Sexual assault survivors in the military have long been unable to pursue civil charges against the U.S. government, but a ruling this month from a federal judge might signal a new way forward.

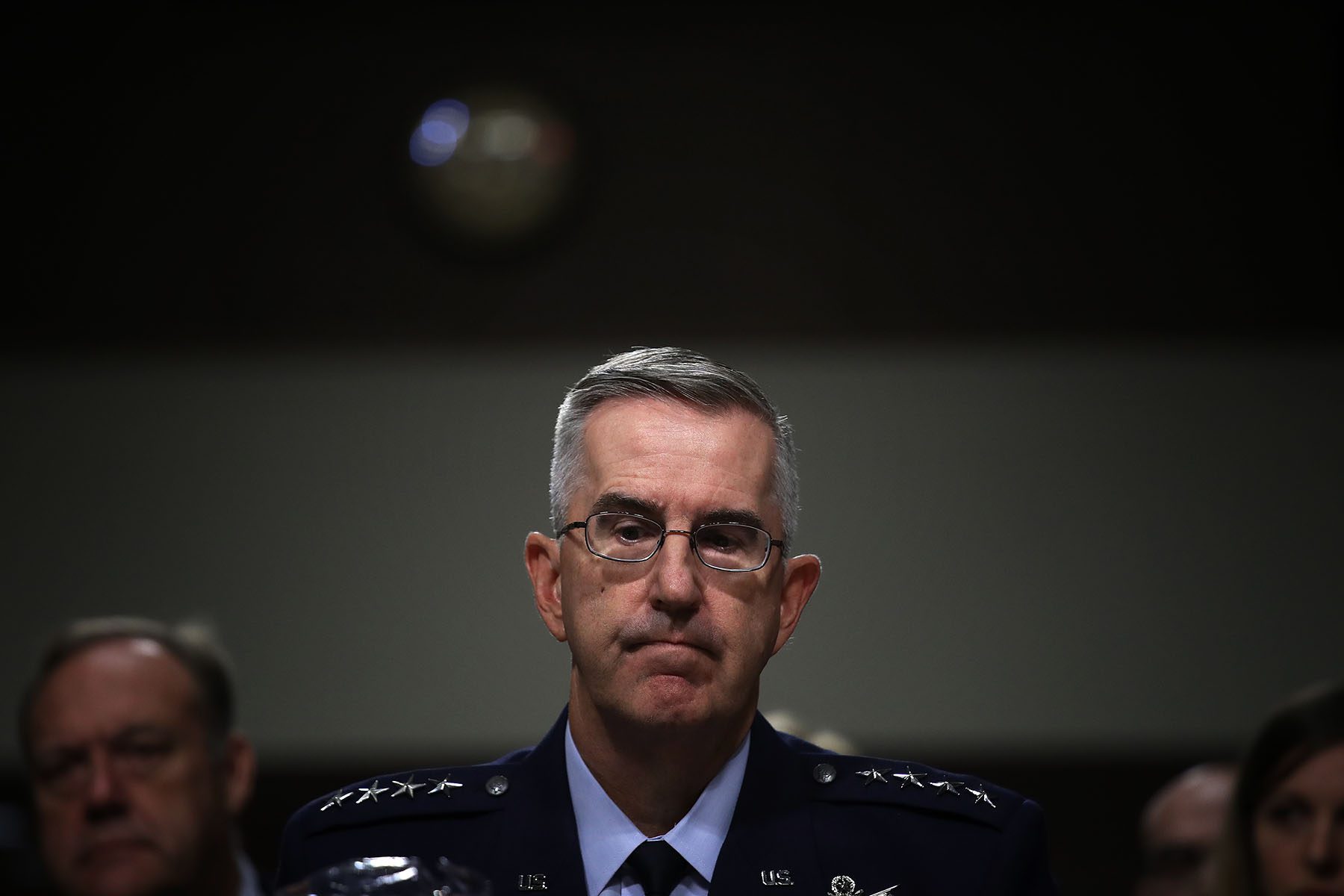

In 2019, Kathryn Spletstoser, a former Army colonel, filed a complaint in a California district court against Gen. John Hyten and their former employer accusing Hyten of sexual battery and assault. Hyten, who went on to become the military’s second-highest ranking officer, and the U.S. government moved to dismiss the charges on the grounds of the Feres doctrine, which was established in 1950 and prevents service members from suing the government for injuries arising from activities “incident to military service” — a term that has come to include virtually every injury incurred while on active duty. Under the Feres doctrine, service members who alleged they were raped by superior officers, harmed by exposure to nuclear testing or were victims of medical malpractice have been unable to file suits.

In an unprecedented move, the Central District Court of California in October 2020 denied the motion to dismiss because the “alleged sexual assault could not have conceivably serve any military purpose.” Hyten and the government then appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, where their motion to dismiss Spletsoser’s complaint was denied again earlier this month, on August 11.

In her opinion, the 9th Circuit’s Judge Johnnie B. Rawlinson said: “We cannot fathom how the alleged sexual assault in this case could ever be considered an activity ‘incident to military service.’” Now, unless the case is appealed to the Supreme Court, Spletstoser can pursue a civil trial.

Legal experts agree that the 9th Circuit’s “strong language” on this issue is significant because the case is likely to be appealed to the Supreme Court, which declined to review a petition challenging the Feres doctrine in 2019. The 19th reached out to several experts and victim advocates, most of whom submitted written information and expertise to the court in the Spletstoser case, to weigh in on what this opinion means for military sexual assault survivors.

How significant is the 9th Circuit’s opinion for military sexual survivors right now?

Lindsey Knapp, a veteran, lawyer and the executive director of Combat Sexual Assault, a nonprofit dedicated to helping military sexual assault survivors, called the opinion a “huge win.”

“We’re really excited about this and [survivors] should expect some larger, broader strategy coming out soon to help them specifically,” Knapp said.

Knapp, who regularly takes up cases involving sexual assault in the military, said she’s always trying to find attorneys who can assist or do the same kind of work because for many, these types of cases are a losing battle. Her organization’s new strategy following the court’s ruling is to recruit and create a broader pool of attorneys who will be paired with clients and placed in appropriate firms across the country, especially outside of the 9th Circuit. If similar cases are appealed to other circuit courts around the country, the Supreme Court is even more likely to take notice. Ultimately, Knapp said she hopes more survivors will have the legal support they need to hold perpetrators and those in power accountable.

“We don’t have a clear path to victory yet, but certainly the process has begun,” Knapp said. “And it’s looking very favorable. Spletstoser crawled so we could run.”

Lory Manning, a retired Navy captain and director of government operations and relations at Service Women’s Action Network (SWAN), said she’s less optimistic about whether the ruling will become the law of the land. But, she said, it caught the attention of many who have been working on this issue for years and could have broader ripple effects.

“Sexual assault survivors and their attorneys are watching closely,” Manning said. “If people can sue with an exception to the Feres doctrine because it’s off-duty, not incident to service — this can have wider implications. And the courts and the Congress will be watching that as well.”

Don Christensen, a retired Air Force colonel who served as the former chief prosecutor for the U.S. Air Force, said that the court opinion is “potentially massively significant.”

“The military has argued — in my mind, unbelievably — that rape and sexual assault are incident to service,” said Christensen, now president of Protect Our Defenders, an advocacy group dedicated to ending sexual violence in the military. “At least the 9th Circuit put out some pretty strong language that there’s no way that a rape or sexual assault can serve a military purpose. There’s nothing unique about rape and sexual assault that requires military expertise to abjudicate.”

Deshauna Barber, an Army veteran and chief executive of SWAN, said the ruling gave her hope.

“I personally think it’s not a good look, not a good representation of the image that the military tries to push through when it comes to being noble and integrity-driven — when you have a colonel suing the government for the actions of a general during military service,” Barber said. “So in my mind, I’m not saying she’s obviously going to get the justice that she deserves, but I think at bare minimum, this is putting pressure on the military to make changes.”

-

More from The 19th

- What is ‘soft’ censorship? When school districts don’t ban books, they still limit student access

- Family planning clinics, a safe space for transgender patients, face a new battle after Roe v. Wade

- ‘It’s really crushing’: Trans students in higher education face misgendering, isolation and debt

Why has it been so difficult for military sexual assault survivors to take their cases to court?

The military justice system is separate from that of civilians. Criminal offenses are handled and investigated internally by the military, and service members’ ability to seek civil trials has long been limited.

Before World War II, the U.S. government operated with “sovereign immunity” and could not be sued. At the war’s end, Congress enacted the Federal Tort Claims Act to allow for federal employees to recover damages when their injury is the result of the government’s negligence or irresponsibility. However, the legislation includes a two-year statute of limitations for those seeking recourse and came with a major exception: service members could not sue over any injuries incurred in battle during wartime. The idea was that civilian courts in these cases would undermine military discipline.

One Supreme Court ruling in particular, known as the Feres doctrine and established after the war’s end, limited service members’ rights further by barring service members from suing the government over any injuries incurred while on active duty. Rudolph Feres, a decorated World War II veteran who parachuted into France on D-Day, died in a barracks fire after returning to the United States. His widow sued the government, arguing that the government was negligent by housing her husband with a defective heating system and failing to maintain a fire watch. The Court ruled that the government was not liable for Feres’s death.

Though typically applied to cases of medical malpractice, military missions and military-sponsored recreational activities — the Feres doctrine has, over the years, become more expansive to include different circumstances, including environmental contamination and sexual assault allegations. Women are the largest-growing demographic in the military and reports of sexual assault and retaliation in the military continue to rise.

The Supreme Court has continued to debate the use of the Feres doctrine over the years, and several justices have voiced their disapproval of a doctrine that allows citizens a recourse not afforded to members of the military.

“Feres was wrongly decided and heartily deserves the widespread, almost universal criticism it has received,” Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in 1987.

In 2019, the Court refused to reconsider the doctrine. In that case, which also came out of the 9th Circuit, a man filed a suit against the government after his wife, a Navy lieutenant, died at a naval hospital due to a complication following childbirth. In response, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote: “Such unfortunate repercussions — denial of relief to military personnel and distortions of other areas of law to compensate — will continue to ripple through our jurisprudence as long as the Court refuses to reconsider Feres.”

Then in 2020, Congress made a notable change to the Feres doctrine when it passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) including an exception “for personal injury or death incident to the service of a member of the uniformed services that was caused by the medical malpractice of a Department of Defense health care provider.”

Still, the doctrine remains largely intact.

What led to Spletstoser’s lawsuit?

In December 2017, Spletstoser attended a two-day defense forum in Simi Valley, California. The evening after the forum concluded, Spletstoser, who was one year into her tenure as a leader within the highest echelons of military command, was getting ready for bed when she heard an unexpected knock on her hotel door. It was Hyten, a general and her superior who also attended the forum, wearing workout clothes. He was staying in the room across the hall. According to court documents, Hyten grabbed, groped, kissed and rubbed his body on Spletstoser against her will — all while declaring he wanted to “make love,” she alleged.

In a 2019 interview with The New York Times, Spletstoser said Hyten had tried to kiss, hug and touch her inappropriately while in the office or on trips multiple times in 2017. She had even threatened to tell his wife but said she had no intentions of coming forward because she thought Hyten would soon retire. But when Hyten was nominated by former President Donald Trump to the second-highest ranking military job in the country, Spletstoser said she had a “moral responsibility” to speak out.

Hyten denied the allegations in front of the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2019 at his confirmation hearing to be the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: “I want to state to you and to the American people in the strongest possible terms that these allegations are false. … Nothing happened. Ever.”

He retired from the military in November 2021, and became an executive and adviser for Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s space company.

What happens next?

The court opinion is a “great first step,” but Christensen cautioned that more still needs to happen: The case has yet to be adopted in other circuit courts or appealed to the Supreme Court.

For now, the ruling only applies to assaults that occurred within the 9th Circuit’s jurisdiction, the largest circuit court of appeals, which covers Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam.

Legal experts said it was most likely that the case will be appealed to the Supreme Court — which might take years to play out. Lorry Fenner, a retired Air Force colonel and SWAN’s incoming director of government operations and relations, said even then, she is not sure the Court will side with the 9th Circuit.

“It is traditional that the Court defer to the military,” Fenner said. “Congress defers to the military. In my opinion, with the current constitution of this Supreme Court, I can’t see them not siding with the military.”

Though the court process could take time, experts agreed Congress or the military itself might step in. In recent years, there have been other major changes to the military justice system, particularly when it comes to sexual assault.

Last year, Rep. Jackie Speier, a Democrat from California, spearheaded legislation which removed cases of sexual assault, domestic violence, stalking, murder, manslaughter, kidnapping and other special victim offenses from the chain of command. These specific crimes are now investigated by independent prosecutors. Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s broader companion bill — which would have removed military commanders entirely from the chain of command in all serious crimes — was stripped from the legislation at the last minute but is expected to be included in the 2023 proposed NDAA.