Early Friday, emails flooded Dr. Jen Kerns’ inbox. In the hours after Roe v. Wade was overturned, doctors and patients turned to providers in states where abortion is still legal, like Kerns, who performs abortions in San Francisco and Kansas, asking for appointments.

These partnerships between providers were happening already as abortion access started to shrink across the country, but now the work has taken on a “slightly more frenzied tone to it, knowing that people are going to have to jump through multiple hoops in order to get out of their state to access care,” Kerns said.

On Friday, when the Supreme Court issued its decision overturning Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case that granted the federal right to an abortion, it deepened fissures across the country. There are the states where legal abortion access remains and there are thirteen states with trigger laws that will quickly ban abortions now that Roe is overturned — in some cases the procedure has already been banned. And another 13 states are trying to provide as much care as they can while they wait to see what potential restrictions may come.

In this post-Roe reality, states where abortion access is still legal serve as critical access points. Kerns said abortion providers are doing all they can to move patients from state to state for care. Networks are forming: Of clinics referring patients to other clinics, and of physicians calling their colleagues for help as clinics brace for an onslaught of patients.

Clinic staff, operators and providers at abortion care facilities in places where abortion access is secure are planning how to best serve a new influx of patients. At the same time as they try to put plans in place, many of these clinics are strategizing on how to shift quickly should the situation in their state change overnight. In the states where abortion access remains, or remains for the time being, clinics now must figure out how to serve the deluge of patients soon to be coming their way as more and more states limit or ban access in the coming weeks and months.

Zack Gingrich-Gaylord, the spokesperson for Trust Women, which operates an abortion clinic in Wichita, Kansas, said calls started to come in as soon as Roe fell. People still in the lobbies of clinics where abortion services had to cease immediately after the ruling were calling Trust Women’s Kansas clinic for help. In Kansas, abortion is still legal, but voters will decide in August whether or not the state should continue to guarantee access under its constitution.

The state is treating clients in the middle of what Gingrich-Gaylord calls an “abortion desert.” The state’s immediate surrounding neighbors of Missouri, Oklahoma and Arkansas all had “trigger bans” on the books set to ban abortion statewide, in all forms, as soon as Roe fell. “We already have a paucity of access, but now all the states that are going to go dark are in our neighborhood,” Gingrich-Gaylord said.

-

More abortion coverage

- Patients sat in abortion clinic waiting rooms as Roe fell. They all had to be turned away.

- The Biden administration just hinted at how it could protect access to medication abortion

- From marriage equality to interracial marriage, Supreme Court conservatives appear divided on handling civil rights after Roe decision

Serving the degree of need they are expecting is going to be a logistical impossibility.

“Even if we were to open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week — there are not enough appointments,” Gingrich-Gaylord said.

Clinics are putting plans in motion to expand their services as much as they can. Dr. Kristina Tocce, the vice president and medical director of Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains, which operates in Colorado, New Mexico and Las Vegas, said her network is now focusing on expansion — for different clinics, this can mean new facilities, increased hours or new investments in telemedicine.

“We have revisited all of the plans we’ve had and we have put certain projects on a fast-forward mode,” Tocce said. We have “increasing hours, increased days of service, increased providers and staff, utilizing telemedicine to its fullest potential … we have all those plans in place right now.”

In Washington state, Mercedes Sanchez, the communications director of the Cedar River Clinics, said her clinics are also planning on expanding.They have been preparing for the post-Roe landscape “since the 2016 election — and then COVID had us expediting some of our plans,” she said.

Right now, Sanchez said, Cedar Rivers is focused on finding additional funding to support their clinics so they can hire more staff and serve more patients. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that Washington state will see a 385 percent increase in patients — a number based solely on the patients who may come from immediate surrounding states.

Cedar Rivers also recently reopened their clinic in Yakima, in rural Eastern Washington, after hearing about patients facing long wait times for abortions. Still, despite the planning, there are unanswered questions.

“It’s all still so unknown,” Sanchez said. “We are working on various strategies on how we can use telemedicine in our state, how we can balance seeing all the people who come to us. Yes, it will be a challenge. If the prediction even comes close to coming true, we will definitely need more help financially to continue on with our plan to hire new staff.”

Melissa Grant, the chief operating officer of Carafem, a network of abortion clinics operating in 16 states, says that she anticipates that telehealth appointments, through which providers can issue medication abortions, will help relieve some of this burden from the influx of people needing care in their clinics.

“If patients in blue states can be seen at home through discrete telemedicine appointments in the comfort of their own homes, that will take some of the pressure off of health centers and give [patients from out of state] the ability to be seen more quickly.”

But Grant acknowledges “that’s not an option for everyone.” Per regulation from the Food and Drug Administration, medication abortion can be utilized for approximately up to 10 weeks of pregnancy. In Indiana and Texas, state laws exist banning the use of medication abortion past a certain point in early pregnancy. Nineteen states have regulations about a physician needing to be present when the medication is administered, thus preventing the use of telemedicine for medication abortion in those places. “

“So we’ll keep trying to be flexible and make those appointments available,” Grant said.

On a national level, Grant says that Carafem and other abortion providers will have to “step up” to make sure that information about abortion access is readily available to all who need it. On top of that, she says her clinics in places with access need to prepare for all the new clients they are about to serve by creating efficient operational systems.

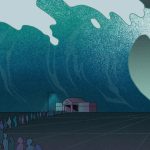

“We will see a wave of clients that will overload our northern clinics, and so we need more flexibility — we’re ready for that too. We’re streamlining our systems, we have more staff on call, we’re having more flexible hours. As much as we can, we’re planning.”

Part of this planning also includes creating new systems and tactics to quickly connect patients in places with restricted access to other clinics. Dr. Katherine Farris is the chief medical officer of Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, which operates health centers providing abortion care in North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia. Farris is busy working with her team to put in place “all the pieces we’ve been building for months” to ensure that patients in South Carolina — which is poised to quickly implement a six-week abortion ban now that Roe is overturned — can most easily access care in Virginia and North Carolina.

“We’re trying to help South Carolina patients as soon as possible,” Farris said. “Soon we’re going to be under a six-week abortion ban and we’re helping people get in as early as possible.”

Planned Parenthood South Atlantic is going to implement a consolidated system so that regardless of what state their patients are in, the group can serve as “navigators” to help patients access the care they need. Under this system, wherever a patient is seen, clinic staff in that state can either help them proceed with any available care, make appointments or provide referrals for care that may only be accessible in another state. Because of a wide network of both Planned Parenthood health centers and independent abortion clinics in North Carolina, the group is well-equipped to easily connect patients in states without access. The goal is to take the onus off of patients by connecting them with practitioners who can perform the maximum number of allowable services on-site and then connecting them to the care they may need next.

For now, Farris said that she feels providers should be as clear as they can in communicating with patients. “It’s hard to give a clear message, so the only clear message we can send is that we will help you if you need us. We will help you and get you the care you need whether you’re in North Carolina or Virginia, or whether you’re in South Carolina and need to get to a neighboring state.”

But the shifting landscape means that even new plans to accommodate the influx of patients can change overnight.

The future of abortion access in Florida is about to shrink: A ban on the procedure after 15 weeks gestational age will go into effect at the end of next week, July 1. Particularly for patients in Southern states where abortion care is severely limited, the state is one of the last access points for hundreds of miles.

Kelly Flynn, the president and CEO of A Woman’s Choice in Jacksonville, said her clinic is “expecting to see patients from neighboring states and we’ll do our best to handle what we can one patient at a time,” Flynn said.

Flynn said she is in the process of developing a program to partner with people who can help transport patients to other states, likely North Carolina, who are seeking abortions after the 15-week ban goes into effect. The clinic has also revisited plans to expand to North Carolina, where abortion care is still protected.

“We are going to do what we can to keep our doors open,” Flynn said.