, accelerated in its last two years: By the end of four years, Trump reached a total of 234 confirmed judges. About 24 percent of them were women. By contrast, Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush each appointed close to 330 federal judges over eight years.

“President Trump set the record for the most circuit judges and most district judges from a single presidential term since 1980, and President Biden has the opportunity to match that with a particular focus on diversity in the courts: the most women, the most people of color, the most LGBTQ judges and the most that have come from professional backgrounds of representing individuals rather than corporations,” said Christopher Kang, cofounder and chief counsel of the judicial advocacy group Demand Justice.

In his first two years in office, Biden has prioritized nominating people from underrepresented backgrounds in terms of race, gender and professional experience. Rather than focusing on judicial candidates who have worked at private law firms, Biden has nominated the most people with backgrounds as public defenders. Humphrey commended this effort and noted that Biden could bring even more professional diversity to the federal bench by including more people who have worked in areas like labor law, climate justice and women’s rights.

Looking ahead to the next Congress, Democrats do not face any clear hurdles that could obstruct their efforts to confirm more judges.

On Friday, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona announced plans to break from the Democratic Party and become an Independent. Prior to Sinema’s announcement, Democrats had 51 senators with the re-election of Raphael Warnock in his runoff race on December 6. Extending their lead by even one seat would have given them some flexibility in the event of disagreement over a nominee or a senator’s potential absence during a vote.

Sinema has been a key and sometimes unpredictable vote in the evenly split Senate, giving her a lot of influence this session. But she has shown reliable support for Biden’s judicial nominees and will likely maintain a similar voting presence in the chamber even with the switch to Independent.

Though Biden will need to renominate nominees who are not confirmed this year, they are not necessarily required to go through confirmation hearings again. In fact, very little of the judicial confirmation process people have become familiar with is actually required by the Constitution, said Amy Steigerwalt, professor and associate chair of the political science department at Georgia State University. The Constitution states the president shall nominate and appoint people to courts with the “advice and consent of the Senate,” but does not dictate how that process should take place.

“The Senate has created its own internal process,” Steigerwalt said. “So if they want to say for all intents and purposes that, ‘We have already considered this nominee in committee and we see that as sufficient,’ they can do that.”

Progressives pushing for more diversity on the federal bench said that changing up some of the unofficial processes for judicial confirmations could expedite the Senate’s ability to move through nominees.

In a July article for Slate, Kang encouraged Senate Democrats to be more aggressive in their approach to the judicial confirmation process, including bypassing some Senate traditions that prolong the process. One example is that senators of the president’s party will recommend district court judges from their home state to the White House. But Democrats do not always meet the deadlines set for these recommendations, leaving the judicial vacancies unfilled for a longer period of time.

Another tradition is that any senator can essentially veto a federal judicial nominee from their home state. As a courtesy, if a nominee does not receive support from a senator in their home state, whether Republican or Democrat, that candidate may not advance in the Senate Judiciary Committee. The committee’s adherence to this has varied, depending on the chairman.

“I think this courtesy has to stop, and I think that this is going to be one of the big questions in terms of President Biden’s ability to really reshape the courts everywhere in the country, not just where there are Democratic senators,” Kang told The 19th.

Beyond looking to match Trump’s number of appointments, Humphrey and Kang expressed urgency about filling prolonged court vacancies, which slow down a particular court’s ability to move through cases. There are 83 vacancies currently across federal courts and 46 pending nominees, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

“That means that you’re not having our citizens get the justice that they need, because of backlogs in courthouses,” Humphrey said. “So I think that’s an important aspect of the push in making sure that we aren’t, you know, allowing things to flow the way that it should. And when we can be focused and keep these vacancies being filled as quickly as possible, then we’re helping all of our communities across the country.”