With these 37 words in June 1972, Congress ushered in a sweeping new era in the struggle for gender equality in America: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 marks its 50th anniversary this month. The law was born at the dawning of the modern feminist movement, as women pushed for their full participation in democracy and society.

The 19th will mark this milestone as the theme of our annual summit, focused on the legacy of Title IX to promote gender equity in higher education, athletics, the workforce and beyond.

This week, I spoke to a pair of women whose work focuses on these issues. I’m also bringing you a sneak peek of our summit with part of my interview with Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a former educator focused on policy aimed at addressing gender and racial inequities. (For our first ever hybrid summit, we’re also talking to champion basketball coach Dawn Staley, paralympic track and field athlete Scout Bassett, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, and more.)

Gender equality is woven into all the major issues in our politics now: the economy, voting rights, gun reform, and the future of democracy, reproductive access and LGBTQ rights. Fifty years after Title IX’s passage, what work is left undone, and what lessons does the legislation hold for how policy can help level the playing field?

“Many people are unaware of how revolutionary the changes in gender relations and the changes in women’s opportunities have been over the last 50 years,” said Nancy L. Cohen, president of the Gender Equity Policy Institute. “The anniversary allows us to reflect on the work that’s needed to make and institutionalize change, to protect it and not become complacent.”

In 1972, women were demanding change. The birth control pill had been invented just a decade earlier. Abortion had not yet been deemed a constitutional right by the Supreme Court; that would come the next year with its decision in Roe v. Wade. The Fair Credit Opportunity Act, which allowed women to open credit cards and get mortgages in their own names, was two years away.

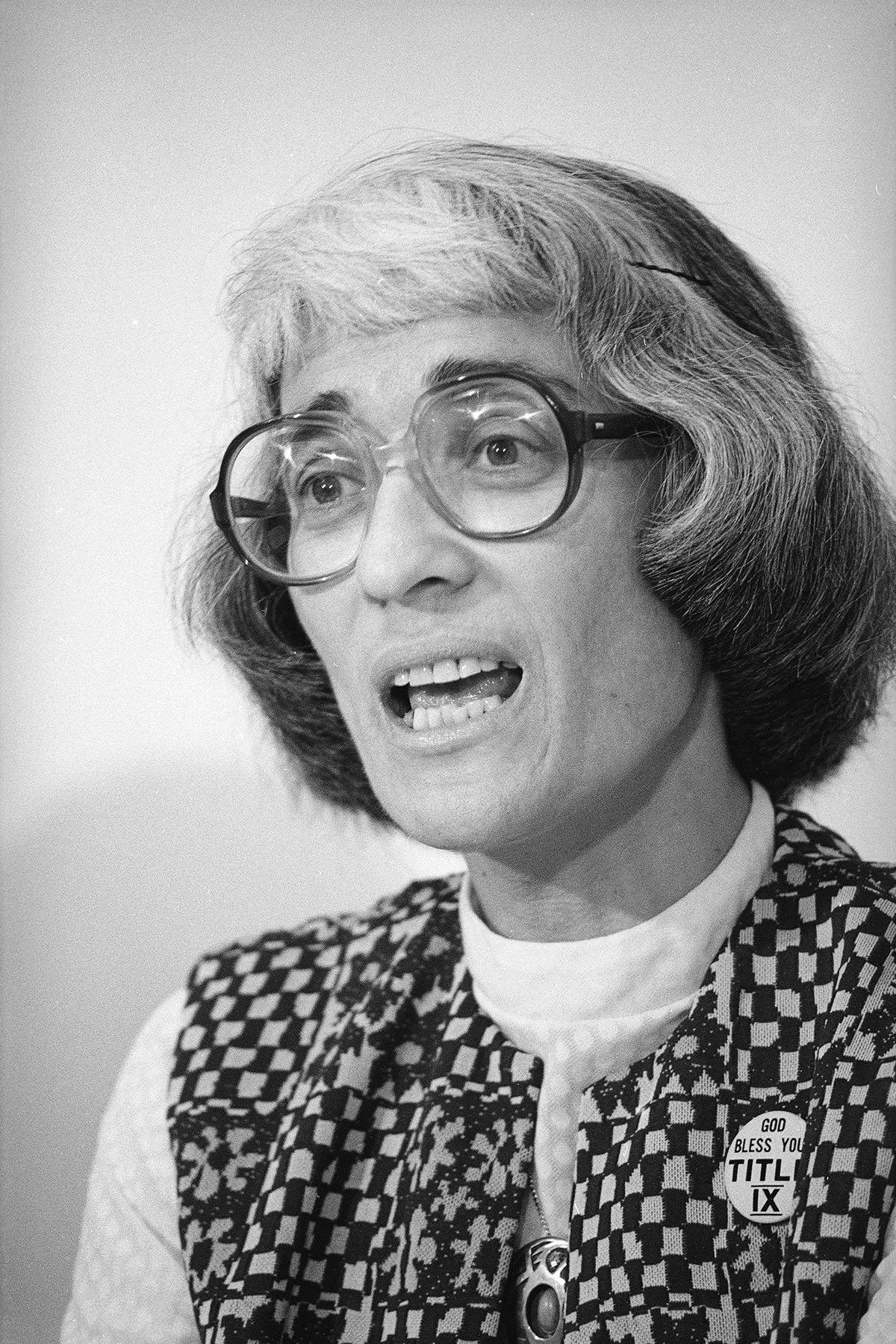

Bernice Sandler, called “the Godmother of Title IX,” had been denied full-time teaching positions at the University of Maryland. Her unequal treatment spurred her into action, collecting other stories from women in academia. Sandler shared their stories with Congress and the Department of Labor, creating one of the biggest compilations of documentation of sex discrimination and putting the issue into the Congressional Record. Sandler’s work sparked hearings that led to Title IX — the first hearings ever in Congress on sex discrimination in education.

Title IX applies to public and private educational institutions that receive federal funds. The most visible beneficiary of the legislation is women’s athletics. Title IX doesn’t require institutions to offer identical sports, only an equal opportunity to play. Schools are required to award athletic scholarships proportional to their participation, and the statute requires equal treatment in areas including equipment and supplies, scheduling of games and practice items, locker rooms, facilities, coaching, and recruitment.

Cohen was a high school lacrosse player who was recruited to play in college in the wake of Title IX. She said she turned out not to be very good — but because of the law, she had a chance to try and to find out.

“I’m old enough to be part of the first generation that played sports competitively,” Cohen said. “I was young, so I wasn’t aware that wasn’t available before me. When change happens when you’re at a particular age, you may not see the change. The fact that schools are required to treat women equally to men has made a major impact.”

Cohen said it would be hard to imagine women graduating from college and graduate school at the levels they do today had it not been for Title IX. And yet, she said, the strides women have made may have allowed later generations to take that progress for granted.

“There is a tendency to see gender equality as a lower priority, as something maybe you get to when the bigger, more important things are taken care of,” Cohen said. “A movement for change requires a lot of different methods and a lot of different groups of people pushing from different directions. But ultimately, political power and the power to make policy and make law is essential to advancing equality, accelerating equity and institutionalizing it in a way that really benefits people.”

Title IX stands as a clear example of the power of policy to impact gender equity, Warren told me. Our conversation aired in full on Wednesday at The 19th’s annual summit.

“Policy is how we make real change,” Warren said. “Title IX is when we begin to talk as a whole country and say, ‘We’ve got a lot of women who are smart and thoughtful and engaging, and we want to hear from them … And this is a part of how we make that happen.’ You do good policy, you make big differences.”

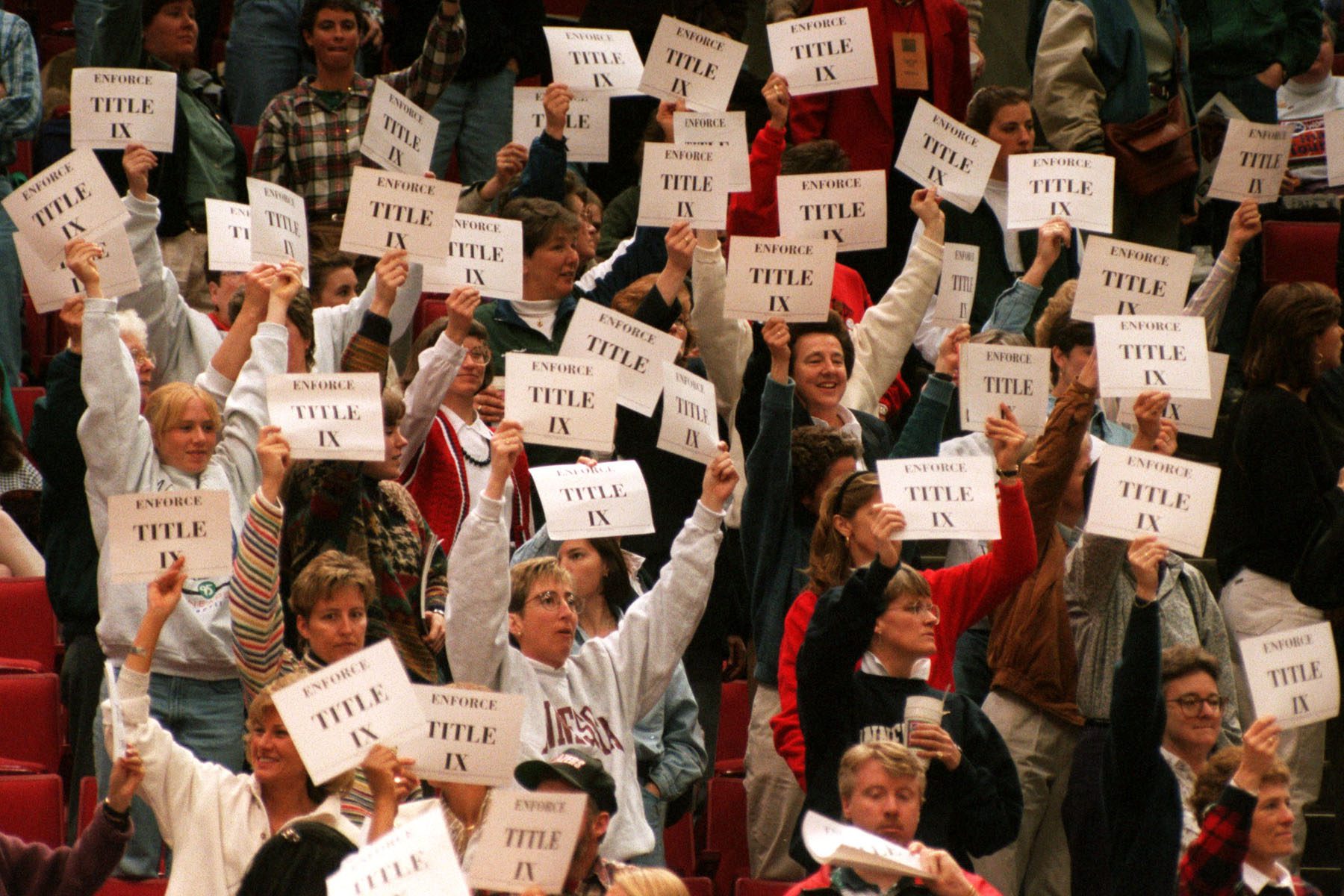

The progress and pitfalls in the years since the passage of Title IX are on full display today in sports.

Elizabeth Tang, lead author of a new report from the National Women’s Law Center, “Title IX at 50,” said the advances made in gender equity since the landmark legislation have been met with backlash — from people attempting to discredit sexual assault survivors and those attacking the rights of transgender youth.

“When people are in positions of power and they see the tide changing, they want to do as much as possible to hold onto that power,” Tang said. “Title IX was intended to be a very broad law to provide broad protections. It’s a very powerful tool, and we want to see policymakers take advantage of how broad this tool is.”

The report offers policy recommendations to further the gains begun with Title IX in a variety of areas: sexual harassment, pregnant and parenting students, discriminatory discipline by race and gender, sex-segregated education, support for Title IX coordinators in school districts and higher education institutions. It doesn’t take new law, they say — it’s all in the original Title IX.

“We understand policy change does take time, and we’re recommending steps everyone can take,” Tang said, adding that states and local jurisdictions can also act, that President Joe Biden can take executive action, and that the Department of Education can offer regulation and guidance or conduct more enforcement actions.

“Every type of policymaker, every institution has a role to play in combating sex discrimination and promoting gender equity,” Tang said.

Half a century ago, Congress helped usher in a freer, fairer country for Americans of all genders, pushed by many women who raised their voices to reject their second-class citizenship. How will this generation of lawmakers and the electorate defend these hard-won rights, for now and for the future? How can they be expanded? Join us next week as we discuss the path forward with politicians, athletes, activists and you.