When 20-year-old Vanessa Guillén went missing from her military base at Fort Hood in 2020 after reporting sexual assault, Karina Lopez was angry. Lopez, an Army veteran, decided to tell her story on social media: She had been assaulted while stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, two years earlier.

“This isn’t just a one-time thing,” Lopez said in a new Univision News documentary that premiered Thursday. “I reported it, and I fought. I’ve gone through the trauma and the retaliation that I faced, and now you have a missing soldier that was sexually harassed. I put my picture beside Vanessa’s and wrote my story.”

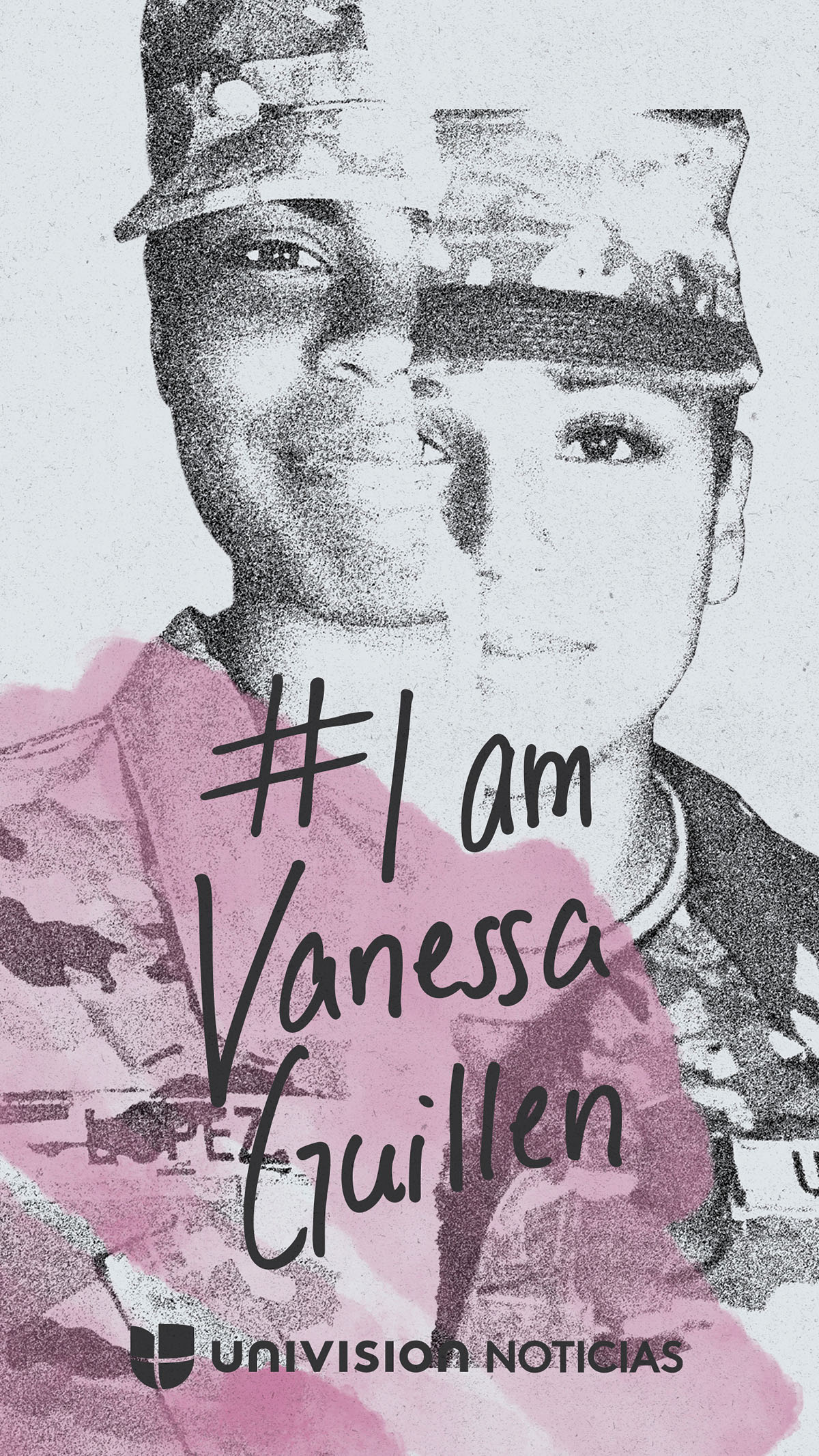

She ended her post with a hashtag: #IamVanessaGuillen. Her story went viral, and thousands of women from different generations, stations and ranks spoke up about their own experiences and demanded change — a movement that is now at the heart of the documentary, named after Lopez’s hashtag.

Guillén’s remains were eventually found near a river about 20 miles from the base. Investigators detained a fellow soldier suspected of beating her to death, but he shortly escaped and fatally shot himself. Separately, about one year later, officials determined that she had been harassed by a different soldier.

The documentary centers on Lopez, who left Fort Hood one month before Guillén went missing. In an exclusive interview with The 19th, Andrea Patiño Contreras, the director of the film, spoke about the resilience of survivors of military sexual violence and their efforts to reform the justice system and reclaim their lives.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mariel Padilla: Can you tell me the exact moment when you knew that you were going to make this documentary — and what led you there?

Andrea Patiño Contreras: When the Vanessa Guillén case happened in 2020, my colleague David Adams [at Univision News] was reporting a lot on that and through that reporting, another case came to us: Karina’s case. I hadn’t worked with military issues before, but I had a lot of experience working on gender and sexual violence. I flew down to see Karina in late 2020 and very quickly realized this is a story we had to tell. I was struck by her clarity; she’s very articulate and self-aware. She was especially disturbed by what happened to Vanessa; she knew it could have been her. Karina was able to communicate a lot of things that I have never heard someone say the way she explained it — the way she was experiencing PTSD, very complicated emotional states.

I came back from that initial trip feeling like there was a very important story there. At that point, it was very clear to me that we were going to make a documentary. For the most part, I was doing short docs — anywhere from five to 15 minutes. We actually published a short story, about five minutes, on Karina’s case in January 2021. But we continued talking and reporting, we interviewed Protect Our Defenders, requested access to visit Fort Hood and visited the Guillén family. We also started meeting more people and survivors whose stories I thought were great, and I wanted to include a couple of people that represent an older generation that didn’t feel like they could speak. I was like, ‘OK, this is clearly a longer piece.’

From gaining military access and investigating classified documents to navigating a pandemic, the reporting for this film couldn’t have been easy. What kinds of challenges did you face during the process?

After that first meeting with Karina in 2020, I went down again and started filming a little bit with her and her family. She told me the interviews and cameras were overwhelming and emotionally draining. She wanted to keep filming but didn’t know when she would be ready again. I told her I could wait as long as she needed, and we stayed in touch for the next few months.

In the meantime, during the first part of 2021, we requested access to Fort Hood and actually surprisingly got it fairly easily. At that point, the independent review committee had just released a few months before their findings. I think they were very much under the eye of everyone and wanted to give access to people. So we requested the maximum kind of access we could get, which was three full days, and talked to as many people as we could. Still, accessing substantial information or getting specific answers about individual cases was really difficult, if not impossible.

By the summertime, Karina said she was ready for me to come back. She was dealing with pretty intense PTSD and after a few days of filming, she was drained again. There was a lot of negotiation and really open conversations — it was a very interesting, new and challenging filmmaking process for me. I grew and learned the importance of trauma-informed reporting. You can’t rush a story like this.

The documentary is in English but will have Spanish subtitles. While directing, who did you imagine would one day be your audience?

With Univision, our audience is primarily Latino, and that’s a really important population for the Army as it’s the fastest-growing. It’s important that the Latino community see, but it’s also become clear that this project has resonated with a lot of veterans. In some ways that speaks to Karina’s viral post: There are so many people who have gone through similar experiences. People crave a sense of community, and I’ve noticed that a lot of veterans are excited and want to see the film because there’s something very powerful about when you realize that you’re not alone.

Ultimately, we would like for the film to be seen by not only military or military-adjacent people — but anyone, anyone who might learn and understand something new.

When you’re working on a long-term project like this, things are constantly changing. There was an independent investigation into Fort Hood’s command, the annual defense bill was modified and lawmakers pushed for further military justice reform. How did you know that the documentary was done?

I don’t know that you ever know that you’re done. I think I could have edited more. I could have done different things, but at some point I had to close this story. It was definitely really hard to keep track of all the changes in legislation and also trying to strike a balance between explaining that information as accurately and nuanced as possible and not being too information-heavy.

There are some universal themes that are probably not going to go away in the military any time soon. Obviously, this is still happening. Culture doesn’t change overnight, so those things will remain relevant unfortunately. I don’t know if there was ever a point that it felt like filming the documentary was over because we honestly could have kept going. But we had to make that call.

What do you hope people take away from the documentary?

I hope it can be used as an educational tool, one that the military might be able to use in training and reform at a higher level. I would also love to have community screenings, so that it helps further change in whatever way that may be.

On a personal level, I’m a survivor myself with sexual assault under completely different circumstances. In my case, my perpetrators were arrested and went to jail and were prosecuted. I have always known that that’s such a rarity, but this reporting gave me a deeper understanding of what justice means and what that can do to you, your mental health and your physical health — or the lack thereof. I have a much more profound understanding of what justice gives you, and we’re denying so many people that right.

I hope people watch “#IamVanessaGuillen” and demand changes from these institutions that have for so long not been held accountable. There is hope at an institutional level and at an individual level. So many of these women have faced tremendous obstacles but have been able to find the tools to have a fulfilling, happy life. And that’s true for Karina. She doesn’t want this terrible thing to define her.