JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Herman Miller never asks his patients why they come to his office, but sometimes they tell him anyway. They just need to say it out loud.

There are people who desperately wanted a child and then found out at 16 weeks pregnant that they would give birth to a baby with major health problems — at least one, he recalls, who would have been born without functioning lungs. There are those who had a plan, a partner who would raise a child with them, before they were left on their own. There are patients who drove six hours to get here, who couldn’t get here sooner because rent was due or a kid fell sick. Some just needed a few extra weeks to pull together a few hundred dollars.

And there are the children — 13- or 14-year-olds who didn’t know how to tell their parents. There are even younger kids who didn’t realize they were pregnant because they had never had regular periods before. The youngest patient Miller treated was 11.

Miller, a 75-year-old OB/GYN, sees patients two to three days a week here at A Woman’s Choice, the abortion clinic where he’s worked since 2001. He’s the only doctor at this clinic who provides abortions all the way up to 20 weeks of pregnancy, a medical service that is currently legal in most of the country but that, due to stigma and the threats of violence against physicians, fewer and fewer doctors provide.

Anti-abortion protesters have picketed his house. After Miller’s wife died, a deliveryman once asked him if it was punishment for the work Miller does.

But as a physician, he says, this is his duty.

“People want to judge me because I do abortions, and they’re talking about morality. But as far as I’m concerned, morality cannot be legislated,” he said. “I look at every patient as someone who has a problem or a concern or a reason that, if I can help, that’s what I’m going to do.”

On July 1, Florida will begin enforcing a law banning abortions for people past 15 weeks of pregnancy. The ban, which has no exceptions for rape or incest, has been framed by its backers as a “moderate” compromise. The vast majority of abortions take place within the first trimester, which ends at 12 weeks, they note. The law is less stringent than the six-week bans and total prohibitions being passed across the country in anticipation of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed the right to an abortion, later this summer.

Still, the 15-week ban, which has no medical rationale as a particular endpoint for access, represents a tremendous shift in Florida. The ripple effects could extend far outside of the state’s borders.

Currently, abortions are legal up until 24 weeks in the state, which has more than 60 clinics. If, as expected, Roe is overturned, Florida will become a critical access point. The state, particularly its northeastern region with its cluster of clinics, will offer the most viable option for finding a safe, legal abortion for places such as South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana — all of which are poised to ban abortions, either entirely or for patients beyond six weeks of pregnancy.

-

The Latest:

Here in Jacksonville, only an hour from the Georgia border, patients already cross over frequently from other states to get care. Staff at A Woman’s Choice are anticipating the number of out-of-state patients coming here to surge in the coming months. And they expect that, as people travel farther for care, more will show up later into pregnancy — making a 15-week deadline that much harder to meet.

With the end of Roe in sight, anti-abortion activists are energized, pressing Gov. Ron DeSantis to go further in restricting abortion. So far, the governor — a rising star in the Republican Party who is widely believed to be eyeing a 2024 presidential run — has been noncommittal. Incoming leaders in the state legislature have indicated openness to passing a total ban on the procedure when they reconvene next spring.

Miller believes it’s only a matter of time before abortion is inaccessible in Florida.

“I’m scared of the 15-week ban. But it’s not my greatest fear,” he said. “My biggest fear is the fact that, if they overturn Roe v. Wade, the first thing DeSantis would do is try to ban abortion here.”

While the conversation at the capital may be about stricter bans, staffers at abortion clinics are thinking about something more immediate: the patients who will be cut off from care in a matter of weeks.

“It’s almost like a slap in the face, that we’re saying out loud, ‘We don’t trust women,’” said Kelly Flynn, CEO of A Woman’s Choice. “And then I just question, why doesn’t everyone think about the person? The woman, the person that’s pregnant? Why doesn’t her life matter? Why are we putting that person who’s already been here for anywhere from 15 to 50 years, and making her irrelevant?”

Supporters of the 15-week ban have argued that only a small number of people will be affected. The state’s health department data shows that in 2021, when it recorded 79,817 abortions, slightly over 6 percent of that total — 4,850 people — were for people in their second trimester of pregnancy. The state doesn’t specifically collect data on abortions performed for people at 15 weeks and later.

But the number of abortions performed in the second trimester appears to be growing, at least at A Woman’s Choice. Terry Salas Merritt, a consultant who has worked with the clinic for six years, estimated that last year 10 percent of the patients they saw sought abortions in the second trimester. Since January, the percentage of people seeking abortions after 12 weeks has doubled.

Now, close to 1 in 5 of the clinic’s patients are getting abortions in the second trimester. A significant chunk of those are past 15 weeks, per Flynn — patients who would no longer be able to get an abortion once the new law takes effect. Neither Flynn nor Merritt can fully explain why there has been an uptick, but both suspect that people are having more trouble pulling together the money for an abortion, which can be hundreds of dollars at a minimum.

“For everything in the universe, costs are higher: for gas, for child care, for anything and everything. And rents are going up,” Merritt said. “Any disposable income that you had for emergencies — that got depleted. So it takes more time.”

-

More abortion coverage

- Many states are bracing for a post-Roe world. In Oklahoma, it’s practically arrived.

- With abortion rights in limbo, conservative lawmakers are eyeing restrictions on IUDs and Plan B

- ‘This changes everything’: Moms wonder what an end to Roe could mean for their families and future

While many of those patients are locally based, others have been traveling hundreds of miles to get to A Woman’s Choice. It’s already a regional destination and one that takes time and money to reach. Patients come here from Georgia, Louisiana and South Carolina. When, last September, Texas began enforcing its six-week abortion ban, a handful of patients made the trek to Florida.

If Roe is overturned, those numbers will surge. Alabama has an abortion ban on its books that predates 1973. Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana have passed trigger laws that will ban abortion almost entirely. Georgia has a six-week ban on its books that would likely soon be enforced. For patients in each of those states, Florida — with its extensive clinic options — will represent one of the safest and closest options. The next best are North Carolina, seven hours to Jacksonville’s north, or, for some Texans and most Oklahomans, clinics in Kansas.

But patients who need to travel will likely be later in pregnancy by the time they can get an abortion appointment, noted Elizabeth Nash, who tracks state policy for the Guttmacher Institute. Texas has shown that. In the weeks and months following its six-week abortion ban, the heightened expense of traveling hundreds of miles for care — combined with weeks-long wait times at clinics that didn’t have the capacity to immediately see all the patients calling for appointments — meant more and more patients were pushed into their second trimesters before they could get an abortion, Nash said.

That means the 15-week ban is not a hypothetical concern, she said. It’s a real barrier that could make Florida — otherwise the most viable option — impossible for some.

”If you think that a 15-week ban is some kind of compromise, that’s a mistaken idea,” Nash said. “Because what abortion restrictions have done, and the stigma on abortion has done, is create delays, which just push people later into pregnancy before they can access care.”

That’s one of Flynn’s great fears: Someone will make an appointment. For weeks, they will raise the money, perhaps coordinating child care and time off from work to make it for two visits at the clinic — the first for a medical consult, and the second, 24 hours later per state law, for the appointment. They will drive 12 hours from the Texas-Louisiana border to Jacksonville. And by the time they get there and undergo the ultrasound to date their pregnancy, they’ll be too late.

“It could only be by a day or two, but if it’s anything past 15 weeks, legally, we won’t be allowed to see the patient,” she said. “That’s going to be traumatic for this person, because now they’ve traveled from Texas to Florida and then now say, ‘OK, now we have to go from Florida to North Carolina.’”

Flynn is working to hire more staff so that the clinic is not overwhelmed when Roe is overturned. A Woman’s Choice is trying to build out capacity in other ways, too, creating networks of volunteers who can house people who will travel from out of state for an abortion, and setting up carpools and ride-shares so they don’t need to raise as much money for gas.

Local abortion funds are taking similar steps. Julia DeSangles, the co-executive director for Florida Access Network, said her fund is trying to forge relationships with organizations in other states. They’re preparing to send Floridians past 15 weeks to North Carolina, to Washington, D.C., and even to Colorado. And they’re raising money so that they can support the anticipated surge in patients relying on Florida for care.

But it’s difficult to plan. Florida Access Network has already struggled to meet patients’ needs. Last year, the total amount of money people sought from them approached half a million dollars, DeSangles said. They were able to provide only a fraction of that — close to $40,000. And at the clinic, Flynn said, it’s tough to estimate just how many new people to hire, when they live in fear of a six-week or total ban passing in less than a year.

“So many people aren’t going to be able to get the care they need, and are going to have to give birth or find other means to manage their pregnancies,” DeSangles said. “It’s really tragic and frustrating that we’re here and that it’s come to this. Right now it just feels so hard.”

A Woman’s Choice and other abortion clinics in the state have found themselves on the front lines of the Republican Party’s decades-long campaign to restrict abortion access. And in Florida, the nation will see one of the most potent tests of whether Republicans can, in fact, find a middle ground between restrictions and total bans.

“We’ve seen for months Florida Republicans not wanting to talk about this,” said Mary Ziegler, an abortion law historian who previously worked at Florida State University. “The fight within the caucus — it’s something we just don’t know how it’s going to go yet.”

Historically, stringent abortion restrictions haven’t been a sure political winner in Florida. As recently as a year ago, an effort to ban abortions at 20 weeks of pregnancy couldn’t even make it out of a committee hearing. Abortion is currently protected in the state: In 1989, the state’s supreme court ruled that Florida’s constitution guaranteed the right to an abortion, an extension of its right to privacy.

Even now, restrictions don’t appear popular. A poll conducted in May from Florida Atlantic University found that about 66.7 percent of Floridians believed abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Just under half of that — 31.8 percent of all respondents — said they wanted abortion legal in all cases. Polling from the University of North Florida released in February found that 57 percent of registered voters did not support the state’s new 15-week ban, which passed the legislature in March and was signed into law in mid-April.

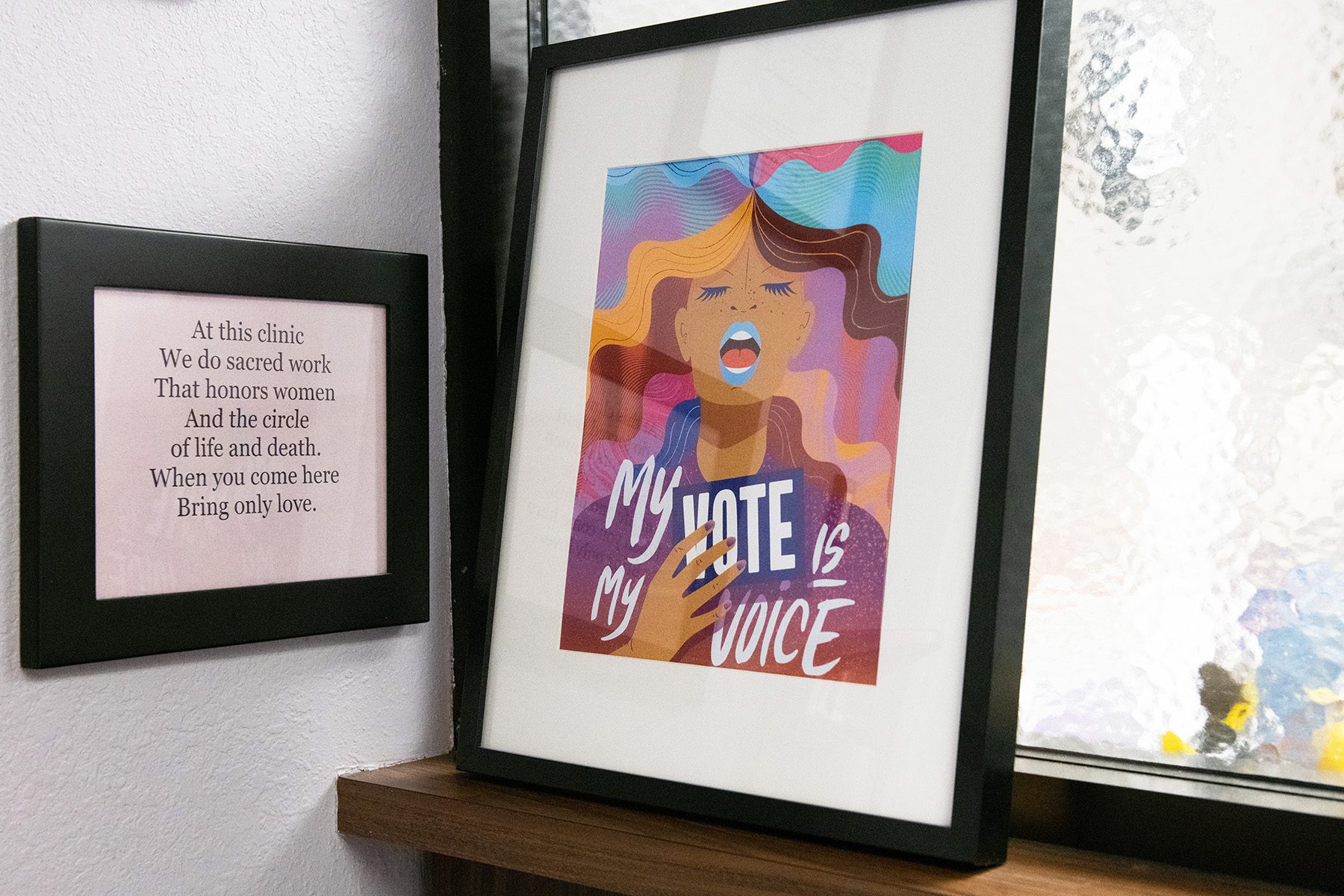

But momentum may be shifting in favor of the state’s anti-abortion movement. It’s visible just outside A Woman’s Choice: Ever since the Supreme Court leak, clinic staff say, the protesters have been emboldened. They’re louder, and there are more of them. As early as 8 a.m. on days that patients are coming for appointments, protesters arrive with signs, jeering at employees and patients, snapping photos of the license plates that enter the parking lot.

Flynn started hiring off-duty police officers to monitor the situation. Now, she has stopped hiring the officers, but the police presence remains. The Jacksonville sheriff has begun regularly sending at least one official on patient days.

Both nationally and in Florida, abortion rights opponents have found a new bolt of energy. And it comes just as DeSantis’ political aspirations are likely to push him in favor of backing more restrictions, noted Michael Binder, a political science professor and pollster at the University of North Florida who has tracked public opinion regarding the state’s 15-week ban. While abortion bans aren’t popular across the state, they are uniformly backed by Florida Republicans.

If DeSantis hopes to be president, he will face pressure from Republican primary voters across the country to show he has fought against abortion access, Binder said. While both liberal and conservative Democrats oppose abortion restrictions, about 60 percent of Republican-leaning voters believe abortion should be illegal in most or all cases, per data compiled by the Pew Research Center. Conservative Republicans are more likely to back bans: 72 percent believe abortion should be illegal in most or all cases.

“If you look at the things he’s been doing this legislative cycle and in the previous legislative cycle, he’s been geared and targeted toward 2024,” Binder said.

When asked about any plans for future abortion bans, DeSantis spokeswoman Christina Pushaw directed The 19th to previous remarks about the 15-week ban specifically and stated that the governor “has always been pro-life.”

That, Ziegler said, reflects the politically tenuous situation Florida Republicans currently occupy.

“There’s been a lot of studious avoidance, and I think ambivalence and anxiety that we’ve seen from the governor — I think because there’s a sense that on the one hand, he wants to be president and wants to convince the anti-abortion movement that he’s a reliable ally, and on the other hand he’s probably seen the polls everyone else has,” Ziegler said.

But that could change by next year. DeSantis is up for reelection this fall. But after November, the next election on his horizon likely won’t be statewide — it will be the Republican presidential primary.

With that in mind, Binder said, he fully expects the governor and legislature to seriously consider a law banning abortions at six weeks of pregnancy, if not altogether.

Andrew Shirvell, who runs the anti-abortion lobbying group Florida Voice for the Unborn, is hoping for a six-week ban, at a very minimum. Last fall, Shirvell pushed for Florida to follow Texas’ lead and enact a six-week abortion ban that relied on civil litigation, not criminal punishment. Legislative leadership instead rallied instead around the 15-week ban.

Now, weeks after the Supreme Court’s draft opinion overturning Roe leaked, he’s frustrated. Voice for the Unborn has been calling on DeSantis to launch a special legislative session to immediately pass a total abortion ban. So far, he’s heard nothing. But he’s still optimistic that the legislature’s incoming leadership will support at the very least a six-week ban on abortion. He’s already noticed a change in how lawmakers even talk about the policy — the incoming Senate president just acknowledged to Politico, for instance, that “there’s always a chance” the legislature could pass a total abortion ban.

“This is the first time they’re talking about this near-total ban on abortions here in Florida, rather than saying, ‘No comment,’ or ‘We have to wait and see,’” he said.

Even that is a rhetorical shift, but a subtle one, Ziegler noted, and not necessarily translatable into full-throated support for an abortion ban.

But for now, Shirvell’s organization will keep the pressure on for a ban to be passed either this summer or — at the latest — next year. They’re planning phone-call and letter-writing campaigns, political canvassing, and sit-ins, for a start. The mission is now more important than ever, he said. Unless the legislature does something, he knows the state will become the only place people across the region will be able to access abortion.

“We’re seeing movement in the right direction and we’re going to push until we get what we want,” he said. “We’ll create the pressure necessary to make them so uncomfortable they’d never think about delaying it — or they’ll regret delaying it. The dynamics have really changed with Roe falling.”

Planned Parenthood has sued to stop the 15-week ban from going into effect, arguing that it violates the state supreme court’s ruling protecting abortion rights. The lawsuit was filed in a state circuit court, but is expected to be appealed to Florida’s state supreme court — which has shifted to the right in recent years. Three of its seven members were appointed by DeSantis; a fourth was appointed by former Gov. Rick Scott, now a Republican senator.

Florida’s political observers and abortion rights experts suspect that, when the time comes, the state supreme court will use a 15-week ban case to overturn Florida’s abortion rights guarantee.

That future is hard to visualize from inside A Woman’s Choice. Miller is one of three physicians who works here and the only one who goes up to 20 weeks. One other sees patients up to 16 weeks, and the third goes to 12. On clinic days, Miller sees anywhere between a dozen and 16 patients.

Some come from Miami, almost six hours south by car — they can’t find an appointment closer to home with a doctor who works into the second trimester. Some are from South Carolina. The biggest group are between the ages of 19 and 25. After that, it’s patients who are 15 and younger. A handful are patients whose doctors referred them to him, because of a late-diagnosed problem with how the fetus has developed.

Miller is thinking about how the 15-week ban will affect all of them. And beyond that, he’s worried about what happens if and when Florida goes further.

Some patients, he hopes, will be able to travel out of state, to North Carolina, or to New York or Illinois. But others won’t be able to afford the journey, he said. Others won’t have the connections or support from the health care system.

Those, he worries, are among the ones who will die: some from attempting to unsafely induce their own abortion, and still others simply from the risk of giving birth. He worries most, he said, about the people who look like him — Black people, who in America have persistently higher rates of pregnancy-related death than White people.

“What are you going to do about them? If you don’t see them until after 15 weeks? What are you going to do for them?” he asked. “Nothing.”