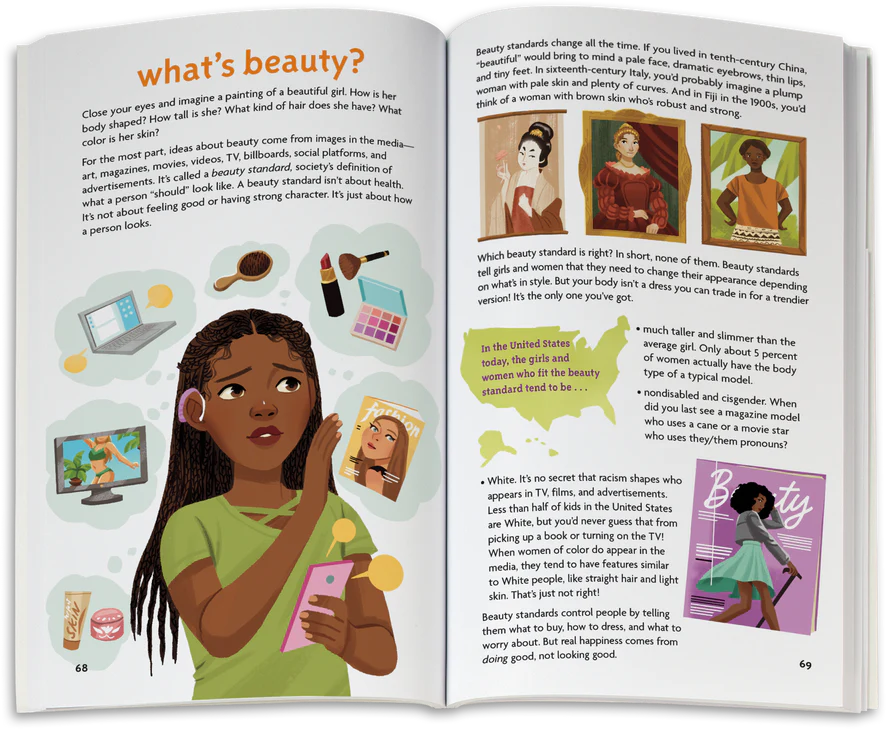

American Girl, best known for its historical dolls and their accompanying books and accessories, is making headlines on right-wing media this week. In addition to its dolls and their stories, the brand is well-known for their Smart Girl’s Guide book series, the latest of which is “Body Image: How to Love Yourself, Live Life to the Fullest, and Celebrate All Kinds of Bodies.” The book is facing intense backlash from right-wing outlets for its inclusion of a transgender Pride flag and mentions of they/them pronouns and gender-affirming care in its pages.

The section in question: two pages titled, “Gender Joy,” which starts by saying, “Messages about how bodies ‘should’ look are different depending on a person’s gender. … Luckily, it’s not your job to look the way people expect — it’s your job to be you.”

The book is the first from American Girl to explicitly address gender identity. In doing so, the company has unleashed a wave of criticism from conservative critics, who have seized on the book’s content to perpetuate the anti-LGBTQ+ rights talking point that support for trans young people is equivalent to forcing children to medically transition without their consent. Fox News commentator Kristi Hamrick said that the book sends the message to girls that, “they might not be good enough as they are” by including trans-inclusive content. Hamrick claimed that by “telling young girls that when they are uncomfortable, they should consider pursuing what can be unfixable changes to their bodies,” and suggested that the brand is pushing puberty blockers onto children.

Building off this, conservative commentators and social media influencers are calling for a ban on both the “Body Image” book and a boycott of the American Girl brand.

The current attacks on “Body Image” not only speak to the heightened state of targeted hate against queer and transgender individuals, but the unique position that the American Girl brand holds in American culture and the ways people look to it to define popular conceptions of the very idea of girlhood and gender norming.

American Girl built itself around themes like history, girlhood, initiative and innocence. The characters’ wholesome image — combined with expensive dolls that are designed and marketed as something to be explicitly cared for — means that the brand is also one that is “appreciated by more conservative families,” said Emilie Zaslow, a professor and chair of communication and media studies at Pace University and the author of “Playing with America’s Doll: A Cultural Analysis of the American Girl Collection.”

“People felt like they could trust American Girl and they still do,” Zaslow said. “The perception is that American Girl is going to protect girls and will provide them with safe stories about girlhood.”

Pleasant Rowland founded American Girl in the 1980s after trying to buy dolls for her nieces and being struck by the fact that the market was largely baby dolls and Barbies. “She didn’t want them to either be mothers and have baby dolls or play with Barbie and be introduced to ideas about adulthood too early,” Zaslow said.

The idea of girlhood itself was going through its own cultural revolution at that time, with Madonna topping the charts and the movie “Dirty Dancing” becoming a cultural phenomenon. “Conversations about teen girls and their sexuality were suddenly being brought into everyday life,” Zaslow said. As a result of this, she explained, a lot of second-wave feminists, a label with which Rowland identified, found themselves concerned by what they perceived as the continued objectification of women’s bodies and this objectification trickling down to younger and younger age demographics.

“Pleasant Rowland didn’t want girls to be positioned as either mothers — expected to return to the private sphere of the home without other forms of identity — but she also didn’t want girlhood to be a moment where you were preparing to become a sexual object,” Zaslow said.

-

More from The 19th

- How federal lawmakers achieved a ‘watershed’ year of progress fighting gender-based violence and sexual harassment

- More than ‘Don’t Say Gay’: Proposed national bill is latest move in fight over LGBTQ+ rights

- How Instagram and TikTok hashtags highlight gendered hate toward women candidates

Enter the American Girl doll and its accompanying brand, which focused on “girlhood bravery, doing good things in the world, and rejecting their mothers’ position in the private sphere.” But, Zaslow said, this commodification of a kind of second-wave feminist idea of girlhood was also “couched in a kind of neo-traditionalism — the focus on history, this notion of girlhood as a time of innocence and purity.”

Though the brand has evolved, this initial positioning has a certain stronghold in the minds of many consumers — which contributes to the kind of outrage being expressed by many self-identified conservatives at the content of the new book.

In a statement shared with The 19th, a spokesperson for American Girl said, “We value the views and feedback of our customers and acknowledge the perspectives on this issue. The content in this book, geared for kids 10+, was developed in partnership with medical and adolescent care professionals and consistently emphasizes the importance of having conversations and discussing any feelings with parents or trusted adults. We are committed to delivering content that leaves our readers feeling informed, confident, and positive about themselves.”

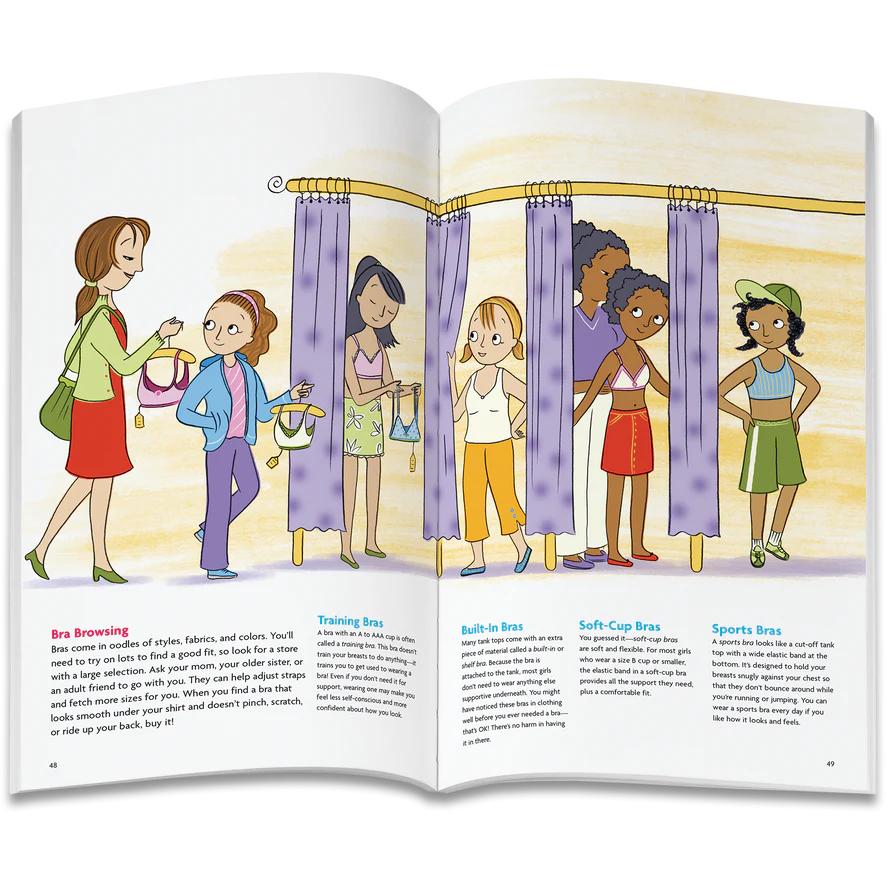

The first “Care and Keeping of You” book released by American Girl came out in 1998, and even then it had messages in it “about loving your body regardless of its size or shape, and information about who can and cannot touch your body,” Zaslow said. The books also reinforced more traditional ideas of gender and sexuality, firmly grounded in heteronormativity, with books like the “Smart Girl’s Guide to Boys” — a title which itself explicitly implies that all girls would be interested in boys from a romantic angle. (The book did contain information about sexual harassment.)

Zaslow said that American Girl has always been about generating profit first and foremost — which means that while it has never been a leader in social change, it has typically been incredibly responsive to it.

“I think for a lot of families, it is very welcome to see them say that gender expression can be interpreted broadly, that gender exists on a spectrum, that not everyone who is female was assigned female at birth and that the sex you were assigned at birth may not be how you identify,” Zaslow said. “The way this book is written positions the importance of mental health and of finding an alternative person to talk to if your parent is not the right person…. The focus of these books is always about talking to an adult when you are facing any kind of mental health issue. They always say, ‘Talk to a parent or another trusted adult.’”

“Body Image” is not the first time American Girl has drawn the attention of the right-wing media. Zaslow points to 2005, when the brand partnered with Girls, Inc., selling an “I Can” rubber band bracelet for $1. The proceeds were to benefit Girls, Inc., a nonprofit organization focused on empowering and enriching girls’ lives. But because Girls, Inc. had also publicly come out in favor of reproductive freedom and of girls who identified as queer, “the right-wing press went nuts saying that American Girl was pro-choice — which they have never come out as saying they are or aren’t.”

But for many people, especially those who grew up with the books and the dolls, the moments of co-branding alongside more explicitly progressive brands feels exactly like what the American Girl brand does represent, especially when viewed within the context of its informational titles like the Smart Girl’s Guides.

“This may be an unpopular opinion, but we believe that the brand has always been fairly progressive in terms of departing from gender norms. Though the earliest dolls, all White, cisgendered girls, weren’t exactly a great representation of all American girls, their stories departed from traditional gender norms and highlighted characteristics in them that hadn’t traditionally been considered feminine,” wrote Barrett Adair and Carter Black, the co-creators and co-owners of the Hellicity Merriman account on Instagram, which repurposes American Girl dolls and books into political and pop culture commentary memes, in an email to The 19th. “They appeared to keep that up in the decades since, and make strides to market their dolls and books to children who don’t identify as girls, including offering some dolls that are boys and revamping the Care and Keeping-style books to cater to boys. We wouldn’t necessarily say they’re ahead of the curve, but would say they’ve always made some strides to break from gender norms.”

Adair and Black said that while the American Girl brand’s informational titles have nothing to do with the dolls that first put the brand on the map, it is these informational books that “have cemented the American Girl brand in Millennial and Gen Z nostalgia.” Most children cannot afford American Girl dolls, they pointed out. “But their informational books are bordering on being a public service — they’re stocked in just about every library in America, and American Girl has free PDFs of them online.”

It’s also why the two co-creators say that these books are so important, and why the new “Body Image” book is such a critical addition to the series.

“In an effort to be factual and make the kids reading these books feel good and informed, we think it’s an incredibly logical and important step for the brand to include these new sections, and we’re not shocked that they thought to add them in. We’d say it takes a bit of willful ignorance to assume that the brand’s values don’t align with being gender-inclusive.”

Of the Girl’s Guide books, Adair and Black stressed that not only is the series, “entirely agenda-less beyond informing kids about puberty and all that comes with it,” it isn’t even seen as a primary revenue source for the company. That is, that the American Girl brand is making the effort to invest time and resources in producing inclusive — and now, gender-affirming — content without the goal of profit in mind.

“It would be a disservice to conservatives’ own children to make these books the latest target of their book-banning wrath, especially because the point of [the “Gender Joy” section] doesn’t even seem to be about driving conversation, but rather, making gender inclusivity an incredibly normal, expected part of how we educate children,” Adair and Black said. “There are plenty of things you could criticize American Girl for as a brand, but it shouldn’t be this.”

Lessa Pelayo-Lozada, president of the American Library Association, told The 19th that attacks on books — especially those for young people and especially those with LGBTQ+ content — are currently at an unprecedented level, with attempts at book banning in the United States reaching a level that “has not been seen since the McCarthy era” of the 1950s. From January to October of 2022, 781 attempts were made to challenge 1,835 titles. In comparison, in 2019, there were just 377 attempts made to challenge the circulation of books, about 566 individual titles.

Whereas in the past, challenges to books were most often made by individuals, Pelayo-Lozada described today’s targeted attempts to end access to books as often “organized attempts by groups who are submitting large lists of multiple titles that sometimes a library doesn’t even own.”

But books like “Body Image” that are written in consultation with experts to get relevant information to young people about their bodies and health in an age-appropriate way are exactly the kinds of books libraries are designed for, Pelayo-Lozada said. “Librarians and library workers are trained to make informed purchases for our collections, to build diverse collections to make sure that every reader that comes into our doors is able to access the information they need at the point of their lives in which they need it.”

In a time when “parents’ rights” have become a rallying cry associated with school board elections, curriculum content, COVID-19 policy and book restrictions, Pelayo-Lozada points out that the availability of books on topics like puberty and bodies is crucial regardless of a reader’s background or beliefs.

“We are focused on providing factually correct information, and while we respect every family’s choice about what their family reads together and what values they want to uphold, we can’t make that choice for other families,” she said. “It is not the role of libraries to tell folks how to parent, and it is not the role of parents to tell other families how to parent, either.”