When it came down to it, Rick Colby called on his spirituality in deciding how to support his transgender child, Ashton.

It wasn’t a guarantee. Colby had dedicated his life to Republican politics, starting in 1984 on the field campaign to reelect Ronald Reagan. Reagan and the Republican Party with him and in the decades following would push anti-LGBTQ+ policies. But Colby’s Methodist church by comparison preached inclusivity and empathy, a message that conflicted with what he was hearing from Republicans.

Colby went with Ashton to his first endocrinologist appointment. He held Ashton’s hand the following year as Ashton awoke from gender-affirming top surgery.

“You know, as a parent, you want to protect your child from the nastiness of the world,” Colby said. “I was so relieved as a parent that he was being accepted. And it was just wonderful.”

Survey after survey show that Americans support LGBTQ+ equality, and Republicans are no exception. Still, Republican-dominated states have seen a blitz of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation since 2020, particularly anti-transgender bills. That dissonance — between the reality of the electorate and the priorities of Republican lawmakers — may seem counterintuitive to many.

Randall Balmer, a Dartmouth professor who was raised evangelical, has spent much of his career researching those kinds of contradictions. His book, “Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of Religious Right” traces the rise of the evangelical voting bloc from nonexistent in the 1960s to the single most important interest group for any Republican candidate in the 1980s. In a conversation with The 19th, Balmer said that rise was driving Republican support for anti-trans legislation now.

“They have an interest in keeping the base riled up about one thing or another, and when one issue fades, as with same-sex relationships and same-sex marriage, they’ve got to find something else,” Balmer said. “It’s almost frantic.”

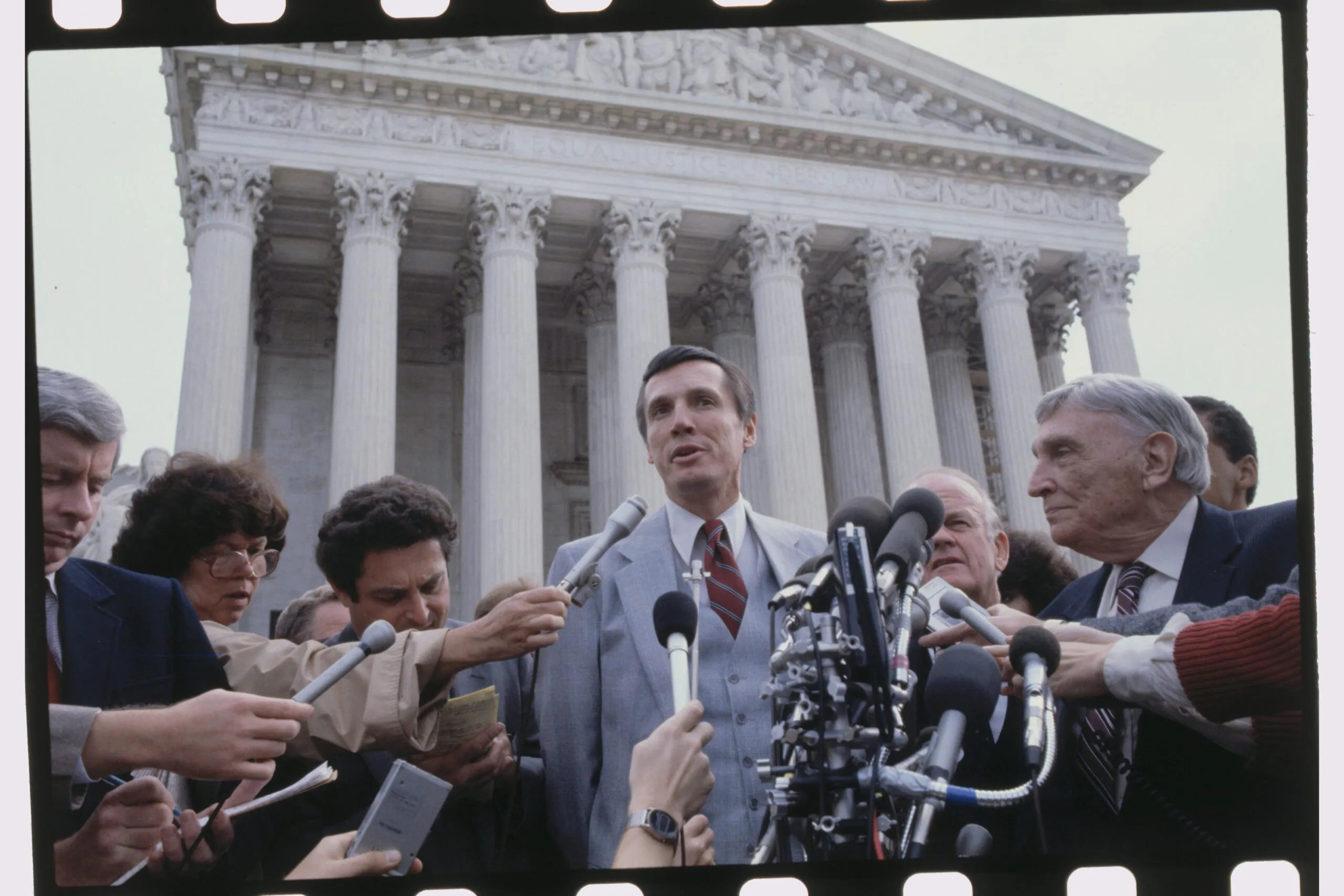

While many people believe that abortion was the issue that first galvanized evangelicals to the polls in the 1980s, Balmer points to a different issue. Paul Weyrich, an evangelical Christian who helped initially organize the “religious right,” had been testing out issues that would drive other evangelicals to the polls in the 1970s, Balmer says. Weyrich found it in Bob Jones University, a religious institution that was facing the loss of its tax-exempt status for refusing to racially integrate.

Weyrich’s strategy worked. In 1980, evangelicals – a group of denominations separate from mainline churches like Colby’s – flocked to the polls to back what had been billed as the freedom of a religious school to operate without government interference. Reagan backed Bob Jones University, with two-thirds of the evangelical vote, denied President Jimmy Carter, a Democrat and an evangelical himself, a second term. It cemented White evangelicals as the key ingredient to Republican wins.

Any Republican who wanted to cross the finish line would have to kneel at the feet of the evangelical base, Balmer says. Decades later, Donald Trump would initially campaign on welcoming LGBTQ+ people into his Republican platform, only to later adopt the ideology of the far-right evangelical base he needed to win.

While Trump appeared to start out a social moderate, far-right evangelical policies increasingly dominated his agenda. On the campaign trail, Trump briefly vowed to be an ally to queer Americans. In office, his administration made so many policy moves against LGBTQ+ Americans that advocacy organizations branded his leadership “The Discrimination Administration.”

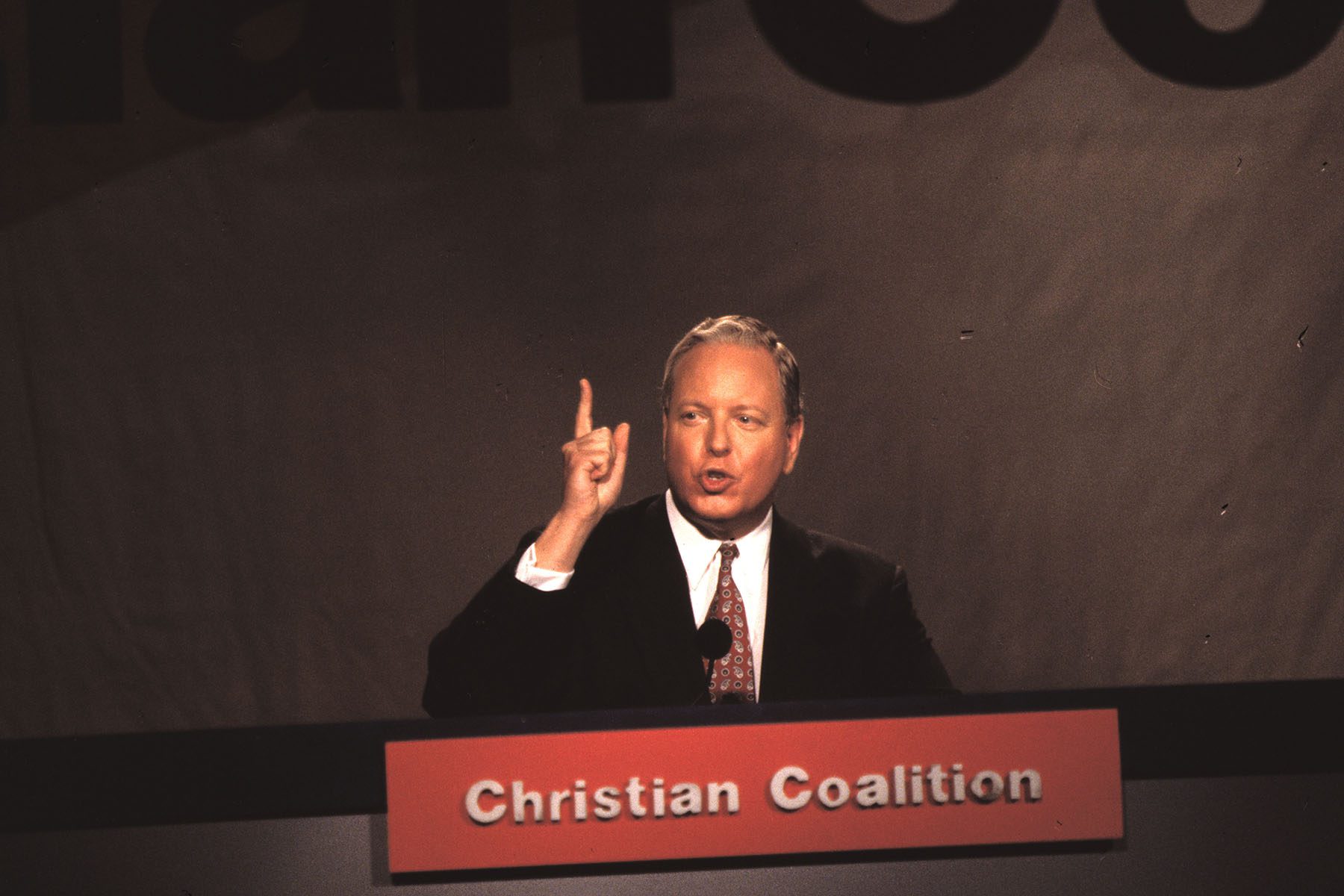

The religious right’s fixation on “social issues” — abortion, religious-based education, LGBTQ+ rights — served two purposes. In addition to keeping evangelicals a cohesive voting unit, they also formed an ideological bedrock for the religious right. Before Weyrich died, he argued that conservatives should be fighting to return to family structures of the 1950s, a goal that has been picked up by leaders after him.

In his book “The Next Conservatism,” Weyrich wrote that the goal was to weed out “cultural Marxism,” and “restore a non-ideological American republic, which is what we had up until the wretched 1960s,” when women and Black and LGBTQ+ Americans pushed for and won greater rights.

After Reagan’s 1980 victory, Weyrich would continue to test issue after issue to keep evangelicals voting, including abortion. This idealized rewind to 1950s America would systematically challenge the basic rights gained by Black Americans, LGBTQ+ people and those with disabilities.

“As they were searching for different issues, I think they understood that any issue that had some sort of connection to sexuality or sexual behavior was going to work for them,” Balmer told The 19th.

The first issue was “sodomy laws,” which aimed to make gay sex illegal. The Supreme Court overruled the last of them in 2003 in Lawrence v. Texas. Next came marriage equality, which was granted nationwide by the Supreme Court’s Obergefell ruling in 2015. Still, according to the Public Religion Research Institute, evangelical Protestants were the only major religious group as of 2020 that opposed same-sex marriage: just 34 percent of those surveyed support marriage equality.

The country, however, moved on.

“It’s staggering how quickly [marriage] disappeared as an issue,” Balmer said “And so, they almost frantically began looking for something else. And of course, the trans thing was the next thing on the horizon.”

Today, nearly 8 in 10 Americans back nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people, according to a poll from the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute. That includes 65 percent of Republicans. A 2021 poll by PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll found that two-thirds of Americans opposed bills limiting the rights of transgender people.

Still, since 2020, 15 states have passed laws barring transgender kids from playing sports in their lived genders. Three have put laws on the books to prevent trans kids from accessing care for gender dysphoria recommended by major medical associations. Two have outlawed mention of LGBTQ+ history or people for young kids in public schools.

Maps of states that have passed laws that would ban abortion if the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade almost mirror those that have passed anti-trans bans. Eleven of the 15 states with a sports participation ban for trans youth have also moved to curtail abortion rights.

Zein Murib, assistant political professor at Fordham University, says that overlap is no mistake.

“They’re saying, ‘Forget about rights. This is about bodies,’” Murib said. “This is about these bodies being in places where they again presumably do not belong. … You see them deploying scare tactics like, ‘men disguised as women in girls’ restrooms’ or ‘boys in girls’ locker rooms.’”

As 19th News found in an investigation in 2021, the vast majority of anti-transgender bills never use the word “transgender” at all. Lawmakers instead pitch the bills as critical to securing rights for women in sports and larger society. Those arguments fail to acknowledge transgender women, and advocates say they are increasingly out of touch with the general electorate.

Chris Bull is the editorial director of queer media firm Q.Digital and the author of the 2001 book “Perfect Enemies: The Battle Between the Religious Right and the Gay Movement.” Bull argues that Republican lawmakers have abandoned 80 percent of their voters to cater to a sliver of their voters.

“I think that the cliche of American politics is not holding anymore,” he said. “They’re really running base campaigns, that 20 percent of the electorate.”

Still, political scientists warn that the strategy to attack trans rights could backfire and cost them support among an increasingly diverse electorate. More Americans, like Colby, know transgender people than ever before. More than that, evangelicals are statistically shrinking as a voting block, while the number who support LGBTQ+ people continues to rapidly grow.

In the 2018 midterms, the Human Rights Campaign, with polling firm Catalyst, found that people they dubbed “equality voters,” those whose support for LGBTQ+ rights strongly influenced their voting choices, made up 29 percent of the electorate. White evangelicals made up 26 percent of the vote.

In 2020, both groups showed up in greater numbers for the presidential election. Still, White evangelicals made up just 28 percent of the vote, and equality voters had jumped to 37 percent of the electorate.

Geoff Wetrosky, campaign director for the Human Rights Campaign, warned there’s a reason why anti-trans bills still have a foothold.

“Even as they’ve shrunk as part of the population, [White evangelicals] are still showing up to vote in disproportionate numbers, in much higher numbers of their proportion of the population,” he said.

In this, Balmer sees a desperate last gasp. The religious right is shrinking, he says. Younger people are coming out in greater numbers. Youth won’t entertain laws discriminating against their peers the way their parents might have.

“I have real doubts that any legislation is going to be able to sweep back the tide,” Balmer said. “I just don’t think that’s a realistic expectation.”

Older voters are involved, too. Colby and Ashton are part of a national campaign called “Conservatives Against Discrimination” that aims to highlight voices on the right who back LGBTQ+ equality.

Colby still supports candidates who pushed anti-LGBTQ+ bills this year. He likes their economic policies, he said. He thinks those policies will give Ashton the best future. That leaves him in a hard spot at the voting booth, he said. And it leaves Ashton, now 30 and politically moderate himself, navigating complexity, too.

“It’s really human, it’s really challenging because he’s voted for people that I would never vote for,” Ashton said. “But I love my dad, and my dad loves me.”