LEWISTON, Maine — JulieAnn Fitzy couldn’t ask her doctor for help. She wasn’t out yet to her family, many of whom went to the same primary care practice as she did. What if they found out? And besides, her physician wouldn’t know where to find someone who offered hormone therapy.

It was 2018, and Fitzy had started looking for gender-affirming care. In her hometown of Westbrook, Maine, the options were nonexistent. She looked in Portland, the biggest city, only 20 minutes away. Still, she found no help.

“Nobody was doing it in Maine,” Fitzy recalled. “My primary care doctor had no idea. Since then, she’s actually sent me emails asking me for information.”

Fitzy, a 57-year-old former commercial driver and paramedic firefighter, eventually found an appointment 35 miles north, in Lewiston. That August, she made her first drive to the clinic, one of eight outposts of an organization called Maine Family Planning that provides gender-affirming care. Right away, she knew things here would be different.

“They’re very open here,” she said. “Beyond friendly — they’re very accepting.”

Most critically, she added: “They get my gender right.”

That isn’t a given in health clinics. Only recently, an intake coordinator at a Portland hospital consistently misgendered Fitzy. Another physician at that hospital made inaccurate assumptions about her anatomy. It’s the kind of mistake that never happens in Lewiston.

Since 2018, other clinics closer to her home have started providing gender-affirming care. But the staff at Maine Family Planning are special, she said. She’ll still drive an hour each way to stay their patient.

In Maine, this network of clinics is a lifeline for people seeking reproductive health care that is often unavailable in a regular doctors’ office. Across this state, the most rural in the country, 18 clinics operate under Maine Family Planning’s umbrella, and dozens more get support from the organization. They offer birth control, treatment for sexually transmitted infections, HIV prevention, sex education and wellness check-ups. In 1997, they began providing abortions. Eight years ago, they began providing gender-affirming care.

The farther from Portland one gets, the more likely Maine Family Planning will be the only place people can reliably get reproductive health care. It’s certainly the only place many can afford: Bills are based on what patients can pay. Most patients are on Medicaid, which insures low-income people — 1 in 5 people in Maine are covered through that program, about in line with the national average.

This care isn’t profitable — Maine Family Planning deals with shoestring budgets and delayed renovations. Most critical to its existence is Title X, a federal program that allocates millions of dollars each year to support reproductive health clinics serving primarily low-income people. The money consistently makes up close to a quarter of the entire network’s budget, with the rest coming from private grants, state funding, earned income revenue and investment income. Without Title X, Maine Family Planning wouldn’t exist.

Clinics that have long relied on the program are only now recovering from a yearslong effort by former President Donald Trump to stop Title X clinics from even discussing abortion, what providers referred to as a “gag rule.” Under the Trump administration, clinics that referred patients for abortion services were ineligible for federal dollars.

When Trump changed Title X, Maine Family Planning quit the program, leaving it to rely on cash reserves and fundraising to stay afloat. For close to three years, Maine was one of only four states in the country with no federally funded family planning whatsoever.

The Trump policy — which at the time had little precedent — was reversed under President Joe Biden, and the change took effect this year. But Trump’s success means future Republican administrations are all but certain to bring back the Title X gag rule. Meanwhile, an ensuing legal fight, spearheaded by a dozen Republican-led states, could bring back that policy permanently.

Maine Family Planning, the state’s only Title X recipient, uniquely illustrates what happens when family planning clinics lose federal support — here, clinics already tried to live in that world. It kept doors open, but it wasn’t easy.

The stakes — already high — are now raised further. The undoing of Roe v. Wade, which protected federal abortion access for nearly 50 years, is putting pressure on states like Maine, where clinics are already experiencing an increase in patients coming from out-of-state for the procedure. Agreeing not to refer patients for abortions would have implications well beyond the state’s borders. But losing funding again — potentially longer term — could be financially devastating. Staff aren’t sure if their institution would make it if they had to do it again.

Caught in the middle are people like Fitzy. Living without the care Maine Family Planning provides is inconceivable.

“I can’t imagine, if this closes, what I would do,” Fitzy said. “This place — they need to be here to help as many people as they do.”

Title X launched under President Richard Nixon in 1970, and Maine Family Planning opened its doors just a year later. The politics of the program haven’t always been contentious. But though it historically received bipartisan support, one president before Trump put Title X in the crosshairs. Ronald Reagan, considered by many historians and anti-abortion activists to be among the early leaders of the modern anti-abortion movement, attempted a Title X change similar to Trump’s gag rule. But his change, which was never enforced, was reversed in 1993 by Bill Clinton, one of the new president’s first moves in office.

Part of the program’s across-the-aisle appeal: It is not allowed to directly fund abortion. Federal dollars only go to support the contraceptive care and basic preventive services Title X clinics provide. Services like abortion or gender-affirming care are paid for through other sources of revenue such as private grants.

Despite those guardrails, Trump seized on the program’s association with abortion and abortion providers. As a candidate, he promised to “defund Planned Parenthood” — the biggest single recipient of Title X funding. His gag rule for funding took effect in July 2019, leaving clinics with two choices: abandon any mention of abortion or drop out of the program. More than 1,000 family planning clinics across the country lost funding.

One month after the change took effect, Maine Family Planning announced it was pulling out of Title X.

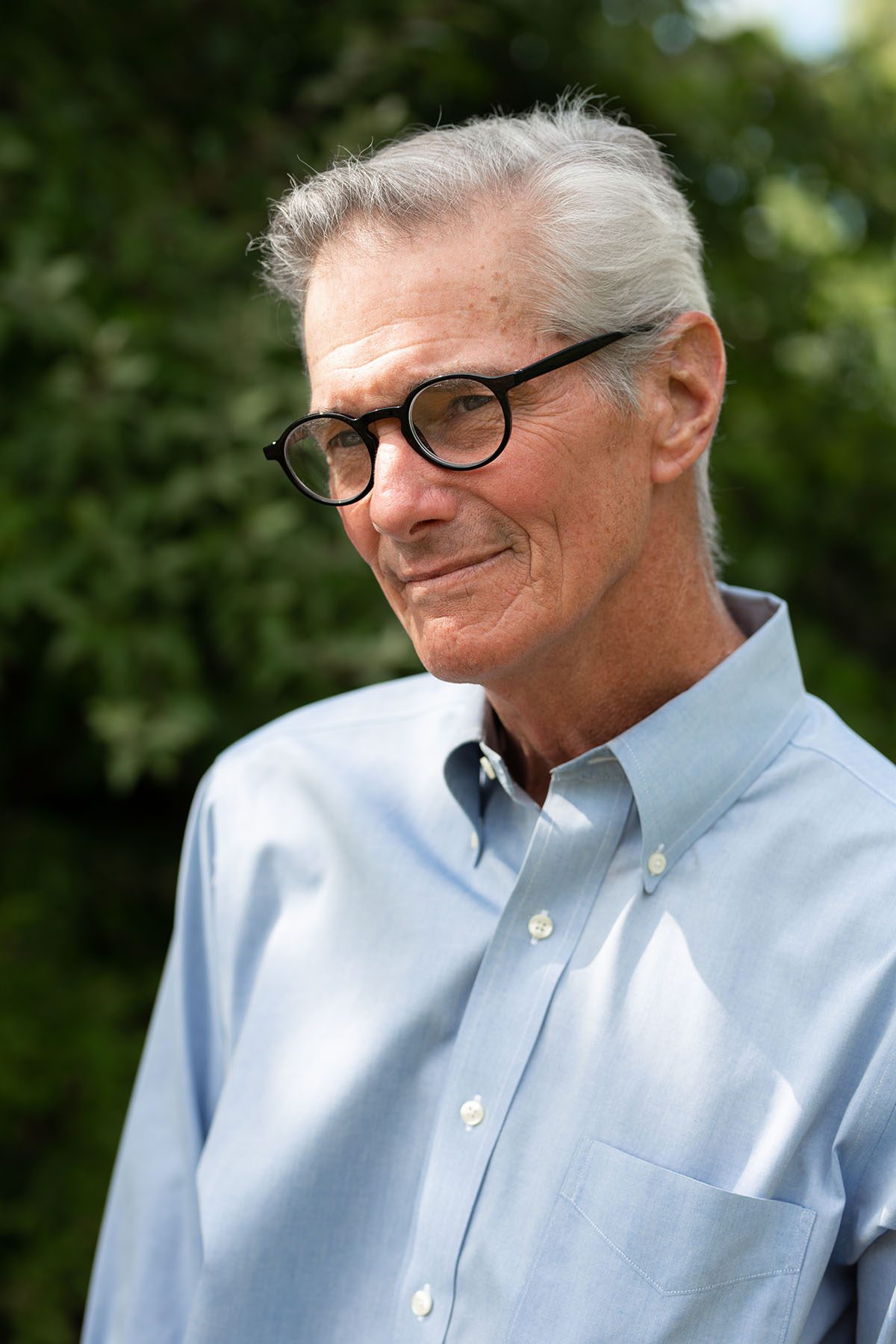

“We knew how vulnerable we were, especially once we began providing abortion care,” said George Hill, who has run the organization since 1991.

For decades, Maine Family Planning built up a reserve fund of about $4 million dollars, half the money it would take to operate the program for a full year. When federal funding disappeared, they used those reserves and went on an aggressive fundraising tour. Hill sought private donations from everyone he could — local organizations, national nonprofits — to fill the gaps. The clinics were to be as frugal as possible.

It worked. No jobs were cut. No providers got raises, but no clinics were closed.

When Biden was elected in 2020, he vowed to restore Title X eligibility to clinics that discussed abortion. Soon after his inauguration, his administration took steps to undo the Trump policy. The change took effect this year — not a moment too soon for the Maine clinics.

“I can’t imagine what life would be like if Trump had been reelected,” Hill said.

After their eligibility was restored, Maine Family Planning qualified for what is known as a “dire needs” grant, receiving just under $160,000 from Washington this January. At the end of March, the organization received just under $2 million — enough Title X money to fill out its budget for this year, comparable to what they used to get. Things are back to normal. Everyone is relieved.

But the Trump administration’s brief, unprecedented success makes it all but certain that future Republican administrations will attempt to block clinics from offering abortion referrals. Senate Republicans pushed a vote in late April to restore Trump’s Title X policy that failed 49-49, on almost pure party lines. Sen. Joe Manchin, the West Virginia Democrat, joined Republicans, and Sens. Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski, of Maine and Alaska, voted with Democrats.

“I don’t see any reason [those rules] wouldn’t come back under a new administration,” said Sara Rosenbaum, a health law professor at George Washington University and expert in Title X. “Clearly there are people who are going to keep trying and trying, and future administrations may keep trying and trying to knock out any information being given.”

And the organization faces another potential threat. Last fall, after Biden took steps to reverse Trump’s rule, Ohio and 11 other Republican-led states filed a lawsuit arguing that the Title X statute shouldn’t include clinics referring for abortion services. The only acceptable interpretation of the law, according to the suit, is to give family planning money to clinics that avoid abortion entirely, including referring patients to other health centers that provide it.

The argument goes against decades of family planning policy, running counter to a 1991 Supreme Court ruling Rust v. Sullivan, in which the majority held the Title X statute is ambiguous enough that the president can decide who is eligible for the federal funds.

The Ohio lawsuit is currently before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. So far, its arguments haven’t succeeded. The Sixth Circuit declined the conservative states’ request to block Biden’s new family planning policy and is still weighing whether to hear oral arguments on the case. The case hasn’t moved for months. It’s unclear if it will, or what the outcome might be.

Longer term, there is the question whether they might end up bringing their case to the strongly conservative U.S. Supreme Court. Some experts are surprised that the plaintiffs haven’t yet tried to amend their lawsuit in the wake of Roe’s overturn, offering an argument that builds on states’ newfound power to ban abortion.

Still, the absolute earliest the Supreme Court could hear a Title X case would be next year. If the case does make it to the high court, a ruling against the Biden administration could wreak havoc for clinics, some policy experts said.

“Just as the Title X program might be getting back on its feet, and where the network would feel more similar to what it was, you could have a ruling that seeks to undo all of that,” Laurie Sobel, associate director of women’s health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation.

The issue has garnered little national attention, even as Republican presidential contenders are soft-launching their 2024 campaigns, and even with Trump expected to soon announce his own reelection effort.

Despite that, Hill doesn’t have time to worry. There’s too much on his plate. But still, he fears that “this case — or a case like it — could pose an existential threat to Title X.”

“It’s a constant concern,” he said. “But it’s not one that distracts us from the work we need to do.”

And if the loss of Title X funding were more permanent, the future of Maine Family Planning looks bleak. This past time, everything worked out, but it’s not a viable long-term strategy, Hill said.

“It was a shock to our system,” Hill said. “We are under absolutely no illusion that that kind of effort could be sustained for more than a year or two.”

The fight over Title X comes at a pivotal moment for reproductive health care. After the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, 12 states have begun enforcing laws that ban most or all abortions. In Wisconsin, clinics have stopped providing the procedure out of fear surrounding a decades-old law that was never repealed. More bans are set to take effect soon.

In Maine, abortion is legal until fetal viability, and people have begun traveling from out-of-state to get abortions at Maine Family Planning, Hill said. It’s not a large number of people, he noted — Maine is, after all, far smaller than nearby Boston or New York — but it’s enough of an increase to register. From a moral standpoint, Hill said, it would make it only more difficult to ever consider foregoing the clinics’ ability to provide or even refer patients for abortions.

But on the other hand, the prospect of ever again dropping out of Title X — of losing that critical source of funding — would likely mean someday having to shut down some of Maine Family Planning’s clinics. In the towns affected, patients would lose access to affordable contraceptive care, abortion resources and gender-affirming care. The latter two are particularly difficult to replace; health professionals who provide it are hard to come by in rural Maine.

The people most harmed, staff fear, would be patients, for whom such care can already be expensive, and otherwise difficult to attain. Without Maine Family Planning, some might travel hundreds of miles — even out of state — to find a health care provider who can help them.

Christina Theriault, a nurse practitioner who runs two northern Maine Family Planning clinics, was terrified when the clinics quit Title X.

Her clinics serve small communities. There is one where she lives, Fort Kent, population 4,000, open two days a week, virtually at the Canadian border. The other is an hour south, in Presque Isle, home to 9,000 people. For more than 100 miles of often snowy, winter-worn roads, she is the only person who provides medication abortions, the most common method for people within the first trimester of pregnancy. She is the only person who provides gender-affirming care for almost 200 miles.

When Maine Family Planning left the program, she knew finances were shaky. What if her job was cut? Where would she go? And without her — who would take care of her patients?

Theriault started taking meetings with other clinics. She remembers one vividly. If she came on board the family practice, the supervising physician told her, she would have to stop doing abortions. She would have to stop providing gender-affirming care.

“I came with a big red flag for that one,” she said. “I did reach out to a lot of people. Thankfully, we’re still standing.”

Theriault loves her job. For many patients, the birth control she provides is the only one they can afford. In Fort Kent, she lives around the corner from the clinic. She’s the local expert. They trust her. They know her.

“There are people that reach out to us naturally. We’re a known entity in the community,” she added.

Meredith Hunt, another nurse practitioner, felt that strain, too. She’s a former Peace Corps volunteer who likens her service in Thailand to providing care in Waterville, a college town just an hour north of Portland. There, just like in Thailand, she’s the health person: the one people rely on for colposcopies they can actually afford, the one who provides gender-affirming care. And just like in the Peace Corps, working in family planning means making things work on a tight budget — stretching clinic dollars to see every patient possible.

After 2019, the comparison became even more acute.

Even if Title X dollars only went to one kind of care the clinics provide, their loss affected everything. Whenever something broke, clinic staff waited until it was absolutely necessary before ordering a replacement. Maybe they would buy a used model. Or an older model. They avoided ordering extra medical supplies.

If Hunt worked extra hours — and she always works extra hours — she made sure not to mark it on her time sheet, worried the clinic couldn’t afford to pay her.

“I get paid for seven and a half hours,” she said. “Let’s just leave it at that.”

And when a nurse or staffer called out sick, common as COVID-19 raged through Maine, they simply went without that person for the day. Hunt sometimes ran her entire clinic by herself. And in turn, that limited how many appointments were available.

On those days, “my job was to do everything,” she recalled. “I have a front desk person who signs them in, but then I’d do the whole intake, do blood pressures, do all that kind of stuff, do the exam. And then I’d have to clean up after the exams, I’d have to wash the speculums at the end of the day, plus process all of the labs and all that stuff that comes through.”

The work the nurses are doing at Maine Family Planning has never felt more vital.

The pandemic opened new doors for family planning providers, and particularly those who perform abortions. In the spring of 2021, the federal Food and Drug Administration moved to let medication abortions be performed over telemedicine — the nurse or doctor involved could talk to a patient virtually and then mail them pills.

“COVID changed the way we were able to provide care,” Theriault said. “It actually made abortion more accessible for my patients.”

As more patients return to in-person doctors’ visits, the virtual abortion option has stayed. And Maine Family Planning has expanded its telemedicine model in other ways. Hunt prescribes birth control over virtual visits. For patients who might not be able to drive two hours to come into the clinic, she can diagnose and treat a urinary tract infection over video-conference. Nurse practitioners can offer hormone therapy over telemedicine, too.

It’s an invaluable resource, said Hunt, especially for patients who live somewhere in the state where a rainstorm or surprise snow — hardly uncommon in the northernmost eastern state — means a long drive is no longer safe.

And the clinics’ work in gender-affirming care – now only six years old – feels more meaningful, especially as state legislatures attempt to limit access. Now that Maine Family Planning has rejoined the Title X program, its leaders say they hope to push the federal government to prioritize supporting gender-affirming care.

“That would be another exciting opportunity for us, as Title X grantees — to be a louder advocate for including more LGBTQ care within Title X,” said Mareisa Weil, the organization’s vice president for community engagement.

But the subtext is hard to ignore. Many here worry that it’s not a matter of if the Trump gag rule comes back — it’s a matter of when.

In 2019, Maine Family Planning could make the case that they needed a short-term infusion of cash. And they were the rare clinic that had lost federal funding. It was a compelling argument, and one that convinced donors to help them fill in the financial gaps.

In 2024 or 2025, though, things will likely look different. Maine is a smaller state, and abortion rights are enshrined by state law. And with Roe overturned, national organizations — the same ones that helped keep Maine Family Planning afloat the past few years — will be facing much other, arguably more pressing needs.

“The landscape has changed,” Hill said. “The competition — the need for funds in states where Roe v Wade has not been codified in the way that it has in Maine is going to be pretty great.”

“We have some very loyal supporters,” he added. ‘But they, by themselves, here in Maine can’t support this organization.”

In 2019, Hill’s team considered closing some clinics, if new money didn’t materialize to replace the Title X funds. But those discussions didn’t get very far — they never even identified which sites might be shut down.

If the Trump version of Title X were restored, Maine Family Planning would consider litigation, Hill said. But if that failed? They could consider dropping abortion referrals. But it’s a tough ask to make of providers. They could also consider leaving the federal program — and probably closing down some clinics for good this time.

“It would definitely do some serious damage to our rural areas,” Theriault worried. In 2019, she speculated about whether one of her clinics could be targeted for closure. But more likely, she believes are other, even more remote sites — ones that are open only once a week, and that serve towns even smaller than hers.

She can’t imagine providing care without the offer of abortions. Before her, the closest abortion site was in Bangor — a three- to four-hour drive each way, depending on whether a patient comes from Presque Isle or Fort Kent. That’s a whole day trip. And for many of her patients, it’s unaffordable.

“There are a lot of people who just wouldn’t get care at all if we didn’t exist,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Maine Family Planning's funding sources outside of Title X and the number of years it has been gender-affirming care. The article also did not accurately reflect how abortion is protected in Maine.