When Michelle Collins graduated from nursing school in the 1980s, there was a workforce shortage. There were incentive programs and scholarships to encourage people to enter the field. Hospitals and other health systems created programs that would fund aspiring nurses’ educations with an obligated work contract.

But now, nursing faces another shortage, and while the pandemic played a big role, the problems are rooted in a demographic shift: An aging population is increasing the demand for medical care, a generation of nurses is retiring – and as they go, not enough nurses are staying to train the generation taking their place.

Collins, now the dean of the College of Nursing and Health at Loyola University New Orleans, said nursing shortages have been around throughout the history of modern nursing, like a pendulum, and experts knew this one was coming even before COVID-19.

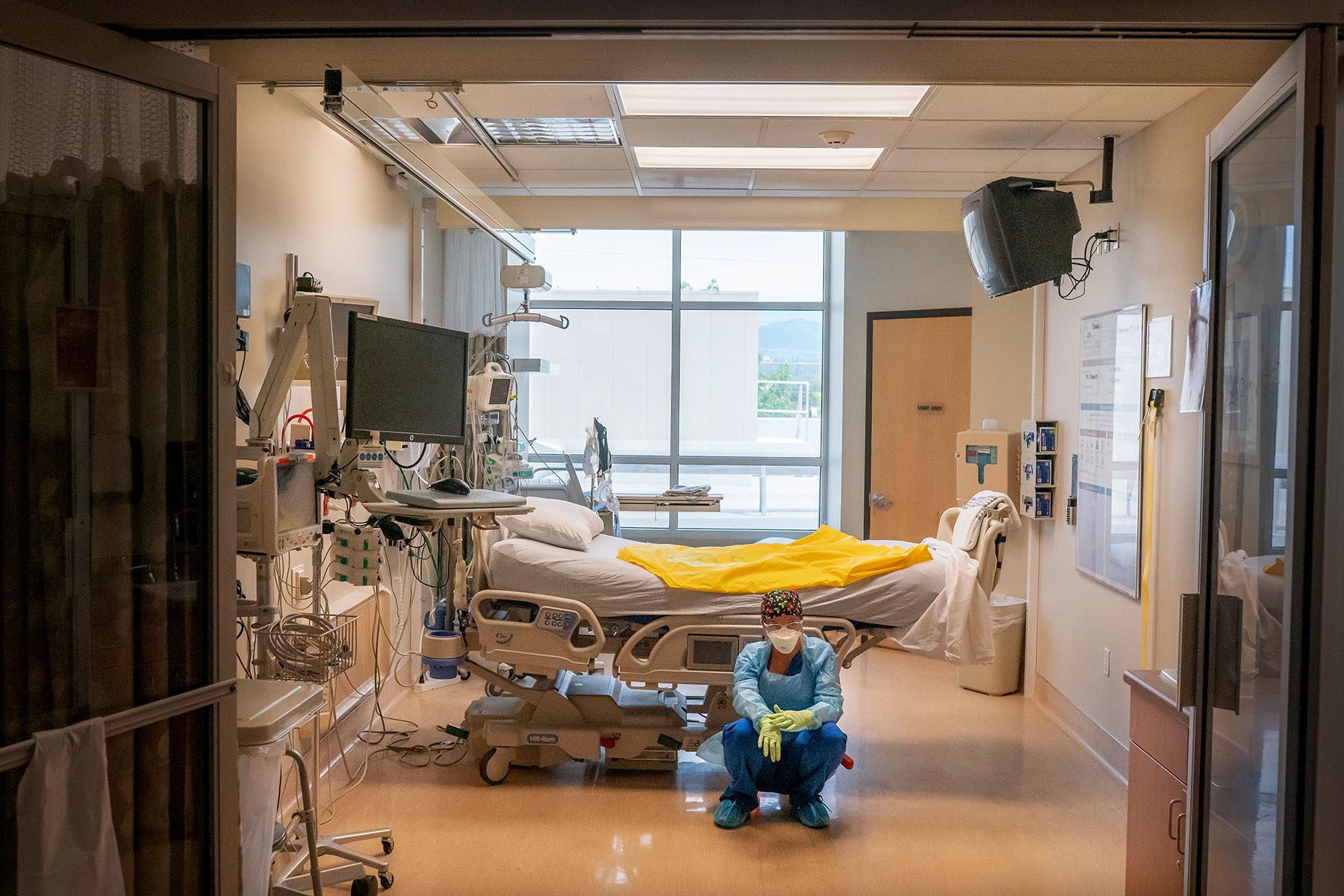

“The pandemic exacerbated a situation that was already becoming dire,” said Collins, who continues to work as a registered nurse. “So many nurses left the profession during the pandemic because of burnout. We have a huge number heading towards retirement and a shortage of nursing faculty to teach new nurses, making for a perfect storm.”

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the country will need more than 203,000 new registered nurses every year through 2026 to fill the gap in care left by a retiring workforce. The average age of a nurse right now is 51. In addition, the country’s population is aging and living longer: The 65-year-and-older population — the majority of whom are women — is the nation’s fastest-growing demographic and grew by more than a third in the past decade alone. Then came the pandemic in 2020, disproportionately affecting older adults and overwhelming the women-dominated health care industry.

The 19th spoke to experienced nurses and nursing educators about this moment and the challenges coming down the line.

What obstacles are blocking the nursing pipeline?

One of the biggest challenges to the future of nursing is that in addition to the nursing workforce retiring en masse, there is also a severe shortage of nursing faculty. Nursing schools turned away more than 90,000 qualified applications last year — the highest number in decades – because there wasn’t enough capacity, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

“We don’t have enough chairs in nursing schools because we don’t have enough nursing faculty,” Collins said. “And you have people who want to be nurses, but there aren’t enough seats in nursing schools.”

Lisa Rebeschi, a nursing professor and an associate dean of the School of Nursing at Quinnipiac University, said it’s been a challenge incentivizing nurses to move from a practice setting to the education arena.

“Right now, the salaries are very lucrative for nurses, especially if they’re doing travel nursing, and even if they’re not — academic faculty roles and the salary for those positions is not very competitive,” Rebeschi said. “It would actually result in a decrease in pay for someone to move from a practice setting to an academic setting, and with the economy right now, people aren’t willing to do that. Even with a lot of altruism, financially they’re not able to do that.”

On top of that, early-career nurses are leaving the industry or seriously considering leaving at abnormally high rates. The pandemic and its disproportionate impact on health care workers, including burnout and compassion fatigue, is a major factor. Up to 40 percent of nurses in the practice setting are “seriously thinking of leaving,” Rebeschi said, which is a significant difference from previous nursing shortages and should be a real cause for concern.

Collins said she’s seen a similar trend: “There’s a huge spike in the number of nurses who are leaving their career in the first three months of being a nurse. And not like going to another job — they’re leaving nursing, which is astounding to me. That’s horrible.”

Collins also pointed to the disruption in education caused by the pandemic. There are now several graduating classes that had to pivot to online-only courses and trainings during the pandemic. This shift to online education put a stress on faculty, but also impacted students in profound ways. Some programs did not require nursing students to work overnight shifts or handle an overloaded caseload, made more typical by the pandemic. Graduates then find out, very abruptly, that the reality of the job — sometimes multiple 12-hour shifts in a row or overnight shifts — does not line up with expectations.

“There’s a lot of things you can teach online, but nursing is one of the more difficult ones,” Collins said. “During the pandemic, we couldn’t get our students into clinical practice. Well, you can’t get your nursing license without touching actual patients, so how are we going to keep them educated and do it in a virtual way?”

As the workforce ages, Collins said nurses, particularly younger nurses, need mentors and the ability to create their own pipelines.

“If you have a new, excited, younger nurse and she’s just getting her feet wet in the clinical scenario, and she says in five years she’d like to be teaching in a nursing school — you say, ‘OK, let us help you with tuition reimbursement so that you can be working on your graduate degree part-time while you’re gaining your experience as a bedside nurse.’”

How did the pandemic impact these problems?

Nurses at the front lines of the pandemic faced surges in patient volume, equipment shortages, quarantines and social distancing from their own families, and secondary trauma as hundreds of thousands of Americans died in front of them. Thousands of health care workers died and one-third said they were leaving due to burnout.

Still, Rebeschi and Collins said the pandemic has actually increased interest in nursing as a career. The number of applications to nursing schools or accelerated programs for career switchers continues to increase.

“One positive thing from the pandemic is that it has really shone a spotlight on nursing,” Collins said. “We have people who are especially interested in accelerated bachelor of science in nursing programs — people who’ve been watching the pandemic and seeing all these nurses on the front line and decide they really want to do something to have more of an impact on people’s lives.”

In the short term, however, American health systems rely heavily on domestic travel nurses and nurses migrating from other — often low-income — countries to address urgent care needs. Nearly one in five of the 14 million health care workers were foreign-born in 2018, according to The Migration Policy Institute. The vast majority of foreign-born nurses working in the United States are from the Philippines — and the number of health care-related visa applications increased by more than 50 percent from 2020 to 2021.

What are some short-term fixes?

In addition to international assistance, hospital systems facing severe staffing shortages — like those caused by the pandemic — typically call on domestic travel nurses, who take temporary positions in high-need areas. During the pandemic, 95 percent of U.S. health care facilities reported posting jobs for or hiring travel nurses, according to data from AMN Healthcare, one of the country’s largest health care staffing agencies.

Colleen Marshall, the founding chair of nursing at Lebanon Valley College, said travel nurses are both a help and a hindrance. On one hand, they fill hospitals’ immediate care needs. But these nurses are also compensated up to 300 percent more than staff nurses that are already working under desperate conditions at these health systems.

“This is where compensation becomes an issue,” Marshall said. “Resentment builds, and nurses leave the profession. And in some instances, nurses from units that are well-staffed are being pulled daily to other lower-staffed units to fill in the staffing gaps — which subsequently harms morale and retention.”

Collins called the use of travel nurses a “double-edged sword.” They are necessary, but in the long run, they could be detrimental to the financial stability of the country’s health care facilities. According to the American Hospital Association, hospitals spent almost 40 percent of their total nurse labor expenses on travel nurses in January 2022, a significant increase from the 5 percent they spent in January 2019.

Younger nurses also tend to change jobs and employers more often than some of the older generations, Collins said, which leads to higher turnover rates and more time and energy spent onboarding new employees. A better solution, Collins argued, would be if health systems could find a way to invest in the employees they have, improve retention and spend money on in-house resources instead of on travel nurse salaries and expenses.

“There are no easy answers,” Marshall said.

What does this mean for patients and future care?

The turnover and the overall staffing shortages have a negative effect on the quality of health care — particularly for those who already live in rural locations and urban “care deserts” where hospitals have been shutting down and it’s harder to find practicing health professionals.

“There have always been areas [that] were underserved and [didn’t have] enough health staff to serve the population,” Collins said. “And so when you have a shortage, everywhere is affected and the places that were very short to begin with, they’re even more short now. There’s just not enough to go around.”

One major concern is that people will be forced to seek less safe, medically-unproven modes of treatment, Collins added.

In addition to the dangers of care deserts, Rebeschi said it’s important to remember that health professionals who are spread too thin, handling too many cases and working too many hours are more likely to make medical errors. A 2017 study found even before the pandemic that medical error was the third leading cause of death, with about a quarter of a million people dying annually — a rate much higher than other developed countries.

“The amount of deaths because of medical errors, it’s like a jumbo plane going down every day, and we don’t care about that to the extent that I think we need to,” Rebeschi said, noting it will likely get worse before it gets better.

What is currently being done to address the nursing shortage?

In recent years, Collins said there’s been a focus in medicine — and in particular nursing — on improving work culture, office conditions and overall quality of life.

Collins said she remembers a time when it was normal for nurses to be treated poorly by attending physicians in a power structure and hierarchy that left nurses at the bottom. For instance, when she was a student nurse decades ago, Collins said there was a surgeon who would regularly throw things in the operating room.

“He’d get mad and would just throw whatever was in his hand, and you had to duck out of the way,” Collins said. “And I’ve worked with physicians who came on the unit — this was when we did paper charting — and they’d pick up a chart and throw it and papers would go everywhere.”

Now, there’s much more emphasis on civility and equality in the workplace, said Collins, noting that there was once a time when nurses were expected to stand every time a doctor entered the room.

“There should be mutual respect for everybody on the health care team, whether you’re the environmental worker who is emptying the trash or you’re the surgeon who is doing the surgery. Everybody is important, and everybody has a role to play,” Collins said.

In addition to major shifts in workplace culture, many nurses now are demanding better working conditions, which largely impacts retention. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks strikes involving 1,000 or more workers. In 2020, the agency tracked five strikes involving health care workers. In 2021, there were four. And earlier this month, 15,000 nurses in Minnesota walked off the job for three days in the country’s largest strike of private sector nurses in history. One participant told PBS that the focus was on negotiating better staffing levels, paid family leave, protections for workplace violence and better compensation.

“Things like increased nurse-to-patient assignments, a lack of voice when it comes to their schedule and shift assignment were some of the nurses’ concerns in Minnesota,” Marshall said. “Nursing retention is often more about the conditions than it is the compensation.”

More external strategies are also being put into place to patch up the broken nursing pipeline.

Rebeschi said she’s seen media campaigns that promote nursing as a career and new partnerships form between health care systems and schools that give special attention to filling all available seats in nursing programs. Large health systems are working with schools to incentivize enrollment with scholarships and other pay-back programs to cover tuition costs. In return, many of the newly graduated nurses are contracted to work for a certain number of years within that health system.

For nurses already working in the field, Rebeschi said hospitals are finding creative ways to address the emotional and mental needs of their workforce — including yoga, mindfulness sessions, access to coaches who can provide extra support and increased flexibility when scheduling shifts.

“While these may demonstrate some effectiveness, real solutions will need to address the need to compensate and recognize the unique worth and value of the type of work that nurses do each and every day,” Rebeschi said. “Until we do that, we will not be able to make the significant level of progress needed to adequately improve the shortage in order to improve patient care.”