INDIANAPOLIS — High school students, religious leaders, doctors, nurses, mothers, advocates, a former legislator from a neighboring state and a staff member from the attorney general’s office stood one by one before an Indiana Senate committee. Without exception, they all argued against SB 1, a bill that would completely ban abortion with a few narrow exceptions, including if the life of the pregnant person is at risk and in cases of rape or incest, though some thought it was too weak while others argued against any new restrictions.

After nearly eight hours of public testimony from about 60 people, the Indiana Senate Committee on Rules and Legislative Procedure on Tuesday voted 7-5 during a special session to advance the new abortion restrictions. Indiana is the first state to meet and focus on new restrictions since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which had provided a federal right to an abortion. The full Senate will convene Thursday to offer and debate amendments to the bill, and a final vote is expected on Friday.

Hundreds of people had registered to speak, but limited time meant only a fraction were able to take the microphone. Each witness had three minutes to convey their opinion, and many faced questioning from the lawmakers.

Not a single person testifying was in favor of SB 1: Many, including all of the anti-abortion organizations that were represented, didn’t think the bill went far enough to restrict abortions. Some felt the language was too vague and open to too much interpretation, while other speakers were opposed to any restrictions on abortion care altogether.

Just before the committee voted, Sen. Sue Glick, a Republican and author of the bill, urged her colleagues to advance the bill to the full Senate, despite what she called its shortcomings. Glick and several other Republicans acknowledged that “nobody agrees it’s a perfect bill.”

“Am I happy with the bill? Not exactly,” Glick said. “Nor was I happy when it was drafted. This is a very difficult process, and it’s a very difficult issue. It involves some of the most intimate things that could possibly be discussed. I’m asking for support from this committee that we’ll bring it to the floor so we can discuss it in detail, and if it’s the will of the body to kill the bill on the floor — then so be it.”

Sen. Ed Charbonneau, a Republican who voted to advance the bill, said he hoped that input from the full Senate would help make a “bad bill less bad.”

The proposed legislation included exceptions for rape and incest — exceptions that anti-abortion advocates argue might not have been included if not for news that a 10-year-old girl who was sexually assaulted in Ohio became pregnant and traveled to Indiana to terminate the pregnancy.

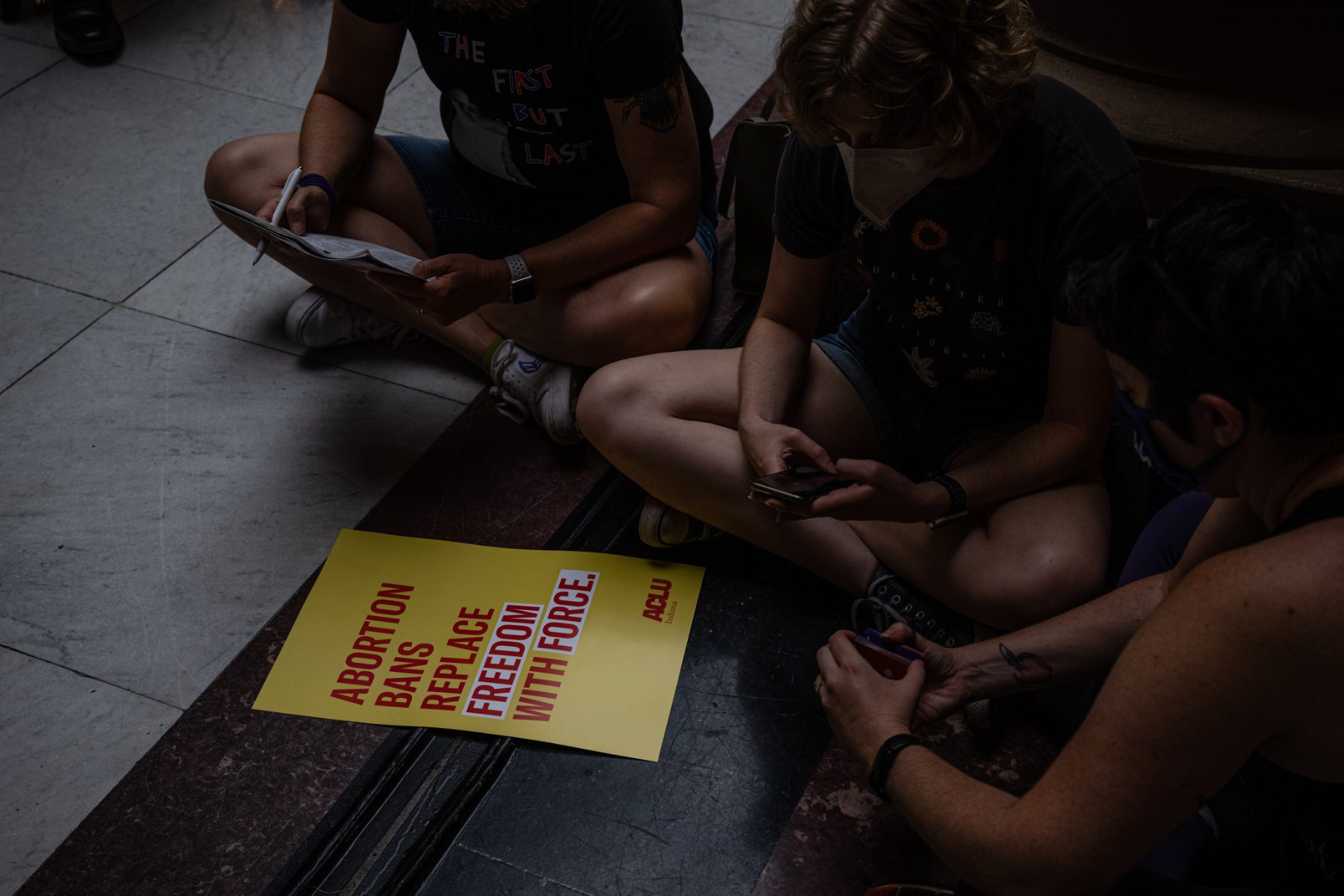

The atmosphere in the Senate chamber was charged: Committee members sat up front, and the senators’ usual seats were filled with members of the public hoping to testify. Every seat in the public gallery was taken, with police stationed at the doors to keep rowdy protestors out and ensure the chamber remained civil. Those in the gallery were told no clapping, no boo-ing, no holding signs during the testimonies. Still, there were many snaps, a few outbursts and the occasional but brief applause. And the steady hum of hundreds of protesters in the lobby, chanting and carrying signs to display in the glass windows at the back of the chamber, provided a backdrop to the entire proceeding.

At one point after concluding public testimony — which included a mix of personal stories and expert witness — Senate Minority Leader Greg Taylor, a Democrat, was brought to tears, recalling his sister’s unplanned pregnancy at 16. Taylor recalled the trauma that his sister went through, and continues to go through, and said he couldn’t fathom forcing other young women to undergo the same.

Many medical professionals testified as well, though their critiques of the bill varied. Some worried that the bill would discourage obstetrician-gynecologists from providing care in rural areas, specifically, out of fear that they will run afoul of the law and be charged with a felony. Others argued that the bill relies too heavily on the “medical judgment” of physicians in determining whether and at what point the life of the mother is at risk and if a fetal anomaly is fatal enough to justify the abortion under the law. Still, some physicians who oppose abortion pushed for more accountability and enforcement requirements in the bill text — insisting that physicians who provide abortions against the law should face criminal consequences in addition to losing their licenses.

Many religious leaders and ministers, overwhelmingly Christian, testified, often quoting the Bible to argue that abortion should be criminalized with no exception on moral grounds. The prospect of eternal damnation was invoked, with senators and witnesses discussing at length who would go to hell and how that is decided. There were, however, a couple religious leaders, including a rabbi, that argued against any infringement on a woman’s autonomy.

Clare Stephens, a registered nurse who testified Tuesday, said she was against the bill because it didn’t go far enough to restrict abortion access in Indiana. Stephens particularly took issue with the language in the bill that allowed for abortion when the fetus was diagnosed with an “irremediable medical condition.” She shared her story: When her mother was four months pregnant with Stephens and her twin sister, doctors diagnosed twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) — a serious prenatal condition in which twins share unequal amounts of the placenta’s blood supply. In the majority of cases, only one baby survives to birth. The doctors encouraged Stephens’s mother to terminate the pregnancy, she said, because the twins had a less than 20 percent chance of survival, and if they did survive would likely have severe handicaps or birth defects.

“Again and again, the doctors pushed and pressured our parents to abort us,” Stephens said in her testimony. “Three times a week, mom went in for an ultrasound and three times a week these doctors would emphasize that it’s not too late to terminate pregnancy.”

Stephens and her twin sister were born at 35 weeks without any complications.

“The doctors got it wrong, and we are not alone,” Stephens said. “I represent thousands. Born with a fetal anomaly or not, don’t our lives have value?”

Danielle Spry, a registered labor and delivery nurse and a mother whose fetus was diagnosed with a fatal fetal anomaly, also testified the day prior that she was against the bill. However, Spry said she believed every woman should have the right to choose. About 18 weeks into her second pregnancy, Spry said, her doctor saw an anomaly on the ultrasound. After further examination, the doctor found that Spry’s fetus had a large hole in her diaphragm, not allowing for lung development, and would certainly suffocate to death at birth.

“My husband and I knew that as much as we loved her and as much as we wanted to bring her home, allowing her to suffer was not an option,” Spry said. “We ended our pregnancy at 19 weeks and six days, which was the last day in Indiana we could legally have the procedure. … I cannot even fathom the trauma if I didn’t have that choice and was forced to carry her to term, fielding questions from strangers about my growing belly.”

The Indiana House is expected to take up the anti-abortion measure next week. If the legislation passes, then it will take effect in September.